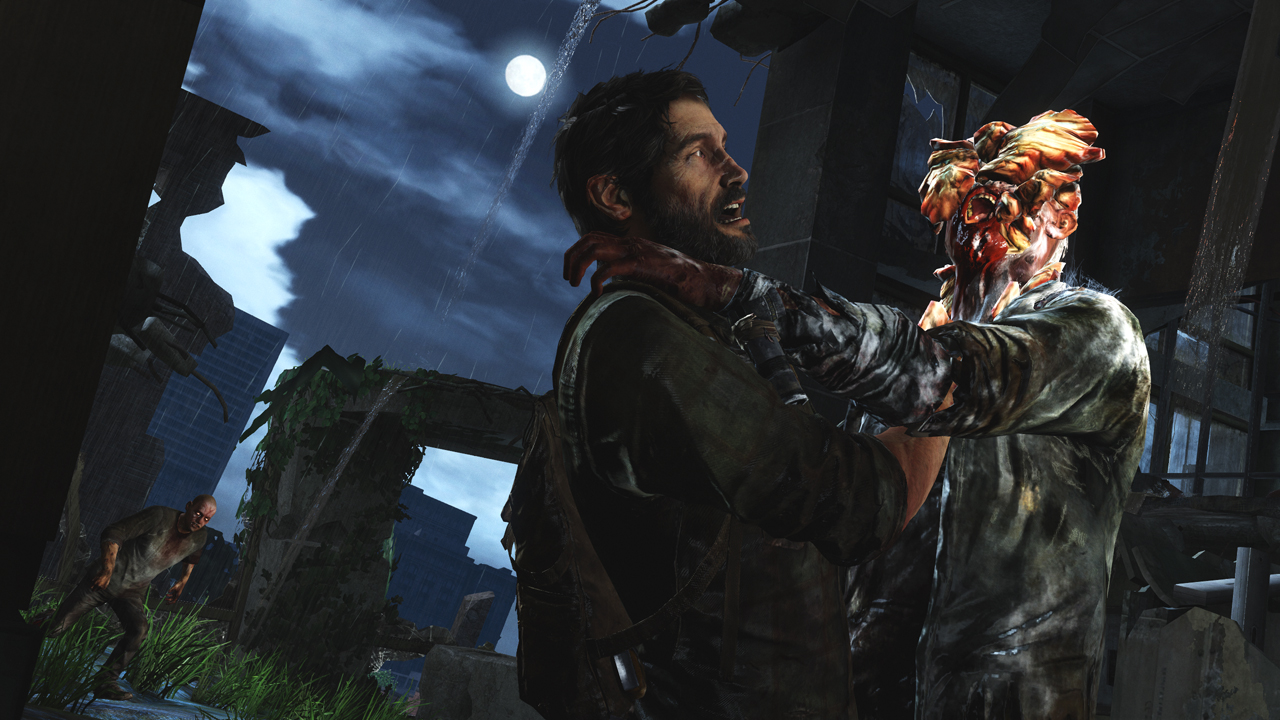

The Last of Us is one of the most critically acclaimed games of the 2010s. It features the smooth, cinematic gameplay for which Naughty Dog games has become so well known. Where so many AAA titles bludgeon their audience to death with dialogue, The Last of Us relies on the sparse, enthymemetic exchanges that we associate with the better TV dramas. And the story itself is intensely personal: while the stakes may notionally be the cure for a zombie apocalypse, it’s really about one broken man and an innocent girl and the bond they form while exploring the ruins of America.

Or, at least, that’s what I’m told. I haven’t made it past Bill’s safehouse yet.

Look unpleasant? It’s no more pleasant on an HDTV with adrenaline coursing through your bloodstream.

I’m at a weird cusp in video gaming, as I am in most fandoms: not ambivalent enough to be a filthy casual, not hardcore enough to be devoted to the grind. Pride keeps me from selecting the lowest difficulty setting in any game. But normal human endurance keeps me from sitting patiently while I die at the same zombie-ridden checkpoint again, and again, and again, and again, and again.

I had similar difficulty when playing Planescape: Torment for the first time about 9 months ago. One of BioWare’s first critical darlings, Planescape featured the quirky but endearing characters and the complex settings for which the Knights of the Old Republic series would later become famous. It’s one of those games people have raved about for years. And since Planescape is now available for cheap and easy download from a variety of sources, I figured it was time to see what the fuss was about.

And Planescape certainly lives up to the hype – to the limited extent that I’ve seen so far.

