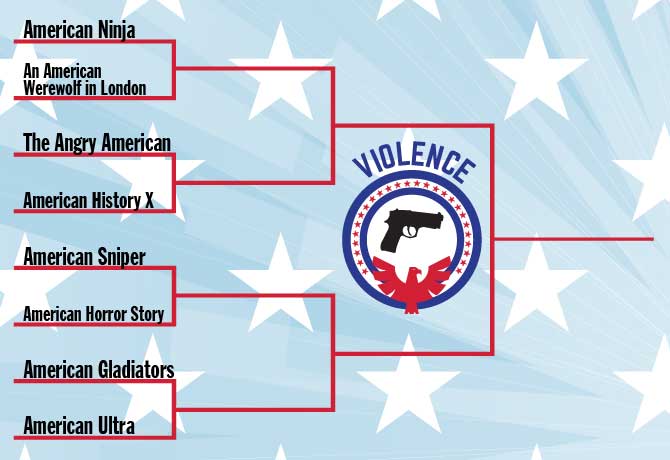

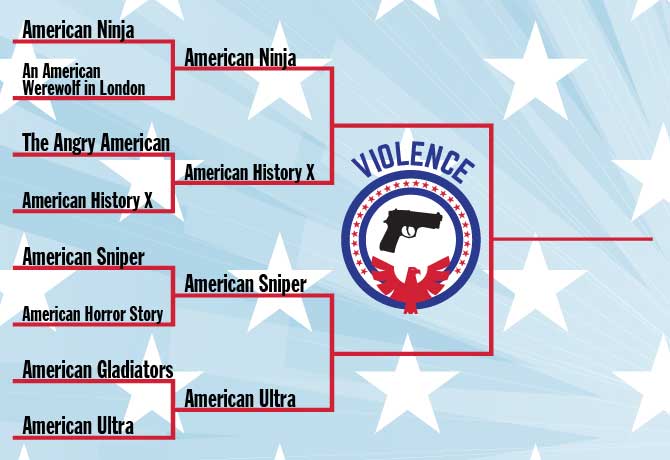

Overthinking It is celebrating our nation by searching for the most American piece of pop culture with the word “American” in the title. Read the entire series here.

he United States has been in love with violence since the very beginning. We aren’t unique in having won our freedom through arms, but we went one step further and enshrined our right to keep them for a well-regulated militia. In other words, we wanted to constitutionally ensure that we’d have the means to overthrow the government if we felt like it. The American ideal of rugged individualism has always gone hand in hand with a willingness to fight for it and defend it, to the point where aggression is seen as a core American value. Today, Americans are killed by firearms at a rate 25 times greater than the rest of the developed world, and while some of that is due to the massive amount of guns floating around, a lot of it has to do with our admiration for asskickers. Ladies and gentlemen, these are the Most ’Merican pieces of pop culture about Violence:

he United States has been in love with violence since the very beginning. We aren’t unique in having won our freedom through arms, but we went one step further and enshrined our right to keep them for a well-regulated militia. In other words, we wanted to constitutionally ensure that we’d have the means to overthrow the government if we felt like it. The American ideal of rugged individualism has always gone hand in hand with a willingness to fight for it and defend it, to the point where aggression is seen as a core American value. Today, Americans are killed by firearms at a rate 25 times greater than the rest of the developed world, and while some of that is due to the massive amount of guns floating around, a lot of it has to do with our admiration for asskickers. Ladies and gentlemen, these are the Most ’Merican pieces of pop culture about Violence:

American Sniper vs American Horror Story

Americans like to see themselves as masters of their own destinies, free to cast off old traditions and family bonds to craft new lives and identities. Being a sixth generation cobbler isn’t seen as admirable; Americans romanticize the idea of starting things with a clean slate.

