Matt Belinkie: Does anyone have a hot take on why It is breaking records? I’d say it’s the appeal of horror in a scary time, plus nostalgia. This movie being a period piece seems significant.

Matt Wrather: My hot take is going to be all, “WTF do you people like horror movies for?”

Belinkie: Why do people like sad dramas?

Wrather: I only like Gossip Girl, so I’m the wrong person to ask that question.

Belinkie: I’d make an argument that horror is the most inherently artistic genre. It requires every tool of filmmaking to come together – costume, lighting, editing, sound, visual FX, etc.

Richard Rosenbaum: It’s also inherently simple to judge its effectiveness: if it scares you, it succeeded. It’s the converse of comedy: if it made you laugh, it succeeded. These are spontaneous reactions.

But as Wrather points out, obviously we don’t derive the same kind of pleasure from a horror movie as we do from, say, a comedy. Fear is a negative physiological state (or at least a bad-feeling one) that we seem to have evolved to try to avoid.

So I think there are two main draws of the horror genre, and both of them are related to the fragility of human bodies. Horror serves as:

- Memento mori; and

- Vicarious triumph over pain and death.

The memento mori part is obvious; horror movies typically are about the destruction of human bodies and/or minds, in part or whole. A person or group of people are in mortal danger and at least one of the characters dies. The whole thrust of the narrative is dedicated to avoiding death, so it forces the audience to think about death in a much less abstract and more visceral way than most other genres. Most of us go around in denial of death because there’s no other way to live, really. But it’s also healthy to occasionally contemplate suffering and death, and instinctively most of us understand that. Horror allows us to contemplate suffering and death through an entertaining and familiar narrative structure and for a designated, finite period of time, in conditions we can control. Which frees us from having unscheduled existential crises that we might not be prepared for.

The other part of it is the vicarious triumph. Mirror neurons mean that we empathize with people who are having experiences, even fictional ones. Most horror movies bring to the fore the fact that our bodies are physical, subject to damage and decay, and eventual inevitable death. We will suffer and we will die. And we feel terrible for these characters who are experiencing senseless suffering before our eyes. They will all suffer and at least one of them will die.

But we will not die just from watching the movie. Our empathy does not extend to feeling exactly what the characters onscreen are “feeling.” We are realer than they are. This privileged position allows us to withstand a certain proportion of the characters’ distress — and transcend it. The horror fan is a more muted version of the masochist who consensually submits to being harmed in order to prove to herself that she is stronger than pain. (This is something I’ve heard from more than one self-described masochist of my acquaintance.)

So in this way, horror is a kind of Nietzschean crucible. We’ve gone through these tortures and transcended them. And subsequently we are that much more prepared, or… like, inoculated against fear and pain in the future.

Stokes: To play the devil’s advocate, Richard, would you say that a movie like San Andreas offers the same set of pleasures? (Or rather, non-pleasurable but still desirable psychological factors?)

Rosenbaum: I haven’t seen San Andreas, but I think that natural disaster movies do similar things, just on the civilizational level rather than the personal level. Reminding us that our whole society and way of life, which most of the time seem so stable, are actually precarious and, like every other one that’s gone before, will inevitably crumble. But we have lived through the destruction of civilization and even the entire planet so many times already.

I haven’t been interested in a disaster movie for a pretty long time, maybe because that degree of repression that’s necessary on a day-to-day basis to make them effective as an outlet isn’t there for me; i.e. the world around me, quite against my will, is doing a pretty aggressive job of making me hyperaware that The End Of Everything Good is upon us. So I’d rather dive into a videogame to pretend that the world is savable and that I personally can do anything even infinitesimally efficacious toward that goal.

Stokes: That’s interesting: so you’ve successfully repressed the fact that you will die, but you’re finding it hard to repress the fact that we all will die, and this is shaping your media consumption habits. I wonder if the difference between horror fans and non-fans has to do with what we find easy to repress.