The problem in this case is that I’ve grown too accustomed to the style of contemporary gameplay of which Planescape, a mere 16 years old, is the primordial ancestor. Hit points that take hours to regenerate? No fast travel? Random encounters? No quest markers? None of these are huge burdens, but they’re little sources of friction that keep me from diving into the game headfirst. I have half a dozen other games in my pile that I can tackle much more easily.

It’s not as if I don’t like to be challenged in gameplay. But the challenge has to hit a certain threshold – tough enough that I can see the end within the reach of my skills. The reward has to be worthwhile as well. If I’m playing just for recreation, it has to be the most satisfying recreation available to me at the time. If I want to mow down hordes of enemies, I can slog through The Last of Us, or I can load in Just Cause 3, hijack a helicopter, and take on a mountain garrison.

And if I’m playing to uncover a fascinating story, the burden on the game is even heavier, because I can find fascinating stories all over the place.

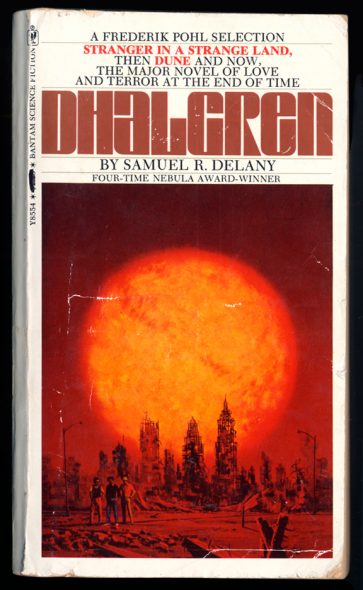

When I bought my dense paperback copy of Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren six years ago, the salesperson at Barnes & Noble said, “Good luck.” It took me three years to finish it – not three years of steady reading, but multiple attempts that usually fell off after the first hundred pages. But I finished it. I could probably stand to read it again, just to make sense of what I consumed, but it’s a hell of a thing.

Delany wrote at the height of science fiction’s New Wave, not its most accessible period (though for my money its most mature). And the subject matter he covered – race, sexuality, consciousness, hermeneutics – was not the most accessible to a straight white guy like yours truly. He’s got a rep for being challenging reading, and I started with what many consider his most challenging book.

(If you want to come at him in a more approachable way, I’d recommend starting with Babel-17, then perhaps Tales of Neveryon, then Trouble on Triton if you’re feeling up to it. I tried Stars in My Pockets Like Grains of Sand earlier this year but abandoned it early on – nonlinear, non-hetero, non-empirical narratives I can take, but nonhuman apparently baffles me. Soon, though)

But I managed. I managed because, as hard a read as Dhalgren might be, it’s written in English and I read English. Given enough time and patience, it can’t help but yield. There may be – almost certainly are – deeper levels of comprehension which an initial reading might miss. But I can get through the story. It’s not as if the skill eludes me.

The same can’t be said of the story of The Last of Us. Unless the game’s more sophisticated than I give it credit for, The Last of Us doesn’t make chapters or checkpoints easier just because I keep dying at them. I either need to master these challenges – figuring out the rhythm of dodge / strike / retreat that’ll keep me alive past a hoard of zombies – or I don’t bypass them. And if I don’t bypass them, I don’t get to experience this critically acclaimed story. The “story” of The Last of Us, for my purposes, is about a man and a girl who die in suburban Massachusetts.

When we talk about “challenging stories” in literature, we mean books like Dhalgren, or Ulysses, or Infinite Jest. They don’t all have to be doorstopping literary darlings, either. Novels with unlikeable protagonists or unreliable narrators – Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train, Herman Koch’s The Dinner – can challenge us as well. We don’t slip into these works with the ease of more conventional stories. Whether or not we find them rewarding is a matter of taste, but we call them challenging for a reason.

The word “challenging” in video games always means something else, though. Video games require a certain level of skill and patience to overcome: twitch reflexes, a feel for rhythm, mastery of the abilities a game grants you. But the story itself isn’t “challenging” in the same way.

It’s certainly possible to make a game with a challenging story and challenging gameplay. But the more challenging you make the gameplay, the harder it is for an audience to reach the story. I may launch into a painful sense-memory flashback once I bypass this giant dragon, but if I can’t evade its fiery breath and raking claws, it makes no difference to me.

It’s also possible to make a game with a challenging story and accessible gameplay. We see this most often in non-AAA titles: Papers Please, That Dragon Cancer, Depression Quest, Plague Inc. In these, the familiar Heroic Journey is subverted. The obstacles you overcome, the “triumphs” you simulate, often lead to a destructive or bitter ending. But the games themselves aren’t particularly hard, not when compared to the moneymaking AAAs released in the same year.