American Horror Story says that nobody ever gets a clean slate. Everyone is tainted by the ugly history that came before us. It’s significant that in every season, there’s at least one episode that flashes back a generation or more to show the cyclical nature of violence. The longer the show goes on, the more we see dark connections between seemingly isolated incidents. Lady Gaga in Season 5 had a horrific illegal abortion at the house from Season 1. Jessica Lange from Season 4 was mutilated by the sadistic Nazi doctor from Season 2. Misery begets misery; monsters create monsters. At the end of each season, almost everyone is dead, but the same faces are back next season to enact another set of grisly tragedies. In America you can run, but when you carry the darkness inside you, there’s no place to hide.

American Horror Story says that nobody ever gets a clean slate. Everyone is tainted by the ugly history that came before us. It’s significant that in every season, there’s at least one episode that flashes back a generation or more to show the cyclical nature of violence. The longer the show goes on, the more we see dark connections between seemingly isolated incidents. Lady Gaga in Season 5 had a horrific illegal abortion at the house from Season 1. Jessica Lange from Season 4 was mutilated by the sadistic Nazi doctor from Season 2. Misery begets misery; monsters create monsters. At the end of each season, almost everyone is dead, but the same faces are back next season to enact another set of grisly tragedies. In America you can run, but when you carry the darkness inside you, there’s no place to hide.

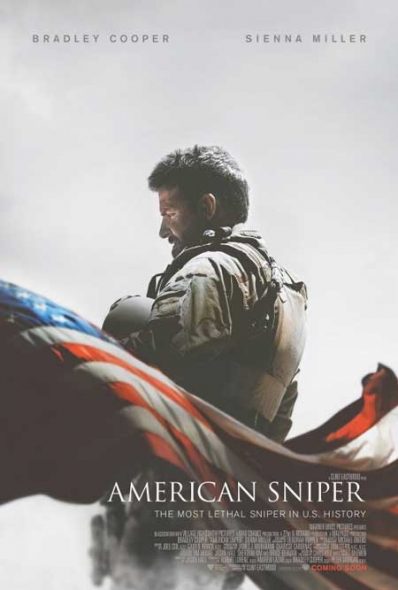

In American Sniper, violence is also a legacy that gets passed down, but it’s presented as a positive thing. “You have been blessed with the gift of aggression,” Chris Kyle’s father tells him, exhorting him to be a sheepdog, protecting the sheep from the wolves. So when Kyle (Bradley Cooper, all hulked out) sees footage of the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings on TV, he signs up for action. We see him save countless American marines with his infallible aim. We see him volunteer for more dangerous assignments when he feels like others are taking all the risk. We see him re-enlist again and again, even after his friends are killed and his wife threatens to leave him. He’s a hell of a sheepdog.

But the gift of aggression cuts both ways. When he’s back in the States, Kyle is jumpy, withdrawn, his blood pressure off the charts. He screams at the maternity ward nurses for not paying enough attention to his daughter. He almost kills the family pet with his bare hands. All his wife Taya wants from him is that he be a normal husband and father, but it’s like asking a sheepdog to become a sheep.

But the gift of aggression cuts both ways. When he’s back in the States, Kyle is jumpy, withdrawn, his blood pressure off the charts. He screams at the maternity ward nurses for not paying enough attention to his daughter. He almost kills the family pet with his bare hands. All his wife Taya wants from him is that he be a normal husband and father, but it’s like asking a sheepdog to become a sheep.

It’s only through working with other emotionally and physically scarred veterans that Kyle starts to regain some semblance of normality… right before a schizophrenic veteran kills him for no reason. It’s a shocking tragedy, but maybe the real shock would be if Kyle didn’t die a violent death. “You can only circle the flame so long,” Taya tells him at one point, but he doesn’t know how to stop.

Chris Kyle, like the misfits of American Horror Story, is changed and haunted by violence. But there’s a crucial difference: in AHS, the characters are mostly insane, selfish, or consumed by rage to the point where right and wrong don’t matter. To Kyle, right and wrong are everything. He’s taking on the burden of violence to protect others, at great personal cost. Nevermind whether Kyle’s worldview is woefully misguided; what matters here is that he believes he’s fighting for good, while the American Horror Story characters know they’re going straight to Hell. It’s that sense of righteous purpose that makes American Sniper the better depiction of our national gift/curse of aggression.

