Overthinking It is celebrating our nation by searching for the most American piece of pop culture with the word “American” in the title. Read the entire series here.

f Monday’s play-in matches are any indication, the Capitalism region of the ‘Merica madness tournament is going to feature positively brutal competition. Brett Easton Ellis’s American Psycho novel dismembered the Christian Bale-starring film, and Jay-Z’s American Gangster album executed Ridley Scott’s film version with a brutality that would have shocked even Frank Lucas.

f Monday’s play-in matches are any indication, the Capitalism region of the ‘Merica madness tournament is going to feature positively brutal competition. Brett Easton Ellis’s American Psycho novel dismembered the Christian Bale-starring film, and Jay-Z’s American Gangster album executed Ridley Scott’s film version with a brutality that would have shocked even Frank Lucas.

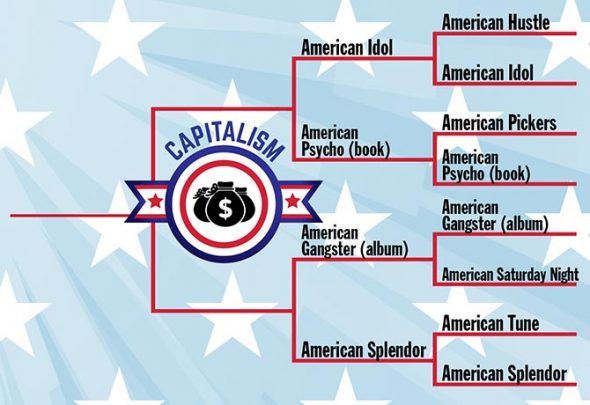

At least part of the fierceness of the competition in the Capitalism bracket is due to the sheer variety of media. While many of the other corners of our ‘Merica Madness bracket are dominated by movies, our play-in round showcased the ways that different types media illuminate similar underlying themes and tensions in American capitalism. The full bracket features even more diversity, both in terms of type of media, and perspectives on capitalism. That said, as I weighed each pair, I found important thematic resonances within each match-up, and will zoom in on those similarities as well as the differences as I decide the winners. Here’s what what our full bracket for the day looks like:

American Hustle vs American Idol

At first glance, American Hustle’s fictionalized account of a con man’s role in the FBI’s 1970s Abscam Operation and American Idol‘s early-oughts reality singing competition juggernaut have very little to do with each other. But viewed side-by-side, they both reveal something fundamental that punctures the often unshakable American faith in the free market: markets fail, and when they do, there are always individuals who are waiting, ready to take advantage of these inefficiencies.

David O. Russell’s 2013 film American Hustle focuses on two small time New York con artists Irving Rosenfeld and Sydney Prosser (played by Amy Adams and a very un-Bateman-like Christian Bale) who get caught by the FBI and yolked into helping the bureau entrap a variety of politicians in a corruption scandal. At a first pass, the connection between con artistry and capitalism is simple. Capitalism creates incentives to accumulate wealth by any means necessary, and the greediest individuals will pursue their own personal gain by taking advantage of others.

But as depicted in American Hustle, the connection between capitalism and con artists runs even deeper than greed. The initial scam that Irving and Sydney run is a fake loan, where marks give them a modest amount of money, in expectation of getting a much larger loan later (which of course never materializes). This con is based on a major feature of many market exchanges that involve a delay between payment and delivery: the buyer can’t necessarily observe the seller’s effort and intention. As Nobel Prize-winning Economist Douglass North pointed out, this kind of principal-agent problem is a common feature of markets, and is a major reason why third party enforcement of contracts by the government is a cornerstone of a well-functioning market. But as American Hustle shows in its latter half, governments are just as prone to principal-agent problems, in which politicians and bureaucrats use a lack of transparency and oversight to engage in economic activities that send direct benefits to themselves. This set of government failures enable the other two main cons in the film- the fake investment scheme that the con artists and their FBI contact Richie DiMaso use to set a bribery trap for a number of national legislators, and the final reversal that the two con artists pull on the FBI.

Although American Hustle does serve as a nice primer on the institutional economics of con artistry and corruption, it is also a David O. Russell film. This means that the same information asymmetries that enable the many cons to be set in motion are also used as a space for reinvention and self-actualization for the film’s protagonists. For all of the main characters, inventing fake identities and businesses isn’t just about economic gain, it is a chance to create a new identity.

