I.

If I’ve spoken to you about television at any point in the last two months, I’ve raved about Amazon’s Patriot. But – if you followed up with, “what’s it about?” – I probably struggled a little.

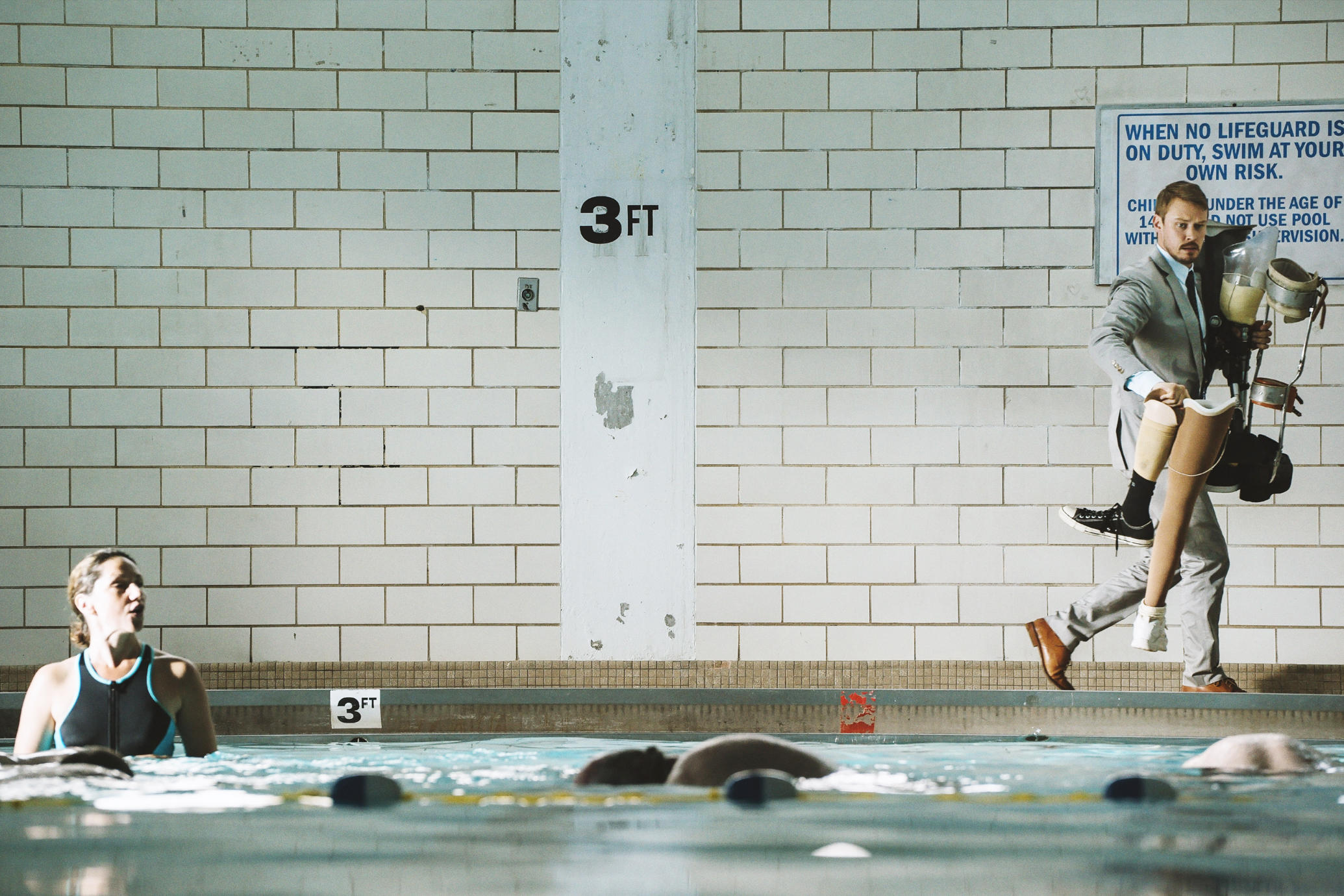

The no-frills plot summary: Patriot is an dark comedy about John Tavner (played by Michael Dorman), a deep cover CIA asset who’s brought back into the cold by his father (Lost‘s Terry O’Quinn), a State Department official. He’s given the task of posing as an engineering executive for an industrial pipe-laying firm. This is the first step in what should be a fairly simple plan to delay Iran’s ability to develop nuclear weapons. But a series of miscommunications and mishaps result in Tavner ducking a murder charge in Amsterdam, hiding from his former folk songwriting partner, and robbing several disabled cops of their prosthetics. And that’s just the first few episodes.