Winner: American Sniper

American Ninja vs An American Werewolf in London

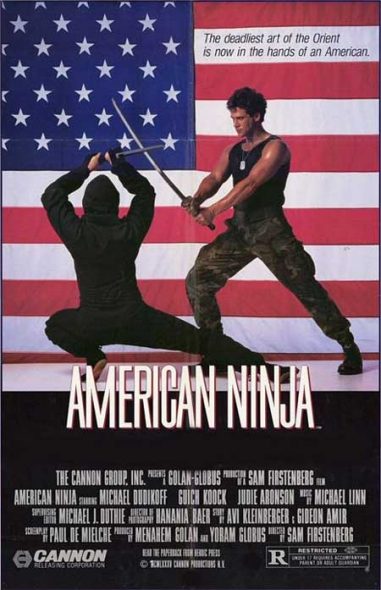

American Ninja is a product of legendary 1980s b-movie factory Cannon Films, headed by Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus. Just like Nabokov, these outsiders were able to perceive America more clearly than the Americans (we’ll talk about their work again when we get to Sex), and they saw that what audiences in the testosterone-fueled Reagan era wanted was American exceptionalism, and also ninjas with wrist-mounted laser guns.

On an island in the South Pacific, a French aristocrat is hijacking American military convoys using a private army of ninjas. But along comes a young American soldier named Joe Armstrong (played by Michael Dudikoff – extra points for the perfect 1980s action name). Joe turns out to be pretty good at ninjaing himself, when he’s not seducing the Colonel’s daughter.

On an island in the South Pacific, a French aristocrat is hijacking American military convoys using a private army of ninjas. But along comes a young American soldier named Joe Armstrong (played by Michael Dudikoff – extra points for the perfect 1980s action name). Joe turns out to be pretty good at ninjaing himself, when he’s not seducing the Colonel’s daughter.

This is a pretty old trope, the idea that Americans can easily surpass foreigners at whatever native skills they bother to learn, usually in a matter of months. It’s as old as The Last of the Mohicans and as popular as Avatar. And at a time when Japanese corporations were widely feared to be taking over America (remember Marty’s future boss in Back to the Future 2?) the idea of an American ninja was appealing enough to spawn three sequels (and that’s not including American Samurai).

Here’s another well-worn cliché: American tourists are a rowdy, disrespectful, downright dangerous plague. (Ryan Lochte is only the most recent example.) At first glance, An American Werewolf in London seems to play on this fear. David Kessler is an American teenager in Europe in search of adventure and girls. He ends up brutally killing scores of people before the police gun him down.

But David doesn’t start out as a monster. He just wanders into the wrong rural Scottish village, where the locals – rather than warning him that a werewolf is on the loose – tell him an anti-American joke. To make matters worse, once David gets bit the villagers just dump him in London, knowing that at the next full moon he’s going to kill. So the villain here isn’t Americanism; it’s the cowardice and insularity of the Old World. David’s actually a model American: polite, charming, and full of self-deprecating humor. But he’s in the wrong place at the wrong time on the wrong side of the world, swallowed up by forces he doesn’t understand and can’t control.

But David doesn’t start out as a monster. He just wanders into the wrong rural Scottish village, where the locals – rather than warning him that a werewolf is on the loose – tell him an anti-American joke. To make matters worse, once David gets bit the villagers just dump him in London, knowing that at the next full moon he’s going to kill. So the villain here isn’t Americanism; it’s the cowardice and insularity of the Old World. David’s actually a model American: polite, charming, and full of self-deprecating humor. But he’s in the wrong place at the wrong time on the wrong side of the world, swallowed up by forces he doesn’t understand and can’t control.

