Overthinking It is celebrating our nation by searching for the most American piece of pop culture with the word “American” in the title. Read the entire series here.

he first round had its share of upsets. American Dad! dispatched the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel American Pastoral. The Jesse Eisenberg action comedy American Ultra assassinated crowd favorite American Gladiators. The Christian Bale movie American Psycho didn’t even make it to the main bracket, losing in a play-in game to the book version. Try getting a reservation at Dorsia now, Christian Bale!!

he first round had its share of upsets. American Dad! dispatched the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel American Pastoral. The Jesse Eisenberg action comedy American Ultra assassinated crowd favorite American Gladiators. The Christian Bale movie American Psycho didn’t even make it to the main bracket, losing in a play-in game to the book version. Try getting a reservation at Dorsia now, Christian Bale!!

Here’s how things stand after Round 1. Click to embiggen!

Today we’ll narrow down Violence and Sex to two competitors each, setting up next week’s regional finals.

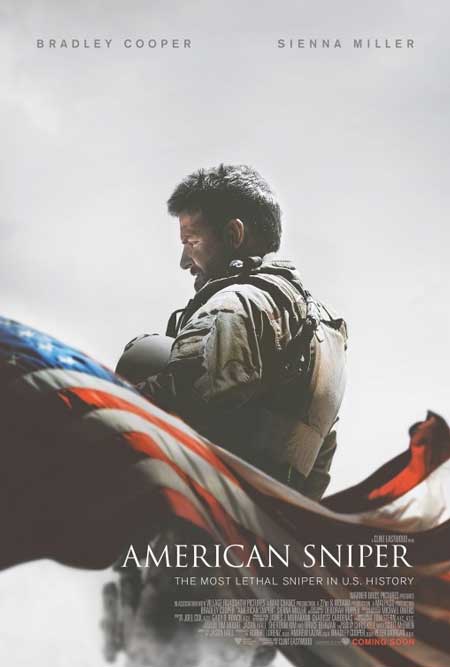

Violence Round 2: American Sniper vs American Ultra

Let’s talk about violent men and the women who love them.

At the beginning of American Ultra, Mike and Phoebe are in the kind of adorable relationship where he calls her in the middle of the day to share a cool idea for a comic book. The only “problem” is that she’s smarter, more capable, and more accomplished than he is. This is fine with her, but Mike’s obviously embarrassed about it. “We were the perfect fucked-up couple,” he says in voiceover. “She was perfect, and I was the fuck-up.” The town’s sheriff also doesn’t think much of their modern relationship. “You’re his girlfriend. You’re his mom,” he sneers with withering disdain. “You’re his maid. You’re his landlady.” The fact that he clearly makes her happy isn’t enough for anyone but her.

The activation of Mike’s suppressed assassination skills changes everything. First off, Phoebe gets captured, giving Mike an opportunity to utter that oldest of cliches, “I’m going to save my girlfriend!” And save her he does, brutally killing a dozen men. And then, covered in the gore of his vanquished enemies, he drops to one knee and proposes to her. The violence has reestablished traditional gender roles, neutralizing Phoebe’s skills and talents and rendering her helpless. I think it’s meant to be a cute ending. But I couldn’t help but think of dozens of real life stories of jilted men and pissed off husbands who resorted to violence to establish dominance. There’s a Margaret Atwood quote that gets trotted out in the comments sections under those articles: “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.” Phoebe doesn’t laugh at Mike and Mike doesn’t try to kill her, but the fantasy of regaining your “man card” with a gun is a powerful one.

But the movie actually goes one step further to show that the couple’s future together is inexorably linked to Mike’s talent for killing. In the coda we see them in some exotic hotel, dressed to the nines. But they’re not there as equals: Mike is working for the CIA, and Phoebe is now his handler. On some level that’s teamwork, but it’s clear that Mike is the important one now and she’s there to support him. Violence has allowed Mike to provide Phoebe with a lavish lifestyle, but more importantly (the movie implies) she’s not the one wearing the pants anymore. Indeed, the final scene is the only time we see Phoebe in a dress, in full arm-candy mode.

