Overthinking It is celebrating our nation by searching for the most American piece of pop culture with the word “American” in the title. Read the entire series here.

oday we continue with ‘Merica Madness by returning to family and capitalism. If sex and violence are elements of American culture that lurk underneath the surface, family and capitalism play a much more central role in the stories we tell ourselves about what make our country great and in the political battles that heighten to a crescendo every four years.

oday we continue with ‘Merica Madness by returning to family and capitalism. If sex and violence are elements of American culture that lurk underneath the surface, family and capitalism play a much more central role in the stories we tell ourselves about what make our country great and in the political battles that heighten to a crescendo every four years.

If sex and violence are the fireworks, family and capitalism are the blanket, the picnic, and the hot dogs. If sex and violence are a sometimes-mysterious cascade of thousands of red, white, and blue dominoes, family and capitalism are the quixotic hours-long mission that drives some people to set up thousands of red, white, and blue dominos in the first place.

In other words, Round 2 of this challenge may have started with dessert, but gather the kids around the McNuggets, because it’s dinner time.

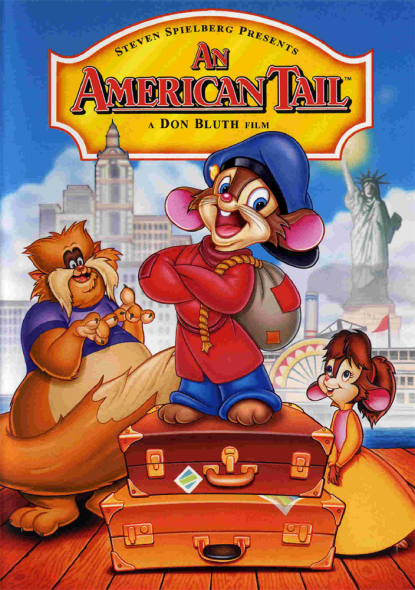

Family Round 2: American Beauty vs An American Tail

In round one, the family bracket traced the ‘Merican nuclear family: the key roles in the culture — narrower, as they are, than in life — and the archetypical perspectives of the Father, the Mother, the Sister, the Brother and the Dog — but there’s another figure in the ‘Merican family who didn’t get much of a say last round, and this round is all about… the outsider.

‘Merica is something of a land of outsiders, with settlers, rebels, runaways, refugees, the destitute, the trailblazing, the lonely, the ethnic, the foreign, the inconvenient — the ‘Merican family defines what is inside, but in raising its roof, it leaves uncovered a whole host of other folks. And, of course, roofs having houses and housing having doors, eventually questions and possibilities rise as to the in and the out of the family.

Each of our four Family Bracket contenders this week finds and regards the outsider (because if the family can’t be bothered to look outside its own problems, there’s no way it was getting out of the first round. I’m looking at you, American Chopper), and they will be judged by the nuance, the insight, the ‘Mericanness of what that mysterious figure brings to the table.

And we’ll start with the best-known family outsider of its decade, a defining titan of alienation, an Oscar-winning haymaker of a fifth-wheel, Ricky Fitts from American Beauty. Let’s brush aside the thick strata of parodies and snark built over two decades and confront the truth we all knew, even if we’d forgotten. Ricky Fitts is the worst.

Ricky is a super-creepy, edgy kid who trades in reasonable enough insights and participates in several reasonably successful and horribly botched sexual awakenings. Like Shane on his horse, or Paul Walker in his Honda Civic, he stares at the family with an intensity that promises depth and mystery, a libidinous infarction in the droning, functional misery of their domestic success.

Here’s why Ricky is the worst: Ricky has no boundaries, and the movie rewards him for it. He appears to have little to no awareness of the concept of privacy, or of privileged personal relationships – if someone seems to presume equal intimacy with everyone, has he really achieved intimacy with anyone? He’s not joking, like in Captain Ron (which if it were Captain American Ron would probably have made the second round), and he doesn’t have actual mysterious magical powers of social disconnection, like in The Boy Who Could Fly. He isn’t in opposition to much, and he isn’t magical at all. He’s just an intrusive douche.

And the Burnham Family appears to have very little in the way of boundaries – whenever they find a wall, they yell at it for a bit, and then just beg someone to knock it down.

This to me says the Burnhams don’t really have much of an “inside family” to even regard an outsider, which to me says they aren’t very ‘Merican after all. But hey, if everything has an equally mighty benevolent force behind it, even garbage, who’s to say Family even Matters?

Man, I wish there were an episode of that where Urkel used a machine to turn Ricky into a plastic bag so he figures out it is different from being a person.

