Overthinking It is celebrating our nation by searching for the most American piece of pop culture with the word “American” in the title. Read the entire series

hen we started ‘Merica madness, we built and seeded four brackets: Violence, Sex, Capitalism and Family, so that thematically related contenders would face each other on mutually relevant turf before taking on the heavier hitters from vastly different cultural niches. Once you’ve read this article, the four categories will have their champions, and they’ll be ready to fight for the championship.

But first, we need a knock-down, drag-out brawl to pare Capitalism and Family down to a winner apiece. The competition is fierce, spanning chasms of age difference and drawing on dozens of personal histories and a whole lot of miniature furniture available to purchase, or to ask for from your parents.

Where do we stand now? Click to enlarge!

Capitalism Regional Final: American Psycho (Book) vs American Gangster (Album)

It is fitting that our two finalists in the Capitalism region are both visions of wealth and power that are set in New York City. New York has long been a center of the financial resources that have fueled the American economy, as well as the advertising and media industries that provide the narratives that support consumer capitalism. Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho lives firmly within this world. Patrick Bateman works at a Wall Street investment firm, although we never actually see him do even a moment of work at any point in the novel. Instead, he spends most of his time at Manhattan’s elite restaurants and hot nightclubs. Most of these are on the Upper East and Upper West Sides, but a few are sprinkled throughout SoHo and Chelsea, foreshadowing the oncoming gentrification that would transform both neighborhoods in the 90s.

Jay Z’s arc through New York Elite society in the American Gangster album is different from Bateman’s. Although Jay Z also depicts a lavish Manhattan lifestyle on songs like “Roc Boys,” “Party Life,” and Success,” his story starts in the Marcy projects in a decidedly ungentrified 1980s Brooklyn. On “American Dream” Jay Z mentions how Harvard was “too far away” as an option to get him out of Bed Stuy; Bateman mentions at every turn that he went to Harvard for both undergrad and business school. Bateman is old money, the long-standing 1%, firmly entrenched in elite Manhattan social life. Jay Z’s rise to wealth is much more recent; even though the “Roc Boys” video features Jay and his friends wearing suits and ties made by the same high-end designers that Bateman fetishizes, that kind of wealth was nearly unimaginable when Jay Z was growing up back in Brooklyn.

This difference between the modes of wealth embodied by Jay Z and Patrick Bateman can also be seen in the role models that they reference again and again. Throughout American Gangster, Jay Z consistently makes the case that his appropriate peer group are gangsters who have lifted themselves from poverty to wealth through organized crime, rather than other musical artists. In “No Hook” he raps, “Please don’t compare me to other rappers/Compare me to trappers/ I’m more Frank Lucas than Ludacris.” On “Ignorant Shit,” he extends the logic, “Scarface the movie did more than Scarface the rapper to me/Still that ain’t to blame for all the shit that’s happened to me.” On “Fallin'” he namechecks The Godfather, Goodfellas, Scarface, and Casino all in one line. All of these role models share a similar image of a path to wealth through struggle, cunning, and ruthlessness.

Patrick Bateman has two different types of aspirational figures that he expresses deep admiration for throughout the book. First, Bateman has an unusual level of interest in serial killers and mass murders. Throughout the book he repeatedly interrupts polite dinner conversation to shares facts and details about notorious serial killers such as Ed Gein and Ted Bundy. Take one particularly notable exchange:

‘Do you know what Ed Gein said about women?’

…

‘When I see a pretty girl walking down the street I think two things. One part of me wants to take her out and talk to her and be real nice and sweet and treat her right.’ I stop finish my J&B in one swallow.‘What does the other part of him think?’ Hamlin asks tentatively.

‘What her head would look like on a stick,’ I say.