Or:

Patriot is an existentialist comedy in the vein of Curb Your Enthusiasm or FX’s Fargo. Things go wrong, constantly, but in the most plausible ways. No one’s particularly evil or particularly incompetent. They’re all creatures of appetite, like John’s doofy brother Ed (Orange is the New Black‘s Michael Chernus) or his reluctant confidant Dennis (Chris Conrad). They commit to ridiculous plans – like solving arguments with rock-paper-scissors – and those plans work until, spectacularly, they don’t. Patriot‘s genius is in setting these uni-directional vectors up on opposite ends of a plane and letting the tension build as they threaten to intersect.

Or:

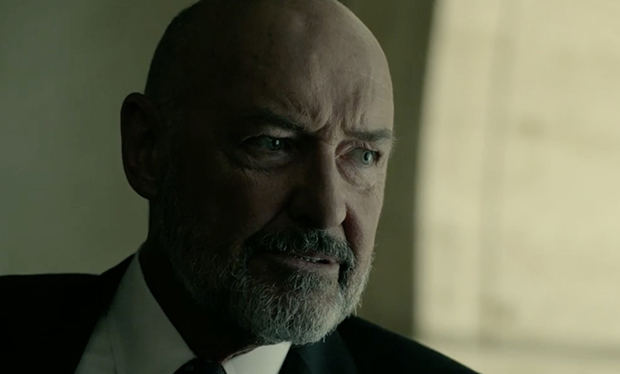

Patriot is a low-key allegory about American imperialism abroad. Viewers get occasional context from John’s father, Tom Tavner (Terry O’Quinn), speaking directly to the viewer in what we gather is a debrief or a deposition. The goal of his off-the-books mission was to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear capacity by bribing a key Iranian official. However, misadventure resulted in that money being handed to Iran’s ruling party, thereby accelerating their nuclear weapons program. Tom, a grizzled Uncle Sam, repeatedly asks his sons to put their health and sanity at risk in order to repair his mistakes. He promises his sons various things – Interpol will never grant that Amsterdam detective permission to interview you; of course I can get you a chair for your apartment – that he is unable to deliver. He’s never angry, occasionally disappointed, and always in need of help.

Or:

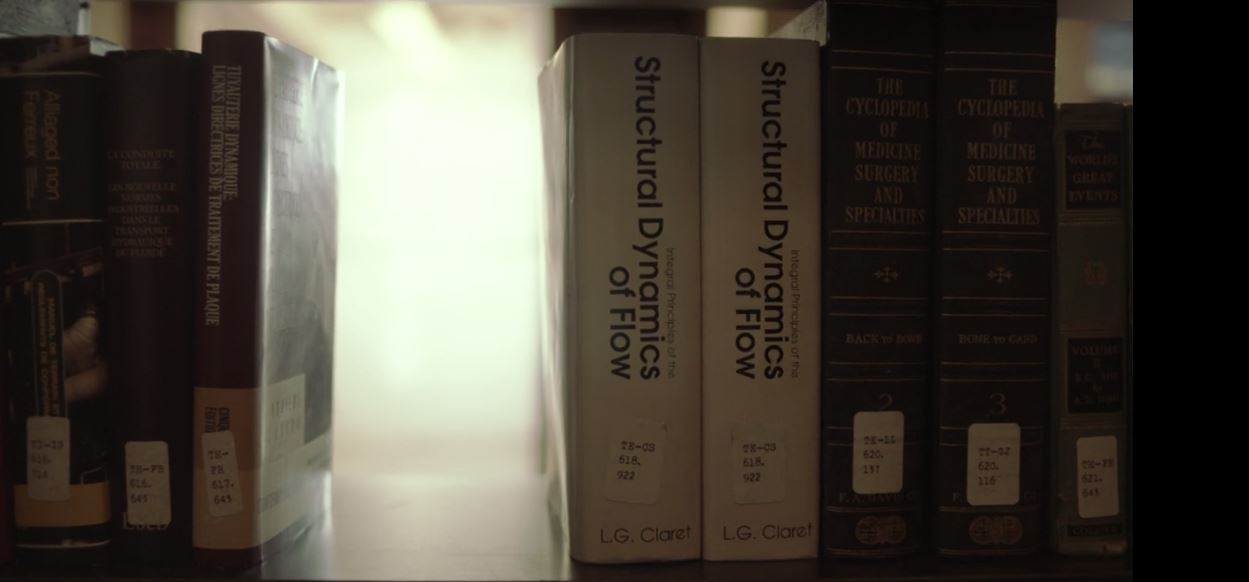

Patriot is a nihilist commentary on the futility of human endeavor itself. Late in E6, “The Structural Dynamics of Flow,” Detective Agathe Albans (Aliette Opheim) interviews the CEO of John’s firm, Lawrence Lacroix (Gil Bellows). When she asks him what exactly his company does, he gives an unusually philosophical answer:

We consult concerning the obstacles, challenges, and insecurities that come up against the simple act of delivering an element from one place to another. To name a few: attrition, gravity, mischief, calamity, incompetence … also, erosion, contraction, expansion, buffoonery.

