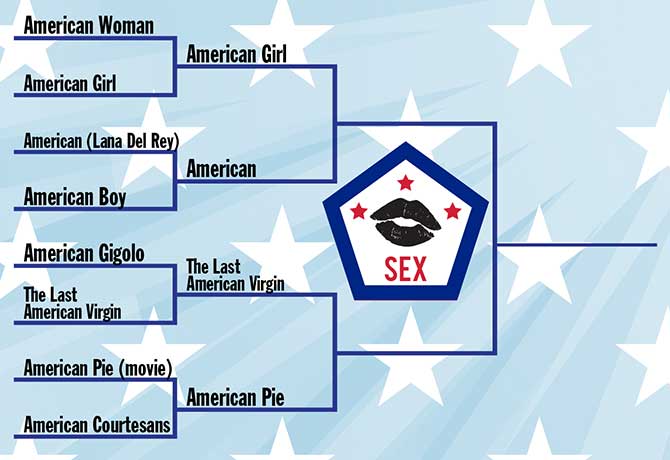

Overthinking It is celebrating our nation by searching for the most American piece of pop culture with the word “American” in the title. Read the entire series here.

hether we’re squirming, salivating, or twisting ourselves into knots over it, sex is part of what makes America ‘Merican. (Remember: you can’t spell ‘Merica without “I came.”) On the one hand, America was founded by Puritans. On the other hand, for a bunch of devout Christians, the Puritans were actually militantly sexual (advancing the doctrine that marital sex was a positive good rather than a necessary evil). And we’ve come a long way since then, as the Google image searches for “hot guy american flag thong” and “hot lady american flag bikini” will tell you. Note: exercise caution when clicking these links! First of all, they’re NSFW (obviously), second, apparently just anyone can go ahead and tag their own photo as “hot.”

hether we’re squirming, salivating, or twisting ourselves into knots over it, sex is part of what makes America ‘Merican. (Remember: you can’t spell ‘Merica without “I came.”) On the one hand, America was founded by Puritans. On the other hand, for a bunch of devout Christians, the Puritans were actually militantly sexual (advancing the doctrine that marital sex was a positive good rather than a necessary evil). And we’ve come a long way since then, as the Google image searches for “hot guy american flag thong” and “hot lady american flag bikini” will tell you. Note: exercise caution when clicking these links! First of all, they’re NSFW (obviously), second, apparently just anyone can go ahead and tag their own photo as “hot.”

Not just anyone can make sweeping judgments about entertainment, though. That’s our job. Ladies and gentlemen, these are the most ‘Merican pieces of pop culture about sex.

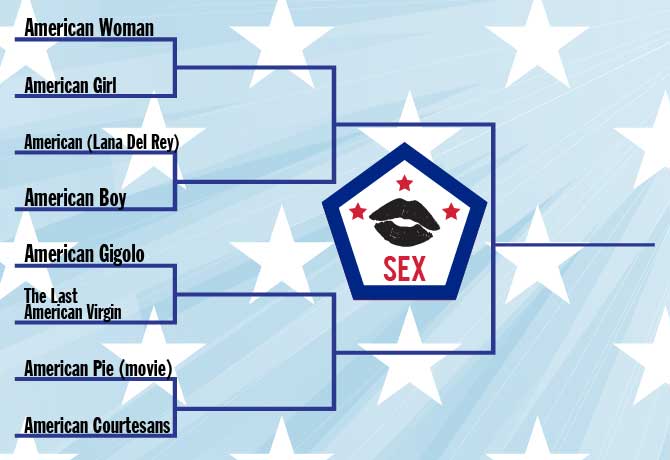

American Woman vs. American Girl

Our first matchup pits “American Woman,” by The Guess Who against “American Girl,” by Tom Petty. This no-holds-barred brawl will determine pop music’s most American take on the female gender! Unfortunately, for our purposes, we only care about the sexual aspects of that… and neither of the songs is very explicitly about sex. We kind of have to pretend that that’s what they’re about, and read the lyrics accordingly.

