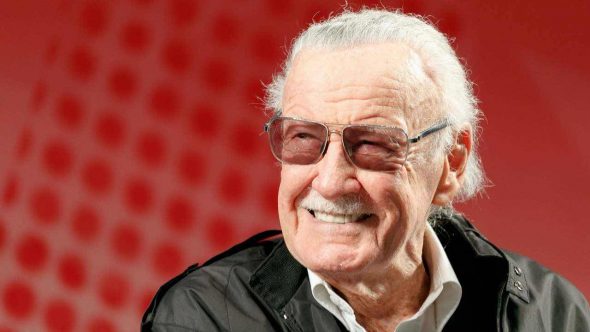

Matthew Belinkie: Stan Lee is, without a doubt, the most famous creator that the world of comic books will probably ever give us. But here’s something interesting about him: almost no one actually reads his work directly anymore. Those 1960 Spider-Man, X-Men, and Iron Man comic books come off as corny as hell to today’s readers.

So he has sort of an interesting position in today’s culture: revered for the characters he created, not the words he actually wrote. Can you guys think of anyone in a similar position, where his body of work is hopelessly dated but adaptations of it are timeless?

READ MORE: Marvel Comics on Overthinking It »

To a much lesser extent, Edgar Rice Burroughs. Tarzan is one of those stories that will always be with us, but the actual dime novel is pretty cheeseball. Maybe Bram Stoker. Dracula has its fans, but I don’t think the novel’s Dracula is anyone’s favorite Dracula.

Peter Fenzel: A big one who comes to mind for me is Gary Gygax, the most famous creator of Dungeons and Dragons. Due to a variety of personal and business conflicts, he was barely part of Dungeons and Dragons after the early 80s, and so many people are familiar with or have played a Dungeons and Dragons game—or a similar tabletop roleplaying game—without playing the Gygax originals. Certainly his Dungeons & Dragons cartoon does not hold up (though the Wayans/Irons movie doesn’t either).

It’s odd. With Magic: the Gathering, Richard Garfield, who created it, periodically comes back and does a set. But Gygax moved on (and now he’s passed on). And while I’m sure his other games are good, none of them holds the cultural cache of Dungeons & Dragons.

Jordan Stokes: Would you accept Gene Roddenberry?

I wonder if this isn’t just generally true: If the characters that you create really stick around, people will end up retelling the story, and eventually your version of the character will be weird and old fashioned.

Is Hans Christian Anderson more famous as the author of “The Little Mermaid,” or as the author of the story that inspired Disney’s The Little Mermaid? Which version of that story is the “real” one?

Peter Pan—the actual J.M. Barrie version of Peter Pan is great, but it’s stranger than you probably remember.

But even if we accept that premise, there’s still something odd and surprising about the case of Stan Lee: People don’t usually live long enough to watch your version of the characters be surpassed and forgotten in real time. Here I would tend to blame the particular pressure-cooker environment of comics publishing.

Arthur Conan Doyle was famously unable to walk away form Sherlock Holmes’s adoring public. What if he hadn’t owned the rights: what if the rights had been held by—well, by Marvel. And official Sherlock Holmes stories just kept getting written and published and sold, right down to the present day? What would we think of Doyle’s original stories?

(Another place that this has absolutely happened: James Bond.)

Matthew Wrather: You could make an argument for George Lucas. OK, yeah, the original Star Wars trilogy is still classic, and is still watched as-is (well, sort of… digital updates and all that), but it’s not the primary Star Wars anymore, at least in the marketplace. (Matt, you yourself wrote an article about the extremely weird irony of your kid interacting mostly with the Clone Wars.)

And it’s an interesting case because we actually have the counterfactual in the prequel trilogy. Episodes 1–3 were not great, but it seems like they actually met George Lucas’s goals — he got what he was after.

But Disney — as they did with Marvel — has managed to extract what thrilling and engaging about the DNA of Star Wars and make some pretty compelling movies out of it, and also Solo.

(Brief aside: Unlike the MCU, which goes from strength to strength, it does seem like it’s proving harder to nail down the formula of Star Wars as a franchise, maybe because the formula is more intricate, and maybe because they are trying to fish the same hole over and over and over. The different main characters in the MCU provide opportunities to play with tone and genre, whereas all the Star Wars movies are some form of heist film.)

So George Lucas: The characters survive, the words fall away (“You can write this stuff, George, but you can’t say it.”)

Stokes: What are the biggest counterexamples? Here I mean:

- A writer is famous for inventing a character that’s still in active use (i.e., new stories are still being written about them), but also…

- People still authentically enjoy the original version?