American Sniper tells almost the opposite story. Chris Kyle and Taya get together while he’s still in training, and they’re married before his first deployment. In fact, the orders to ship out coming during the wedding reception. Throughout the movie, violence is something that pulls the couple further and further apart. He’s absent almost all the time. When he calls home, his conversations often end in a burst of gunfire that leaves Taya hysterical. (Do all soldiers make personal calls from the front lines?) When he’s back in Texas, he’s distant and unable to connect. He’s prone to bursts of rage that make us worried for her and the kids. After Chris’s final tour, he’s so hollowed out that he doesn’t even tell her he’s back in town – he just sits in a bar by himself.

So violence doesn’t make relationships, it breaks them. “I do it for you,” Chris tells Taya. “Your family is here,” she spits back. “Your children have no father. We’ve sacrificed enough.” His intentions may be noble, and his service may have a positive impact on the world (maybe – that’s a whole different conversation). But his marriage and family are part of the price he pays. The final piece of the movie is about Kyle’s struggle to adjust to a peaceful life, but even his best efforts involve guns. In the final scene, he creeps around the house with a pistol, playing cowboy. His wife and kids are delighted, but the audience has a moment of doubt about whether we’re seeing some kind of deadly mental breakdown. Chris turns out to be fine, but the shifty veteran waiting outside is tragically not.

These movies are two sides of the same coin. American Ultra presents a popular and dangerous fantasy that the way to earn a woman’s respect is through kicking ass and taking names. (Think about True Lies, where Arnold’s marriage is about to implode before his wife learns the sexy truth about his job, or Wanted, in which James McAvoy starts out meek and cuckolded and gets to sleep with Angelina Jolie after he becomes an assassin.) American Sniper presents the reality that violence poisons domestic life. The more legendary and unstoppable Kyle is on the battlefield, the more useless (and maybe even dangerous) he is at home.

The question is whether to grant the W to the fantasy or the reality. In this case, I think box office is revealing. American Ultra was a bomb, and American Sniper broke records. This suggests to me that in an age of mass shootings and endless war, the fantasy of shooting your way to happily ever after isn’t as fun as it used to be. Sniper racks up another kill.

– Matthew Belinkie

Winner: American Sniper

Sex Round 2: American Girl vs American

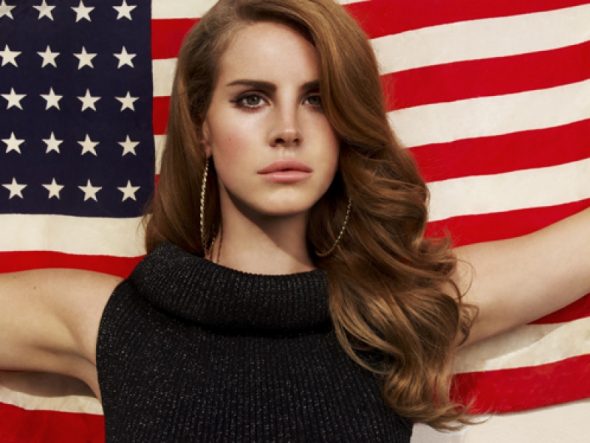

Oddly enough, given that the first round of the Sex bracket’s musical subdivision was segregated by gender, the winning songs both turned out to be about women’s experiences. Tom Petty’s “American Girl” is about a woman alone: a bittersweet meditation on the curdling of hope. It’s not really about an American girl, it’s about the woman that the girl grows into. She WAS an American girl – not anymore. (Even verse two, where she thinks back on her childhood romance, took place at some point in the past.) Lana Del Rey’s “American,” on the other hand, is about a woman in love: her guy isn’t in the past, he’s right there in front of her, making her crazy. And she’s just fine with that.