Our first matchup pits “American Woman,” by The Guess Who against “American Girl,” by Tom Petty. This no-holds-barred brawl will determine pop music’s most American take on the female gender! Unfortunately, for our purposes, we only care about the sexual aspects of that… and neither of the songs is very explicitly about sex. We kind of have to pretend that that’s what they’re about, and read the lyrics accordingly.

This is particularly difficult for “American Girl,” because most of the lyrics are about how she has, like, hopes and dreams and stuff. “She couldn’t help thinking that there / was a little more to life / somewhere else. /After all, it was a great big world.” (Yawnsville, am I right fellas? Fellas?)

The only really sexual part is the chorus.

Oh yeah, all right

take it easy baby

make it last all night

She was an American girl

I suppose there’s all kinds of things that you could be trying to make last all night. A pint of Ben & Jerry’s. Your dwindling supply of firewood, as the wolves circle ever closer. But the most natural interpretation of this line is sexual. The narrator of the song – presumably a guy, if we’re being heteronormative – is trying to draw out his encounter with the American girl as long as he possibly can. Which is a little jarring. Weren’t we just talking about her childhood? When did we end up in bed?

However we got there, the chorus of “Girl” paints an unlovely picture of American sexuality. Here’s what we learn:

- The average American sexual encounter is disappointingly short. (If they were already having satisfying sex, he wouldn’t be ordering her to prolong it.)

- The expectations that are being placed on American girls are wildly unrealistic. Make it last all night? Like, twelve-hours all night, sundown-to-sunup all night? Dude, even Sting was satisfied with just seven hours.

There’s one more important line to consider. At the end of the second verse, we find the girl reminiscing:

And for one desperate moment there

He crept back in her memory

God it’s so painful

Something that’s so close

And still so far out of reach.

There are a couple of ways to read this, but I think the most obvious one is:

- Even after twelve hours with the dude, she didn’t quite manage to climax. And years later, she’s still kind of pissed off about it. (I mean, I would be.) As we shall see, inadequacy turns out to be a recurring theme for this contest…

“American Woman” is famously a song about how, whatever an American woman is, this bunch of Canadians wants no part of her. As lyricist Burton Cummings put it, American women “seemed to get older quicker than our girls, and that made them, well, dangerous.”

“American Woman” is famously a song about how, whatever an American woman is, this bunch of Canadians wants no part of her. As lyricist Burton Cummings put it, American women “seemed to get older quicker than our girls, and that made them, well, dangerous.”

So what do The Guess Who actually have to say about the American woman? Well, they spend a lot of time telling her to leave. They don’t like the way that she tries to make herself pretty (“colored lights can hypnotize”), which implicitly calls for a more natural – and presumably Canadian? – type of beauty. It’s hard to know what to make of the “war machines/ghetto scenes” couplet, if we’re taking the song literally, but it probably means something similar: the American woman is technological, urban, and impoverished; the Canadian woman lives a life of agrarian rural leisure, Anne of Green Gables style. Finally, the problem with the American woman is that she’s too available. She keeps hangin’ around, keeps knockin’ around. The tag “no more” at the end of “don’t wanna see your face no more” is significant: it tells us that seeing her face has become habitual, and it’s a habit they’re trying to break.

Which of these songs gives the most ‘Merican account of female sexuality? Well, if you take a careful look at what we were able to draw out of “American Girl,” it turns out that the sexual stuff is actually mostly about the guy. His expectations, his desires, his shortcomings. I’m slightly tempted to say that a fundamental lack of interest in female sexuality IS the most American way to engage with female sexuality… but not that tempted. On the other hand, “American Woman” is probably not about American women at all. It came out in 1970: obviously, it’s a Vietnam protest song (as was legally required at the time). So neither contender looks particularly strong in this matchup.