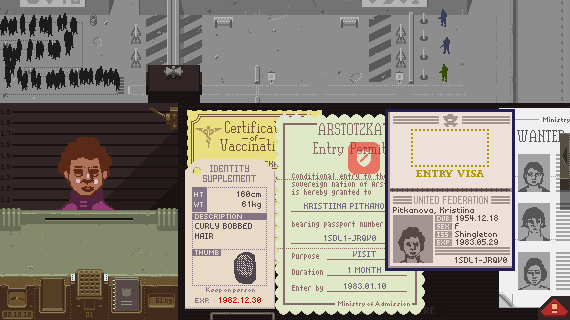

Let’s talk about Lucas Pope’s Papers Please for a bit. From the New Yorker‘s “Best Video Games of 2013” round-up:

It’s November 23, 1982. Your first task in your new job, as an immigration inspector at the Grestin Border Checkpoint, in the fictional European country Arstotzka, is straightforward: deny entry to all foreigners. The huddling, shuffling line weaves off-screen, and you must process as many would-be immigrants as possible, checking their documentation one by one, confirming or denying entry. The more people you process in a day, the more money you take home to your family.

A slew of additional rules arrives each day. As the red tape piles up, the number of people you are able to process by day’s end decreases. The fewer you process, the less money you make—the effect of which is revealed in a harrowing post-work financial breakdown, where, once you’ve paid your rent, you are forced to choose between spending your remaining earnings on heat, food, or, in the event that a family member falls sick, medicine.

The obvious question arises, “if Lucas Pope wanted to tell a story about the way bureaucracy grinds our humanity to dust, why didn’t he just write a book?” This is a pretty flip question with a pretty easy response: because he’s a game designer, not a novelist. Game design is the language he’s mastered, so Papers Please was the result. If he’d gone to Berklee Conservatory, maybe he’d have written a rock opera.

But video games are unique among art forms in that challenges are inherent in the medium. A modern balletic interpretation of a border control officer’s experiences in a fictional Eastern European country would certainly be inaccessible to a popular audience. I can feel my ass getting heavy just thinking about it. But it wouldn’t be deliberately inaccessible. Our theoretical ballet choreographer would have a reason for the interminable pas de deux, the ungainly costumes, and so forth. They’re not just doing this to be difficult.

A video game, on the other hand, must be at least a little inaccessible. It has to throw up deliberate obstacles. The fun of a video game comes from tackling obstacles and bypassing them. So there has to be a point at which the designer says, “Yes, let’s slow them down here“. She has to deliberately frustrate in order to eventually reward.

There may be a parallel I’m not generous enough to grant. Maybe our theoretical interpretative ballet is a story only meant for sophisticated dance connoisseurs, and our theoretical In Search of Lost Time cover shooter is a story only meant for experienced gamers. But different media require different consumers, and different levels of “sophistication” or “experience.” Expertise at video games does not make you an expert at film criticism, no matter how much today’s AAA titles feel like summer blockbusters.

What does this mean for our critically acclaimed indie games? For me, it means that a good story in a video game should not be judged by the same benchmarks as a good story in a novel or a movie. And that’s fine! I would even say that’s ideal! The purpose of a video game isn’t to deliver an untrammeled narrative, any more than the purpose of a Monet is to complement the frame it sits in.

The narrative of a video game has to invest the player with enough agency that they feel it’s worth continuing. If the game consisted of nothing but “press A for the next block of text,” it would be a Kindle. Even if the game scrolls left to right, allowing no retreat and only a few optimal means of bypassing each challenge, that’s enough agency to satisfy a generation of players – as Super Mario Bros. can attest.

While the narrative makes the game more memorable, engaging play must come first. This may mean that there are certain stories that will remain forever inaccessible to certain players – that I might never experience the later acts of The Last of Us, or the grand climax of Planescape: Torment. This is okay! There are other castles for me, other weapons to equip, other bosses to conquer.

These kind of questions are what’s fascinating about video games at the moment and the potential of them.

Games were often perceived as something to beat in the past, hence a lot of the aspects like ‘lives’ which were there to consume more money in the arcade.

As a narrative was tied more into games, there’s been more of what you mention of a story with challenges to move on.

Games have mechanics which themselves can be mechanised. The fail states in Papers, Please, are part of learning and growing, with several different endings to explore. The same goes for Rogue Legacy, where death of your character gives your child some inherited bonuses as you go on. The recently released Reigns, too, needs a fail state to progress the story as your king dies and the next one has the next set of challenges to complete.