I want to keep thinking about the boundaries of the horror genre, though. Wrather, or anyone else who has a big problem with horror: how far does that extend? Do you have the same problem with horror literature that you do with horror movies? How about really old horror movies, stuff like The Bride of Frankenstein, where the scares are so muted by modern standards as to hardly count as scares?

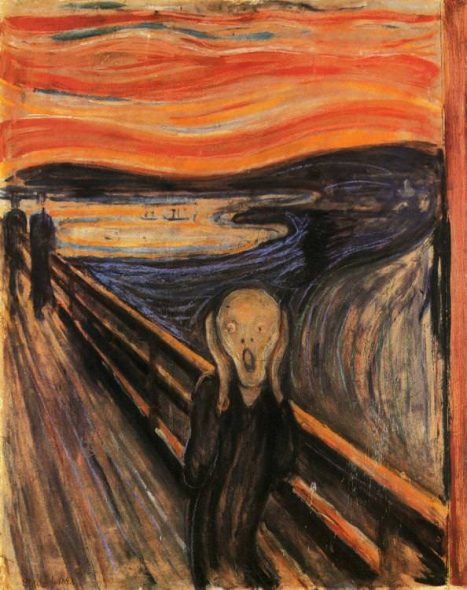

How about this:

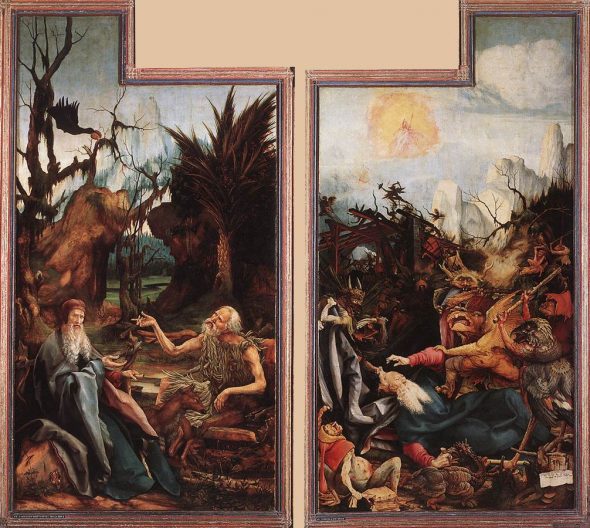

Or how about this:

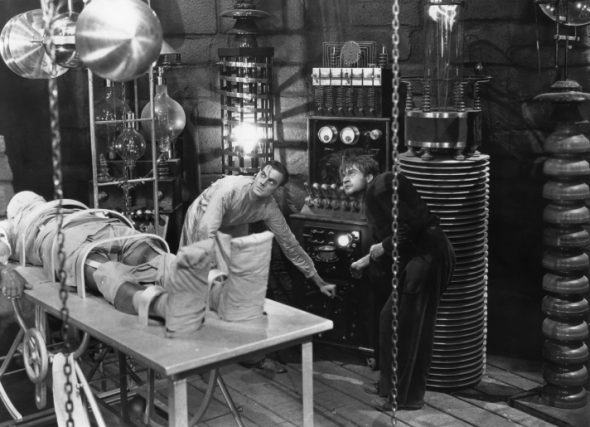

And also this:

Note that these art/religion examples fit pretty well with Richard’s “memento mori” and “triumph over pain” hypotheses. I’m not sure The Bride of Frankenstein would fit, though, and any definition of horror that leaves that out is one I’m not on board with.

Peter Fenzel: I think I might be a bit like Wrather in this. For me, horror produces sensations I do not want, like whiskey, tickling or bubble tea. But slightly different media give me no trouble at all, like tequila, massage or rice pudding. The example that sealed it for me was Blade. I was okay with Blade. Blade made me feel good. But I still wince and feel bad remembering Critters 2.

I do not like that carving of the woman pulling thorns through her tongue. It is not welcome.

