If you’ve been reading Overthinking It for a while, you know that we have a serious obsession with the Terminator franchise. We’ve subjected Terminator to a level of scrutiny it definitely deserves…and then some.

We’re using the upcoming 25th Anniversary of Terminator 2 as an occasion to help introduce newcomers (either to Overthinking It or Terminator) to the many avenues of analysis that Terminator offers. This article gives a survey of the movie’s main themes and links to some of our previous work on these topics.

Enjoy, and let us know what you think makes Terminator so overthinkable in the comments!

What is Terminator?

This is actually a tough question to answer.

Factually speaking, Terminator is a science fiction movie franchise that spans five feature films and one TV series, along with various incarnations in other media forms (comic books, video games, a theme park attraction, etc.). But it’s also fair to argue that Terminator consists of just the first two movies: The Terminator (1984) and its sequel, Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). Most people who toss around this assertion cite two reasons for ignoring the rest of the canon: A) auteur James Cameron wasn’t involved in them and B) their quality ranged in quality from “just OK” to “outright travesty.”

The more interesting reason to define Terminator by just the first two movies, though, is that they are a pair of science fiction masterpieces engaged in a fascinating dialogue with each other, in ways that we rarely see with big budget action movies. More on that dialogue in a moment, but if you’re new to Terminator Studies, just know that the first two movies are required reading; the rest is optional.

What Makes Terminator So Overthinkable?

It’s a cautionary tale about technology…except when it’s not.

A key element of the Terminator “back story” (or “fore story,” since it technically takes place in the future) is Skynet, the genocidal artificial intelligence that nearly wipes out humanity in a nuclear holocaust (“Judgment Day”) and creates the titular killer cyborgs to pursue the survivors across space and time. The movies clearly state that ceding decision making power to technology was a Bad Thing, and in doing so has become inextricably linked to our real-world discourse around the ethics of artificial intelligence.

But it’s not as simple as saying that these movies are fundamentally anti-technology. If Terminator is anti-anything, it’s the alienation of humans from each other through intermediaries, technology being just one of them. In fact, technology is just as often the solution to problems as it is the cause. In The Terminator, Sarah Connor’s roommate can’t hear the Terminator murdering her boyfriend because she’s blasting music on her Walkman, but by the end of the movie, Sarah uses factory machinery to defeat her cyborg pursuer. In Terminator 2, our heroes blow up the world’s most advanced computer facility to save humanity, but they also use their own cyborg to defeat their pursuer and reconnect with their own lost sense of family and belonging. And in both movies, institutional law enforcement poses just as much of a threat to John and Sarah Connor as Skynet does.

There’s also the role of technology going on at the meta level; Terminator 2 was the most advanced application of computer graphics at the time. David Foster Wallace has argued that this fact undermines the movies’ anti-technology theme, to which I would reply: A) see above about how it’s not really anti-technology; B) Terminator 2 is awesome just get over yourself; and C) oh wait, sorry you’re dead, David Foster Wallace.

The Terminator and Terminator 2 present opposing but equally compelling arguments on Fate versus Free Will.

Are we destined to proceed down a path pre-determined by powers beyond our control, or are we able to choose our own destiny? Terminator offers up two contradictory, or rather, complementary, answers to this question. In The Terminator, Sarah accepts role as the mother of humanity’s salvation and begins preparing him for the future war. Fate. In Terminator 2, she makes a very deliberate attempt to change the future by blowing up the computer facility that would eventually become Skynet. Free Will. And yet…the final shot of the movie simply shows an open road, leading to an undetermined future. Within the confines of these two movies, we don’t know which side wins out, and we’re left to contemplate whether or not Fate of Free Will ends the day.

(Subsequent movies and TV show try their best to undermine the neat dichotomy presented by the first two movies, but the less said about them, the better.)

No Fate But What We Make: The Greatest Terminator Lie Ever Told

It’s a standout example of how modern storytellers invoke Biblical ideas to heighten stakes and expound on key themes.