As it turns out, the only way to arrive at a clear winner here is to view each song through the lens of male desire. (Overthinkingit.com: Part of the Problem™) If we do assume that “American Woman” is about a literal woman, it’s a song about how much the male narrator doesn’t want to sleep with her. In “American Girl,” on the other hand, the narrator definitely wants to sleep with her. I ask you: which of these is more ‘Merican? (While you ponder it, keep in mind that the American girl’s subjective experiences — what she cares about, what she wants out of life — only ever come up in the verses, while the narrator’s lust is confined to the chorus. ‘Merican doesn’t always mean good.)

Winner: American Girl

American vs. American Boy

And now we move on to the masculinity sub-bracket. The songs in this one are a lot more directly concerned with sex, or at least with the sexual suitability of their objects. (“American Boy” is about how great it would be to date Kanye West in the same sense that “Brown Eyed Girl” is about how great it was to date the brown eyed girl, and “Whatta Man” is about how great it is to date someone with a body like Arnold and a Denzel face.)

“American Boy” is very outward-looking: we learn hardly anything about the singer, although we can deduce that she’s interested in travel and fashion (and peen). As for the guy, Estelle describes him as charming and a snappy dresser, and we get a fair amount of specific detail about both of these things. Plus, he can take her on exciting vacations. These are all objectively good things! But this means that there’s nothing unusual about finding them attractive. And so there’s nothing confessional about the song at all: she could just as well be talking him up to a friend. It’s a materialistic account of romance — in the technical philosophical sense that it’s about tangible objects, not invisible essences. (The song is also pretty materialistic in the usual sense though.)

“American Boy” is very outward-looking: we learn hardly anything about the singer, although we can deduce that she’s interested in travel and fashion (and peen). As for the guy, Estelle describes him as charming and a snappy dresser, and we get a fair amount of specific detail about both of these things. Plus, he can take her on exciting vacations. These are all objectively good things! But this means that there’s nothing unusual about finding them attractive. And so there’s nothing confessional about the song at all: she could just as well be talking him up to a friend. It’s a materialistic account of romance — in the technical philosophical sense that it’s about tangible objects, not invisible essences. (The song is also pretty materialistic in the usual sense though.)

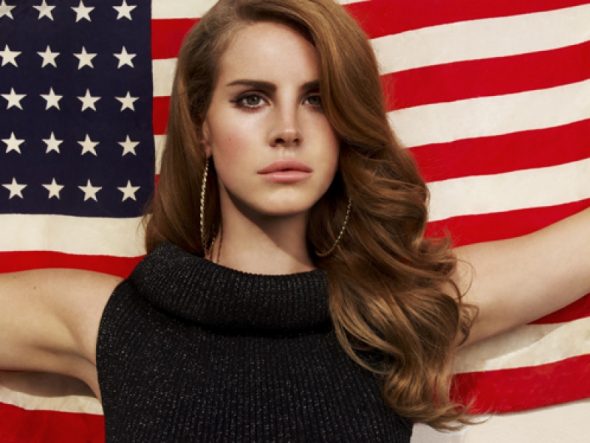

“American” is a very different beast. This time, the guy is a relative cipher: we know is that he’s tall, tan/gold/brown, and has good taste in old music, and that’s about it. What matters, though, is the way he makes her feel. “You make me crazy, you make me wild.” “Only you can take me there.” It’s that subjective experience, ultimately, that keeps her coming back: not what he is, but what he does to her. (A purely musical note: the surge in volume and the added layering of vocal echoes as the song moves into the pre-chorus — the “you make me crazy, you make me wild” part — neatly captures the well-nigh psychotropic rush of being around a person that you have a really brutal crush on.)

“American” is a very different beast. This time, the guy is a relative cipher: we know is that he’s tall, tan/gold/brown, and has good taste in old music, and that’s about it. What matters, though, is the way he makes her feel. “You make me crazy, you make me wild.” “Only you can take me there.” It’s that subjective experience, ultimately, that keeps her coming back: not what he is, but what he does to her. (A purely musical note: the surge in volume and the added layering of vocal echoes as the song moves into the pre-chorus — the “you make me crazy, you make me wild” part — neatly captures the well-nigh psychotropic rush of being around a person that you have a really brutal crush on.)