And yet, for all of American Hustle’s dissection of the layers of misinformation and reinvention that enable con artistry to be part of American capitalism, American Idol may be an even more striking treatise on the same subject. At its core, Idol and other singing competition shows are also built on the premise that the music industry is also filled with the kinds of information asymmetries that the con artists in American Hustle exploit. In particular, the show is based on the idea that the tools that music executives have to identify new pop stars are limited, and that the way to solve those market failures (and identify a robust new cohort of pop stars) is to hold mass public auditions for a set of industry insiders, followed by round-after-grueling round of fan-voting to winnow the field down to a single winner, and to record and televise the whole thing. While Idol did generate its share of stars (Kelly Clarkson, Carrie Underwood, Chris Daughtry, and Jennifer Hudson), its bigger success was as a TV show. For the better part of the 2000s, Idol dominated TV ratings, with relatively little evidence that the contestants who were being selected as the winner each year were actually having any traction in the world of pop music. Now that is a scam that any con artist would have loved to have orchestrated.

Winner: American Idol

American Pickers vs American Psycho (Book)

Again, the surface similarities between American Pickers and American Psycho are pretty thin. To my knowledge, there have been no horrific murders in the 203 total episodes of the History channel antique-hunting reality show. (Although, I haven’t seen every episode of the series, so if there is an episode where head picker Mike Wolfe drops a chainsaw down a flight of stairs onto a fleeing woman, let me know in the comments). In addition, the setting of the two properties couldn’t be more different. Wolfe and his pickin’ partner Frank Fritz generally traverse the backroads of America’s rural heartland in their quest for buried gems. In contrast, Patrick Bateman inhabits only the highest points of 1980s Manhattan’s elite neighborhoods- Wall Street investment banks, Upper West Side Apartments, and SoHo and Chelsea restaurants and nightclubs.

Despite these differences, Pickers and Psycho are united on two fronts- their intense fetishization of consumer products and their depiction of the subtle modes of exploitation that take place when market changes are coupled with inequalities in power. These themes are relatively easy to spot in the American Psycho novel. As noted in Monday’s play-in round, the novel foregrounds Bateman’s fixation on designer brands and high end consumer products. In many cases these products are valuable to Bateman because he uses them in a nonstop (and unwinnable) internalized contest to measure himself against every one he meets in terms of status, taste, and wealth. At one point he scoffs at a video store clerk because she is wearing shoes with no discernable brand, and in another, he makes it his mission to emotionally break down an acquaintance who dared brag about having an Aiwa stereo (Sample diss: “Sansui is really top of the line. I should know. I own one.”) This constant mode of market transaction as a dominance feeds into many of his earliest violent acts that he describes to us- he lords money over a homeless man before brutally stabbing him in the eye; he offers a sex worker a paycheck she can’t refuse before visiting horrible violence upon her. By viewing all social interactions through the lens of consumer acquisition, Bateman has lost something fundamental about his humanity.

Take away the horrific violence, and these dynamics of obsession over consumer products and exploitative economic relationships are also present in American Pickers. The core premise of Pickers is essentially Antiques Roadshow meets Indiana Jones. Each episode follows antiques scavengers Mike Wolfe and Frank Fritz as they follow leads to barns, sheds, and attics that are filled with junk. In each episode, Wolfe and Fritz rifle through the piles of junk alongside the (almost always extensively bearded) owner in search of rare products that can be sold at a mark-up in their own antiques stores. As a result, an episode of American Pickers is filled with nearly as much brand-based name dropping as any given chapter of American Psycho, albeit with a focus on classic cars, motorcycles, and toys instead of high end suits and stereos.

Once Wolfe and Fritz find a set of items they like, they negotiate with the owner over the selling point, trying to drive a bargain that the owner will accept, but which gives them large enough margins to refurbish the item and still be able to sell it for a profit. While the edited negotiations and voice overs typically paint a narrative of everyone feeling good about the transaction, it is hard not to see a subtle power dynamic at play in these interactions. The pickers come to sellers with superior resources, knowledge about market prices, and the benefit of having a TV production crew to put a little extra pressure on unwilling sellers.

