Overthinking It is celebrating our nation by searching for the most American piece of pop culture with the word “American” in the title. Read the entire series

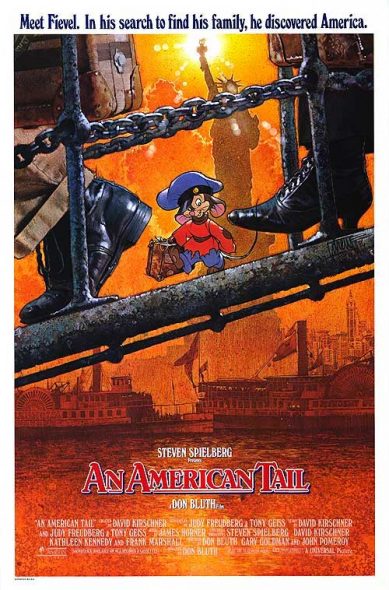

uch like the choice that faces America at the voting booth next week, the two finalists for the title of Most ‘Merican don’t have a lot of common ground. Tail celebrates its hero’s arrival to America by having a full choir sing the words to Emma Lazarus’ famous poem, “The New Colossus.”

uch like the choice that faces America at the voting booth next week, the two finalists for the title of Most ‘Merican don’t have a lot of common ground. Tail celebrates its hero’s arrival to America by having a full choir sing the words to Emma Lazarus’ famous poem, “The New Colossus.”

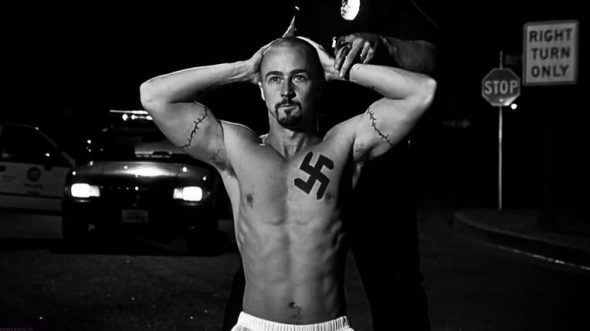

As it happens, Edward Norton’s character in American History X has some pretty firm opinions about this poem:

The question is not what vision of America we personally endorse; rather, we’re looking for the movie that is the most revealing about what makes America what it is. Is America defined by optimism and generosity, or fear and anger? Is Tail just a story we’ve been fed to mask America’s fundamental inequalities? Or is the hate on display in History X just a fringe movement?

There can be only one Most ‘Merican. Let’s settle this once and for all.

Round 1

The 2016 season of South Park focuses on the role of memory and nostalgia in contemporary American culture. The overarching plot of the season connects the rise of Trump (in the guise of Mr. Garrison’s hideously reactionary anti-immigrant presidential campaign) and the ceaseless string of reboots and sequels (most notably The Force Awakens) to a desire of many Americans to escape to a time when the world around them felt less complicated and easier to understand. The culprits fueling this backward-looking trend are Member Berries, tiny semi-sentient superfoods that constantly reminisce (mostly about Star Wars), and which lull the consumer into a haze of happy memories.

South Park‘s Member Berries are a useful lens with which to contrast American History X and An American Tail. Many of the skinheads in American History X appear to have a heavy dose of Member Berries in their daily diet, as they constantly talk about how their great their neighborhoods used to be, before they started to become more diverse. This nostalgia for a better life carries over to the the family life of the Vinyard brothers. Derek and Daniel’s father was a firefighter who died after being shot during an attempt to put out a fire in a house occupied by a drug dealers. Both brothers remember the time before their father’s death as a time when their lives were great – they were happy, well-off, and free of the cycle of hate and violence that followed Derek’s recruitment by white supremacist Cameron Alexander. But as Danny’s final flashback reveals, this myth of the perfect “good old days” is just that: a myth. Their father bullied and intimidated the whole family, pushing racist opinions about his kids being taught African-American writers in English class. Just as with the Member Berries, the nostalgia of many of American History X‘s characters is a fiction, a balm applied to cover up painful truths about themselves and their country that they would rather not acknowledge.

On its surface, An American Tail also seems to be subject to a healthy dose of Member Berries nostalgia. “‘Member Feivel? Yeah Yeah, I ‘Member. ‘Member No Cats in America? ‘Member Tiger? ‘Member the Stature of Liberty?” However, when I rewatched An American Tail, what struck me is how dark it was. What one is led to remember is not some mythical time in the past that made America great. New York City in An American Tail’s 1890s is hardly a time anyone wants to return, as it is rife with poor sanitation, political corruption, child labor, and many other social ills.