The “American” part of the lyrics is very oblique. It’s all one run-on sentence, starting here:

You make me crazy, you make me wild

Just like a baby, spin me round like a child

Your skin so golden brown

Be young be dope be proud

Like an American.

Who’s like an American, now? The only way to make grammatical sense of it is to reduce it to “You make me… be young, be dope, be proud,” in which case it’s her. If it’s him, you end up with “You… be young, etc.,” which is a barbarism, but it’s not like pop lyrics have to by grammatically correct, and that part of the lyric (starting with the “skin” line) seems more closely focused on the guy. I think this ambiguity is intentional: he is American, therefore she is American (and young, dope, etc.) when she’s around him.

So which is the most American concept of a sexually attractive man? I mean, I guess it can be two things: actual attraction is probably a mix of concrete material traits and inscrutable spiritual essence. But if we have to pick just one, the laurels go to “American.” Our pop culture is gradually getting more comfortable with the idea of objectifying men, but there’s still a gendered cultural model of desire in which the man is supposed to be attracted to the woman, and the woman is supposed to be attracted to the fantasy of being attractive for the man. Also, I don’t think that America as a nation is ready for a world in which guys are openly judged for their fashion choices.

Winner: American

American Gigolo vs. The Last American Virgin

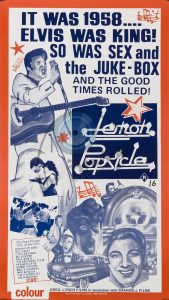

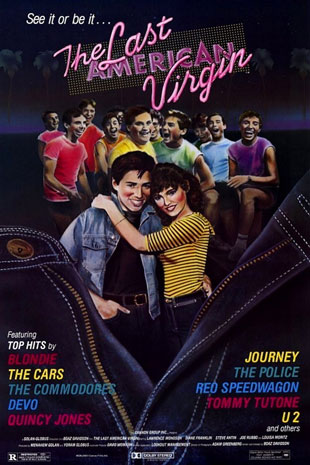

The Last American Virgin has one strike against it right off the block. Not because it’s another product by non-Americans – in this case, the Israeli production house Golan-Globus, which also produced American Ninja – but because it’s a remake of an absolutely iconic Israeli sex comedy called Eskimo Limon (aka Lemon Popsicle). If “American” means anything at all, it’s as a contrast to other national categories. Thus, if Eskimo Limon is really central to Israel’s concept of sex (and they did make eight sequels), it’s hard to see how its remake could be the most American treatment of anything.

The Last American Virgin has one strike against it right off the block. Not because it’s another product by non-Americans – in this case, the Israeli production house Golan-Globus, which also produced American Ninja – but because it’s a remake of an absolutely iconic Israeli sex comedy called Eskimo Limon (aka Lemon Popsicle). If “American” means anything at all, it’s as a contrast to other national categories. Thus, if Eskimo Limon is really central to Israel’s concept of sex (and they did make eight sequels), it’s hard to see how its remake could be the most American treatment of anything.

Nevertheless, if you are a scholar of the teen sex comedy genre, you have GOT to watch The Last American Virgin. (As a film it’s pretty well shite, but it’s a goldmine for gifs.) Tell me that this doesn’t say something profound about America:

What’s revealing here is that the making-out girl gets pushed up against the couch girl, while the popcorn guy stares wistfully at the making-out guy. We’ve talked before on this website about homosociality: a kind of sexual economy in which the woman is the medium of exchange (or possibly just the venue) for an erotic or romantic transaction between two men. The Last American Virgin has got to be the homosocialest movie of all time. The kernel of the plot is a love triangle involving the two close male friends and the new girl in town (which is already pretty suspicious). Then, on not one but TWO separate occasions, the two boys and their comic-relief fat friend line up to take turns doinking a promiscuous older woman. And to top it all off, of course – don’t go clicking this link, now — there’s the literal dick-measuring contest, which envisions American sexuality as a parade of hopeful erections. I told you not to click! Now look what you did.