Both of these films are about the bloody clashes of a lone American and a foreign culture. In American Ninja, Joe’s combination of Japanese secrets and innate American awesomeness makes him both the best of all ninjas and the most deadly (and therefore the best) of all Americans. In An American Werewolf In London, David’s Americanness is a disastrous liability: he falls victim to a curse all the locals know how to avoid.

But what rubs me the wrong way about Werewolf is how innocent and helpless David seems. Historically, Americans are more often the perpetrators of cultural misunderstandings, not the victims of them (the classic 1958 novel The Ugly American popularized the titular phrase for arrogant, ethnocentric Yanks). Werewolf is a movie about how Americans abroad should be wary of foreign cultures, and Ninja is a movie about how foreign cultures should be wary of us, and I know which of those messages carries more historical weight. Also, how awesome a name is Michael Dudikoff?

Winner: American Ninja

American Gladiators vs American Ultra

Thirty-somethings, sing along with me: dum du-du da da DAAAA! Da da da da!

(Fun fact – the theme song was by Bill Conti, Mr. Gonna Fly Now himself.)

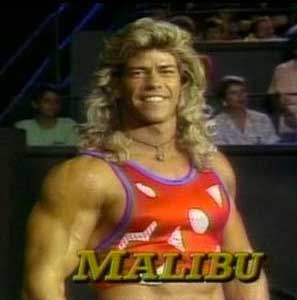

American Gladiators was an attempt to take the pageantry of pro wrestling and incorporate unscripted competition. The giant hamster balls might seem like harmless fun, but as Dan Clark (aka Nitro) wrote in his memoir, the Gladiators were not kidding around: “The whistle blows. I blast into my opponent with reckless abandon, instantly overwhelming and dominating him. My shoulder slams into his ribs, sending the ‘football captain’ flying in the air before landing in a painful, broken heap at my feet. The world slips away, and for a moment the voices are quiet. The universe is mine.” This is a show that was aired on weekend afternoons for kids.

American Gladiators was an attempt to take the pageantry of pro wrestling and incorporate unscripted competition. The giant hamster balls might seem like harmless fun, but as Dan Clark (aka Nitro) wrote in his memoir, the Gladiators were not kidding around: “The whistle blows. I blast into my opponent with reckless abandon, instantly overwhelming and dominating him. My shoulder slams into his ribs, sending the ‘football captain’ flying in the air before landing in a painful, broken heap at my feet. The world slips away, and for a moment the voices are quiet. The universe is mine.” This is a show that was aired on weekend afternoons for kids.

As beloved as the Gladiators were, the whole point of building them up was to then give us underdog challengers to root for. Americans like to think of themselves as the little guy, even though we’re the most powerful nation on Earth. Think about Rocky, the Miracle on Ice, and rags-to-riches stories from Horatio Alger to Steve Jobs. The fantasy of American Gladiators was going up against these larger-than-life figures and rising to the occasion.

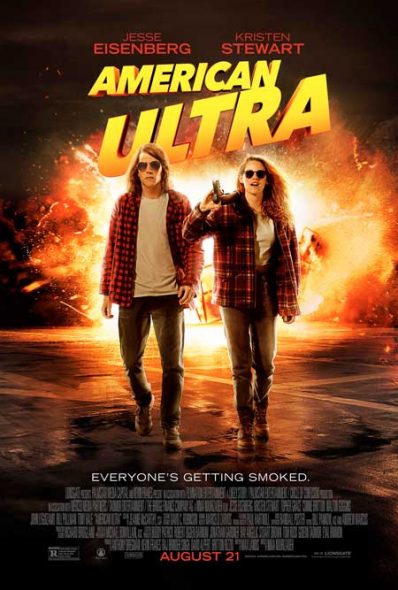

That’s also at the heart of American Ultra, which was a box office failure in 2015 but a really interesting entry into our bracket. Jesse Eisenberg plays Mike Howell, an utterly average stoner living in a run-down West Virginia town working at a convenience store. But Mike is actually a veteran of a secret government program, trained as an assassin and then implanted with false memories when the program was cancelled. When a CIA bureaucrat decides he needs to be killed off to clean up loose ends, Mike’s programming comes back and much bloodiness ensues.