I’ve already burned a ton of space for this, so there isn’t much left for An American Tail. But while Beauty has Ricky, who is the worst, Tail has Tiger, the cat who is friends with mice, voiced by Dom Deluise, who is the best:

One important characteristic of Tiger that isn’t shared by Ricky is that there is an apparent social reason for his outsider status – enmeshed in Dom Deluise’s own complex, campy gender performativity, and with his pink sweater and cuddly nature, Tiger comes off as some degree of LGBT, whether it’s that he’s a gay male cat, or he’s not fully expressing as a masculine cat and is somewhere on a gender continuum, or whether there’s something else going on. I’m not going to presume for Tiger without knowing.

But, unlike the difference between, say, a human life and a plastic bag to Ricky Fitts, the difference between the family and the outsider in ‘Merican culture tends to lean on something observable that actually presents a challenge of some kind, like race, class, gender, money, politics, health, age, or sexuality.

And, of course, Tiger is a cat. You have to be a pretty generous and kind-hearted family of mice to be able to share that dinner table.

In other words, since Tiger crosses a meaningful distance in connecting with Fievel, despite being such an outsider to his family and his people, he helps create the idea of family’s place in the world of the movie. And since distances and barriers don’t matter to Ricky, and the movie loves that, then it just makes the Beauty family look like not much of a family at all, and certainly not a ‘Merican one.

–Peter Fenzel

Winner: An American Tail

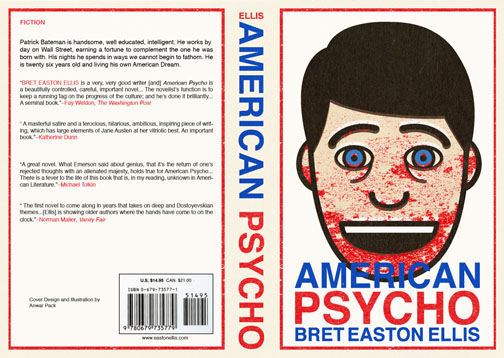

Capitalism Round 2: American Idol vs American Psycho (novel)

As I discussed in last week’s round of capitalism match-ups, the free market is at the core of how American capitalism is viewed in the popular imagination. At the core of this idea is the notion that the ability of individuals to engage in the free exchange of goods and services enables the kind of dynamism and innovation that drove America’s growth as an economic powerhouse. And yet, even with this emphasis on free exchange within markets as the basis of American capitalism, many popular treatments focus on the ways in which elements of hierarchy coexist within and around the market. For every image of equal individuals transacting freely, we see pop cultural images of bosses demanding TPS reports, oligarchs using their vast resources to bend every transaction to their advantage, and a government that regulates and enforces market transactions.

This tension between markets and hierarchies is the common thread that links American Idol and Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. Digging into how this theme is cashed out is central to evaluating the competing visions of capitalism presented in each.

To understand how American Idol engages with discourses around markets and hierarchies, it is worth recapping the basic structure of the show. The first several episodes of an Idol season are audition rounds- the panel of judges goes to a city, thousands of hopefuls line up for a chance to sing for the judges, and the judges then choose which of those contestants advance to the later rounds. In the later rounds of the competition, the judges still offer advice, criticism and feedback, but the decision about who advances and ultimately wins the title of American Idol is up to the voters at home.

As a result, the balance between markets and hierarchy shifts as a season of Idol progresses. The first stretch of the season is heavy on hierarchy; the judges are all-knowing and all-powerful, and they don’t hesitate to lord this over would-be contestants. This tendency was exemplified in Simon Cowell’s cruel, callous, and borderline dehumanizing critiques, which were a big part of the show’s draw in its earliest seasons.

As a season of American Idol progresses, however, the show’s shift from judges weeding out the unworthy to voters elevating the best contestants changes the vision of what the show is about. While the judges still comment, react, and guide, ultimately the viewers cast votes to decide who will win. Given that viewers are paying to vote, this transaction re-introduces the market, and turns on the (possibly dubious) assumption that whichever contestant inspires viewers to spend the most money (and time) voting for them will also inspire the most purchases of CDs (because those were still a thing when American Idol started).

