A month ago, I volunteered to write an article with some hot takes on Kanye West’s new album SWISH right after its February 11 release. However, as the month marched on, I started to doubt whether or not Kanye would hold up his end of the bargain. Over the last few weeks, he has changed the album’s title twice (from SWISH to Waves and from Waves to The Life of Pablo). He has started twitter feuds with Wiz Khalifa, Amber Rose, Michael Jordan, and anyone with an ounce of decency in their body. And he’s been stretching himself thin between tweaking the album up until the last minute, micromanaging the launch of his new Adidas fashion line, and planning a fashion show/album listening party in Madison Square Garden to coincide with the February 11 release date.

The whole event reminded me a lot more of a manic all-nighter to finish a term paper or a performance art project than the release of one of the year’s most anticipated pop albums. And for the rest of February 11, The Life of Pablo inhabited exactly that kind of existential nether-world. The album was not immediately made available to stream or download anywhere, other than Tidal’s perpetually looping rebroadcast of the live event. For a brief moment, it simultaneously did and did not exist.

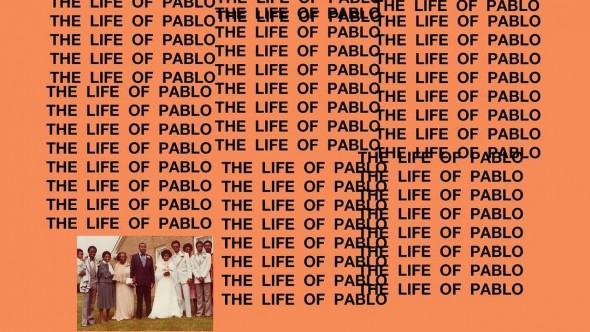

A Screen Capture of a Livestream of an Album at a Fashion Show

And here’s the thing…for an album that entered the world only as a streaming video of a listening party, it is phenomenal. It draws on nearly every step of Kanye’s evolution as a musician and producer, from the warm soul samples of The College Dropout, to the cinematic strings of Late Registration, to the electronic music influences of Graduation, to the Autotuned crooning of 808s and Heartbreaks, to the saturated maximalism of My Dark Twisted Fantasy, to the ugly emotion and dark electronic noise of Yeezus. But this isn’t just a greatest hits collection where Kanye does all of his old tricks at the same time, it is a skillful and creative synthesis of his own body of work in the service of making something new. Kanye’s vocals match the diverse texture of the beats, alternating between stretched out sing-rapping and raw verses that have the loose feel and raw energy of a spontaneous freestyle. And like the best Kanye West songs, the lyrics make you laugh, they make you anxious (and a little worried for Kanye), and occasionally they make you cringe.

In the coming days and weeks, critics will inevitably measure the success of The Life of Pablo as an album by the extent to which it is able to transcend the last-minute rush to finalize album details, the social media antics, and the concurrent fashion show. That tendency is a mistake. Rather than being a distraction from the music on Pablo, everything else that led up the release of the music is an intrinsic part of what The Life of Pablo ultimately is- a piece of multi-media, multi-platform performance art that deconstructs and ultimately dismantles the idea of the “album” itself.

The Surprise-Spectacle Dialectic: Anti-Beyoncé is the New Beyoncé

The protracted run-up to the release of The Life of Pablo is in stark contrast to two other album-release models that currently dominate the record industry. One is the standard model that largely predated the internet… artists record an album, and the record label schedules the release of that album, and a corresponding schedule of promotional singles, music videos, and tours to promote that album. This model persisted for a bit after the initial rise of file sharing, it was pushed to the brink of collapse with the rise of album leaks which often deflated the carefully choreographed cycle of album release and promotion that had been a cornerstone of the industry for years.

The second model that T.L.O.P. deviates from is the “sneak attack” model pioneered by Radiohead’s 2007 release In Rainbows (which was announced ten days before it was released as a pay-what-you want download) and was perfected by Beyoncé on her surprise self-titled 2013 album. For both In Rainbows and Beyoncé, the surprise release pre-empted the leaks that plague nearly every other contemporary album. This is in part because of the element of surprise itself (especially in the case of Beyoncé’s album), but also in part because in both cases, the artists controlled the release and excluded the many layers of the record label-promotional complex that created opportunities for leaks in the older model. After the success of Beyoncé’s surprise album drop, “pulling a Beyoncé” and releasing an album with little to no advance notice or promotion became commonplace for many major releases in 2014 and 2015.