Now technically Mike isn’t exactly an everyman, since he has years of government training at his disposal. But he certainly presents as a normal guy. After he dispatches the first two assassins, he calls his girlfriend in panic, babbling, “If you don’t come here right now, I’m just gonna start, like, pissing in my pants. I swear to God, Phoebe, I’m just gonna start, like, pissing.” And much like Bourne before him, he only has MacGuyvered weapons at his disposal while the government is calling in drone strikes, poison gas, and hit squads of dangerous mental patients. Much like in Gladiators, the satisfaction comes from seeing a regular Joe outbadassing the badasses to claim a better life for himself.

Now technically Mike isn’t exactly an everyman, since he has years of government training at his disposal. But he certainly presents as a normal guy. After he dispatches the first two assassins, he calls his girlfriend in panic, babbling, “If you don’t come here right now, I’m just gonna start, like, pissing in my pants. I swear to God, Phoebe, I’m just gonna start, like, pissing.” And much like Bourne before him, he only has MacGuyvered weapons at his disposal while the government is calling in drone strikes, poison gas, and hit squads of dangerous mental patients. Much like in Gladiators, the satisfaction comes from seeing a regular Joe outbadassing the badasses to claim a better life for himself.

But there’s a crucial difference. The people who competed on American Gladiators were amazing athletes, sometimes even Olympians, Heisman Trophy winners, or Ellen Degeneres one time. They were in the kind of peak physical condition that most of us can only dream of. Jesse Eisenberg, not so much. In fact, you’re pretty sure that you could take him out, if you really needed to. And by the transitive property of ass-kicking, that means you could easily beat up waves of government agents to save your girl. That’s as American as the Second Amendment, and it sends American Ultra to the next round.

Winner: American Ultra

Courtesy Of The Red, White And Blue (The Angry American) vs American History X

When Osama Bin Laden was killed in May 2011, Toby Keith’s “Courtesy Of The Red, White And Blue (The Angry American)” was suddenly in heavy rotation. “Hey Toby!!!!!” tweeted Blake Shelton. “We finally put the boot in that ass!!!!!” As fate would have it, Keith was actually on a USO tour in Iraq at the time. “It’s a great day to be an American,” he said. “I’ve been telling you for a decade that the U.S. military would hunt down and kill world enemy No. 1.”

But the song was never quite that specific. Sure, the most famous lyric can be interpreted as a threat towards Bin Laden: “And you’ll be sorry that you messed with the U.S. of A. / ‘Cause we’ll put a boot in your ass, it’s the American way.” But Keith never actually names Bin Laden, and at times the target of the boot seems to be much broader. “Soon as we could see clearly through our big black eye / man, we lit up your world like the 4th of July.” Bin Laden actually escaped into Pakistan after September 11th, so is Keith bragging that at least we carpet-bombed Afghanistan in retaliation? Or is the “your” not just one man but anyone in that part of the world? That’s what Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks thought about “The Angry American,” telling the Los Angeles Daily News, “It targets an entire culture – and not just the bad people who did bad things.”

But the song was never quite that specific. Sure, the most famous lyric can be interpreted as a threat towards Bin Laden: “And you’ll be sorry that you messed with the U.S. of A. / ‘Cause we’ll put a boot in your ass, it’s the American way.” But Keith never actually names Bin Laden, and at times the target of the boot seems to be much broader. “Soon as we could see clearly through our big black eye / man, we lit up your world like the 4th of July.” Bin Laden actually escaped into Pakistan after September 11th, so is Keith bragging that at least we carpet-bombed Afghanistan in retaliation? Or is the “your” not just one man but anyone in that part of the world? That’s what Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks thought about “The Angry American,” telling the Los Angeles Daily News, “It targets an entire culture – and not just the bad people who did bad things.”