Obviously, the exploitation hovering around the edges of American Pickers is nowhere near as horrific as what is depicted in American Psycho. And maybe that’s exactly where it falls short. This is not to say that I wish that Wolfe and Fritz were psychotic drifters, traveling the plains, murdering hoarders and stealing their antiques (although let’s be honest, I’d probably watch that show too). But it is possible that the conventions of the conventional reality show format may obscure some of what is most interesting about Pickers. While Wolfe and Fritz seem like genuinely good guys who do really care a lot about the stories of the products they purchase and the wellbeing of their sellers, I also imagine that there are a lot of elements of the picking business that are much more unsavory, and I can’t help but wish for the novel, documentary, or TV drama that unpacks some of those dynamics.

Winner: American Psycho (Book)

American Gangster (Album) vs “American Saturday Night”

Jay-Z’s American Gangster album and Brad Paisley’s song “American Saturday Night” are unique in this week’s set of matchups in that they are both pieces of music (as opposed to our other pairings: movie vs. reality TV show, postmodern novel vs. reality TV show, song vs. postmodern comic book movie). However, just because we’re contrasting two pieces of music doesn’t mean that they have a lot in common thematically. In many ways, Jay-Z’s concept album about creating economic opportunities through the drug trade and Brad Paisley’s pop-country ode to the American melting pot are further from each other thematically than any other two matchups in the Capitalism bracket.

In order to get some traction on which of these two very different pieces of music better illuminate a crucial element of American capitalism, it is worth digging into what “American” means in the context of each work. As discussed in Monday’s piece, in Jay-Z’s album, the characteristic “American-ness” is rooted in creating economic opportunities by any means necessary (even if they are illegal) in response to economic and racial inequality. To put a finer point on it, part of the album’s central argument is that a turn to illegal economic activity (and a mindset of “gangsterism”) is precisely an outgrowth of a lack of other opportunities. This is summed up well in the album’s third track, “American Dreamin’,” in which Jay-Z raps: “Seems as our plans to get a grant/Then go off to college, didn’t pan or even out” and later “Mama forgive me, should be thinking about Harvard/But that’s too far away.” From this recognition of a lack of opportunities for social mobility, the song moves immediately into problem solving mode, essentially putting Jay-Z in CEO mode, drafting his business plan for selling drugs, getting specific with challenges that face any entrepreneur- finding a supply of the product, identifying a market, and managing personnel. This level of specificity about the nitty gritty of the business strategy of Jay-Z’s illicit drug business hammers home the points about college from earlier in the song. These are obviously the skills necessary to succeed in any business, but due to limited economic opportunities, not just any business was necessarily on the table.

In contrast, “American Saturday Night” highlights multiculturalism as the defining virtue of “American” society. To quote the first verse and chorus:

She’s got Brazilian leather boots on the pedal of her German car

Listening to The Beatles singing “Back in the USSR”

Yeah, she’s going around the world tonight, but she ain’t leaving here

She’s just going to meet her boyfriend down at the street fairAnd it’s a French kiss, Italian ice

Spanish moss in the moonlight

Just another American Saturday night

Given current discourses around what it means to be “American” that have a much more exclusionary bent, this ode to how immigrants (and their ideas, products, and cultures) have shaped the core of who we are is refreshing. But what exactly does it have to do with capitalism? While most of the other entries in the Capitalism bracket have focused on dynamics associated with the domestic market, “American Saturday Night” is more outwardly focused on how free trade of people, products, ideas, and culture has shaped American capitalism. What the song does well is identify the broad range of international influences from many different countries, which taken together as a whole somehow feel quintessentially American.

Where the “American Saturday Night” falls short is in articulating why this free trade across borders is a good thing. The closest it comes is in the bridge, where Paisley sings,

You know everywhere has something they’re known for/

Although usually it washes up on our shores/

My great-great-great-granddaddy stepped off of that ship/

I bet he never ever dreamed we’d have all this

This starts to hint that Paisley’s vision of why an “American Saturday Night” is so great is that the open movement of people and ideas into the US is exactly what spurs innovation, dynamism, and and economic mobility. And yet, I’m left wanting a third verse that cashes it all out and shows a little bit of this dynamism in action, with a bit more specificity in detail. While Paisely does a good job of painting a picture of the many people and products that are part of the fabric of American economic life, he still isn’t able to totally put a finger on what they actually do.