It’s tempting to say that this matchup boils down to optimism vs. pessimism. Is American romance about presence? Or about absence? Are we a nation of Saturday nights, or one of Sunday mornings?

But ultimately, I don’t think you get to have one without the other. They’re different stages of the same grand cycle. Americans are obsessed with their sex lives, and there’s nothing more American than throwing yourself wholeheartedly into a relationship when you’re in that moment. But Americans are also obsessed with the consequences of sex, and there’s nothing more American than ruefully looking back on what a god-damned mess it all was (or, when it’s somebody else’s sexual past on display, than pointing and laughing). Neither attitude makes the slightest bit of room for the other. They’re mutually exclusive; they’re also both totally true. Time, man. Right?

But “American” gains a small but decisive lead through its constant pop-culture references. One of the main ways that Lana bonds with her guy is through their shared appreciation of specific musicians: the Crystal Method, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis, and – why hello there, the competition – a subtweeted reference to Tom Petty in the “… hell yes / Honey put on that party dress” line.

The greatest aphrodisiac of his generation. He actually was, though!

What does pop culture have to do with sex? Well, as anyone who’s ever been on a date knows, showing off your good taste in books/music/movies/whatever is a big part of how you try to make yourself seem worth the trouble of screwing. (I mean… this was always a big strategy for me, and I’m guessing for everyone else who comes to this website. I have no idea how normal people do it. Maybe they just talk about sports and financial products.) So just in that “American” acknowledges this aspect of romantic interaction, it’s more realistic than “American Girl.”

And the clincher is the fact that most of the bands “American” mentions are American icons. We’ve already established that reciting your musical taste like this is just a roundabout attempt at looking sexy. So in this case, sexy taste in music = egregiously American taste in music. The question we’re faced with, then, is this: is American-ness, itself, sexy? Well, that’s arguable… but is it ‘Merican to think that American-ness is sexy?

Oh my my. Oh hell yes.