However, there is something else that An American Tail leads the contemporary viewer to remember, and that is a deeper sense of American-ness, a set of values that transcend any particular “good ol’ days”. What is inspiring about the film comes in small character moments – the small kindnesses in the Mousekewitz family’s Hanukkah celebration, Feivel’s irrepressible sense of adventure, the spirit of hope embodied in Henri the pigeon’s “Never Say Never”, and the diverse community of family and friends that come together in the end to reunite Feivel with his family. All of these moments caused me to remember moments from my own childhood, from right around the same time when I saw the film as a 5-year-old. They reminded me of lessons that my own family and community taught me about how to be a good person. But rather than being simple nostalgia for 1986, these lessons of An American Tail help to jog our collective memory about who we are as a nation. The greatness of our country isn’t that there are no cats in America, it is in working day-by-day to imagine a world where cats and mice love and support each other as one community.

– Ryan Sheely

Score: An American Tail 1, American History X 0

Round 2

This is Fenzel from the family bracket. I figured, first off, you needed to know my history and where I come from, because America is a place where half the country has no history and half is obsessed with where they come from, and there’s a lot of overlap.

We have two movies left obsessed with history and origin in different but American ways: for American History X, an American family with past so light it’s nearly absent, a present growing heavier, and the heaviest of futures, and in An American Tail, an American family with the heaviest of pasts, a lighter present, and a future that nearly flies away.

This is all very interesting, but amounts to deciding whether America ought to be happy or ought to be sad. And that is above my pay grade.

So instead of turning up or turning down (“For what?!” I say!), for the final round I must turn outward. Because both of these movies are drenched in style, and, despite battling their way to the finals, it’s time to acknowledge, here, before it’s too late and there’s nothing more to say, that neither of those styles are particularly American, but come from the outside.

Oh, they’ve been Americanized, but they feel imported without feeling foreign, like a Heineken at an Applebee’s.

And as such, I’ll make my call on this based on which foreign style choices in these movies feel to me like the most American of imports.

The mouse film is the journey of a bright, hopeful mouse in dark and dreary foreign land, full of horrors, traitors, moral turpitude and shattered promises. Moving so lightly, just touching the railings and ledges of the boundless industrial wasteland around him, he is buoyed up by his spirit, his imagination, and the dreams he shares with a spare few. His sister. His mama. His papa. For soaring intervals, he is giddy with joy, but then again too soon, he the world plunges him into suffering.

His city is on the brink of revolution: a revolution of mice against cats; that is, a revolution doomed to brilliant failure, and in the end, if not the now, to the abattoir. The hopes, dreams, spirit of the people are golden and beautiful, but the world is too cruel. And yet the mice dare to dream, and even the cats turn to mice, the mice to cats, and all seem to sing and dance.

Now, go back and and read those two paragraphs with a thick French accent. Perfect, isn’t it?

An American Tail owes a lot to French Romanticism and its descendants, but with a happy, sincere ending – think Steven Spielberg does Victor Hugo. Well, that would actually be called Hugo, I guess, and that’s about an orphan boy who lives hidden in public infrastructure, so that’s totally different, right?

French Romanticism brings us le vague de passions – the passion of the indeterminate – which can be seen in French Romanticism as the ultimate doom of the Revolutionary spirit, and from thence to various parts, including Dickens, his orphans and their Great Expectations. (Does it feel American to join a Revolution that takes to the streets, thrills the soul, but becomes captivated by a seemingly transcendent notion of possibility while failing to accomplish or sustain its major policy objectives? Pass the pinot noir and the heartbreak.)

An American Tail imports it, adopts it, and makes it comfortable – makes it fit our taste for what we expect. “Somewhere Out There” doesn’t speak to a lie, a transcendental signifier that confounds any system of meaning that incorporates it (How very French!), no, it’s about love and family and is as concrete and real as if it were cast in bronze and mounted in New York Harbor.

(By the by, you may note Fievel Mousekewitz is from Russia, but French Romanticism rose to prominence at a time when Russian intelligentsia generally spoke French, so let’s just assume a ton of cross-pollination there and move on.)

While An American Tail is remembered as adorable and turns out on rewatch to be surprisingly dark (more on that from my colleagues), American History X is remembered, I guess, as a gritty, hard-edged attempt at “realness,” and with that expectation in hand, becomes absurd and almost unbearable to see a second time, if you saw it the first.

Part of why X is so painful, I think, is that this expectation – which the movie invites upon itself with satisfaction, like the thunk of a tennis ball striking a roof-mounted light fixture – is severely at odds with what the movie’s goal turns out to be.