Winner: American Gangster (Album)

“American Tune” vs American Splendor

Our final showdown of Paul Simon’s “American Tune” versus the film adaptation of Harvey Pekar’s autobiographical comic book series American Splendor requires very few imaginative contortions to see the parallels between the two pieces. Both the song and the film have striking similarities in tone and an overall bleakness of outlook regarding the effects of capitalism on individual happiness and self-actualization. Both the speaker in Paul Simon’s song and Harvey Pekar have wound up on the losing end of the American Dream, and are broken down by the drudgery of work-a-day life. In fact, I could actually easily imagine a supercut of clips from American Splendor set to the Paul Simon song. It would work perfectly and would be depressing as all hell.

As much as I’d like to send both of these entries on to the next round, arm-in-arm to take on Jay-Z, there has to be one winner (I begged and begged ‘Merica Madness tournament commissioner Matt Belinkie to make an exception, and he wouldn’t budge). As a result, picking a winner of this showdown will require digging past the similarities between the song and the film.

“American Tune”excels at painting a picture of unease, while gradually revealing the economic roots of the speaker’s distress. The first verse opens with references to a general sense of disorientation and exploitation, before reassuring the listener “But I’m all right, I’m all right/ I’m just weary to my bones”. Although the claim of being “All right” returns again and again throughout the song, these assurances are a bit less believable every time they are repeated. The second verse starts by showing that the speaker’s malaise is general: “And I don’t know a soul who’s not been battered/ I don’t have a friend who feels at ease/I don’t know a dream that’s not been shattered/Or driven to its knees.” The third verse (which functions more as a bridge) offers the tiniest sliver of hope in the image of a dream of taking flight and alongside the Statue of Liberty. However, this hopeful image, along with the “American Tune” of optimism comes crashing down in the last verse, closing on the thought that “You can’t be forever blessed/Still, Tomorrow’s going to be another working day/And I’m trying to get some rest.” This juxtaposition of the practical need for sleep to enable work is a sharp contrast with the emancipatory image of the dream. There is very little time for American Dreamin’ when you have a grueling work day in front of you every day until you die.

Like “American Tune,” American Splendor also focuses on the grinding bleakness associated with working a job that pays the bills, but provides little in the way of fulfillment or satisfaction. However, it turns the structure of “American Tune” almost completely on its head. The film starts with Harvey Pekar as a dissatisfied malcontent, both in a flashback to his childhood, and as an adult on the precipice of a second divorce, working a tedious job as a file clerk. When we meet Harvey (both as portrayed by Paul Giamatti, and as the real Harvey who shows up from time-to-time in the film), we very quickly get the sense is that he isn’t someone who would ever say “I’m all right/I’m all right”. And yet, despite Pekar’s crushing pessimism, by becoming a DIY comics author and publisher, he actually manages to find a way to break the cycle of labor and alienation depicted in “American Tune” and find a path to a kind of “All Right”. American Splendor is far from a Horatio Alger rags to riches story, and in fact, as depicted in the film, Pekar never quit his day job and kept working as a file clerk until retiring at the age of 61. But American Splendor also isn’t just a case of Pekar finding a hobby that makes the time between each work day bearable. Through the spread of American Splendor, Pekar became a kind of indie celebrity; let’s say the Ian MacKaye of comics. The increasing fame associated with the success of the American Splendor comics helped to supplement his income, but more importantly helped him forge social connections with R. Crumb and other artists, with his co-workers, and with the woman who would become his third wife and artistic collaborator. Pekar found a way to take the grinding alienation that Simon identified in “American Tune” and harnessed the power of indie commerce to realize a slightly less crushing version of the American Dream.

Winner: American Splendor

To recap, here’s what the Capitalism corner of our bracket looks like after today’s match-ups:

Next week, we start our “Sweet Sixteen” with the regional semi-finals for Violence and Sex on Tuesday and Family and Capitalism on Thursday.

Add a Comment