Toby Keith is by no means equivalent to the neo-Nazis in American History X (I’m uncomfortable even putting them in the same sentence), but the common thread that connects the song and the movie is a national tendency to paint with a broad brush. “I hate anyone that isn’t a white Protestant,” says teenaged Danny Vinyard.

Toby Keith is by no means equivalent to the neo-Nazis in American History X (I’m uncomfortable even putting them in the same sentence), but the common thread that connects the song and the movie is a national tendency to paint with a broad brush. “I hate anyone that isn’t a white Protestant,” says teenaged Danny Vinyard.

Danny Vinyard: They’re a burden to the advancement of the white race. Some of them are alright I guess…

Seth: None of them are fucking alright Danny, okay? They’re all a bunch of fuckin’ freeloaders. Remember what Cam said: we don’t know ’em, we don’t wanna know ’em.

That’s a great bit of double-think there: complete certainty that he understands the Other combined with complete unwillingness to learn anything about him. It’s the same attitude that got us slavery, the Trail of Tears, internment camps, and “Build That Wall.”

“The Angry American” is a good example of how tragedy can become generalized into a justification for almost anything. (Researching the song, I found a reference to Keith visiting the infamous Abu Ghraib prison in the middle of the torture scandal. This was literally a case where America put things in people’s asses.) However, American History X goes further to show exactly how difficult it is to climb back up that slippery slope. Edward Norton only rejects his racist ideology after being locked up with the most good-natured black guy in the country, and even then he can’t do anything to break the cycle of violence. The movie can be painfully unsubtle (YOU SHOT IT IN BLACK AND WHITE, I GET IT) but it also seems as sadly relevant today as it did 18 years ago; the alt-right is all over the news as I type this.

Sorry Toby: you’ve been out-angered.

Winner: American History X

Here’s how the bracket looks like after Round 1.

Next week, let’s talk about sex, baby.

Aww man, I only matched 1 out of 4. ;) American Gladiators is so superior, I could watch reruns all day. Fond memories. Your arguments are legit, but AG gets my nod for sheer overblown, bloviating pageantry. ;D

My bracket is blown, too. I had American Gladiators in to take the whole thing. :)

Okay you two, let’s talk American Gladiators, which I too enjoyed the hell out of when I was 11. But remember, this isn’t a competition about what was the most fun. We’re looking for what tells you the most about American violence. What are the lessons American Gladiators teaches us?

Full disclosure: I’ve never seen American Gladiators or American Ultra, so my pick had nothing to do with my analysis of either (poor Overthinking, I know). I know several members of the OTI Staff are big fans of WWE, so I thought they’d champion American Gladiators on the same merits.

Alternatively, while I don’t have many thoughts on American Gladiators as it pertains to violence, I did think it seemed quintessentially American. While many of the other entrants had somewhat universal themes about the morality of violence, the cycle of violence, and other ideas that could translate to other cultures, something about American Gladiator just feels like it could only exist in America.

While my love of AG is frankly the most underthought thing ever, when really digging in, I think it could teach a lot – America’s call to violence is often cartoony and overblown like AG. In your comparison, I feel you give the nod to AU solely on the basis of gun inclusion. But on an equal playing field, AG is moderately more telling a piece of American violence. Consider your own words – “This is a show that was aired on weekend afternoons for kids.” Kids watched this! For fun! We were inculcated to violence (so fun and cartoony! hah! those poofy q-tip staffs!) that we now think nothing of watching MMA fights, with actual blood spattering the mats. Unthinkably violent TV viewing 20, 40 years ago.

And compared to cacophonous freestyle of live TV, AU was a scripted and well-shot piece of cinema with carefully-cast “normal” people that nevertheless got professional training and stunt doubles. While I don’t have the wherewithal at the moment to go into detail, AG pulled from -actual- Average Joes with no stunt doubles. Granted, they were more like Above-Average Joes in order to stand an even remote chance against their opponents, but still! The ultra athletes (Olympians and such) were special cases, from what I can tell on the wiki; I’d have to watch through some episodes on youtube tonight to really get a sense of who the regular contestants were.