But I locate my objection in the sensation. Richard has located his hypothesis in the morals. And of course in horror the two – sensation and morals – seem entwined.

So I guess I’m asking is horror a moral genre served by sensation, or a sensual genre served by morality?

Rosenbaum: Pete, I think it has to be the former. Horror is a moral genre served by sensation. If your primary concern is seeking what feels good and avoiding what feels bad, you’re not going to be interested in horror. The evolutionary function of fear is to make you run away from things that could be harmful. That’s why it feels bad. But if the moral concerns are primary, then we’re willing to endure the negative affect and thereby transcend it. If it were primarily sensual I don’t think the horror genre could even exist.

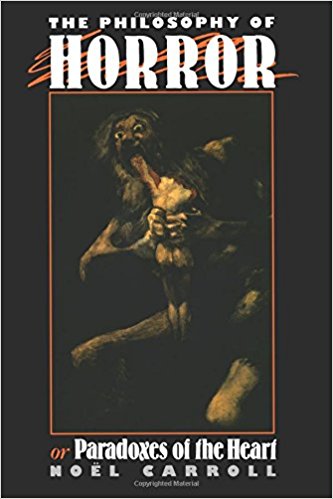

Stokes: There’s a philosopher, Noël Carroll, who has a whole book dedicated primarily to the question of why people should seek out scary experiences. His basic answer is that there’s a distinct emotion, “art-horror,” which is qualitatively different from actual horror. The first is pleasurable, the second, not.

There are some interesting shades to this analysis. Surely the difference is just that we know that horror monsters can’t really hurt us? But no: if you’re the kind of person that’s afraid of heights, you will be terrified by walking up to the edge of the Grand Canyon, even if there’s a chest-high fence. You rationally know that the drop can’t really hurt you — but that feeling is real horror, not art-horror.

I wonder, though, whether Pete and Matt just don’t feel that difference? (Obviously they know the difference, but as Carroll points out, knowledge isn’t the nature of the difference.)

Rosenbaum: Ooh, that is interesting. I wonder how plausible it is, though. Why would there be an emotion “art-horror” that has this particular relationship to real horror, without any analagous adjuncts for other emotions? ARE there emotions analagous to art-horror for other emotions? The only thing that comes to mind as a possibility is maybe “art-lust.” The sexual arousal you feel when watching something that you know you would not be remotely interested in experiencing in real life.

Stokes: It’s been a while, but I’m pretty sure he floats the idea that we should expect to encounter art-sadness, art-boredom, etc.

Rosenbaum: “Art-sadness”? Certainly we sometimes like to experience sad art. But then, there are some songs and movies that make me feel SO sad that I can’t deal with them. For instance, Requiem For A Dream is the best movie I’ve ever watched that I never want to see again. So if there is some distinction between art-sadness and actual sadness, Requiem seems to have overrun it. Yet I wouldn’t be able to call that film a failure because it made me real sad rather than art-sad.

This is a very interesting concept. David Foster Wallace (pbuh) seems to have been working on trying to evoke something like what I guess Carroll would call art-boredom in his final, unfinished, novel, The Pale King. It’s about people working at the IRS.

Stokes: I get what you’re saying, but I don’t think it works as a counterargument. Yeah, Requiem For a Dream isn’t a failure — but if there was a whole genre of movies that reliably made you sad in that way, you wouldn’t watch them. Right? So it’s still plausible that sad movies in general are meant to create art-sadness (and that that’s what people seek them out for). If Requiem manages to push right through to actual sadness, we can give it a round of applause. But we should recognize it as an exceptional case. Maybe the better question is this: when a movie that makes you just a little bit sad, is that emotion just a weak version of regular sadness? Or is it something slightly different? If art-sadness makes sense as a concept, that’s where we’d find it.

Also, Requiem for a dream is, like, not NOT a horror film? Just saying, is all.