Last Virgin’s model of sexuality is exclusively male (which is regrettable, but not — alas — particularly un-American), and to the degree that female sexuality exists in this film at all, it’s supposed to be scary. Here’s a short list of the things that the boys get from their erotic entanglements with women:

- humiliated in front of their parents

- pubic lice

- existential dread

- chased by an angry sailor

- pregnancy scares

- heartbreak

- brutal shoe beatings

This sense that women are an outright danger is kind of a new take on the classic homosocial narrative. If the classic model can be pictured as two men leisurely passing a cigar back and forth, the Last Virgin model is more like a game of hot potato. Except that one of the guys is like “no: give ME the hot potato. I want it to burn me. In the purging fires of its heat I will prove my love!” And the other guy is a lot more charming and good looking, and abandons the potato as soon as he gets in its pants. (Maybe this isn’t actually a good metaphor.)

Last Virgin’s first-round opponent is American Gigolo. This is a case where, in order to understand the “American-ness,” it’s really helpful to look at the title. The key is that “gigolo” is not quite an American word. Gigolo implies Italy, which implies Europe. We’re meant to find the idea of an American gigolo surprising and incongruous. (“American Rent Boy” would be quite another movie.) And so, as we wend our way through the film’s sexual underworld — from a porch full of topless sunbathers, to a swinger’s bedroom, to the amyl-nitrate-fueled dancefloor of a nightclub – there’s always a whiff of pearl-clutching moral outrage hovering right beneath the surface. “This might be how Europeans run their lives,” we think, “but it’ll never fly here. We’re Americans, thank you very much: we treat sex with the existential dread it deserves.”

Last Virgin’s first-round opponent is American Gigolo. This is a case where, in order to understand the “American-ness,” it’s really helpful to look at the title. The key is that “gigolo” is not quite an American word. Gigolo implies Italy, which implies Europe. We’re meant to find the idea of an American gigolo surprising and incongruous. (“American Rent Boy” would be quite another movie.) And so, as we wend our way through the film’s sexual underworld — from a porch full of topless sunbathers, to a swinger’s bedroom, to the amyl-nitrate-fueled dancefloor of a nightclub – there’s always a whiff of pearl-clutching moral outrage hovering right beneath the surface. “This might be how Europeans run their lives,” we think, “but it’ll never fly here. We’re Americans, thank you very much: we treat sex with the existential dread it deserves.”

American Gigolo does have a model of “good sex,” which is when a man and a woman are deeply in love, and she does stuff to make him feel good in the bedroom. The titular gigolo, Julian (played by Richard Gere at peak hotness) prides himself on his technique in the bedroom, and works really hard to make sure that the women he sleeps with are having a good time. For the film, this is proof that he’s broken and in dire need of redemption. And at least the bad sex that he was having was vanilla p-in-v stuff! If Last Virgin is a little scared of women, Gigolo is absolutely terrified of homosexuality. The film’s twisty plot is all about Julian getting framed for murder by one of his pimps, Leon. When he figures out what’s going on, Julian breaks down and begs Leon to tell the police that he’s innocent. “I’ll do anything! I’ll do gay! I’ll do kink!” For this line to land the way the screenwriter wanted it to, I’m pretty sure the audience’s reaction has to be “Ew, gay!” The film never even really bothers to establish that Leon is evil. The fact that he’s gay is supposed to be the shocking revelation.

American Gigolo does have a model of “good sex,” which is when a man and a woman are deeply in love, and she does stuff to make him feel good in the bedroom. The titular gigolo, Julian (played by Richard Gere at peak hotness) prides himself on his technique in the bedroom, and works really hard to make sure that the women he sleeps with are having a good time. For the film, this is proof that he’s broken and in dire need of redemption. And at least the bad sex that he was having was vanilla p-in-v stuff! If Last Virgin is a little scared of women, Gigolo is absolutely terrified of homosexuality. The film’s twisty plot is all about Julian getting framed for murder by one of his pimps, Leon. When he figures out what’s going on, Julian breaks down and begs Leon to tell the police that he’s innocent. “I’ll do anything! I’ll do gay! I’ll do kink!” For this line to land the way the screenwriter wanted it to, I’m pretty sure the audience’s reaction has to be “Ew, gay!” The film never even really bothers to establish that Leon is evil. The fact that he’s gay is supposed to be the shocking revelation.

