Since the 2010 Oscars, I thought I’d carved out a fun niche for myself on the internet by subjecting Oscar acceptance speeches to basic word-frequency analyses in search of interesting facts and trends. So imagine my surprise when I found out that Slate has been doing a more sophisticated version of this analysis since 2012 that parses the “thank-you’s” down to specific actors and roles (directors, producers, etc.) I tip my hat to them, although I’m more than a little jealous that I didn’t think of it first, even though I would’ve lacked the resources to have pulled something like that together.

Since the 2010 Oscars, I thought I’d carved out a fun niche for myself on the internet by subjecting Oscar acceptance speeches to basic word-frequency analyses in search of interesting facts and trends. So imagine my surprise when I found out that Slate has been doing a more sophisticated version of this analysis since 2012 that parses the “thank-you’s” down to specific actors and roles (directors, producers, etc.) I tip my hat to them, although I’m more than a little jealous that I didn’t think of it first, even though I would’ve lacked the resources to have pulled something like that together.

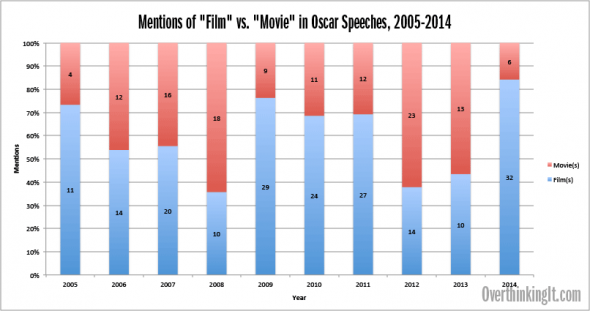

Slate hasn’t blown all of my work out of the water, though. One piece of analysis that I’ve always found most interesting is the prevalence of the term “film” compared to “movie” in Oscar speeches. Here are the latest results, expanded past my original starting year of 2010 to cover a full ten-year span (2005-2014):

When I first noticed the prevalence of “film” over “movie” in 2010-2011, I assumed that you’re more likely to hear the word “film” at the Oscars because it connotes motion pictures of higher artistic quality than that of “movies,” or that this was somehow part of the old guard’s rage against the digital revolution. But I’ve learned from our commenters across the Anglophone world that “movie” is a term that’s rarely used outside of the United States. So when Aussies, Brits, and other non-Americans have a good year at the Oscars, the use of the word “film” is likely to prevail over “movie.”

Was that the case in 2014, when “film” outpaced “movie” by a whopping 32-6 margin? Why, yes. Again, Slate provides the data: Non-Americans outnumbered American winners by a 24-18 margin. I couldn’t find a similar dataset for 2013, but I have the sense that Americans were more represented last year, and if Ben Affleck’s acceptance speech for Argo is any indicator, they preferred to use “movie” over “film,” although it’s not an either-or proposition: Affleck himself used “movie” four times and “film” twice.

By this time next year, I’ll have assembled a Slate-like army of interns to help assemble a massive dataset of Oscar winners, nationality, and their usage of “film” vs. “movie,” but until that time comes, let’s use this occasion to have a discussion about these two tricky words:

AMERICANS: Do you think there is still a meaningful distinction between “movies” versus “films”? A few years ago a US cable TV channel–I want to say TBS or TNT–actually touted the fact that it showed “movies, not films” to let viewers know that they were safely in Adam Sandler “movie” territory. Were they actually on to something?

THE REST OF THE ANGLOPHONE WORLD: Why do you prefer to say “film”? Is the term becoming archaic, given that more movies motion pictures are being shot without film, and almost all are being projected digitally? Do you have some other way of distinguishing popular “movies” versus artistic “films”?

EVERYBODY:

Is it useful or constructive to have a shorthand way of distinguishing between popular cinema versus arthouse cinema? Does that help us apply more appropriate standards to each, or are we creating an artificial separation between the two and excusing the weaknesses of both?

Sound off in the comments!

My only real note is that “movie” itself comes from “moving pictures,” which is likewise a quaint way of looking at things (if more germane than “film” in this era of digitization).

This “motion picture” brought to you by “talkies” – it all sounds so archaic when you really think about the words… or else I’m secretly high as a kite and everything sounds funny.

Should we all go out to the “digies” tonight?

“Hey babe, how about I take you out for dinner and a digital video compression algorithm shown in large format?”

Not adding to the discussion, since I’m no anglophone world – but the term “film” is used not only in variants of English. “Film” means “movie” all over the world, even in those place, where “film” doesn’t mean “thin layer” or “photographic film” etc. (as the wiktionary sums up in translation section: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/film#Noun), while “movie” means “movie” only in American English/Internet. That could be one of the reason the “film” is so persistent – it’s one of those words which became pretty much universal. Half of the world watches “films”, some people watch “kinos” (“kino” means “cinema” in German and the term probably expended on the “films” as well), but the “movies” are just American – so the term “film” is like, more handy?