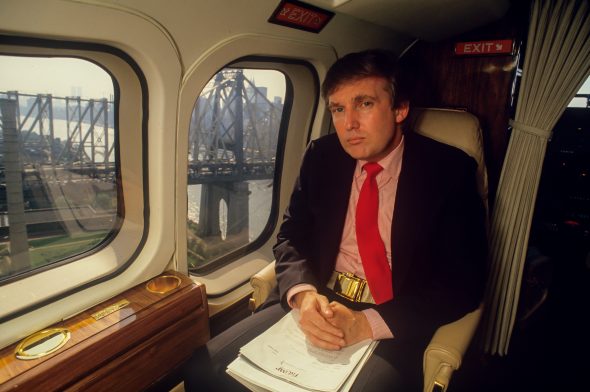

Despite Bateman’s fixation on serial killers, there is one figure he admires even more: Donald Trump. Although Trump never appears as a character in the novel, Bateman is fixated on him, always wondering if Trump or Ivanka are at the restaurant where he is, possibly spotting their car in traffic, changing his preferences about pizza places based on Donald’s reported tastes. These two sets of influences say something important about Bateman’s character. He aspires to accumulate even more and more wealth and to be recognized for his success. Trump in the 80s was the epitome of this goal, rapidly expanding his empire by building and buying more and more properties and putting his name on them. Bateman’s concurrent fixation on serial killers infuses his emulation of Trump’s world-conquering capitalist ambition with an utter contempt for the lives of others, viewing the people he encounters as objects of disgust (if not outright exploitation). This similarity doesn’t just flow in one direction. At his most disturbing (such as in both of the two recent debates and in many quotes from the Access Hollywood tape), Trump sounds eerily like Bateman.

For Bateman, his fixations on both Trump and the notorious serial killers are deeply interconnected, and both stem from a deep psychological need to be validated as an individual. Throughout the book, one of Bateman’s greatest sources of anxiety is being indistinguishable from the dozens (if not hundreds) of nearly identical yuppies who make up his economic and social milieu. The central paradox of Patrick Bateman is that even though he is among the richest 1% of all of New York, he is utterly unremarkable. The psychological unmooring that accompanies this of loss of identity is at the root of much of Bateman’s violence. In one moment of self-awareness he muses:

…there is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there.

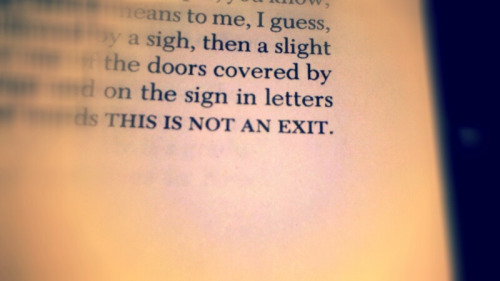

In this context, Bateman’s worship of both Ed Gein and Trump stems from a partially conscious desire to stand out from his peers, and to be recognized as noteworthy in some way or another. As the book progresses, he slips mentions of his heinous acts into more and more conversations, he becomes more brazen and public in his acts, he even calls his lawyer and confesses to all of his crimes, including murdering Paul Owen. And yet, nothing changes. No one reacts, no one hears him or takes him seriously, and the lawyer refutes his confession by saying that he had dinner with Paul Owen twice in London. This refutation is so strong that it raises questions about Bateman’s reliability as a narrator. Did anything that he depicts actually happen? Does any of it matter? In the end, the answer is no. The last words of the novel, “THIS IS NOT AN EXIT,” indicate that Bateman can’t escape the anonymous tedium of his yuppie life, in spite of his billionaire aspirations and serial killer actions.

American Gangster also copes with the psychological consequences of Jay Z’s choice to emulate his gangster heroes. In “Success,” he raps “What do I think of success? It sucks, too much stress.” Elsewhere, on “Ignorant Shit,” “Say Hello,” and “Fallin’,” he expresses the isolating effects of wealth (and of his particular gangster-inspired pathway), recognizing that he has become the villain, rather than the hero of his own life story. While this sense of alienation coexisting with vast wealth echoes much of what torments Bateman and motivates his endless cycle of murders, Jay Z has a very different coping strategy: he rolls the credits. Rather than ending the album with the downfall of the gangster (as his beloved gangster films would), Jay pulls a Will Smith and sings his own credits songs, “Blue Magic,” and “American Gangster.” While these songs don’t simply recap the album blow-by-blow, they step outside of the narrative of the album and recognize it as just that: a narrative.

At the end of “Blue Magic,” Jay Z emphasizes that even in spite of his current wealth, he is still connected to his origins in Brooklyn, rapping “Last of a dyin’ breed so let the champagne pop/I partied for a while now I’m back to the block.” In continuously returning to his roots (even just in his memory), Jay Z recognizes that his greatest success was simply surviving. While Bateman tries to escape the strictures of his socioeconomic class (and ultimately fails), Jay Z embraces his complicated economic story, and in doing so, succeeds. As Jay Z puts it in the closing line of the album, “Here’s to the man that refused to give up.”