By publicly announcing details of the album and setting a very visible (and hard to break) deadline for his new album with the Madison Square Garden listening party, while also documenting every hiccup, doubt, and last minute change, Kanye broke with both the old “release date-promotion machine” model and the “Beyoncé sneak attack” model. By publicly setting the release date well before he had finished the album, he ensured that he’d have to have something made by February 11 (or give a LOT of people their money back). At the same time, his constant vacillation about details of the album and his picking of fights that apparently had nothing to do with making the album started to raise questions about whether he’d actually meet his deadline. Even up to the moment that Kanye plugged his laptop in to the soundboard and pressed play, I wasn’t entirely sure that there was actually an album on there and I half expected him to just stare at the audience in silence for two hours (much like his models were required to do).

“There’s actually an album on this laptop, I promise.”

All of this adds up to make The Life of Pablo feel more like a piece of process-based performance art than a traditional album that is “released”. For all we know, Kanye may never release Pablo and instead will travel the country with his laptop and his army of neutral-clad models, playing this evolving collection of songs that he keeps tinkering with and re-recording between each stop.

What album?

This hypothetical Pablo Roadshow might actually be truer to the vision of the project than any canonical digital or physical release of the album that eventually materializes. Many of the musical and lyrical themes on the album reinforce everything that Kanye did and said leading up to during the Madison Square Garden event. As with Kanye’s last several albums, the songs on Pablo contend with and work through a set of apparent contradictions, between beauty and ugliness, between family and alienation, between spirituality and sexuality, and between reverence and irreverence. At the core of the album is an acapella freestyle in which he addresses the battle between the “old Kanye” everyone loves and the “new Kanye” everyone hates. This excerpt echoes Kanye’s public performance of “Kanye-ness” over the past month or so and is a lens that helps to interpret both his frequent assertions of wanting to bring “as much beauty to the world as possible” and the extreme ugliness of his Twitter assertion of “BILL COSBY INNOCENT”.

Pablo, Pablo, wherefore art thou Pablo?

If The Life of Pablo is best understood as an evolving piece of multimedia performance art, then it raises the question, what exactly is the point of this artistic project? Part of the key to answering that question is in answering a simpler question: Who is the Pablo referenced in the album title?

The easy answer that many commentators are suggesting is that it refers to Pablo Picasso, based on a moment in Kanye West’s 2015 Oxford lecture in which he stated that his artistic goal is to be “Picasso or greater”. Other theories argue that the Pablo in question is the drug kingpin Pablo Noreaga, the poet Pablo Neruda, or the soccer player Pablo Zabaleta.

Given that the music and lyrics of the album play with contradiction and ambiguity, my sense is that that there is no one true Pablo, but rather a rotating cast of Pablos that Kanye inhabits throughout the album. In that spirit, I want to suggest one other possible “Interpretive Pablo” that has been overlooked so far: Pablo, Honey.

The phrase Pablo, Honey has two meanings in the popular culture and both are helpful in making sense of The Life of Pablo. The phrase originated as a prank call bit on an early 1990s comedy album by the Jerky Boys in which one of the Jerky Boys repeatedly asked a man named Pablo annoying questions about the cleanliness of his butt (full disclosure, I loved this album and this bit in particular when I was twelve years old).

This inane bit (which was on an album of similarly inane bits that eventually went platinum) inspired the second instance of Pablo, Honey, Radiohead’s debut album (full disclosure, I also loved this album around the same time, but for very different reasons). This Pablo, Honey is much more serious in tone and artistic intent, most famously in “Creep” in which Thom Yorke gave voice to the inner life of a whole generation of weirdos.

These dual strands of juvenile trolling and morose introspection both run through the core of Kanye’s The Life of Pablo and his broader public performance surrounding the creation and release of the album. At some moments, Kanye reaches for the genre-defining artistic heights of Radiohead, as on the gospel-inflected opening track “Ultra Light Beams,” which sent shivers down my spine the first time I heard it. In other moments, he lands much closer to the in-poor-taste vulgarity and problematic sexual politics of the Jerky Boys, as when he fixates on bleached assholes, having sex with Taylor Swift, and whether or not all of the women at Equinox gym are freaks or not.

Viewing both of these instances of Pablo, Honey as interpretive lenses through which to understand The Life of Pablo helps to bring our attention back to how and why Kanye has created a post-album album. The same market forces that ensure that we’ll probably never again have another platinum-selling album by either Radiohead or the Jerky Boys also explain why Kanye drew on all of the Pablos (Honey, Picasso, Escobar, Neruda, et al) to embed his music in an evolving and confounding artistic project that will never truly be released, even after it hits the streaming services and record stores.