But returning to horror specifically: I still want to know whether the horror-haters are as bothered by “The Tell Tale Heart” as they are by It. If “swimming in cortisol for an hour and a half” is the problem, are you also bothered by Die Hard? For that matter, are you fine with Tales from the Crypt? Because each of those was less than thirty minutes.

The reason I keep harping on this is that, on the podcast, Wrather said that he was fine with roller coasters. This fascinates me! I find roller coasters much more scary than horror movies. I mean, I like them both, but if I were cortisol-averse it’d be roller coasters that I’d shy away from.

Similarly, I wonder if maybe the sensation that Pete is so bothered by might be something other than actual fear. Or maybe the sensation is fear, but the aversion doesn’t arise from the sensation alone. Maybe it’s fear + (some other factor) that does the trick.

Rosenbaum: While you’re in slightly more real physical danger on a rollercoaster than at a horror movie, rollercoasters only give you like 1/60th the time to contemplate mortality.

Stokes: And this turns us back to the question of whether horror is a moral or a sensational genre. To my mind, morality and sensation in horror are put into a mutually reinforcing feedback loop.

Initiate the morality-sensation feedback loop!

The moral content of horror is itself often horrific. Take the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street series, for instance, where so often the message is that the wages of sin (specifically sex) is death (specifically getting machete- and/or glove-murdered). This is a disquieting message. Even if you reduce it down to the bare bones moral, it still provokes a sensational twinge. That twinge I think is part of what makes it horror (as opposed to some other kind of morality play).

On the other hand, after school specials often have similar morals to this — often the exact same moral, in fact! And these don’t feel horrific, because the sensations that they traffic in are not apt for horror. (They live in more of a melodrama space, typically. Which is similar but not the same.)

And I don’t think that it’s pushing things at all to suggest that part of what makes horror-sensations horrific is their ideological freight. You ought to feel, when watching a horror film, like these are not things that you ought to feel. I suppose a true sadist might watch Friday the 13th and just crow with glee every time someone got stabbed. “Yeah! Eat arrow, Kevin Bacon!” But that response is utterly alien to me. I do thrill to the kills, sort of, but there’s a big part of me that doesn’t. “Horrified fascination” is a phrase that exists for a reason. This response gets bounced around and mediated between fan communities and different layers of the psyche. So if you’re watching with a fellow horror fan, you might well say something like, “Oh, Kevin Bacon’s about to get it! Woo!” But I don’t think anyone is actually THAT desensitized.

There’s a joy in sharing the transgressive space with another fan, and the kinds of things we say about horror are often celebrations of that joy — but the space remains transgressive.

Rosenbaum: Interesting. By that metric, Lolita might be classified as a horror novel. Because it’s so well-written it gets us to empathize with a complete monster, which undermines our own sense of the objectivity of our personal moral structure.

Stokes: Or at least it might be horror-adjacent, like the after-school specials. I’m also fine with saying that it can’t be horror without being notionally scary — having to do with violence and death and monsters and whatnot. It might well be that the feedback loop I’ve described applies to many other genres. I’m just trying to separate horror from other types of recreational fear, like thrillers, roller coasters, and so on.

Rosenbaum: Agreed. I still stand by the idea that the focus of that scariness tends to be calling attention to the physicality of the body. Even “spiritual” horror movies like The Exorcist, which are more about danger to souls, very heavily rely on bodies going wrong for its horror content.

Ben Adams: One element of horror film that I think we’ve left out of the conversation so far is the importance of mystery – the vast majority of horror movies have some form of puzzle to some it shocking backstory to reveal. (E.g. where did the little girl in the well come from? What is the Babadook? Why is Jason so angry?)

A lot off the elements discussed above – body horror, jump scares, etc. – don’t require this kind of mystery. You could in theory have a movie with those things where the motive and backstory of the monster is laid out right in the beginning.

But it just doesn’t work. Why is that?