– Ryan Sheely

Winner: American Gangster (Album)

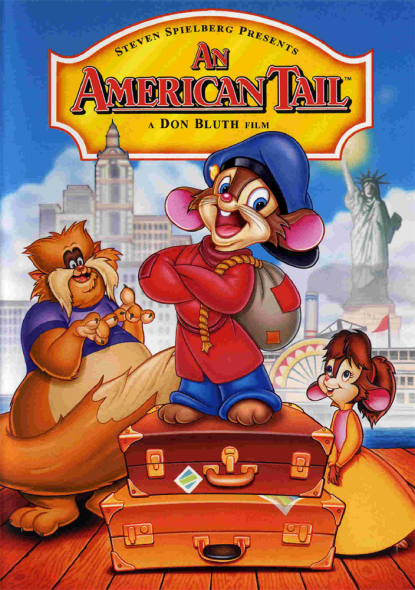

Family Regional Final: An American Tail vs Kit Kitteredge: An American Girl

On normal days, ‘Merican family members either cluster in their nuclear homes, or mind their business and keep their distance, ducking from city to city or state to state following jobs, schools, marriages, whatever comes next.

But then there are the special days, looming large o’er the cooler months. We travel hundreds of miles and dozens of hours to be together, carrying our duty, possibility, hope and more than a little stress. On these days, the ‘Merican family can finally talk about what we mean to each other, and what we really think about matters of great importance.

And so as we reach the final match in the ‘Merican family bracket, I did the only thing I could do – bring the family together.

I contacted every member of my immediate family, including my three brothers in law, and collected a big holiday conversation’s worth of texts and emails to decide the final match.

And since most of them have not seen a little-known HBO Films movie featuring Stanley Tucci as a thieving vaudeville magician, Joan Cusack as a mobile librarian, and Colin Mochrie as King of the Hobos, I made an executive decision and broadened Kit Kitteredge to the whole American Girl franchise: the Wu Tang Clan of luxury historical simulation, a series full of series, with dolls:

furniture and accessories:

books:

and, yes, movies:

about a posse of girls, originally from various American historical periods (the franchise has since expanded more broadly than I can explain here), all having analogous adventures transposed into different themes and circumstances.

What do you think is a better expression of what it means to be an American family: American Girl or An American Tail?

They all answered, like a true ‘Merican family, each in a style all their own, that I know and love, with varying levels of certainty, determination, political interest, and relation to the topic.

My eldest sister kicked it off, with a text from the town where we grew up:

Definitely American Tail.

Then she emailed me a copy/paste of the full Wikipedia plot summary of the movie, with her annotations in bold:

In 1885, Shostka, Russia, the Mousekewitzes, a Russian-Jewish family of mice who live with a human family named Moskowitz, are having a celebration of Hanukkah where Papagives his hat to his son, Fievel, and tells of a wonderful place called America, where there are no cats. The celebration is interrupted when a battery of Cossacks ride through the village square in an arson attack and their cats likewise attack the village mice. As a result, the Moskowitz home, along with that of the Mousekewitzes, is destroyed.

(Replace Russia with Syria and all those refugees fleeing to other countries when their homes are destroyed.)

The Moskowitzes board a tramp steamer headed for America. The crossing proves itself long and onerous, as well as the tramp steamer being buffeted by an angry sea. During a thunderstorm, Fievel suddenly finds himself separated from his family and washed overboard. Thinking that he has drowned, they proceed to New York Cityas planned, though they become depressed at his loss.

(May 26: over 700 refugees feared dead off Italy when boat capsizes;

June 3: Over 100 refugees feared dead when boat capsizes off Libya;

April 18: Over 400 refugees drown in the Mediterranean…

I don’t think I need to continue on this one.

Americans feel sad over these stories, and seeing washed up bodies of small children on the news… BUT we don’t want them here. )

However, Fievel floats to America in a bottle and, after a pep talk from a French pigeon named Henri, embarks on a quest to find his family. He is waylaid by conman Warren T. Rat, who gains his trust and then sells him to a sweatshop (Sold into sweatshops/sex trade in America now). He escapes with Tony Toponi, a street-smart Italian mouse, and they join up with Bridget, an Irish mouse trying to rouse her fellow mice to stand up to the cats. When a gang of them called the Mott Street Maulers attacks a mouse marketplace, the immigrant mice learn that the tales of a cat-free country are not true.

(When you come to America and can’t get a job, are discriminated against, can’t afford shelter and food… you realize the promise of the wealth and American dream are not true).