– Jordan Stokes

Winner: American

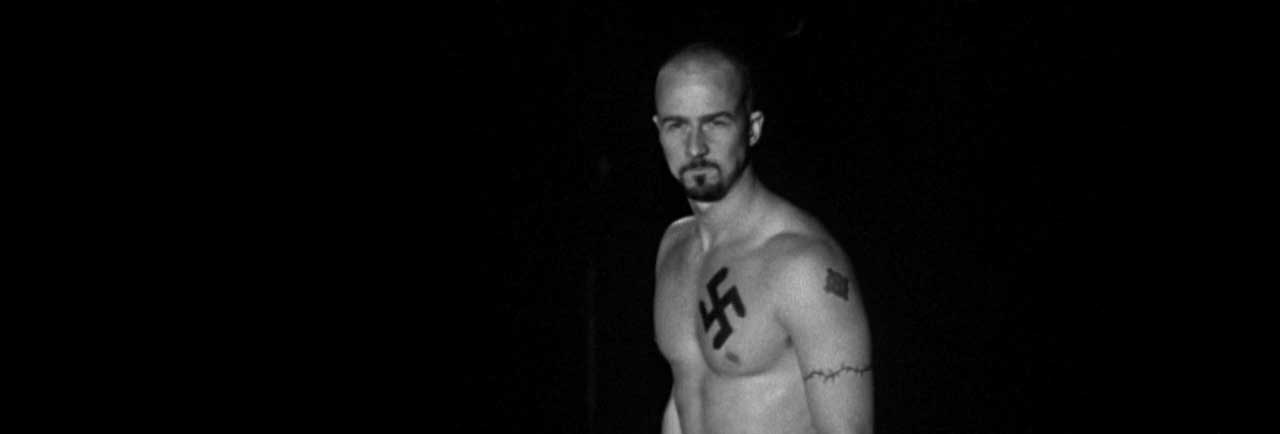

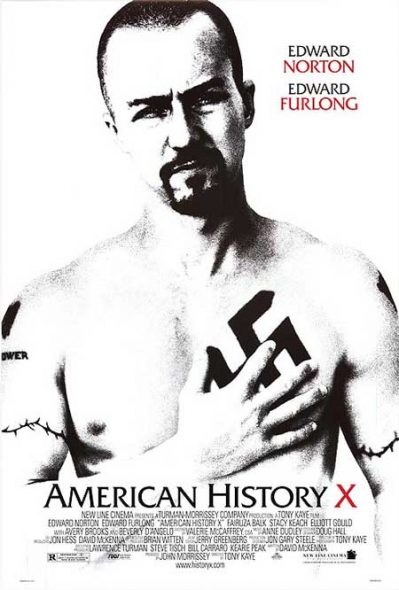

Violence Round 2: American Ninja vs American History X

In America, is violence a team sport? Our pop culture mythologizes the solo badass, from John Wayne to John McClane. But we also love stories about teamwork, from The A-Team to the Avengers. Do we want Batman the solo crusader, or Batman the brains behind the Justice League?

I’m assuming most of you aren’t familiar with American Ninja, so bear with me for a minute. The very first scene sets up the central conflict of the James Deanesque loner versus an organization that demands teamwork. It also includes some sweet hacky sack action:

When Joe’s convoy is hijacked, the officers tell everyone to surrender the equipment without a fight. Joe ignores them and springs into ninja action, getting a bunch of other soldiers killed in the process. Back at the base, the other enlisted men led by Corporal Jackson, surround him and glower threateningly. “We pride ourselves on teamwork here,” Jackson says. “We left all the glory boys back in Vietnam. Because glory boys like you get people killed.” Does Jackson means that the Vietnam War was lost because there wasn’t enough teamwork? Or is he saying that anyone who didn’t conform got fragged?

Fast forward a bit. Joe knows who is hijacking the convoys, and he knows his sergeant is in on it. Joe plans to deal with things in the ninja way, but his girlfriend and Jackson (who has warmed up to him for no apparent reason) plead with him to go to the base’s commanding officer for help:

Patricia: You gotta trust somebody sometime. If I mean anything to you, please trust me now.

Joe: I can’t.

Jackson: We’re the only two people you can trust.

Patricia: Please, Joe.

Joe: OK. Let’s go.

It’s a big moment. An intervention. No wait… a NINtervention. (hold for laughter) The loner is willing to give teamwork a try and respect the chain of command. He goes to the Colonel with the whole story… and then the Colonel promptly calls the guards on him because he’s part of the conspiracy too. Yes, the guy in charge of the base has been cooperating with the ninjas to have his own equipment stolen. But it’s not out of greed; it’s for the greater good, as the bad guy reminds him:

What about those you are trying to help? Have you forgotten about them? Without this, their country could fall to the communists. One more domino down. Who knows what country will be next?

This fascinates me. In American Ninja, the instruments of institutional violence are rudderless and corrupt. There’s a post-Watergate, post-Vietnam climate of lies and cynicism. And what America really needs, the movie tells us, isn’t obedient soldiers but unstoppable killing machines who are going to disobey orders and get the job done. In the final reel Joe goes after the bad guys alone, and the army arrives to back him up in the nick of time. The lone cowboy has redeemed us from our bureaucratic malaise. (Interesting fact: American Ninja came out the same summer as Rambo II, another movie where the commanding officer betrays the super soldier under his command.)

American History X is also about a soldier at odds with his army. Derek Vinyard is a white supremacist hero, but he has a jailhouse epiphany and wants to put the scene behind him. However, he can’t just log into Facebook and unfriend the Venice Beach Skinheads (for starters, this was 1998 so Facebook didn’t exist yet). When he goes to gang party to tell them he’s out, it quickly escalates into an angry mob denouncing him as a race betrayer.