But all the stuff that American Gigolo finds horrifying feels decidedly tame by 2016 standards. Like, I listen to Dan Savage’s podcast: there was a call a few months back where a woman asked for detailed technical advice about preventing her husband’s [bleep] from slipping out of her [bloop] during intercourse, and NEITHER OF THOSE CENSORED WORDS ARE THE ONES YOU’RE PROBABLY THINKING ABOUT. She was totally blasé about this, and so was Dan. It’s not like she and her husband were staring into the abyss of flesh: for them, this was a typical Saturday. And now I’m supposed to be horrified because the American Gigolo sends the camera on a stroll through a gay club on leather night?

Structurally, this scene is supposed to be about as low as Julian ever gets. Real belly-of-the-whale stuff. But what was supposed to play as “Ooh, menacing gay people! How gritty!” actually plays as “Gay people have cool parties; also, nothing happens in this scene.” Protip: if you want Hell to feel unappealing, get someone other than Giorgio flippin’ Moroder to do the soundtrack. (Here’s a link to “I Feel Love,” the second massive hit Moroder created for Donna Summer. Not because it’s relevant or anything, just because I like you and I want you to be happy.)

Anyway, I’m very glad to report that the structural homophobia that American Gigolo is built around no longer feels American at all. You should for sure watch it: it’s so pretty to look at — did you see that color balance, though? — and Moroder is a disco god. But if it was ever ‘Merican, that time has past.

Winner: The Last American Virgin

American Pie vs. American Courtesans

I probably don’t need to explain a lot about American Pie. It’s the one where Jason Biggs f__ks the pie, remember? Where a horny high school boy — hornier than most, perhaps, but still a recognizable member of his genus — is so desperate to know what sex feels like that he uses his dingus as a cake tester.

I probably don’t need to explain a lot about American Pie. It’s the one where Jason Biggs f__ks the pie, remember? Where a horny high school boy — hornier than most, perhaps, but still a recognizable member of his genus — is so desperate to know what sex feels like that he uses his dingus as a cake tester.

And that’s really all you need to know about it. I mean, sure, the plot, four guys try to have sex before prom night, who cares. Here is American Pie’s thesis about American sexuality: WAAAAAAANT! CAAANNOOTT HAAAAVE!

Because American Pie is not really about sex. American Pie is about desire, humiliation, and the idea that desire causes humiliation. Whether it’s Oz getting mocked by Stifler for his sensitive-guy feelings, or Jim going off half-cocked (as it were) with Nadia, trying to have sex only ever ends in shame. The very experience of desire makes you worthless and unf__kable. The only way to achieve sex is to stop wanting sex: ask the band geek to the prom, tell your girlfriend that you respect her boundaries, etc., at which point, like some sort of blueballed arhat, you’re immediately whisked away to the promised land. Does this make any sense? No. But look at all the guys who already ARE having sex. Do they walk around all day drowning in the ferment of their own rancid lust? Surely not: they’re having sex. So you can see how a person might get confused.

As in Last Virgin, this is an exclusively male picture of sexuality. I’m not saying that women don’t deal with a similar bind: the point is that the movie doesn’t care. Women, in American Pie, are overflowing vessels of sex. They might want or not want to have sex at any particular time, but a woman losing her god-damned mind over sex the way all the men do is as nonsensical as water getting thirsty.

By the way: I could write a whole other article about everything that’s wrong with the “warm apple pie line,” but I’ll limit myself to one: is Oz suggesting that vaginas have, like… chunks? (Whatever, he’s supposed to be a stupid teenager, this is immaterial.)