Bridget takes Fievel and Tony to see Honest John, a drunk but reliable politician who knows all the voting mice in New York City. (Sheldon Silver, Anthony Weiner anyone???) But, as the Mousekewitzes have not yet registered to vote, he can’t help Fievel find them. Meanwhile, his older sister, Tanya, tells her gloomy parents she has a feeling that he is still alive, but they insist that it will eventually go away.

Led by the rich and powerful Gussie Mausheimer, the mice hold a rally to decide what to do about the cats. (Occupy Wall Street) Warren is extorting them all for protection that he never provides. No one knows what to do about it, until Fievel whispers a plan to Gussie. Although his family also attends, they stand well in the back of the audience and cannot quite see that it is Fievel onstage with her.

(Big switch here from immigration to the fight against Wall Street by those who think Wall Street is evil.)

The mice take over an abandoned museum on Chelsea Pier and begin constructing their plan. On the day of launch, Fievel gets lost and stumbles upon Warren’s lair. He discovers that he is actually a cat in disguise, and the leader of the Maulers. (It would actually be quite funny if one of the guys arrested at Occupy Wall Street for sexually harassing women in the camp turned out to be [Goldman Sachs CEO] Loyd Blankfein) They capture and imprison him, but his guard is a reluctant member of the gang, a goofy, soft-hearted cat named Tiger, who befriends and frees him.

Fievel races back to the pier with the cats chasing after him when Gussie orders the mice to release the secret weapon. A huge mechanical mouse, inspired by the bedtime tales Papa told to Fievel of the “Giant Mouse of Minsk”, chases the cats down the pier and into the water. A tramp steamer bound for Hong Kong picks them up on its anchor and carries them away. (Just like how Trump will gather up all immigrants and ship them back home. The Giant Mouse is symbolic of Trumps great wall that will be built.) However, the giant mouse contraption along with a pile of leaking kerosene cans has caused the pier to catch fire, and the mice flee as human firemen, possibly the FDNY, arrive to battle it.

During the fire, Fievel is once again separated from his family and falls into despair when a group of orphans tell him that he should have given up looking for them. Papa overhears Bridget and Tony calling out to Fievel, but is sure that there may be another “Fievel” somewhere, until Mama finds his hat. Joined by Gussie, Tiger allows them to ride him in a final effort to find Fievel, in the end, the sound of Papa’s violin leads him back into their arms. The journey ends with Henri taking everyone to see his newly completed project—the Statue of Liberty, which appears to smile and wink at Fievel and Tanya, and the Mouskewitzes’ new life in America begins.

(The story ends with the true American spirit of never giving up hope, and deep down everyone still believing in the American Dream, and proud to be an American.)

Her husband, my first brother-in-law, had a different take:

Sadly, I was too old when An American Tail came out and never saw it. I’m hopefully too old now for American Girl, unless we’re talking about Tom Petty’s hit record, though I did take a 1998 movie quiz on Facebook recently and got 100%!

I informed him that “American Girl” had beaten “American Woman” in the Sex bracket, but had lost to Lana Del Rey, and I congratulated him on 1998.

My second-oldest sister weighed both sides in this missive from California:

I think American Tail is a more cohesive immigrant story, showing the cold harsh reality of the American Dream.

But American Girls have so many stories, including immigrant stories (Kirsten), but also snapshots of key moments in history and different communities.

American Girl also aims to be feminist and uplifting, but at the same time reinforces consumerism and superficiality for girls, like America!

And then conflict exploded on the scene, as my second-oldest sister confronted the oldest:

She is clearly anti-American Girl after I stole from her to support my Felicity addiction!

That was you??

You don’t remember the apology and then you icing me for a month?

I’ll score that one for American Girl.

Then my second brother in law dropped the follow-up:

Fievel wouldn’t even make it through our immigration process today. At the time, he was lucky to be in the sweatshop and not a detention center… imagine he washes up on Angel Island instead.

He’s also motivated by fear of cats, not family throughout.

Mom: Oh, that is so sad.

He resumes:

I go with conspicuous consumption and reductivist gender values in American Girl.

My youngest sister was next, with big block texts from the Rocky Mountains:

I think that American Tail tells a truer story of American political culture – in the beginning of the story you think it’s mice vs. cats and that in a place without cats the mice will be free and live in a general workers’ utopia. But who is arguably the most influential adversary in the plot? A fellow rodent – a con man who further exploits the young mouse. And the other greatest villain really looks like a mouse too but turns out to be a cat. And interestingly enough, it’s a cat who looks and acts most like a cat that ends up helping the mice the most.