Stokes: Does it not? I don’t think there’s much of a mystery to, say, Jaws. Maybe on a meta level: which of the characters will the shark eat next?

I see what you’re saying, though, and it’s true that horror without a mystery feels weirder than, say, comedy without mystery. And there are sometimes — often — these scenes of horrific unveiling…

… which seem to plug in to the same kind of impulse.

Part of it might be that ALL narratives are sort of laid out as mysteries. There’s always some kind of territory to explore, or puzzle to solve. And very often this is mapped onto the human body. Hey, a birthmark! You’re the Prince of Ruritania! Hey, a fleur-de-lis tattoo! You’re Athos’s wife! Hey, a sixth finger! My name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father, now prepare to die! (I’m getting this from Peter Brooks’s Body Work, by the way, which is a lot of fun if you’re in a lit crit kind of mood.)

Horror uses this narrative framework — but not always in an obvious way. In older horror films, and in glossy prestige productions today, there is typically a well-formed narrative in which characters take actions to uncover secrets and solve puzzles. These, I would say, play the game of narrative straight. But there’s another kind of horror movie — films on the order of Critters 2, the cheap, grotty, nasty stuff — where it seems to operate subliminally. On the most abstract level, there’s stuff like Hostel 2 where they eventually break the film down into a kind of haunted-house-tour-slash-powerpoint-presentation: here’s the nasty thing in this room, here’s the nasty thing in THIS room, etc. etc. ad-literal-nauseam.

I think Brooks would say that even the most refined kind of narrative is just a sublimation of the basic impulse to see the nasty thing in this next room. Making The Remembrance of Things Past the poppyseed bagel to Hostel 2’s brick of uncut heroin.

“La maladie est le plus écouté des médecins: à la bonté, au savoir on ne fait que promettre; on obéit à la souffrance.”

And to pull it back to Richard’s initial theory: well, yeah! Memento mori. We keep the nastiest thing in the nextest of rooms, and its name is called Death.

A simpler answer is that we just like the process of intensely feeling stuff, and we use art as a safe means of triggering a range of feelings. Sure, not all the feelings are as straightforwardly positive as laughter and sexual arousal, but we might just be wired to seek all kinds of arousal. For example, I’m not scared at all by rollercoasters, but I know people who are, and I think they get more out of the experience because the feelings they experience are just more intense than mine.

I know some people think that horror is cathartic, and it may help temporarily drain off a psychological buildup of actual terror. This would predict that in objectively scarier times, there is more need for horror in art. My theory predicts the opposite: When we feel physically safest is when we most crave the art that makes us feel fear, because we crave intense feeling diversity.

I like this answer. Perhaps, continuing the long history of multi-dimensional plots on this site, we could have a two-dimensional space (actually, just the positive quadrant) of artistic experiences. One dimension is the amount of pain or fear, the other is the amount of pleasure. There are lots of ways to combine these two variables to get an intense experience; how much you enjoy a piece of art will depend on how much overall intensity you want, as well as how the two individual variables affect you.

I don’t think the idea that horror creates a physical sensation we don’t like stands up to much scrutiny – it’s true for some people, sure, but e.g. the fine line between anticipation/excitement and nervousness is an often-mentioned phenomenon. Think of roller coasters.

I was thinking much the same thing. I don’t find roller coasters scary – I find them fun, and exhilarating. I do, however, find the long line prior to the coaster terrifying – or occasionally the very slow ascension prior to a drop.

Likewise, the tensest, scariest parts of horror movies for me are the long-drawn out shots where someone’s walking down a hallway or through a dark room, waiting for something to happen. The actual “horrific” content – someone being tortured, or murdered – can be discomforting, or gross, or even comical if done poorly, but for me, at least, is rarely scary.

In response to the first question: “Why is ‘It’ breaking records?” I say the film is successful because is based on one of the most successful books written by the one of the most successful authors of all time. A previous mini-series adaption was also fairly successful and popular. A recent popular Netflix series borrowed the tone and plot points from the book and even borrowed one of the actors for the new film.