Facing off against Pie is American Courtesans, which is probably the most obscure contestant in this division. (It’s a documentary, what are you gonna do?) For the most part, Courtesans consists of talking head interviews with sex workers, livened up with a dash of the ol’ Ken Burns pan & scan. Visually, it’s real Documentary-101 stuff. But as is often the case, the film rises and falls on the humanity of its subjects and the importance of the social issue that it addresses. And on this front, it’s pretty great.

Facing off against Pie is American Courtesans, which is probably the most obscure contestant in this division. (It’s a documentary, what are you gonna do?) For the most part, Courtesans consists of talking head interviews with sex workers, livened up with a dash of the ol’ Ken Burns pan & scan. Visually, it’s real Documentary-101 stuff. But as is often the case, the film rises and falls on the humanity of its subjects and the importance of the social issue that it addresses. And on this front, it’s pretty great.

Where Pie reduces women to vagina-havers, the whole thesis of Courtesans is that its subjects are more than that. Their stories are compelling, unguarded, and occasionally brutal… and very far from sexy. These women aren’t against sex, mind you, and several of them speak warmly about the physical aspect of their job. But they seem to see it as a kind of affective labor, analogous with childcare, geriatric care, nursing, and the like. They take pride in helping their clients, but none of them seem excited by sex for its own sake.

So there’s desire in this movie, but not sexual desire: it’s desire for money, or power, or healing, or freedom. And sex can be all those things, of course… but try telling that to America! Our culture has always tried to pretend that sex is simultaneously A: the transcendent culmination of a deeply spiritual romance, B: a bit of harmless fun, and C: shameful and wrong. Which are pretty much the things that American Pie suggests sex is.

Next to Courtesans, Pie looks shallow. (Not to mention rapey. How that webcam scene made the final edit…) But at the end of the day, we’re faced with the question of which is more American: an unflinching look at the complex, sometimes grim, sometimes touching reality of a sex worker’s lived experience? Or the glitzy aura of desire that our culture projects over every sexually available female?

Yeah.

Winner: American Pie. And God have mercy on our souls.

Here’s how the bracket looks after round 2.

Next week, we’re going to try to keep things wholesome: what is the most American pop cultural depiction of family?

Your statement that “American Pie is not really about sex” makes me wonder if many of the movies that are supposedly about sex are actually about the issues surrounding sex. Hell, even sex in real life is often “about” other things, like power and control and status and loneliness, etc. Of course, I suppose if you’re going to play that game then no movie about an activity is really about that activity, it’s always about people and their desires. Bring It On isn’t about cheerleading, it’s about gender and race and leadership and friendship, etc. So ignore this whole paragraph.

I remember as a know-it-all teenager being sort of down on American Pie, because it seemed to shy away from a full-out embrace of sexuality into a slightly Puritanical, “sex isn’t all that important, you guys” type ending. Sort of the way Van Wilder (out three years later) had to end with a downer “partying isn’t the most important part of college, you guys” message. Compare that to Animal House or Porky’s (the gold standard for sex comedies as far as I’m concerned), in which the ending leans hard into joyous hedonism, not newfound maturity. I think it’s significant that the main character’s first sex partner, the infamous “one time at band camp” girl, isn’t just a crazy story but the love of his life. In American Pie, there is no such thing as casual sex.

“The expectations that are being placed on American girls are wildly unrealistic.”

Seriously, though.

As for American by Lana del Ray, I’ve apparently been willfully hearing the lyrics incorrectly for years. I’ve always heard it as “be young, be dull, but be proud.”

Also, thanks, Jordan. I like you too. Now excuse me while I go listen to Donna Summer for a couple of hours.

“be young, be dull, but be proud” would be a much more interesting lyric!

It seems like the four songs here mean very different things when they use that word “American”:

American Woman – sexually aggressive, dominant, kind of scary

American Girl – striving for a better life

American – hot, cool, reluctant to commit

American Boy – wealthy, capable of giving a foreign woman a lavish lifestyle

The cool thing is that all of these definitions seem to work!