It’s way too premature to make predictions, but 2017 has already been an interesting year for online media.

For the last decade, the story of journalism has been declining subscriptions, dwindling ad revenues, consolidations, and shuttered doors. Yet the New York Times saw 276,000 new digital subscriptions in the last quarter of 2016. The Washington Post, after cutting staff for years, is adding 60 newsroom jobs currently. The Wall Street Journal saw a 300% spike in subscriptions on the day after the U.S. Presidential election. It would take months of similar spikes to make up for years of receding readership, but America’s new administration certainly promises to be newsworthy.

In the entertainment world, Chance the Rapper became the first artist to win a Grammy for an album released exclusively online. Spotify crossed 40 million paid subscribers last fall, with over 100 million users in total. Netflix will probably reach 100 million paying members in 2017.

TV and films are also acknowledging the prevalence of streaming. CBS’s The Good Fight, its follow-up to the critically acclaimed The Good Wife, is only available on its premium streaming channel. Amazon Studios’ Manchester by the Sea received six Oscar nominations, a first for a digitally streamed film.

And this is just the latest chapter in a continuing story. Netflix’s Beasts of No Nation won Idris Elba a BAFTA nomination and a SAG award, among many others. Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright have been nominated for Emmys every year since House of Cards premiered, and Uzo Aduba has two on her shelf thanks to Orange is the New Black.

That so many people are willing to pay for online media in 2017 won’t surprise you, if you look back at the trend of the last couple of years. But it will surprise you if you can remember the last twenty.

I started college in the fall of 1999. Living away from home, with my first laptop and my first local computer network, I discovered the joys of file sharing for the first time. The kids on my floor who had the most extensive collections – of mp3s, of movies, of adult clips and imagery – became minor celebrities. Once we could search across an entire network for specific files, the process became less like “sharing,” as we might traditionally recognize it, and more like a hive mind. Digital property was held in common.

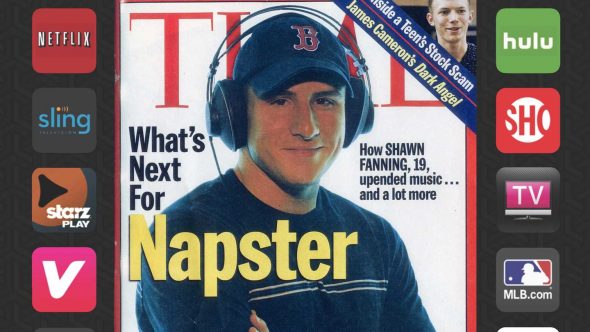

When Napster hit the scene around the same time, it felt like a natural outgrowth of an existing market. Instead of scanning my neighbors’ networks for a .mov of The Matrix, I could search around the world. Nobody told us at the time that we were on the cusp of a revolution, that we were about to topple broadcast radio, the record industry, and home movies. We just wanted that bluegrass “Gin and Juice” cover that everyone mislabeled as Phish.

After I graduated college, I got a laptop that could burn CD-Rs and roommates with much hepper musical tastes. Napster had disappeared in its original incarnation, but Limewire, Kazaa, and other filesharing services arose in its stead. My music collection broadened and deepened – indie hip-hop, classic electronica, New Wave post punk, and even the alt-rock resurgence heralded by Franz Ferdinand, Interpol, and The Killers.

It was also around this time I canceled my Blockbuster membership to join the new DVD service called Netflix. I could still find the latest and most popular films online a few weeks after their release, but no one was going to rip and seed the classics.

During this period, I was still libertarian enough to be tapped into online debates over filesharing. There was a prominent strain of traditional libertarian thought that venerated intellectual property as much as more traditional forms. But many of us, especially those on the Cory Doctorow end of the spectrum, saw IP as an outdated behemoth. We recognized that corporations like Sony cracked down on filesharing not out of an aesthetic love of artists, but as a means of capturing unclaimed profits.

But as vast as filesharing networks grew, it was impossible to save all the media one might want on one’s home computer. Companies that allowed online streaming crept to the fore. I first became aware of Pandora when it was a project to categorize all music on a series of scales – for melody, for genre influence, for “mood.” So when it evolved into an Internet radio app, I adopted it with little hesitation. If I discovered an artist I liked, I might still stockpile their mp3s through my traditional pirated means. But now I knew the cloud could provide.

