Jordan Stokes: I want to talk about X-Files.

So far, I’ve watched the pilot, which is kind of hilarious. It begins (as you would have to) with something like a “previously, on the X-Files” voiceover, laying out in the broadest possible terms some of the show’s central mythology.

And then the plot of the pilot episode itself can be boiled down to:

“But what if… NOT… all that stuff we just said?”

“What if the conspiracy that we spent ten seasons of TV and two movies explaining to you was total BS, and the real explanation is totally different conspiracy that was even way more awesomer?”

Richard Rosenbaum: One thing that I noticed while watching the first couple of episodes is how different the conspiracy rhetoric affects me. When X-Files was around the first time, although it obviously used stuff that some people actually believed, I thought it was cool but that’s all. Now, when they talk conspiracies, I’m actually concerned about whether the show is lending credibility to to this stuff because of all the current conspiracy theorist rhetoric floating around in the cultural sphere. I do wonder about whether or not X-Files will explicitly acknowledge the coincidence between 9/11 and the plot of one of the episodes of Lone Gunmen.

Matt Belinkie: On the one hand, you would think that paranoia and conspiracy theories have only become more ingrained in our national character since the show was on the air. That should give everything new relevance. But it also makes things less fun.

Stokes: There’s a line in the pilot that begins “Since 9/11,” and I forget how it ends because I was too busy being terrified that the X-Files was even going there.

“Zero point energy can’t melt steel beams!”

Stokes: Anyway, this plays into something that I’ve been wanting to write about for a while now, which I call the Gnostic Plot. In gnostic plotting (as in gnostic religion), the story revolves around the gradual revelation of a piece of information which challenges your basic understanding of the nature of reality. After the reveal, the narrative stakes from the beginning of the series turn out to be meaningless.

So, like: “You were worried about whether God wants you to eat pork? Well, let’s see how much you care about that when I tell you that the being you call “God” is the blind and gibbering demiurge Ialdabaoth, who has, like, a billion heads!”

Or alternately: “You were worried about, like, a polar bear in the jungle? Well let’s see how much you care about bears when I tell you [whatever Lost was actually about]. (Shana, I read all of your recaps, and I still can’t even grasp the fuzziest outline. And I know you’re a good writer, so I blame Lindeloff.)

Peter Fenzel: Like if Bilbo were to actually realize he had come across the One Ring before he reached Smaug and the rest of the story was about whether Bilbo would choose to rule the world and destroy himself.

Fenzel: Or Phoebe from Friends realized the original Phoebe was dead and she was a clone with implanted memories. But gradually. Like the “Whispers” episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

Rosenbaum: What was so confusing about Lost? It was a magic island.

Stokes: Richard: Oh, now I get it. Why didn’t I think of that before?

Magic Island?

Stokes: Other good examples would be the Zelda game for gameboy, Link’s Awakening, where ultimately none of the people or places in the game turn out to really exist. The Da Vinci code, where it turns out that Audrey Tatou is Jesus’s grandniece, or something.