Essentially, we exist because of the tremendous difficulty inherent in simply transporting any entity from A to B.

That subject recurs throughout the series – the difficulty of getting one object, or any two people, exactly where they need to be. It’s a world full of opponents but no villains, where everyone has the best intentions in the world but irresistible reasons not to cooperate. John makes an ass of himself to his boss, Leslie Claret (Kurtwood Smith), over and over again. It’s never intentional, even when John stands Leslie up for an exorbitant breakfast. It’s just that John’s trying to avoid the Amsterdam police, keep an eye on the Iranians, avoid a family of Brazilian grapplers who want to rob, extort, or kill him, recover a duffel bag full of money, and stay friendly with the guy he recorded an album with (Sons of Anarchy‘s Rob Saperstein). He’s got a lot on his plate!

As the above may suggest, Patriot is a lot of things at once! It’s densely layered, terribly awkward, and bleak in its humor. I have a hard time describing what captivated me about it because of its richness. It’s not perfect – what of this liminal world is? – but it dares more and achieves more than most shows. But it’s very heavy, and a little slow, and it asks you to tolerate a great deal of ambiguity.

Patriot isn’t for everyone. In fact, it might not be for anyone except me.

II.

A few years ago I worked for a tech startup.

The integration of social media, network technology, and venture capital into every part of our lives has made the name “tech company” sort of meaningless. Everything is a tech company. But the one thing most tech startups have in common, regardless of industry, is the need to lean on labor. Labor is the only resource that bends, rather than breaks, when you lean on it. You can’t plead with a building to get larger; you can’t throw a rally to convince the lights to stay on longer; you can’t make eighty thousand lines of code compile in eighty seconds. But you can always ask the new guy to stay late.

My job involved managing ad campaigns for a variety of clients. I had some experience in media planning before I took the job. But when you buy ads as a tech startup, you have to use the startup’s platform to do it. If you can just pick up the phone and talk to a rep at Washington Post or use the self-serve platform at Google, then where’s the added value in your shiny new interface?

It’s a crowded field.

But, of course, if the platform worked exactly the way it should, the company wouldn’t be a startup – it would have a proven product, a defined market, and a business plan resistant to pivoting. Until such time, everything is negotiable. And until such time, things never work quite the way they should. I spent many evenings in the office long after sundown, coordinating with our engineers to try and get a campaign to launch the way we wanted it to. We updated each other via Skype with grim gallows humor – nope, the budgets are 10x what they should be and the end date is before the start date; please scrap and try again.

While the creative team controls the look of a campaign, and the engineers control how the software functions, and the sales team controls whether a campaign happens at all, the media planner – yours truly – controls the money. And in most agencies – and technically, in buying ads for a client, we acted as their agent – we paid for media out of pocket and then invoiced the client. When creative screws up, it’s embarrassing. When the media planner screws up, it can jeopardize the company.

I started coming to work in a state of high alertness, certain that I’d overlooked something and equally certain that I had no idea what it was, waiting for the unexpected email to clue me into a mistake. I learned how easily someone can sit in an open plan office, surrounded by colleagues, and mask a panic attack. I learned how to draft emails while my hands were shaking, how to make it to meetings on time while my legs were numb, how to keep my face neutral until I learned whether I was about to get yelled at or pep talked.

The tide never slackened. There weren’t any wins to celebrate, because we always fought on multiple fronts. There was always the next client who needed a pitch deck, the next bug that needed addressing, the next report whose terrible numbers needed an explanation. I don’t think I made it to a single holiday party on time, even when people came around my desk to remind me that “the work would still be there tomorrow.” I never understood how to respond.

My only consolation, at the end of the day, was that I hadn’t made any mistakes big enough to get fired over. And then they started threatening to fire me.

III.

As part of his assignment, John has to infiltrate an engineering firm, Macmillan. His father, in an early scene with another government official, speaks of John as having “NOC [non-official cover] time in engineering covers.” But we almost never see it. From the beginning, John is given a series of tasks that his resume should prove him qualified for. Every time, he responds with a blank stare and a lame excuse.

As John’s boss, Kurtwood Smith brings to bear all of the patriarchal disdain for screw-ups that a generation of viewers associate him with. He stares John down with blistering contempt. He lectures him pedantically. He sneers at him.