Besides, half of the dictionary comes from ages ago and its first meanings/association has little to do with its meaning now. That’s the way language works, especially when it comes to names – many nations died during the course of time and the only things left of them are used to this day names of places/rivers/mountains etc.

Tirli,

I don’t think it would be entirely accurate to say that people watch ‘kinos’ in German, which has you’ve said means cinema (i.e. refers to the art itself or, in shorthand, the place where you watch it). The word ‘Film’ is used in German (and also in Russian, where they also refer to cinema as kino).

Some additional comments:

In my native French, we pretty much only use ‘film’ as well, and at least in Quebec, we have not equivalent of ‘movie’. Some people from older generations use ‘vues’ i.e. ‘views’, but that has very much fallen out of use, and even then had no connotation regarding the quality (arthouse vs popular) of the film being referred to.

As to the validity of the movie/film distinction:

I think it’s no surprise that the term movie, used to refer to popular cinema, is used mostly in the US, as after all the US is so much more prone to produce purely commercial cinema, whereas in the rest of the world, there’s a stronger propensity to strike a balance between art and entertainment in their cinema. In such a case, since every offering can/should be judged according to its merits i.e. everything has a certain artistic pretense, there’s no need for a word specifying a purely commercial undertaking.

To sum it up (I’ve had a long day and I’m not thinking straight):

Movie: Purely commercial cinema. Almost exclusively produced in the US where the practice originated, hence why the term is used only there. ‘Closed’ to criticism, since the production is mainly geared to making money and ‘entertaining’, so much so that it becomes almost nauseating and unwatchable (google: Michael Bay).

Film: Made with artistic aspirations even if not always arthouse. ‘Open’ to criticism regarding its artistic and entertainment value, and such productions will usually try to balance these two aspirations to some degree (sucessfully or not). Usual approach to cinema the world over, but also present in the US.

The thing that makes this complex is that native English speakers would use both “movie” and “film” to refer to the same motion pictures. It’s not that there are two categories of motion pictures but more two ways to refer to the same works that have different connotations. There’s nothing incorrect in English about calling Rashomon or The Seventh Seal “great movies.” Likewise, no English speaker would seriously object that the phrase “the second Transformers film” is ungrammatical. Generally–but not always–when an English speaker talks about a film they are talking about it as an artistic work with some seriousness and when they talk about a movie they are focusing on it as an entertainment or pastime. This would be a totally reasonable exchange to have:

“What did you do last night?”

“We went to the movies.”

“Oh, what did you see?”

“That new Almodovar film.”

I should note that in the above I used the term “English speaker” when I meant “American English speaker”. Not familiar enough with other dialects to comment, except that I observed while living in Ireland that “movie” was rarely used there and they used “film” much more, to my American ears.

I don’t disagree that the exchange you described could take place, but then again you *are* speaking of American English speakers, so the casual use of movie shouldn’t be surprising.

Plus (I don’t know if it has anything to do with my being a native francophone) but even I would be more likely to use ‘movie’, especially in a more casual conversation, because the word just rolls off the tongue easier compared to the anglicized version of ‘film’. None of that means that the terms ‘movie’ and ‘film’ don’t have some specific connotations, more that people usually neglect such considerations more often that not (sorry for the underthinking there!).

As an Australian the word movie is also used here a lot more by the lay person then the word film. However you notice the distinction more from the people who are “in the industry”. Reviewers, critics and actors/directors etc do seem to use the word film more. In interviews you will often hear the interviewer say movie and the actor then talk about the film. Its not like I have any empirical proof to back this up but this is just in my experience. As for the reasons why there might be this distinction, I have no idea, anything I could offer would be pure guesswork.

The comments above about how movie is an American term may mean that we really have become more Americanised (funny how spell-check wants it to be “ized”). However most language which has become Americanised is more prevalent in the younger generations while this movie/film distinction appears to be across all generations. Again though, that’s just my unscientific observations.

This has always been the whole of my opinion on the subject:

If “movie” is too lowbrow (or pedestrian, or American) for you, say “film.”

If “film” is too pretentious for you, say “picture.”

If “picture” is too old fashioned, say “movie.”

Just please, whatever you do, never ever call it a “flick.”

Like ThatGuy above, I’d like to chip in that movie is much more common in Australia than film.

The prevalence of film in awards speeches may be due in part to the fact that most Australian/Kiwi/British actors that are accepting awards are predominantly theatre actors who would mark the distinction between a film (more artistic) and a movie (more of a commercial venture).

From a quick search of Australian Academy Award nominations, the 12 Academy Award Nominations given to Australians for acting since 2005 went to 8 actors. Of these 8, all but Heath Ledger have both formal training in acting and careers in the theatre prior to “breaking through” to the US film market.

So I think that the split that you are seeing is not necessarily due to the use of the words movie or film internationally, but the history of the international talent receiving the awards.