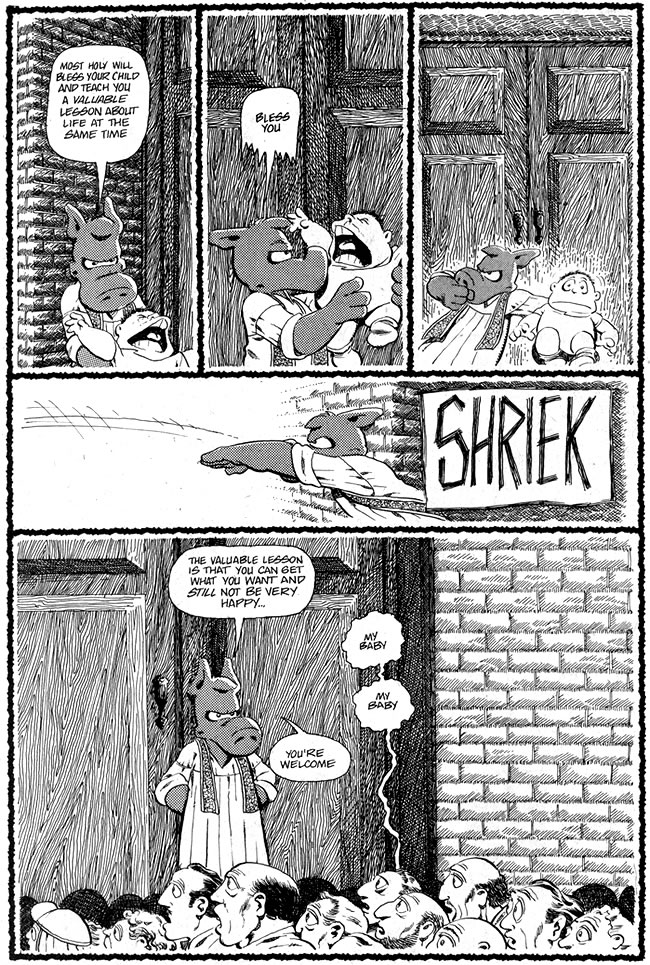

Or Cerebus the Aardvark, which was pointed squarely in this direction before running headlong off a cliff of misogynistic rage.

Ben Adams: Burn Notice had a recursive version of this, where every time he found out who was secretly pulling the strings, it was quickly revealed that there was yet another even MORE evil and MORE secret globe spanning conspiracy.

Stokes: And conspiracy theorists want the real world to work this same way. “You’re bothering to vote for one of the Democratic or Republican candidates? Don’t you know they’re all secretly lizard people?”

Yes, Burn Notice is a perfect example! It shows both the power and the weakness of this kind of plotting. The first two times they do it, maybe, you’re like: HOLY CRAP!

The fifth time, you’re like, “Oh, whatever. Can’t we check in on what Bruce Campbell is up to?”

Rosenbaum: Wait, when was Cerebus pointed in that direction? I mean, he learns the intricacies of statecraft and the origin of aardvarks and things, but at what point was it gnostic? Except, I guess, in the literal sense that the last couple voumes were a parody of gnostic Christianity mixed with Talmudism.

Stokes: Ok, so in volume 1, Cerebus just wants gold and ale. In High Society (the high point of the series, if you ask me), he learns that there’s more to life than gold and ale: he wants to be prime minister. In Church and State, he transcends his quest for temporal power and ascends to godhood, sort of, only to have the rug pulled out from under him at the last minute. Then the series then sort of does a meta-textual Gnostic plot: “Oh, you thought you cared about Cerebus’s sword n’ sorcery adventures? Well let’s see how much you care about that when it turns out that this is actually an artsy-fartsy meditation on the prose of Oscar Wilde?” Or something. (At this point, it’s still one of the best comic books running.) The specific moment I was thinking of, though, is the point in the Flight/Women arc where someone drops this truth bomb on Cerebus: “There are two other Aardvarks in Estarcion.”

All throughout the series, the fact that Cerebus is an aardvark has been just a goofy joke. (Because the series started out as a goofy joke plain and simple.) Suddenly, it’s laden with metaphysical significance. Aardvarks are imbued with magical potential to transfigure the world: all three of the Aardvarks lead or have led major world religions — never mind that Cerebus was just trying to use the papacy to scam his way into wealth and power. And it turns out that wealth and power are, like, no longer meaningful concepts. The struggle between the Aardvarks is now a struggle over the nature of reality itself. Or something like that.

(The following volume is Reads, a.k.a. the point at which Dave Sim goes colorfully insane. I never picked it up.)

Rosenbaum: Right, okay. The Tarim stuff was there from the beginning, and we knew that Cerebus was raised religious, but then we couldn’t have expected it to get so metaphysical from looking at the first volume or so.