And he’s not wrong to do so! He doesn’t know John is a spy. He doesn’t know John is being extorted by a security guard who’s seen through his cover. He doesn’t know John is the lead suspect in a murder investigation in Amsterdam. He doesn’t know John is only staying at this company long enough to hand off some cash to an Iranian dissident, nor that John needs to retrieve that cash once it falls into the wrong hands.

On the surface, John looks like an industrial engineer – fully qualified for the job he’s been hired to do. Leslie’s frustration with him is reasonable. John’s inability to respond to it with anything other than empty promises is justly infuriating. And yet, against all odds, John is the hero here – because we know about everything else John is going through. We know that there’s a vast conspiracy keeping John from being good at his job. He wants to make his boss happy, but he can’t, and he can’t explain why.

Patriot is the story of a man named John in his mid-thirties – scruffy hair, notional beard, sad eyes – who is trapped in a job that he can’t do and he can’t quit.

IV.

An unspoken tenet of criticism is that you want to connect a work to some universal element, something that a broad audience can relate to. Thematic critiques talk about the underlying ideas that everyone has experience with: love, fear, the desire for justice, the threat of loneliness. Postmodern critiques break down a unique work into a semantic framework that can be understood by academics, even if they haven’t consumed the work itself. Ideological critiques argue that a work contributes to or damages an ongoing social struggle.

In all cases, the critic is a bullhorn, amplifying the work outward. This isn’t just a story, they say, or just a dance recital, or just a painting. This isn’t just the sum of its runtime or the names in its cast. This is something more.

But one of the insights of the great existentialist works of the last century – to say nothing of existentialist comedies like FX’s Fargo and Amazon’s Patriot – is that meaning can be found in anything. Meaning doesn’t need to be universal. Sometimes meaning emerges from accident.

In Patriot, John’s brother Ed forms an unlikely friendship with the brother of an Iranian spy. John’s wife Alice mentions something in passing to his colleague Dennis that turns around his failing marriage, his budding health issues, and his distrust of John. The show’s few antagonists – Leslie, the blackmailing security guard, the looming Peter Icabod – have backstories that make their behavior more quirky than menacing. And much of the great mystery in Amsterdam centers around the chance encounters of a puppeteer.

A work of art can mean something greater than itself. But it can also mean something narrower than itself. Maybe Patriot isn’t for everybody. Maybe Patriot has a target audience of exactly one person.

Of course that’s not true in the literal sense. I didn’t commission an Amazon pilot to be filmed in Amsterdam. I didn’t audition Terry O’Quinn, Hana Mae Lee, and Mark Boone Jr to tell a haunting story. I didn’t even know Michael Dorman was from New Zealand until I started researching this essay.

But you also didn’t hire that precocious toddler to sprint down the sidewalk chasing a plastic bag, causing you to pause in your work commute, creating a mental image that lingered with you throughout the day, reminding you of a capacity for joy you’d forgotten since childhood. It’s for you even if it’s not for you. Not everything requires intention to have meaning.

V.

While pitching a superior on John’s suitability for the job, Tom Tavner offers one caveat: his son records folk music that, since his imprisonment and torture in Egypt following his prior assignment, has become “more honest.” That, we soon discover, is a laughable euphemism. John’s songs are explicit, detailed recountings of his operations as a NOC agent.

He doesn’t do this out of malice. John seems incapable of malice, even when he stabs people or threatens to out their infidelities. Nor does he do this out of a sense of whimsy, or thumbing his nose at authority.

If I had to guess why – and we do; no one ever ventures an explicit reason – it’s because John is starting to break apart under the strain of his job. He has a love of music and a quiet contemplation of the world. Music is the mask through which he can revisit his past and grapple with it. Without that, he has no closure.

We’ve seen this before in great works dealing with great traumas. Kurt Vonnegut made himself a character in Slaughterhouse-Five so he could revisit the firebombing of Dresden. Sylvia Plath documented the breakdown of her mental health in the guise of “fiction” in The Bell Jar. The act of creation forces a narrative distance that enables the author to manipulate the dangerous object at a distance.

But the beauty of really good art is that it doesn’t act as a safety valve for the creator. It functions that way for a select audience as well. It lets them know that their pain isn’t unique to them – that they haven’t been expelled from the community. And maybe it allows them to pick up the mask in turn and try it on, to see if it’ll shield them while they move some hazardous material from A to B.

This article has sold me on Patriot. Thank you!

This was great – and I share your difficulty in explaining the show because I think it’s all of the things you said, and more. One minor correction – it’s Luxembourg, not Amsterdam, where most of the overseas action takes place. Amsterdam was an event before the show started, where he smoked “the doobies” which caused the issue with the drug testing at McMillan.

Mark Boone Junior. Saperstein in this. Munson in ‘soa’