At the same time, I think there are small pieces of the American Girl stories that perfectly embody our perception of these experiences – one that stands out is when Molly has to sit at the table to eat her turnips. Her dad is at war, her mom is helping with the war effort, so (I think) her neighbor cooks her dinner and she has to eat steamed turnips and cries at the dinner table while the turnips get cold even though she’s hungry. It isn’t until her mom comes home and puts cinnamon on them and reheats them that she eats and goes to sleep. The turnips are what she’s fixated on as a symbol of the change and loss she’s experiencing from the war, and she needs help processing it.

I asked her what side she was on.

… I think American Tail.

Then my third sister wrote in from New York State:

It’s a tough call for me. I’ve never thought about this before, to be honest…

I have more memory attached to American Girl.

And her husband noted with clarity and simplicity:

I would go with American Tail. It’s a great movie but also pretty sad with him getting lost in the city.

Mom: Yes it is.

My dad peppered me with texts on some different aspects of the movie and ideas of America, and when I asked for his thoughts on family specifically, he asked if he could write me an email. Of course he could. And here it is:

I haven’t seen AAT in a long time, so I might be light on detail. What I do remember is what resolved the crisis, and brought Fievel back into the embrace of his family.

AAT is not allegorical. It is too self conscious and too concerned with its superficial narrative for that. (This is good for a cartoon.) The narrative, however, does evoke some larger truths. For example, Fievel is cut off from his family, from the social order which had both threatened and protected him, and from the cultural idiom which made him feel secure in an insecure world.He was cut off from his past, adrift and powerless with only one purpose, viz. to rejoin his family. That is what gave his life context and purpose.

Without that familial context, Fievel is in danger of becoming a picaresque character, yielding to his immediate circumstances, and devoid of an objective, defining character, soul, and purpose. But a core of self asserts itself and he is saved from being digested by an indifferent world.

Fievel triumphs where lesser creatures fail. They resort to masks to define their social roles. These are not masks in the Pirandellian sense, which serve the absurd role of concealing the lack of a reality beneath them. The Rat’s mask has a reality behind it, but that reality is banal, vicious, and unredeemed. The Rat is really a Cat, a familiar evil from the past. This link to the past is the first step to the restoration of a meaningfrul life for Fievel.

This familiar evil from the past is overcome ultimately because Fievel is no longer in the old country. There the social order empowered and promoted the familiar evil. In America, the social order favors neither the old evil nor the mice. And so courage, virtue, and invention send the Cats packing.

All this, of course, is prologue to the moment when Papa’s familiar violin playing leads Fievel back to his “American family.” And what does that restoration to family do to and for Fievel? It shares love. It brings joy. It fulfills a meaning already there. It both accomplishes an old purpose and empowers a new one. That new purpose is quintessentially an American one: Go west, young man!

Hence, the movie’s sequel, Fievel Goes West

And finally, my mom:

I vote for American Tail ’cause I love that song!

FINAL SCORE:

American Girl: 3

An American Tail: 5

The Year 1998: 1

Mom: Such a touching thought that we can be far away but connected under that sky. Makes me teary every time.

Me too.

– Peter Fenzel

Winner: An American Tail

And that completes the Final Four! Click to enlarge!

Next week, we kick off the last stretch of the ‘Merica Madness tournament, with the first final four match between the winners of the Violence and Sex Regions: American History X and American Pie.

My vote is AHX and AAT in the ultimate Cynicism/Idealism showdown.

I hadn’t thought that far ahead because I’ve been focused on writing my pieces, but wow, that is a pretty amazing juxtaposition.

As much as I’m inclined to push for the winner from my region to go all the way, I also should disclose that I absolutely loved An American Tail as a kid. My family moved from Pennsylvania to Utah when I was 5 (shortly after the film came out), and “Somewhere Out There” was a song that was super meaningful to me as a kid trying to process feeling both distant from and connected to my relatives in PA. There is at least one video of me singing the song (in my own tiny off key mouse-like voice) in an elementary school talent show.

Ha, your mom and I are one. I was sitting here like “American Tail is the clear winner because that song is A++++.” In fact, I’m probably going to listen to it right now (again) as I have every time I’ve read one of your posts featuring it.

The song is remarkable. One thing I absolutely love about it is in the movie, the two kids that sing it are mediocre singers at best. The struggle with the high notes, they rush the tempo. They’re not terrible, but everybody went to elementary school with kids who are more naturally gifted singers.

And it totally works! The song is way more heartbreaking with the kids warbling through it than it would be if they got the girl from Annie to absolutely slay it. Really gutsy choice.