That’s a reductive answer that only explains the film’s success. It doesn’t really explain why people liked “It” or any other horror story in the first place.

Maybe it is a metaphorical exorcism. We all have fears, some are subconscious. Seeing these fears on screen brings them to the surface where they can be purged.

The opposite is even true in comedy. If its a good joke people will laugh, but the more we hear the joke the less funny it is. The joke loses its power. If a horror movie is scary, people scream but the more they see a certain horror, the less scary it is.

I think Richard is right. Its about overcoming fear.

I can’t believe you used a food based analogy involving Remembrance of Things Past and used a food item that wasn’t a madeleine cookie dunked in tea.

I’m not too in touch with the current box office, but could it just be that It is breaking records because people really want to go to the movies right now and for whatever reason It’s competition is weak? (Sidenote: I experienced existential dread trying to figure out whether to apostrophize It’s.)

As with so many things in life, the answer lies, of course, in the Evil Dead trilogy.

Because remember, all of these films are basically good. And they are all about the same protagonist (basically) fighting the same antagonists (basically). But they can shift from horror to horror-comedy to straight-up period piece adventure film because the core of all good drama remains intact throughout: an understandable viewpoint character in a plainly explained dilemma, most likely struggling against an overwhelming (and possibly unknowable) force.

The trickier part is balancing this against the core of all good fantasy: a heroic figure who represents the audience while also being more capable than the audience.

Every single artistic work ever created fits on a spectrum between these two points: drama and fantasy.

Evil Dead can shift and defy genres for the same reason that slasher movies of the 80s can glorify their villains in ways that are not always comfortable. Because you can make Ash either more dramatic or more fantastic in the same way that you can to Jason Voorhees (depending on how much of the “protagon-ism” you’re willing to share with them, this rule applying to viewpoint characters only — not to be confused with characters whom we see through the literal eyes of, in which case Jason would be the most prolific film hero of all time).

You can do the same to really any character. Or any person. It’s how propaganda works, too.

So if we’re actually asking the question of “why horror?” then I think we need to get away entirely from things like plot and setting and even all of the character stuff I just spent a few paragraphs on. Because that’s all just the same struggle with different set dressing.

Which leaves us with tone. Something you can change entirely in a scene by just holding the camera on an actor’s face for two seconds longer than usual. We’re talking about discomfort and unease. And you don’t need blood and gore for that. You don’t even need danger. Watch how an infant responds to just seeing another human being not reacting to them for a while: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=apzXGEbZht0

This is why David Lynch works even when nothing actually dangerous is on the screen but Sharknado doesn’t scare you even when friggin’ tornadoes full of sharks are descending on everyone.

This is why I think you can throw any theories about catharsis or conquering violence by restraining it to a movie screen out the window. The gore is splashy but it’s also sometimes distracting. It’s there for the same reason that prat falls are in comedies: done correctly, they work to evoke the emotion that the artist is trying to create. But you can laugh at gore and you can feel just awful watching someone fall down and hit their head on the ground.

So, if that’s all true, then horror movies (and I mean the really messed up ones that get under your skin here; the kind I assume we’re talking about from the descriptions above) are a lot closer to eating ridiculously hot peppers than they are to traditional fantasy narratives. Some people do it to show off, sure, but there’re also a lot of people who are riding the endorphins. They genuinely feel pleasure from certain kinds of pain. And if that’s true then maybe there’s some pleasure to be taken from feeling unsettled as well. I wouldn’t call it catharsis because it’s not a release.

But there might just be something very enjoyable about our own misery. Maybe that’s why we keep encouraging it?