If you have not yet read Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho and want to get a sense of what the experience of reading it is like, imagine taking the YouTube supercut of Simon Cowell insulting American Idol contestants, transcribing it, copy/pasting it enough times to fill 400 pages, and adding a dozen scenes of the most horrifying violence you can imagine, and that would get you much of the way there. To take one brief example:

These questions are punctuated by other questions, as diverse as “Will I ever do time?” and “Did this girl have a trusting heart?” The smell of meat and blood clouds up the condo until I don’t notice it anymore. And later my macabre joy sours and I’m weeping for myself, unable to find solace in any of this, crying out, sobbing “I just want to be loved,” cursing the earth and everything I have been taught: principles, distinctions, choices, morals, compromises, knowledge, unity, prayer – all of it was wrong, without any final purpose. All it came down to was: die or adapt. I imagine my own vacant face, the disembodied voice coming from its mouth: These are terrible times. Maggots already writhe across the human sausage, the drool pouring from my lips dribbles over them, and still I can’t tell if I’m cooking any of this correctly, because I’m crying too hard and I have never really cooked anything before.

While Simon Cowell’s unchecked, domineering criticism only dominates the early parts of any season of American Idol, Patrick Bateman’s judgmental, borderline authoritarian eye fills every single page of American Psycho. Bateman’s obsession over wealth and status are closely tied to anxiety over social power and control. Within his own circle of Wall Street investment bankers and fellow yuppies, these gradations are tiny, leading to a narcissism of small differences in which everyone dresses nearly identically and endlessly jockeys for authority by one-upping each other with esoteric knowledge of formalwear and ability to score reservations at exclusive restaurants.

Bateman’s constant losing battle for supremacy within his own social circle is ultimately displaced into his horrific acts of violence. Many of the most violent scenes in the novel (which far, far surpass what is depicted in the film) start with Bateman using his wealth to establish a relationship of extreme power vis-a-vis a vulnerable individual, acting as a manipulative, psychologically abusive puppetmaster. In these actions, Bateman’s drive to control crosses from social power into physical force. The most disturbing scenes in the book depict extreme acts of bodily destruction and dismemberment in extreme detail, and in many of these scenes Bateman progresses past even dismemberment and defilement to cannibalism.

American Idol presents us with the vision of the American economy that we want to believe in-hierarchy ultimately exists to help the market in its attempt to pick the most deserving winner. American Psycho presents us with an even darker version of our own reality, portraying a vision of an economic elite in which hierarchy is so entrenched, the rich literally kill and eat those who are less well off than them.

–Ryan Sheely

Winner: American Psycho (novel)

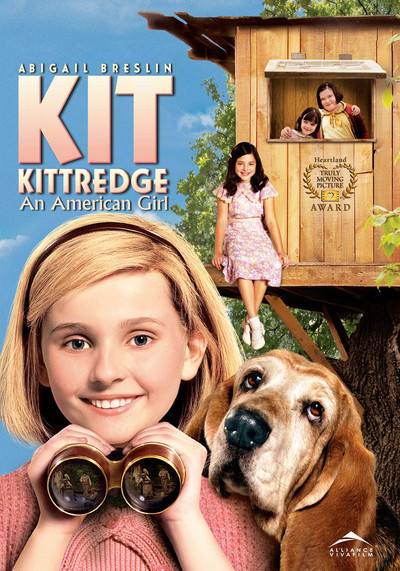

Family Round 2: Kit Kittredge: An American Girl vs American Dad

Putting aside the devil you don’t know for the devil you do, we get back within the four walls of the family bracket. And like Neil Diamond calling out the country’s name to the desperate around the world looking for safety, the culture of the ‘Merican family is writ with invitation. Someone will visit whom you do not expect, and the family will be proven by whether or how it opens its doors and shares its prosperity.

In other words, The Rockwell Freedom from Want table has a lot of turkey and a lot of chairs, and someone is coming to dinner.

And to take a turn from the Sidney to the Seth, we will judge American Dad! by the stranger he has invited into his home and how, the “fey pansexual alcoholic non-human,” Roger the alien.

Roger saves the life of the show’s eponymous Dad!, CIA Agent Stan Smith, four years before the events of the show, and as a sort of reward/mitigation strategy, Roger comes to live in Stan’s family basement. There, he serves as a sort of hard-drinking, coke-snorting Uncle Joey, providing periodic premise assistance, gags and nonsense: a comedy invested in comic relief from itself.

Roger isn’t always like this of course. He changes over the course of the show a little, and sometimes you get to see into his backstory, but the joke tends to arc in the absurd direction how little he cares about self-control or self-care, how petty he can get, and how cavalier he is, given the high stakes you would expect from an alien living among humans a-la-Alf, and how much the safety of everybody involved tends to be at risk during individual episodes.

What played to Dad!’s strength in the first round (its dyed-in-the-wool indifference) is here a weakness. The biggest problem with Roger as an outsider in a ‘Merican family, is that even though he’s an alien, and not very nice a lot of the time, and has a subaltern sexual self-identification, the family rarely seems to really have any problem with him.