FWIW, apparently Sim’s getting divorced coupled with some kind of LSD-induced psychotic break is what made Cerebus’s weird left turn happen, but the couple of times I’ve met him IRL at signings and things he was perfectly coherent and polite – and just as many women as men were there as fans and he didn’t start accusing them of trying to steal his Male Light or his Precious Bodily Fluids or whatever.

Stokes: Yeah, I shouldn’t call him insane. It’s mean and inaccurate. (But I did dip into a few of the later issues of Cerebus… boy howdy.) My point, though, is that even the transition from Cerebus to High Society is kind of a Gnostic moment, in narrative terms. (Because it turns out that ale and gold don’t matter: power matters.) It doesn’t have to involve anything supernatural: the distinctive feature of the Gnostic Plot is that the shift-of-frame, such that the issues that the story used to be about seem trivial to the point of irrelevance. The plot is a line: suddenly, we shift focus, and it’s a square. The square becomes a cube. The cube, a tesseract. And so on.

And I think this is more or less what the X-Files reboot is trying to accomplish. “You thought you knew the story? Everything you thought you knew is wrong!”

Rosenbaum: Which really always has been the show’s theme, right? It’s about secrets wrapped in secrets and the obligation to discover reality even if it’s impossible. Every conspiracy is a front for a larger one.

There’s still a lot of really good (if bizarre) stuff in Cerebus post-Reads, by the way. Dave Sim completely breaks the fourth wall in Minds, and Cerebus spends basically the entirety of Guys standing one spot. Basically read until the end of Form and Void and then you can stop, unless Biblical exegesis is really your jam.

Fenzel: I’m really not willing to assent that Cerebus doesn’t get crazy, in the sense of toxic, motivated by mental illness, mania, paranoia, and not healthy to read too much if you’re in a vulnerable place. And I don’t mean like GWAR crazy, I mean actual mental illness crazy, which is a rude word to use, I know. I read the whole thing, and it had its beauty and its glory (Jaka’s Story was really great, there’s that sort of exhausted place in the Hemingway and Fitzgerald books where he stops being quite so maddened and maddening for a while), but as a whole it kept me up at nights and made me want to soul-vomit (especially the really long Woody Allen sexual apologia). I eventually think I threw out most of my Cerebus phonebooks because it was too troubling to even have the latter ones in my house. There’s good and bad sides, but if it’s a package deal of choosing either “Cerebus is fine and LOST is coherent on its own terms” or “Cerebus becomes deeply crazy and LOST changes what it’s about in confusing ways” I’m going to lean toward the latter.

I do think it going from being a Conan the Barbarian parody to being a political parody to being a religious parody to being what it became is the kind of change Jordan’s talking about.

But yeah, at any rate, moving on from that. Gnostic plots. Did the X-Files previously have gnostic plots, or does it only have them now?

Stokes: I think that the “mythology” episodes of the X-Files were always moving in this direction.

If I remember right, at the very beginning of the show the question is more or less whether aliens really exist or not. You figure out that they do super quick, but there’s a point at which Mulder is just trying to get some concrete evidence that they’re real. But pretty rapidly you get the sense that there are wheels within wheels — and that the secret is going to be a game changer.

You can imagine some hilarious counterfactual plots: imagine Mr. X explaining to Mulder that the aliens are providing material assistance to the secret one-world-government in exchange for… aluminum!

Mulder: “What, like all of earth’s aluminum?”

Mr. X: “No — I mean, a bunch, but nothing we can’t afford to sell them. It’s just really scarce on their planet. Supply and demand.”

Mulder: “This feels underwhelming.”

Mr. X: “This is why we’re supposed to ‘recycle’ our cans!”

“… I devoted my entire life to this?”

Stokes: No, the real plot has to be something more morally monstrous: something that shakes your faith in human nature. But the difficulty with these kinds of plots is that, while it’s easy to hint at a game-changing secret, it is wicked hard to deliver one.

The concrete answer is almost always a disappointment.

Fenzel: And a lot of shows just plain chicken out and sidestep their own essential questions. It is perhaps the difference between “The Truth is Out There” and “The Truth Is Not In Here.”