I think what the article and many of the commenters are talking about, but never quite explicitly say is that horror movies aren’t scary, they’re tense, and thrilling. I like horror movies, but I’ve rarely felt afraid while watching them. I’ve been startled by jump cuts. I’ve felt a deep awfulness at watching people suffering (this one less so, since I avoid movies where this seems to be the appeal). I’ve even been unsettled and creeped and made slightly paranoid, to the point where I don’t really want alone. But I’ve never had that bone deep, wide-eye, fear that freezes your muscles as the lizard part of your brain lights up like a christmas tree as it reacts to something that might kill and eat you.

Three Act Destructure’s point is spot on. But I would add that much of that tension is drawn not just from tone, but expectations. A story as an example: I watched Boyhood three times in a theater with an audience (Spoilers for a 3 year old movie with no real plot or twists!). There’s a scene where a bunch of teenage boys are throwing a circular saw blade into a piece of wood. Every single time I saw it, you could hear audiences breathe in and tense up as they waited for the inevitable horrific accident. I did. My friends who saw it with me did. But it never happens. Because this isn’t a horror movie, it’s a movie about a kid growing up and acting like a kid along the way. But because we’re watching a *movie* we expect *something* to happen. And this potentially dangerous situation raises expectations for something bad and unpleasant to happen.

In a horror movie, the dangers are firmly established and bad things will eventually happen. But a horror movie would be bad if those bad things happened too quickly or matched perfectly to the expectations it sets up for the audience. A great horror director will play on an audience’s expectations and the tensions they cause like an instrument. They will some times raise it by having long shots of people walking, or focusing on seemingly benign things, etc. Sometimes they will deflate it by changing the tone. Sometimes they’ll subvert it and release it. The noise being a cat, being one cliched way of doing it. Then, at the appropriate moment, the expectation will be fulfilled. And the how and particulars of the fulfillment of the expectations is another set of notes the movie can play.

How this tension is manipulates. How it’s escalated, deflated, prolonged, subverted, release etc. is what’s pleasurable about a horror movie. It’s also, I think, what separates good horror movie from a bad one.

Additionally, in a horror movie where at least one non-monster person survives or ate least takes out the monster with them, we also get a vicarious feeling of triumph over death. Above you mention this, but only in light of “facing” death in a safe space and being inoculated against it in a way. I would say it’s more like a vicarious wrestling match with death. The monsters in horror movies are, almost by definition, personifications of death. And we watch them kill almost everyone, just like death will one day claim everyone. But then, after the expectations have been fulfilled and the tensions have had their cathartic releases, the Final Girl kills the monster. She beats death. And this is in the third act, when there’s few enough characters that we can identify with them. So, at the end of a Final Girl style slasher movie, the audience also gets a feeling of triumph. Through her, we not only face, but fight death itself and win.

…for now…

That tension is a really good point and I think that horror, like most genres, has a lot of different pivot points for attracting its audience and catering to their desires.

I think a solid non-horror example of this same kind of range in genre (just by way of explanation) is the response that the Winding Refn film Driver had from some disgruntled Fast and Furious fans. They saw cars, they saw heisting, they saw action beats in the trailer and they were expecting a different kind of movie. Which is interesting because Driver IS an action film. It’s an older kind of action film but if you were walk down a Blockbuster aisle in 2017 then I guarantee you that that’s the section it would be filed under.

So okay, horror can be many things. It’s malleable. Speaking of which, the Final Girl. What do we all think of films that end on downer notes or ambiguous endings? Or even final jump scares that are meant to get at the audience when they’re supposedly most vulnerable but which can also have the effect of rendering the narrative arc of the film inert. Who cares if Susie McSurvivalist tricks the monster and releases the ancient curse if she just gets her head lopped off seven minutes later when she’s canoodling with her boyfriend?

Friday the 13th Part 2 even begins with the heroine of the first film being murdered by a spontaneously all-grown-up Jason Voorhees, potentially implying that ALL of the surviving heroes of the other movies are eventually tracked down and killed.

Huh. Maybe that’s why Tommy Jarvis dug up his grave, harpooned his corpse and accidental-Frankensteined him at the beginning of Part 6.