Pandora gave way to Grooveshark. From Grooveshark, I moved onto Turntable.fm, very popular among the open-floorplan startups where I worked. Then my more connected friends gave me a beta invite to the US version of Spotify and I was hooked. Even my extensive collection couldn’t compete with every recording by any artist I’d ever listened to, or recommendations for those I’d never heard of. I discovered The National, Sugar Tongue Slim, and Black Joe Lewis and the Honeybears. I deepened my appreciation for The Replacements and Ted Leo. I fell in giddy adolescent love with Frank Turner and the Sleeping Souls.

I listened to Spotify’s free edition for years, tolerating the occasional ad for Bonobos or Stamps.com in exchange for access to the world’s library of music. When I realized I could install the premium edition on my phone, I finally made the jump. Removing ads was a bonus. Now, for $9.99 a month – less than the price of one new album a month – I can discover any commercial artist in the world, and most of the independent ones, in seconds. Except Taylor Swift, and frankly that’s her loss.

It took me a while to recognize the change I’d made. I’d gone from believing I would never again pay for music – why should I? – to paying a recurring fee every month. There was no great ideological shift involved. It was purely a matter of convenience. To download and manage all the songs I listen to in a week on Spotify would replace all my other hobbies and overheat my laptop. I’d evolved (or devolved) from a principled opponent of Sony’s intellectual property regime to a willing supporter.

And it wasn’t just in the musical sphere. When Netflix originally allowed limited movie streaming, I ignored the feature for months. The selection was miserable; they had nothing that I wanted to see, or that I couldn’t get through their DVD catalog. And I had to use Microsoft Silverlight, the worst means of consuming media since Mesopotamian clay tablets, to watch anything. At my subscription tier, Netflix enforced a 2 hour per month cap. I never hit it.

I wasn’t ignorant of the benefits of TV streaming. I had a Hulu account — still free back then — as a means of keeping up with current shows. Hot dogs and last week’s Burn Notice used to be a regular Friday night ritual. But I couldn’t imagine moving beyond that.

Then Netflix debuted House of Cards, which, if you’ll recall, was considered a longshot for them at the time. When my wife and I realized we’d hit my cap if we wanted to keep watching, I upgraded my subscription tier on the spot. Eventually, I canceled my DVD subscription entirely. I could never watch discs promptly enough to make keeping them cost-effective.

In the course of just over ten years, I went from stealing all my media to stealing none of it.

What drove this shift? Having more disposable income certainly helped. The increase in quality and the depth of content from streaming services has also been key. It takes me about as much time to queue up a movie on HBOGo, or a new album on Spotify, as it would to insert the appropriate disc. And once I do, I have access to a larger library than I could comfortably keep in my 1BR.

I don’t want to extrapolate too broadly from my experience. Media companies and researchers insist that piracy isn’t declining, merely shifting—from stolen files to streamed media. Instead of keeping one’s illegal .movs on one’s hard drive, now one searches for them on “the cloud” (i.e., other people’s hard drives).

But streaming video subscription revenue has tripled over the last six years, and is projected to increase another 40% in the next four. Digital music surpassed physical music as a source of revenue in 2015 and won’t be going back unless Pandora becomes conscious. This may not be enough to reverse the declines of the last decade. But it’s a safe bet that if media companies can find a source of revenue that’s actually growing, they’ll make it as enticing as possible.

Maybe not everyone will make the shift from piracy to, uh, privateering like I did. But the ranks of hardcore ideological holdouts must be dwindling, if only because hardcore ideology is rare. A child entering college in the fall of 2017 probably can’t remember a time before YouTube, and may have had access to Netflix streaming since before their teenage years. By the time they were thirteen, entering the peak period for forming nostalgic musical connections, they’ll have had Spotify, Google Play, Pandora, and countless other streaming services to inform their tastes. What will they share with roommates, neighbors, crushes? What new genres will they discover, and how?

This is where my own experience and the paucity of data limits me. Sound off in the comments, Overthinkers: how much media did you pirate / share during your peak periods? How much now?