Are you excited because you are chasing something transformative, or are you excited because of the dawning horror that what you have is inadequate, with searching as a time-killer? Avoidance?

Rosenbaum: Yeah, I really have got a feeling like Mulder has just been wasting his life. Let’s say he proves that aliens exist and government conspiracy and bloobady bleebady. So what? Does the world really change so much? What’s it got to do with the price of tulips in Holland? People still have to go to work, search for love, raise their kids. People still want to have a beer and watch the game or the latest Nicholas Sparks tear-jerker. How is anyone’s life improved by this knowledge?

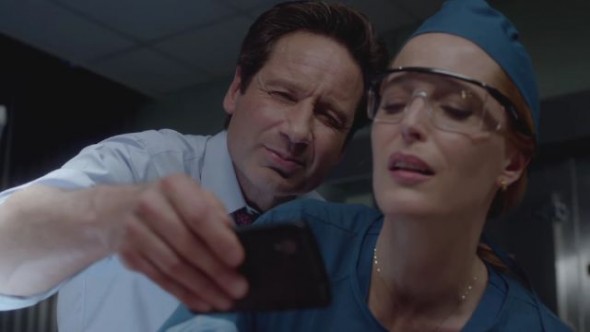

Actually this week’s episode addresses this question – and is also amazing and hilarious. Anyone see it yet?

Fenzel: The episode was so, so funny. And also such an abrupt tonal shift from the first two episodes. I wasn’t a big X-Files guy when the show was out; is it normal for the show to have episodes like this that disregard its level of suspension of disbelief? Do they just kind of reset afterward, or from here does Mulder go on with the knowledge that there are 10,000 year old lizard people sleeping in caves and never revisits it?

Rosenbaum: There have been a number of episodes like this, and while I don’t think that the implications of any of them have ever been returned to, there’s also no indication that they’re non-canon. X-Files officially includes an alien baseball team, mind-swapping, and genies – stuff that really pushes at the limits of the audience’s suspension of disbelief for comedy’s sake but the episodes are also self-contained so nothing that happens in them are important for the overall mythology.

Fenzel: So, spoilers for those unfamiliar, in the latest X-Files episode, Mulder has a bit of ennui and a crisis of confidence about all the fairly stupid and cliche creature feature adventures he’s had over the years, and how most of his monster hunting ends up being pointless. But, he and Scully are sent to the site of a seeming were-monster murder and investigate it. It is rife with cliché and callbacks to previous episodes, and Mulder plays both the Mulder and the Scully, talking to himself about his skepticism and speculation while Scully just watches him in smug enjoyment.

Eventually, they find not a were-monster, but a were-man, a giant bipedal lizard that was bitten by a human and periodically transforms into a human because of it, which comes with a bunch of horrific consequences: he gains self-awareness and realizes he’s mortal, he realizes he’s naked and needs clothes (he spends a lot of time in lizard and human form running around in tightie whitie underpants, Walter White style), he’s compelled to drink coffee, watch porn, and find a sales job at a cell phone store, he can’t help bullshitting his way through conversations and exaggerating his sex life, all this mostly everyday stuff which is entirely strange to him.

The murderer turns out to be the animal control guy, who has a whole serial killer backstory about his psychological problems, but it is so cliche at this point that nobody cares and they just interrupt him as he’s getting started with this big speech and haul him away. It’s a particular delight when Scully goes to confront him herself, which Mulder keeps warning her not to do, because she always gets kidnapped or whatever, and instead we cut away and cut back and she’s tackled and handcuffed him and is fine.

The were-man is played by the manager from Flight of the Conchords, and the animal control guy is played by a deadpan stand-up comic and X-Files superfan.

It’s all incredibly silly and a sheer delight.

It’s also delightful when the lizard man rebuffs Mulder’s attempts to deduce the internal logic of his transformation by rattling off to him that he doesn’t know how anything that is happening to him works, and life doesn’t have any external logic, so why should his have internal logic?