Yeah, Drive is a great example of using and subverting the expectations of its audience. And, I also saw this in theaters with people and got a very clear sense of how people reacted to their expectations

(Spoilers for Drive)

Besides the kind of meta subversion of expectations for a F&F style car action movie, there is also a kind of internal subversion of expectations that had a big impact on the audience. The beginning of the movie does a good job of setting up a deliberate and slightly detached rhythm, style and tone to its action. But there are a couple of moments, where the action turns suddenly and explosively violent. And audiences reacted strongly. The one I remember most is when Christina Hendrix gets shot. If I remember right, almost nothing in that scene hints at something like that before it happens. I remember gasps in the theater. I also believe I remember a similar reaction when Ryan Gosling, without any prelude or warning, starts beating the crap out of a guy in the elevator.

In a way the reactions this movie elicits are the opposite of the ones in a horror movie. A horror movie sets up the expectation and tension of waiting for something bad to happen. Then it uses the fulfillment or subversion of that expectation to elicit its response. Drive, in that opening scene, sets up the expectation of a kind of different kind of tension. More of a cat and mouse, outsmarting the cops kind of deal. The explosions of violence that seem to come out of nowhere at first, thought their frequency increases as the movies progresses are shocking. And, I think most importantly aren’t “fun,” like the explosions of violence in a horror movie often can be. One theory is that by coming out of nowhere, they are truer to violence in real life, which are usually not preceded by any kind of warning. In Drive, like in many action movies, the violence is supposed to feel violent. We’re supposed to feel it viscerally, not in a an abstractly “thrilling,” or “scary” or even “fun” way. In a horror movie, where the audience uses an obviously fictional set of circumstances to vicariously live and feel and struggle through emotions and even metaphoric struggles that are almost impossible to go through in real life. In an action movie where the violence feels closer to real violence, we don’t have the necessary distance to do go through those things.

I was going to mention the last minute jump scare, main character kill, etc., but thought I had already gone on way too long. It’s why I added the “…for now..” ( though I couldn’t figure out the format to make it look right).

To me, any way, these moments always feel very meta. It’s partly because, like you said, they often undo or reverse the narrative. But also because they often come in a way that makes them feel aimed at the audience rather than at anyone in the movie. They are often done in a way where we think the movie’s already ended, after it’s cut to black, or the credit have rolled or something like that. Sometimes it’s just as lame as a “[monster] will return” title card.

In my reading, which follows how I read the Final Girl narrative as a vicarious and symbolic triumph over death, these last little bits serve as a reminder to the audience that these victories are always temporary. After all, if you’re enemy is death itself, every victory is temporary. The movies, or its auteur, feel like they have to remind you of this. The way they choose to do it, in my estimation, depends on how much it wants to reprimand its audience for believing in that victory over death. For example, if it just wants a simple “this isn’t really over” message it might show that the monster is still alive. If it wants to say “dude, this is a movie, and you just watched a bunch of people being brutally murdered and now you’re happy and reveling in triumph?,” then it brutally murders its main character. The movie that most immediately comes to my mind right now that does this is Drag Me To Hell. Where they give the character a super happy, satisfying ending before being literally dragged to hell. I can’t speak specifically to the fates of the characters you’re mentioning though, since I’m not super well versed in the Fridays the 13th. I’ve always been more of a Nightmares on Elm Street kind of guy. Though it is interesting that that franchise has a built in kind of “safe space” after a certain age, since Freddy goes mostly after teenagers. And even that is negated later in Dream Warriors when a grown up Nancy tries to help other children battle Freddy. And it’s subverted and played with on a meta level in New Nightmare when the monster not only doesn’t just kill teenagers, but jumps through the barriers between fiction and reality and hunts the adults who helped create the story.

Anyway, this all goes to my point that the killing the Final Girl is a meta commentary about how no one should ever believe themselves safe from death.