It turns out the only thing more dangerous than being in a gang is NOT being in a gang. In prison, he abandons the skinheads after he catches them dealing drugs with the Latinos, putting profit before racial purity. This leads to him being brutally raped by his former allies, and nearly shanked by everyone else. Once out of prison, it looks like the pattern is going to repeat itself: his former best friend pulls a gun on him, and a black gang drives menacingly past his house in the middle of the night. All Derek wants is a clean start, but can there be a clean start for a guy with a swastika tattooed over his heart?

And if he can’t even get himself out of the gang, what hope does he have of changing anyone’s mind? “You don’t need this, Stacey,” he tells his girlfriend. “You’re crazy,” she tells him. “We are ten times what we were and we are bloody organized.” For people like her the gang is a source of identity, and they’ll fight to hold onto it. Towards the end of the movie his Derek’s former teacher asks him to help prevent anymore violence. Derek’s hopelessness is palpable. “Do you know what you’re asking me to do?” he says bleakly. “Yes,” Sweeney tells him. “I’m asking you to do whatever’s in your power to do.” Spoiler alert: it’s not much. (The next year Edward Norton would find himself in a similar scenario in Fight Club, when he started Project Mayhem and then found himself unable to shut it down. His own guys try to castrate him.)

So while American Ninja says that an individual with a gift for violence can reinvigorate a corrupt system, American History X says that the individual is nothing compared to an organized system of hate. Derek is the most charismatic, most physically and rhetorically gifted member of the gang, and it takes them about five minutes to denounce him when he stops toeing the party line. There’s no changing the system and there’s no escape from it. There is no American Ninja coming to save us.

But here’s one more glorious clip before we say goodbye:

– Matthew Belinkie

Winner: American History X

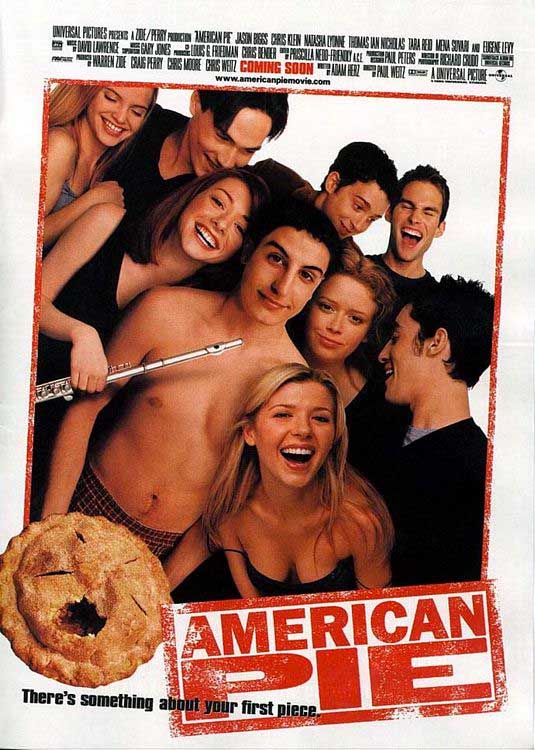

Sex Round 2: Last American Virgin vs American Pie

The first thing to point out is that these are very, very similar movies. Within the broader genre of the sex comedy, there’s a sub-genre of essentially plotless movies about high school guys trying to get laid. Last American Virgin and American Pie both fall into this category. In the first round of this contest, we often found ourselves comparing apples and oranges. The risk here is that we’ll end up comparing an apple with that-same-apple-but-in-1982.