Even when they’re upset, it’s either the flat sort of sit-commy upset where the yelling is for gags or for short-term plot and doesn’t really matter, or it’s the deadpan bewilderment that Family Guy made famous: passing the role of “straight man” by having every character at one time or another stand there stock still with giant eyes and tiny pupils when somebody else does something humiliating, dangerous, or socially awkward.

I like Brian from Family Guy a lot more than I like Roger as a member of the family, because both of them are clearly part of the family in a way everybody has stopped questioning to themselves, except Brian is a dog and Roger is an alien and those two symbols in the context of family life should not mean the same thing.

And as such Roger’s role in the family is muddy, and I think the whole family gets muddier by association. Which Roger would really get a kick out of, as long as they were all drunk. Or at least he was drunk.

Kit Kittredge: An American Girl has been the outperformer of the bracket so far, coming off its big upset against The Americans last week (Honestly, you play that matchup out 10 different ways, The Americans probably wins nine of them. But ‘Merica isn’t ‘Merica without underdog stories), and in this category it puts up big again, offering us a village of hobos.

Really, like An American Tail, and common to children’s stories, you could pick from any of a large number of outsider figures to help define and challenge the family norms (What is family? Who is our neighbor? Who deserves kindness, generosity, and hospitality? Who relieves us of the strain and boredom of staying at home with our families all the time, but that we never talk about, because we love our families and don’t want to hurt them, but don’t they drive us all crazy sometimes?).

But for this rather than delve into the delightful complexity of Stanley Tucci’s magician and Joan Cusack’s mobile librarian, I would address the hobo village specifically, especially so I could show a picture of Who’s Line Is It Anyway? star Colin Mochrie as a high-ranking hobo, which is a more realistic depiction of the emotional life of an improv comic than Don’t Think Twice could ever hope to be.

The image and feel of “the hobo” in the American mind is both good and bad, delightful and sad. There isn’t really that much of a difference between “a hobo” and “a homeless person,” but the difference in cultural resonance is huge. The hobo has been elevated in ways that feel similar to the elevation of pirates over robbers without boats, except that in turn reflects a deep and nasty cultural prejudice against the homeless in America.

But there’s something about placing a homeless man or woman on a boxcar in the 1930s that makes them harmless, it seems (though perhaps they were mostly harmless the whole time). Certainly Kit Kittredge sees it this way, jumping into friendship and alliance with various hobos over the course of the movie, which features among its several plots an elaborate effort to frame hobos for a string of muggings and home invasions across the Midwest, culminating in the entire hobo village sharing their food at Thanksgiving and the Kittredges inviting them to stay, and through this act of family of choice, Chris O’Donnell is spirited out of the ether for a happy reunion.

Of course, in a contest to find the most ‘Merican, internal contradiction is hardly a disqualifier. The hobos are pitied and glorified, they humble the main characters and also lionize them. They are a means in many ways, they are objects, but they are loved, and they are invited in. And we see many shades of complex and not-so-complex feeling for them.

And perhaps the most ‘Merican thing that happens here is the entire problem of transient homelessness during the Depression is framed in the context of the personal struggles of that one family – a family that aspires to credit for a sort of universal love in its altruism, that ultimately wins because it gets the money to keep its mansion. It is absurd, but also rings very true.

Because the ‘Merican family as a slide of ‘Merican life is sort of like a cake in a Looney Tunes cartoon. You see a very small slide made, but you don’t know until the slicer takes their share whether they cut a small piece for the family and left the rest for other people, or cut a small piece for other people, and picked up the whole rest of the cake for the family.

There’s something about cake and eating it too here. The hobo village would love any of the cake at all, but Roger would probably just turn the whole thing it into a joke about farting and doing quaaludes with Morgan Fairchild that would be forgotten by the next episode.

-Peter Fenzel

Winner: Kit Kittredge: An American Girl

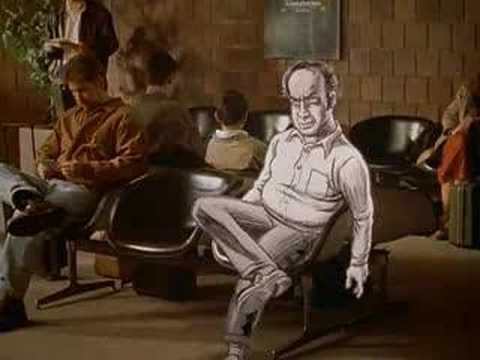

Capitalism Round 2: American Gangster (album) vs American Splendor

Despite their many differences, American Gangster and American Splendor actually share an important similarity: both are consciously multi-media in their conception and execution. American Gangster is a concept album that borrows many structural elements from gangster films, including the narrative arc of the rise, peak, and fall of a drug kingpin, an “end credits” comprised of two songs that essentially sum up the main themes and plot points of the preceding “movie,” and sampled dialogue snippets, both from the American Gangster film, and from a purpose-built dramatic monologue delivered by Idris Elba.