American History X is not about showing the world, or the streets, or whatever, “how it is.” The shifts from black and white to color, the lingering shots of beaches, the flashbacks, the music (the thundering, blundering music), the ham fist it drives through the screen with racist rhetoric.

American History X uses deliberately unrealistic, alienating, and confounding film techniques, replete with shocking imagery, in order to show how the storyteller’s emotional state has twisted his sense of the world and everything in it. It is about a man orphaned by his cruel father, betrayed and radicalized by his brother (who he has come to see as a hero even as he brings torment down on his home and family) who lives in a broken world surrounded by enemies and dies tragically as their sins inevitably become his own.

Yeah, it’s not exactly The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but both do involve flashbacks to public celebration that would normally be happy but is presented as twisted and nasty, where a bystander mocks and opposes the older protagonist before complying with him and later being murdered by him.

American History X is as German as An American Tail is French (meaning, through the lens of generations of interconnected global reinterpretation and influence), and specifically that it is Expressionistic, related by influence, tone and style to the art, film and theater movement from the early 20th century. According to Wikipedia (no shame in my game), Czech art historian Antonin Matějček in 1910 put it as such:

An Expressionist wishes, above all, to express himself… (an Expressionist rejects) immediate perception and builds on more complex psychic structures… Impressions and mental images that pass through mental peoples soul as through a filter which rids them of all substantial accretions to produce their clear essence […and] are assimilated and condense into more general forms, into types, which he transcribes through simple short-hand formulae and symbols.

Yeah, we’re looking at that thing one more time because we haven’t looked at it enough times through this tournament. Right.

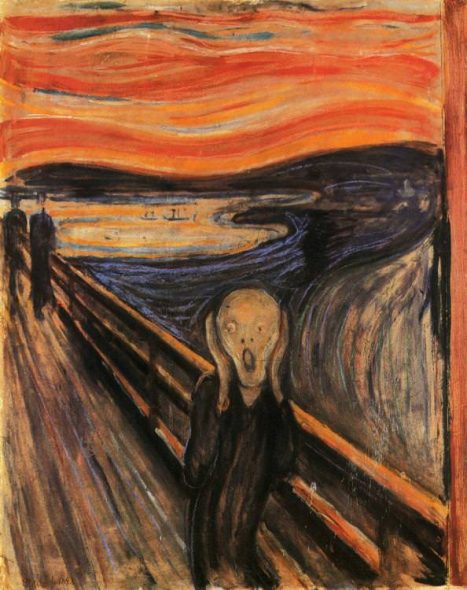

After rewatching it and thinking about it for all these weeks, I think the key to American History X is that it is not a cinema verite attempt to relay the otherwise untold story of what it’s really like to grow up as a white supremacist in Southern California (Even in the movie it feels more fantasy than reality to think people want such a story.); instead, the film reflects a vision of an emotional, subjective, idealized, alienated, iconic, clarified perception, where the sense of reality in general is warped by the emotions of John Connor as he recounts to Commander Sisko what happened to the guy from Fight Club who didn’t have a name but everyone calls Jack. It’s enough to make you want to scream.

Take it from a guy named Fenzel: of a little piece of Georg Buchner’s Woyzeck and a smaller one with Run, Lola, Run, this all feels German to me. Of course, there are also old German flags all over the frickin’ place, so it’s not like it was trying to tell you.

So, An American Tail is a French-style import, an object improbable freedom in a world of chains, spun by homegrown optimism.

And American History X is a German-style import, all feelings and meat and approximations of memories ground up with our own domestic produce.

But which is the better import? I can’t decide between hot dogs and the Statue of Liberty; I don’t want to give Joey Chestnut an existential crisis.

But I will say that An American Tail does a better job of being like the Statue of Liberty than American History X does of being a Frankfurter, because the latter, much unlike the sausage, declines to adapt its stylistic choices to make it palatable to its audience.

It’s a smart thing to do to products, and a painful, difficult thing sometimes to do to art or to people, but nobody said coming to America was going to be easy.

Both of these movies come to regard America, but one of them comes daring the world to shove it out, and one comes, for all its wandering, wanting to feel at home, and thus, we can feel at home with it.

And finally, since these are my last two Super-Sized sentences in this challenge of many weeks, I’d just like to add that the guy who created the story for An American Tail also created the animatronic Chucky doll and produced all six of the the Child’s Play movies.

There hasn’t been a good time during this thing to mention that yet, and I did not want it to go unsaid, because, like all truly great Americans, I believe that speech isn’t just a freedom, it’s an obligation.