Honestly, I have no beef with your final judgment – my TL;DR is simply “American Gladiators taught America’s children (-children!-) that competition through violence is funny and awesome, and what’s more American than that?”

One of my misgivings about American Gladiators is that I’m not sure how violent it really was. They wrestle, they try and push past each other, they file tennis balls at each other. But where is the line between violence and sport? This certainly wasn’t the WWF, where they were really supposed to be pummeling each other. Of course, there’s a perfectly good argument to be made that while American Gladiators may not have been violent persay, it was a gateway drug to greater violence.

However, there are still a number of themes in American Ultra that I didn’t discuss here but deserve a discussion in the next round:

* Paranoia and violence. The government is lying to you, the media is lying to you, even your loved ones are lying to you, and it’s time to fight back.

* The redemptive power of violence. Mike is a lovable loser. But once he discovers that he can decapitate people with household objects, he gets to live the jetsetting life of an international spy. All his dreams come true, thanks to his talent for murder.

* Violence and gender roles. Mike and his girlfriend are a modern couple where she’s smarter, makes more money, and she’s more capable than him in every way… except for in her ability to kill people. Once she’s kidnapped, he gets to finally be a man. The violence “corrects” the gender dynamics.

I would hesitate to say “redemptive” power of violence, so much as “transformative.” ;D Redemptive implies something has improved, and I would argue that discovering within one’s self a capacity for freewheeling murderation is… uh… not super awesome… But I see your point in that “DUDE, VIOLENCE, YEAH! WOO! MANLY MEN GETTIN’ [sexist term] AND KICKIN’ [derogatory term]’S BUTTS!” is a quintessential American trait

I’m clearly unAmerican!

This is a good point. I do think that within the context of the movie, Mike’s discovery that he’s a badass assassin IS presented as redemptive. When he starts telling his story he says “We were the perfect fucked-up couple. She was perfect, and I was the fuck-up.” The violence reveals the truth, which is that Mike is the real star in the relationship, and she’s just his “handler,” and his life is immeasurably improved (in HIS opinion).

And let’s not ignore that the two people who conspire to erase Mike’s memories of his violent skills in the first place are women: his lover and his surrogate CIA mom. Really, there’s a lot of troubling ideas about masculinity being presented here.

I think you’ve laid out a good argument for AU winning over AG, but for personal reason, I would like to make some pro-AG arguments.

You see, American Gladiators was part of my literal introduction to America. When my family and I move here from South America I was 8, and there was about a 1-2 week period where we stayed in one of those hotels with kitchens and living rooms until we got a more permanent situation. During the day, my mom would go off and look for a place and do all the errands that moving to another hemisphere requires. My brother, 10 at the time, and I would sit at home watching TV. We must have watched plenty of dumb shows, but American Gladiators was the most memorable. In large part, because it was the thing that seemed most completely foreign to me. It was the thing that most said: “Hey kid, you’re in a whole different world now, and this is what this place is like.” It was also the one that was easiest to parse, without speaking any English.

One argument for it’s ‘Mericanness over AU, is an extension of your underdog theory. But I think it’s more American to have to work hard to prove you’re an underdog, than to be an actual underdog. America so loves to be the underdog that it creates all sorts of fictions to see itself that way. America has the biggest Army in the world, it has the currency that is used to measure all other currencies, it can do whatever the hell it wants, whenever it wants. But it always claims to be the underdog. he only way for this claim to make any sense is to be fiction. A an example, take the best Rocky movie: Rocky IV. Think of the massive amounts of work the narrative of that movie has to make Rocky an underdog. It has to explains why the guy who won three other championships might not be able to this time. It creates a villain whose punches create enough PSI to make a human head explode. And then it pretends that the USSR in 1984 is more technologically advanced than the US. But would the movie be any good without that fiction? No, because we want to believe that the little American underdog was able to punch out Communism, not that the USSR was buckling under the weight of 70 years of inefficient authoritarianism.