In contrast, American Splendor is a film that incorporates elements of comic books, by incorporating animated characters, drawn landscapes, and comics frames and panels. Rather than being fully animated sequences, these drawn segments interact with the actors and location filming in Cleveland, like a depressive midwestern Song of the South. As a film, American Splendor also draws on multiple traditions, combining the conventions of the narrative biopic with touches from documentary filmmaking, such as extensive interviews with the actual Harvey Pekar, and footage from Pekar’s notorious guest appearances on Late Night with David Letterman.

In both Gangster and Splendor, this technique mixing of elements from multiple art explores the nexus between art, commerce, and self-actualization. For Pekar, his American Splendor comics were unique in that the stories were autobiographical, but the drawings were by a rotating collection of artists, with each one drawing Harvey in their own style. In the film, this creates an interesting tension in which Harvey Pekar exists as a recognizable voice (both in his own voice, and Paul Giamatti’s spot on impression), even though there are many visual representations of Harvey- all of the various animated Harveys exist alongside Giamatti, the actual Harvey, and even the grotesque Harvey Pekar promotional doll created by Pekar’s third wife Joyce. This set of contradictions was at the heart of Pekar’s story. He was famous in his own way, yet continued to live a largely anonymous life in Cleveland. He had offers to license adaptations and spin-offs of American Splendor in many different forms, and instead resolutely continues to publish and maintain his comics as a resolutely indie enterprise. As much as Pekar was the brand identity of the American Splendor comics series, he continuously shirked efforts to define exactly what it means to be Harvey Pekar or to domesticate his own identity in the service of helping the comic to reach a larger audience. Even at the end of the film, Giamatti’s Pekar is still unsure of the value of his name as a symbol of a brand. As he asks in the final line of the film, “Who is Harvey Pekar?”

For Jay-Z the connection to gangster films provides a framework for turning difficult memories of a childhood growing up poor into a triumphant narrative of success. Even though Jay-Z’s own life story is substantially more complex and nuanced than the plot beats of a classic gangster movie, the film tropes provide a shorthand for understanding who Jay-Z is. He explicitly lays out the many different ingredients into the identity of “Jay-Z” in the second track on the album, “Pray”:

Look.. mind state of a gangster from the 40’s

Meets the business mind of Motown’s Berry Gordy

Turned crack rock into a chain of 40/40’s

Sorry my jewelry’s so gaudy

Slid into the party with my new pair of Mauris

America, meet the gangster Shawn Corey

Hey young world, wanna hear a story?

Close your eyes and you can pretend you’re me

I’m cut from the cloth of the Kennedies

Frank Sinatra, having dinner with the Genovese

In other words, how do you make a Jay-Z? Equal parts Sean Corey Carter, mobster, music executive, entrepreneur, fashion plate, politician, and entertainer. The equation embedded in this single verse sets up nearly the entire Jay-Z brand identity, and shows how even by the time of American Gangster‘s release in 2007, he was already a diversified conglomerate. Thus, while Harvey Pekar used his art to continuously resist creating consistency in branding, Jay-Z uses American Gangster to unify and amplify the alignment between his persona and personal narrative, and his many revenue streams. This difference is summed up by another Jay-Z line, from Kanye West’s remix to “Diamonds from Sierra Leone”: “I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man.”

–Ryan Sheely

Winner: American Gangster (album)

Next week we’ll find out which four pieces of ‘Merican pop culture will make it all the way to our Final Four. Come on back on Tuesday for the regional finals for Violence and Sex.

I feel AmTail has the edge over KitKit, mostly because Bluth really doesn’t shy away from the very real troubles that faced immigrants. Families fleeing pogroms, “We’ve been here slightly longer than you therefore we rule this area” street gangs, disenfranchisement by politicians.. serious biz.

This is shaping up to be a battle of Idealism vs. Cynicism, but not gonna lie, I really really really want Idealism to win. It’s built into America the Dream™:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tos[sed] to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

I get sniffly when I think about that, and then the tears burn up in rage at the likes of Trump and his ilk 100% ignoring everything the real America is supposed to stand for.