– Peter Fenzel

Score: An American Tail 2, American History 0

Round 3

Stokes reporting in, from the Sex bracket. Nobody wants to be the guy who votes for the film with Nazis in it, huh? Well, me neither. I don’t want to. I want to believe in an America that has no use for X‘s catalogue of atrocities — white supremacists, curb-stompings, heavy-handed use of slow motion, etc.

And maybe I’m just getting swept up with patriotic enthusiasm, but you know what, I can at least believe in an America that doesn’t like those things. But that’s the America that X presents us with. An American Tail, on the other hand, sort of pretends that racism doesn’t exist. And it does so in a particularly un-American way. I’m talking, of course, about communism.

Certainly it’s not a CAPITALIST movie.

Look, you probably think An American Tail is about America being a melting pot, right? Because all the mice — the Italian mice, the Irish mice, the German mice, the Ashkenazi Jewish mice — they all come here fleeing persecution in their various homelands, and they all band together to throw off the feline yoke at the end of the film. From many, they become one. But the problem with that reading is that they are already one. They are all mice. They are a unified subaltern class, literally a different species from the oppressors that are holding them down. I’ll see you your “Somewhere Out There,” and raise you “The Internationale.”

Hobn ir gezen meyn eltern, fayn dame?

Is it really the case, do you think, that Feivel and Bridget would get along? That any random Russian-Jewish immigrant in America in the 1880s would have formed an immediate bond with any random Irish immigrant?Pretty sure it didn’t work that way: for starters, they’d none of them speak the same language. (And check out what Wikipedia has to say about the Whyos and the Max Eastman gang.) But if they’re not really Italian or Polish or whatever-all-else, if they’re really proletarian… then suddenly that instant solidarity starts making more sense.

Of course, the specter of racial prejudice does hang over the film, as it would any film that begins with a pogrom. But actually that pogrom proves my point better than anything else would: WHY do you suppose the Mousekowitzes were targeted for a pogrom in the first place? Because they were Jewish? That very well may be the subtext, it’s nowhere in the text that I can detect. What the text does suggest is that they’re getting targeted because they’re mice. Just like the Italian mice get targeted by the Italian cats. And so on.

Now, one of the central tenets of communism — at least the most familiar and simplified version of it — is that class is the only division that matters. Racism, on this reading, is just a way for the capitalists to play off one group of proles against another. (This means being racist is a form of false consciousness… it also sort of implies that being determinedly anti-racist is also false consciousness, at least in so far as it distracts you from the class struggle.) And this seems, broadly, to be the vision of the world that An American Tail subscribes to. And that’s both not American (in that it ends up pretending that racial prejudice is Not Even A Thing, which — for all its faults — is not a charge you can level at American History X) and un-American, in that it’s a no-good pinko commie ideology.

So yeah. I don’t want to vote for the movie with the Nazis in it. But I think I kind of have to. This is more of a vote against Tail than a vote for X though.

– Jordan Stokes

Score: An American Tail 2, American History X 1

Round 4

If An American Tail is our last best hope for a positive vision of the United States, we might be in trouble. On the surface, it appears that this movie doesn’t have a whole lot of nice things to say about America. The immigrants walk off the boat and straight into a gauntlet of con men looking to bleed them dry. They are hunted and killed in the streets by gangs of cats. Fievel has to escape from a sweatshop and ends up sleeping in “Orphan Alley” (yes, it has a sign) alongside hundreds of other shivering children. The politicians are hopelessly corrupt and so ineffective that the city’s richest mouse basically seizes control and nobody objects. There’s no law and order, no democracy, and the streets are not paved with cheese. So what is so great about America anyway? You’re looking at him.

In the entire film, there are only two characters who speak with a modern American accent: Fievel and his sister Tanya. Everyone else sounds either Russian, Irish, uptown hoity toity, or Brooklyn. This is doubtlessly to make these characters relatable, but I think there’s more to it: even though they’re fresh off the boat, these mice are already better Americans than the native Americans. Fievel is hopeful in the face of long odds, resourceful (he’s the one with the plan to escape from the sweatshop and get rid of the cats), brave to the point of recklessness, and kindhearted. While the America Fievel experiences is a disappointment in almost every way, a nation of Fievels would be a marvel, and that’s what we’re invited to infer about the present day country we’ve inherited. An American Tail isn’t so much a celebration of America as a celebration of the immigrants who made America. (Fievel is actually named after producer Steven Spielberg’s grandfather.)

But how does that pro-immigrant message look today? America is still the haven of choice for tens of thousands of huddled masses, but a lot of us seem unsure about whether we want them breathing free in our backyard. Donald Trump proposed a complete shutdown of all Muslims entering the country, and criticized Obama for admitting 10,000 Syrian refugees a year (infamously comparing them to a deadly bowl of Skittles). The sad thing is that 10,000 refugees is actually not a lot of refugees. In terms of its willingness to take in the unfortunate, Germany is mopping the floor with us.