So I ask you, what’s more ‘Merican, having to fight off the gov’t with Cup-Soup, or investing millions of dollars into creating the fiction that an Olypmic athlete is an ‘underdog’?

Another Merican aspect of AG is it’s love for overly-complicated sports and games.

American football is a much more violent game than futbol. But it’s also way, way more complicated. Even Basketball, which would seem to be closer to soccer, has all kinds of rules and differentiation of points system that means it’s not obvious. In soccer, if the ball goes in the net, you get 1 point. End of story.

American Gladiators creates a whole series of elaborate games and contests, with a myriad rules and points, that frankly, are kind of pointless. But if it was just two guys punching each other or throwing each other out of a ring, it wouldn’t have seemed so foreign to me when I first saw it.

Finally, I think in terms of the theme of violence, AG has something ‘Merican that AU doesn’t. It very nicely encapsulates the ambivalence America feels towards violence. America is an exceptionally violent place. But at the same time it flaunts its own violence, it ashamed and afraid of it. the 2nd Amendment is sacrosanct, but those who do violence are seen as irredeemable and must be kept away from society. Children must be protected at all cost from being exposed to any hint of violence. And yet, they are fed a steady stream of it constantly in the media. For example, Disney, which is as American an anything can be, has a whole set of S&P rules for its shows to not let children see ‘real’ violence. And yet, most of its shows aimed at boys are ‘action’ shows where in a mitigated, obscured and declawed violence is crucial to the story.

American Gladiators encompasses this ambivalence. It’s named after a group of people who used to have to kill and maim each other for the sport of others. It was aimed at children. May of it’s contests were simulations of combat or violence. Yet they had been stripped of any real danger and were presented as harmless fun.

Again, I ask you, what’s more American than teaching children to simultaneously love and abhor violence?

Sorry about all the typos. I gotta proofread more.

Wow. Okay, you have made me officially repent of picking American Ultra. Bringing Rocky IV instantly makes your argument like 50% more compelling.

I do, however, really want to talk about the disturbing gender politics in American Ultra. It buys into this dangerous American fantasy that the way to prove yourself to a woman is by fighting and killing. Even if the woman is smarter and more capable than the man, she’s just a damsel in distress once the guns come out. So that’s why I wanted to keep Ultra around, but now I’m sorry I didn’t give more consideration to the Gladiators.

And I think that’s an argument for the AU side – whatever else AG was, I would definitely consider it gender-equal, and the Merican tendency to de-power (or else damsel-ize) strong women once The Schlub™ gets infused with power is not uncommon.

“But I think it’s more American to have to work hard to prove you’re an underdog, than to be an actual underdog. America so loves to be the underdog that it creates all sorts of fictions to see itself that way. ”

This nails it. We so desperately -want- to believe that Steve Jobs and Bill Gates (and their ilk) just happened to change the world from their garages, it’s this “gee shucks” bootstrapping mentality that has very little basis in fact. We don’t want to think about the systemic levels of privilege and interconnected support systems that assist people’s achievements (which is painfully obvious in every argument I have with a libertarian), we want to believe in the mythical self-made man that just doesn’t exist.

I’m looking forward to next week, when Sheely is going to address Capitalism and all those rags-to-riches narratives that have always been so powerful in our society.

I’m rooting for American Psycho, but that’s also because I have no idea what American Pickers even is. ;D (The irony of AP1, of course, is that the main character is played by a Brit. What’s more American than that, I ask you! (Besides everything.))

I would have chosen American Horror Story.

I’m looking forward to next week when hopefully I’ll know what more of these pieces of pop culture are before you tell me.

Okay, I’m curious. What do you think is American about American Horror Story? Ghost stories and violence aren’t uniquely American, although the series does its best to bring in as many American tropes as it can.