Matt Wrather: “Deadpan stand-up comic” is Kumail Nanjiani, who plays Dinesh on Silicon Valley.

Fenzel: I should have looked up both their names, but I’m multitasking with Nicholas Sparks movies.

Rosenbaum: He’s fantastic, by the way, Kumail Nanjiani. One of the best comedic actors working today. I was so happy to see him in this episode.

Stokes: As is the Were-Monster, Rhys Darby. And Richard Newman, the psychiatrist. Hell, the paint-huffing stoners from the opening were on point.

An interesting little detail: last week’s episode, with the superpowered mutant alien children, was supposed to be episode 5, but they rearranged them. Now that one, to me, felt like a VERY normal X-Files episode: not that it was bad, or anything, but it was a fastball down the middle of the plate, you know? Whereas the season opener and “Mulder & Scully Meet the Were-Monster” are, each in their own way, change-ups.

My guess would be that the original episode 2 is also off-model: probably it follows up on the new-big-conspiracy angle from the first episode — it’s weird that they’ve dropped that entirely in these two episodes, no? — but they decided to throw some red meat to the base, first.

Stokes: So Richard, to your point about Mulder wasting his life: this episode definitely raises the question, but do you think it provides an answer? My sense is that, at the end, we’re supposed to think that Mulder’s life does have meaning. (Or rather: his life is worthwhile, which is not _quite_ the same thing, and the difference might be important.) Is that your take on it too?

Rosenbaum: It provides part of an answer, I think. The absurdity, on a meta level, really drives home the idea that the episode wants Mulder to learn, which is that the world is fundamentally incomprehensible and every time you think you’ve figured something out, it’s a sure sign that you haven’t – both Lizard Guy and Mulder are forced to confront a kind of nihilist epistemology where knowledge is ultimately impossible: you can’t ever know everything – maybe you can’t even ever know anything – but you can want to believe.

So if Mulder is judging the value of his life in terms of the knowledge he gains or disseminates to others, it’s going to be a failure.

BUT if he judges his life’s value by the moral connections he makes with others, there is value. Moreover, if he judges it by the degree of enjoyment he gets from the work he’s doing, it can also have value. The look on his face as the Lizard Guy turns back to his true form before Mulder’s eyes attests to this: the whole thing is impossible and makes no sense, didn’t further Mulder’s epistemological goals at all, BUT he had an authentic encounter with another sentient being that transformed them both (one more than the other), and the sense of wonder and joy that Mulder gained from that is the reward.

Basically: the truth may be out there, but you can’t have it, so you’d better reassess your priorities if you want your life to have meant something.

Stokes: I agree with you one thousand percent. This episode was a love letter to the monster-of-the-week episodes of the X-Files. Learning the truth behind the central mystery — making progress, in the gnostic sense — is not even on the table here. But joy is, and horror, and affection, and laughter, and the possibility of a genuine encounter with the unknown. So you don’t get to know the unknown: so what? If you did, you wouldn’t care. It wouldn’t be unknown any more. But you get to look the unknown in the eye and take its hand, and have it look upon you in return. That — or rather, a staging of that — is what the show aspired to at its best.

Mulder has to want to find the truth, mind you. If he was depicted as a thrill seeker, poking into the X-Files just on the off chance that he’d get to high-five Bigfoot, that wouldn’t make for good TV. He’d seem too venal. But it’s also important that he keep his sense of wonder. (And that’s what this episode offered us.) If he shoots for the truth and misses, and gets to high-five Bigfoot as a consolation prize, he’s going to be okay with that — and so will we. It’s rad enough.

And actually, the biggest secret of all — the hidden truth that undergirds the entire show, is that high-fiving Bigfoot is actually radder after all. (Shh! You have to promise not to tell!) X-Files as product is the ostensible goal. But the real thrill is in X-Files as process.