Jane Austen springs to mind—and yet I’m not sure that (1) applies, because although there’s a hundred adaptations of her books, we didn’t see the greatest rom-com auteurs of the 80s, 90s, and today making fundamentally new stories that just happen to star Lizzie and Darcy and Elinor Dashwood.

James Cameron, maybe? I think the consensus ranking goes T2 > The Terminator > The Sarah Connor Chronicles > doodles of the T–800’s exoskeleton that Mark made in the corner of his Social Studies homework back in high school > Rise of the Machines > irritable bowel syndrome > the rest of the garbage they’ve been foisting on us.

But The Terminator came out in 1984; Lee’s big productive decade was the 1960s. So in terms of datedness, we’re talking about Cheers vs. Gilligan’s Island, here.

Belinkie: Stokes, I’d say the best counterexample is Tolkien. The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are classics that are still widely read today. But it’s also true that the movies (and to a lesser extent the video games) are their own thing. With a huge new Amazon TV series in the works, I think it’s safe to say that Tolkien adaptations and reimaginings will be a thing for a long time to come, but I don’t see them overshadowing the original works.

If I wanted to be a smart aleck I could cite Homer. There’s a universe of adaptations based on his work, but the originals have never gone out of fashion.

Stokes: … do you not want to be a smart aleck?

I wonder, though, because isn’t the current consensus that the Homer of the Iliad is a different guy/team of guys than the Homer of the Odyssey? And although the Iliad was for a long time the more respectable poem, I feel like the only one I knew about growing up was the Odyssey.

I can kind of imagine Homer1 sitting around all disgusted, watching the Odyssey take off, being like “Did you miss the part where Odysseus is kind of a dick?”

“Good Homer nodded, I guess. smdh.”

Fenzel: The counterexample that came to mind for me was Agatha Christie. People still read Murder on the Orient Express. The movie adaptation by Kenneth Branagh was a thing. She has shown up in the new Doctor Who. Despite tons of imitators, there is neither interest in abandoning her work nor making a non-canon Hercule Poirot prequel.

Belinkie: But comic books feel like a unique case. Jerry Siegel and Bob Kane are not nearly as famous as Stan Lee, but they were in a similar position of seeing their signature creations, Superman and Batman, catapaulted to a new level of popularity through the adaptations of later generations.

I’d say this is partially because the stylistic conventions of the golden and silver ages were so different than we’re used to today. But it’s more because all these comic book heroes really leaped into people’s imaginations on the big screen. They didn’t know it at the time, but these comic book writers were basically doing the rough drafts of blockbuster films, made with technology that hadn’t even been invented yet.

Fenzel: “I’ll try moustache waxing! That’s a good trick!”

Stokes: To me, the lack of a non-canon Hercule Poirot prequel disqualifies Agatha Christie, basically for the same reason that I disqualified Jane Austen.

The claim that I’m trying to make is this:

IF you are famous for creating both a setting/character and a story,

AND later writers are still making new stories using your character/setting,

THEN the new stories will eventually become so successful, or so well-adapted to

modern taste, that your original story will be forgotten, so that eventually you will be famous only for creating the setting/character.

Every adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express reinforces the fame of Christie’s story, because it’s Christie’s story.

Every “Hercule Poirot vs El Chapo” fanfic, or whatever, only reinforces the game of Christie’s character.

Belinkie: I don’t know, Stokes. Think about Frankenstein. Sure, it’s been adapted in a thousand ways. But the original book still has a ton of fans! I guess you’re saying that given enough time, Frankenstein the novel becomes a niche thing but Frankenstein the character lives on? And perhaps the only thing that’s unique about Stan Lee’s case is what a short shelf life his original comic books had? (By the way, I mean this not as a criticism of Stan. His comic books did exactly what they were designed to do. He was not aiming to write literature that would stand the test of time – the fact that his characters are still with us, with a large amount of their original origin stories intact, is remarkable.)

Stokes: Yeah, I think the original Frankenstein already is a niche thing. As evidenced by the fact that “Frankenstein” is a mostly non-verbal green monster with neck bolts who is brought to life by electricity, rather than a doctor who brings a highly articulate unnamed monster to life using chemistry. When later properties reference or borrow Frankenstein (as in Mel Brooks, or Van Helsing, or ‘I was a teenaged Frankenstein,’), they borrow the James Whale version.