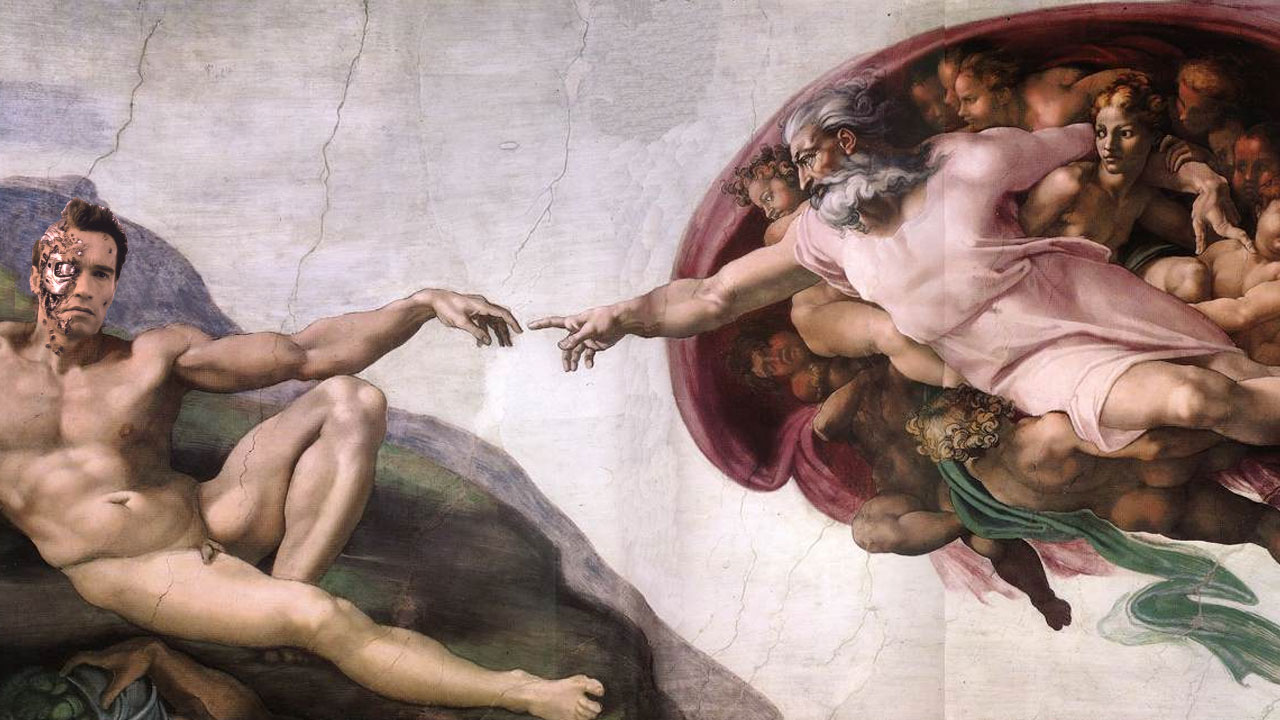

Terminator (in particular, Terminator 2) is a great example of “poetic authority,” a theory that states that creative works strive to supplant, support, sustain or otherwise build upon the role of Scripture as a literary operation. They attempt to imitate the relationship between the poetic language of The Bible and the Authority it implies in order to imbue their own works with that feeling of importance.

Not all action movies do this, but Terminator 2 does it in nearly every scene. John Connor makes moral proclamations that echo the Ten Commandments (“You can’t just go around killing people!”). Angels and demons make war (T-800 vs. T-1000). Men are punished for their sins (Judgment Day), but also redeemed after dramatic revelation and conversion (Miles Dyson).

And of course, our savior dies for our sins.

“And at the ninth hour Jesus cried out in a loud voice, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani,”–which means, ‘I need a vacation.’” Mark 15:34

It’s cornball and over-the-top, but it’s also a beautiful story that reveals essential truths about the human condition. Like the Bible.

Sarah Connor is one of the most compelling depictions of womanhood and motherhood in all of film.

Sarah Connor spends much of the first film in terror, running away from a mechanical monster. But by the end, she’s transformed into an active agent in her fight against the Terminator. As if that weren’t enough, she also becomes a vessel for the future of mankind; a mother to us all.

By Terminator 2, she undergoes a radically different character arc, transforming from a cold-blooded, paranoid killing machine into the nurturing mother for her formerly estranged son, who she learns to see as a human being, not an abstracted future savior of the human race.

Sarah Connor was ahead of her time in 1984, and again in 1991, and sadly remains the exception rather than the rule in 2016 when it comes to female characters in action movies.

The Terminator, as embodied by Arnold Schwarzenegger, is an inexplicable bundle of contradictions that achieves greatness because of–not in spite of–his flaws.

Arnold’s career-defining role as the Terminator is so firmly planted in our culture that it’s easy to take it for granted. But nothing about it makes sense, at all. If he’s supposed to blend in with humans while on time-traveling assassination missions, why on earth does he speak with a thick Austrian accent? And why is he so insanely buff?

It’s a testament to how well these movies are put together that audiences didn’t reject this outright and check out from the movie the minute he shows up and opens his mouth. But it’s also a testament to the quality of Arnold’s performance. His muscular form dominates the screen, and his wooden, monotone delivery satisfies some part of our brain that expects a robot to sound like, well, a robot.

The whole package actually works in the service of dramatic irony. Arnold looks and sounds ridiculous to us, the audience. The characters can’t see it, but we know it all too well.

The Terminator, as embodied by a metal endoskeleton, is a ghastly reflection of the human condition.

Why is the image of the metal skull with those red eyes so arresting? Perhaps it’s because images of skulls activate the same part of the human brain that’s used to recognize faces. Or perhaps it’s a reminder of the Terminator within us all: strip away any human’s exterior, the thin veneer of politeness and morality, and you’re left with a skeleton, a monster. An uncontrollable, unstoppable monster with an unquenchable lust for human flesh.

What Doesn’t Make Terminator Overthinkable?

Time travel.

Here’s the dirty secret to Overthinking Terminator: the time travel doesn’t matter. All of those complex charts that try to map out the different timelines and causality sequences? For the most part, all they do is highlight the fact that the time travel logic makes absolutely no sense. But it doesn’t matter! Time travel is important only in that it provides a setup for the Fate vs. Free Will conflict and the visual dissonance of futuristic robots battling in (then) present-day Los Angeles. The future war that’s depicted in prologues, flashbacks, and dreams is deliberately set aside from the main events…because they don’t really result from, or cause, the events we see in the main event.

Remember, time travel is considered to be a paradox for a reason. It’s not supposed to make sense. That’s why most of the Terminator stories past Terminator 2 fail; they interrogate and explore aspects of time travel and the future that the first two movies were smart enough to leave alone. Trying to make sense of the time travel isn’t satisfying from a story perspective, and it isn’t intellectually rewarding from the Overthinking perspective.

Enroll In Our Terminator Studies Program

I’ve highlighted only a handful of the many articles we’ve written on Terminator; browse the complete listing here. There are tens of thousands of words exploring everything from T-1000 mitigation strategies to my conspiracy theory that Grease 2 and Terminator 2 are related:

But for the Ultimate Treatment, be sure to download The Overview for Terminator 2. Watch the Greatest Action Movie of All time while the Overthinkers provide commentary in sync with the movie. Just $2.99, or free for members at the Well, Actually and Full Harvey levels.

Add a Comment