Thank you for explaining the Gnostic plot. I think the biggest offenders (if you think gnostic plots are bad) are espionage entertainment. Again the principle plot device is uncovering the secrets of others. The TV show “Chuck” was like this. First it was the Fulcrum then it was this, then it was that. Layers upon layers of secrets that on reflection did not actually act as layers, more like hoops to jump through because characters always have to want something and that something is usually knowledge and there always has to be someone trying to stop them. The recent film “Spectre” felt gnostic as well. **Spoilers** You thought you were going to tie up all the disparate loose ends from the three Daniel Craig movies, but really it is just Blofeld 2.0. Underwhelming. I imagine that many long-form superhero comic stories end up gnostic like this. You thought Rabim Alal was going to be the most interesting man in the world, but really it is just Dr. Doom.

Is the gnostic plot just a lazy way to “go meta?”

Yeah, spy shows have a tendency to do this. (Alias is another good example.) I don’t think gnostic plots are bad, necessarily — they can be really exciting — but they are tricky, especially in serialized entertainment, where you sort of need the plot to keep going indefinitely, leading to reveal after reveal after reveal. (For all its flaws, at least The Da Vinci Code gets to reveal its ultimate mystery and then END.)

I think Spectre and the Dr. Doom example you give don’t quite qualify, though: if the man behind the mask feels smaller and more familiar, you’re frame-shifting in the wrong direction. If it turns out that a man is actually an angel in disguise, that’s a gnostic revelation. If it turns out that an angel is a man in disguise, that’s a Scooby-Doo revelation. (Which is, as you say, underwhelming. Maybe we could just say that these are examples of the gnostic plot done *badly*.)

Yeah, I’d characterize it as the difference between climax and anticlimax, both of which can be done well or poorly.

For example, in Die Hard (SPOILERS), when it is revealed that the criminals are not international terrorists, but are just robbers looking for money, that’s anticlimax. One of the traditionally best uses of anticlimax is in mockery or satire – and that’s what happening here, the characters are mocking misunderstandings of human motivation, assumptions about what people value and why, and an overwrought, overly procedural and inauthentic understanding of the world (which is that most bad guys who say they have high ideals are really just in it for themselves in a very basic way).

And then against that anticlimax, you have all the climaxes brought to the table by John McClain. So there’s an elegant sort of counterpoint going on that’s surprisingly complex.

One of the problems with the kind of anticlimax you’re describing is that it seems to aim at being a climax based entirely off the callback factor – the movie is leeching off of character development and cache it didn’t develop itself, and assuming that it must be so important that it serves as climax relative to other things, but if the expectation from outside the work falls short, then it will be anticlimax rather than climax, which shifts the very shape of the narrative and a lot of the rest of the composition.

Like, you don’t “downgrade” into Doctor Doom, right? That seems obvious. Except even Doctor Doom needs to have it established from time to time why he is important and why we should care. Not doing that at all takes too much for granted and can land with a thud.

Thank you to both of you @Stokes and @Fenzel. I like the differentiation you shared. Bigger/more-mind-blowing = gnostic, and smaller/satirical = anti-climax. Each can be done well or poorly.

Two more things. @Fenzel your comments, “One of the problems with the kind of anticlimax you’re describing is that it seems to aim at being a climax based entirely off the callback factor” reminds me of @Stokes post about the hermunetic nature of the Joker in The Dark Knight. ( https://www.overthinkingit.com/2008/08/12/the-philosophy-of-batman-literary-theory-edition/ )The Joker is more interesting in the The Dark Knight because of all of the audience anticipation expectation and experience with the character through various portrayals in comics, film, and TV. Spectre’s Blofeld reveal falls flat because he has not been in a James Bond movie since Roger Moore was Bond and he was never a super well-developed villain in the first place.

The other idea is that your concluding thoughts @Stokes about the episodes take on Mulder’s experience sounds kind of like where the Coen Brothers leave their characters. Nothing really means anything grand in the philosophical sense and life is bewildering but the day to day living of life, the journey of it can be satisfying.