Belinkie: Okay, that’s an excellent point. But I still think people we’ve talked about like Arthur Conan Doyle, Mary Shelly, Jane Austen, and Agatha Christie are far more read and appreciated today than Stan Lee, even though it’s undeniable that Stan Lee’s characters are an order of magnitude more popular.

Stokes: True.

Belinkie: Part of this is that I get the sense that Stan Lee was really writing for a very young audience (like 10?) whereas the film versions of his characters are darkened and deepened a bit. Marvel’s movies don’t feel like children’s entertainment exactly!

Stokes: Teenager’s entertainment, perhaps, but yeah. And is the same thing true of the current run of X-Men in the comics?

That is interesting though—certainly there are lots of grim and gritty reboots, but it’s hard to think of anything else that’s so successfully made the jump from the children’s section to the mainstream adult section.

(Also interesting that – purely in terms of comics sales – this seems to have been a mistake, because the YA market is huge, and other players are now filling that niche. I doubt Marvel’s hurting for cash these days, though.)

Fenzel: Twain gritty rebooted himself in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. He’s the original Zack Snyder.

Stokes: (Mississippi River flows in s l o o o w motion, then explodes in an eruption of gore and bone fragments.)

Wrather: You guys beat me to it. I was going to bring up books for children as a Stokesean counterexample to the Belinkie Stan Lee Conjecture. One selling point of children’s entertainment is that it demonstrates a continuity in time to the adults who actually buy the children’s entertainment. It’s just like what you enjoyed when you were a kid!

Think about Sesame Street — the idea of the continuity of a neighborhood is built into the show’s DNA. Even the change is conscripted into a narrative of continuity. Jim Henson passes on, but Kermit remains the same. Caroll Spinney retires, but Big Bird remains the same. The humans age and leave the show, new humans come in. There is an organic development built into the concept.

(This doesn’t actually hold about Sesame Street, mostly because it’s supposed to be edifying and our idea of what is edifying has changed so much over the years. Watch episodes from the seventies on streaming: OG Oscar the Grouch was a sociopath; OG Cookie Monster was a straight up drug addict.)

What about The Berenstain Bears? they keep making new ones, yeah? Heck, what about The Simpsons, which has gone through five or six Ship Of Theseus transformations at this point.

There are more extreme examples: The Hardy Boys series was produced in a literary sweatshop from day one, so it was always already an Baudrillardian simulacrum of itself.

For this reason, the contemporary rewrites seem less like a betrayal of the spirit than the continuation of the tradition. My dad used to read me a chapter of a Hardy Boys book before bed—he’d liked them too, as a kid—and one day we decided to be hipsters and read (a reprint of) a first edition. It was straight up racist. Turns out that what to me were the OG Hardy Boys books, the hardcovers with blue spines, were actually rewrites from 1959 aiming mostly to remove the N-word.

I’ll bet there are a lot of interesting examples of character/setting continuity in genre fiction, where there is a tradition of a series of novels featuring the same character — Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe; Lee Child’s Jack Reacher; John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee. And aren’t the late Tom Clancy and the living James Patterson more brands than primarily authors at this point?

Jordan: And there again we dimly see the brutish mitt of capital turning the crank. Robert Ludlum invented a spy named Jason Bourne. Then Robert Ludlum died. But it was lucrative for there to be additional books – and so more books there were.

Fenzel: I feel like I’ve read enough derivative pre-capitalist fan fiction to not attribute the phenomenon to capital. Or, at least, to not attribute the existence of the crank to it, and instead identify it as one of many crank-turners.

There are such things as artisanal, hand-woven brutish mitts. Like how in the gritty Pythagorean reboot Helen of Troy was from the moon.

Wrather: The Aeneid is fanfic. #hottake

Fenzel: Ultimately, though, what turns the crank is desire: we make more of a thing because we want more of that thing, even if the original creator is gone. And just like people are carrying Stan Lee’s work forward, he spent most of his career advancing the ideas of others (not just original superhero folks like Siegel and Shuster or Bob Kane, but also contemporaries like Jack Kirby). This has been going on in comics for as long as there’s been comics.

I think we feel it more, though, right now. When a creator passes on, there was a choice that is gone. It used to be—in principle, at least—that if we wanted Stan Lee’s version of comics, we could go to him, and if we wanted a different version, we could go to someone else. Looking forward, there’s only one way that it can go.

But part of what felt special about Stan Lee is that he seemed so happy to see other people making his characters thrive. He would probably want us not to fixate on current heights, but to use tools, media, and cultural moments beyond even what we have now to take his ideas and our own even further, even higher.

You know, “Excelsior!”