Still, it’s not like there are no differences between the movies. Take, for instance, the category of “acceptable sexual sins.” By this I mean something that the characters do which the film presents as deviant and immoral, but which isn’t bad enough to make the audience lose sympathy for the characters. Here’s how that shakes out:

Acceptable Sins in American Pie

- Videotaping a naked lady without her consent

- Sex with inanimate objects (pies, flutes)

- Sex with a much older woman (slash a much younger man, although I doubt we’re supposed to think about Stifler’s Mom’s agency all that much)

Acceptable Sins in Last American Virgin

- Hiring a prostitute

- Sex with a married woman

Interesting contrast, don’t you think? The prostitution thing, in particular, is not so comfortable to watch – not when you consider that these boys are high school students. (I do wonder if this is the Israeli filmmakers failing to account for a certain puritanical streak in the American psyche. We can have films about hookers with hearts of gold, where the sex is still romantic sex. There are plenty of those. But it’s super weird to see the heroes of the piece having transactional sex with a prostitute, despite that being, you know, what prostitution actually is.)

Another big difference between the movies is that The Last American Virgin recognizes that there are consequences to sex. Both pregnancy and VD make appearances in this movie! American Pie saves all it’s boning for the final act, so it ends too quickly for this to be a factor… but it’s pretty clear that it never would be. “Consequences” is not a concept that the American Pie franchise has much use for. On a related note, The Last American Virgin is notable for containing an abortion subplot in which the only thing that anyone worries about is finding the money to pay for it. This feels decidedly un-‘Merican… can you imagine that happening in a movie today? With NO hand-wringing?

But the biggest difference in the movies is the way that they end. You all probably remember American Pie’s ending, right? Everybody has sex and then goes off on their respective merry ways, each changed for the better by his experience (slash her experience, except that again, female agency, lack thereof, yadda yadda yadda I’m a broken record here). But oh man, the ending of Last American Virgin.

So, here’s the deal. Like I said, the movie’s just a series of vignettes, but the central vignette is about a love triangle between Gary, the sensitive, kind of loser-y guy, Rick, the cocky handsome guy, and Karen, the new girl in town. If you want to mentally slot American Pie cast members into these roles, Gary’s probably the Jason Biggs, and Rick is the Seann William Scott. (Karen’s possibly Tara Reid, although she doesn’t really have a good analogue.) Anyway, about halfway through the movie, Rick gets the girl. And then he immediately gets her pregnant. And then he immediately breaks up with her.

In swoops Gary to help pick up the pieces. (You’re probably getting flashes of Fast Times at Ridgemont High, here, and the comparison’s apt — although they seem to have developed independently.) He spends all his money plus all he can borrow to help pay for her abortion. He takes care of her while she recovers from the procedure. They bond. He says he loves her. They kiss. And then, a week later, he shows up at her eighteenth birthday party – only to find her making out with Rick.

(Like I said last time, this movie really fricking hates women.)

But that’s not the shocking part. What’s shocking is that the movie just ends right there. There’s no confrontation, no sense that anyone grows or learns anything. Instead, Gary staggers out of the party and begins to drive home, weeping, while the credits just roll over the footage of his crying face. You have to see this:

So that gives you a taste. But you know how movies are: there’s a lot of credits for them to get through, and it’s not like it fades to black right away or anything. He just… keeps… crying! And that’s the end! It’s a Lars Von Trier solution to a Saved By The Bell problem.

As with the “American Girl” vs. “American” matchup, we’ve got one movie that’s basically about how awesome sex is, and another that takes a savage right turn into “we die alone and sex is awful” territory somewhere around the third act. Again, I don’t think that obsessing over the consequences of sex is un-American… but the end of Last American Virgin is actually more of a slam on romance. We already dealt with the consequences of sex! That’s what the abortion scene was for! No, the message of Last American Virgin is that falling in love is stupid and weak. Oh, and also: “If you think you’re a loser, you’re probably right, and what’s more you will always be a loser. Someone else will get the girl. Not you. You get nothing.”

America believes in happy endings. If nothing else, America has hope.

– Jordan Stokes

Winner: American Pie

On Thursday, we’ll see who will advance in Family and Capitalism. Stay tuned, my fellow ‘Mericans.

Add a Comment