Before we start feeling too bad about ourselves, we should remember that Americans of the past weren’t any more welcoming. All through the 19th century you could find “No Irish Need Apply” signs in store windows. During WWII there were strict quotas in place that prevented the rescue of European Jews until it was too late. For hundreds of years, Americans have been proud of their own immigrant heritage while similteneously believing that the place is full enough and we really don’t need any more immigrants. We love to read that poem on the Statue of Liberty and pat ourselves on the back, but remember the statue wasn’t our idea in the first place.

However, the tepid support for immigration doesn’t change the fact that for millions of people around the globe, America is a miracle. There’s an essay from Esquire magazine I reread when I’m feeling down about my country – just one page from a massive double issue, but I’ll never forget it. It’s a short profile of a family of Congolese refugees settled in Baltimore. The Bieleli family lives in what most of us would view as extreme poverty: seven people in a small apartment barely making ends meet. And yet, the parents are profoundly grateful to be here at all. “It is the first place in the world where we have been welcome,” says the mother, Kalanga.

This might seem like an odd thing to say about a country with so many Derek Vinyards, but everything is relative. The Bielelis barely escaped from the brutal ethnic cleansing of their tribe. The man, Mbunza, was set on fire. Kalanga was raped in front of her children. But in America, they not only have safety, they have hope.

Mbunza Bieleli. He is an American father now, so he knows what each of his children wants to be: “One wants to be a doctor; one wants to be a musician; one wants to be a solider.” Rubin, of course, is too young to say what he wants, so he is the only child for whom Mbunza speaks, in English:

“He is an American, so he will be president.”

America will break your heart nine times out of ten. Its history is riddled with empty promises and dreams deferred. To look at our divided, stratified, violent nation, it’s sometimes hard to imagine that our problems will ever be solved, or even acknowledged. America gives us every reason for hopelessness… and yet millions of people would still risk their lives and the lives of their families for a chance to live here.

Every country has its Derek Vinyards, angry right-wingers looking to blame outsiders for all the problems of society. But not every country has thousands of Fievels lined up to move there. America never lives up to the dream of America, but that’s a dream that has inspired every corner of the world to this day.

– Matthew Belinkie

Score: An American Tail 3, American History 1

Winner: An American Tail

And much like a half-drowned mouse in a bottle, we raise our weary eyes to see the promised land. After more than 40,000 words, we have our Most ‘Merican.

One thing that struck us is that when something has “American” in the title, the characters are probably going to have a miserable time. In Violence, the racist skinheads of American History X were at war with the tragic soldiers of American Sniper. In the Sex category, women were either objectified, manipulated, or resented, but seldom were allowed to have any agency of their own. The American Family was on the brink of murder in American Beauty, and it was a complete fraud in The Americans. And the American vision of Capitalism gave us the grifters of American Hustle, the violent world of American Gangster, and the vicious nihilism of American Psycho.

So it’s interesting that the most feel-good entry of our 32 competitors is the one that made it through. You could accuse the judges of grading on a curve, letting the optimistic children’s cartoon triumph over all the critical looks at the ugly parts of our society. But what’s more American than a Cinderella story, the little guy triumphing over the long odds? America invented the Hollywood ending, and here’s Fievel hoisting the trophy over the stunned and chastened neo-Nazis.

We have a saying for moments like this: “only in America.”

Will there be a post announcing the bracket winner? I’ve been out of the running since way back in round 1, but I’d be curious to see how well the finalists did.

The bad news is your bracket wasn’t great. You had three of the final eight, 1 of the final four (Pie), and neither of the final two. The good news is you were the only one to send me a bracket meaning YOU WIN! Email at [email protected] with your address and preferred t-shirt size, and we will pick out something glorious for you.

I just want to say this tournament is possibly my favorite thing you guys have ever done. Great job!

Thank you very much! We had a blast doing this – glad you enjoyed it too!

Did Ryan Sheely get to voice his input? Was he the first section? I was confused because Belinkie was credited as writer, so I assumed the first section was his, but he also got the last section, so now I am not sure. Thanks!

Sorry, we left off most of the bylines by accident – added them now. And yes, Sheely batted leadoff.

[gets up, checks election results] Whoops!

American History X would have won if we had used an electoral college.

“Does it feel American to join a Revolution that takes to the streets, thrills the soul, but becomes captivated by a seemingly transcendent notion of possibility while failing to accomplish or sustain its major policy objectives?”

I don’t know, does Occupy Wall Street ring any bells?