Deep at its core, The Hunger Games franchise is about the power of propaganda.

Indeed, the series takes its name from the Capitol’s most powerful weapon of propaganda, an annual game of gladiatorial combat aimed at keeping the “Districts in line and under the thumb of the Capitol”. In a previous piece, I explored whether or not the Games really work as a weapon of propaganda. Ultimately, I concluded that they didn’t: because the Games gave a platform to the oppressed, the Games ultimately became a means of starting a revolution, rather than stopping it.

But the Hunger Games aren’t the only method of propaganda in the Hunger Games franchise and the Capitol aren’t the only combatants who use propaganda to further their own ends. Indeed, the final book and movie in the series (Mockingjay) take their name from District 13’s ultimate weapon of propaganda: the Mockingjay. So it’s only fair that I ask: does the Mockingay strategy of propaganda actually work?

First, a note: I’m really only dealing with District 13’s use of Katniss Everdeen as the “Mockingjay” after she is rescued from the arena in the Quarter Quell – i.e. after the start of Mockingjay. Prior to that, Katniss was the symbol of rebellion, and likely the subject of D13 propaganda, but not deliberately – she was mostly trying to survive, and in that struggle she inspired others to rebel against the Capitol.

But after her rescue, she shifts from an incidental subject of propaganda to an active participant in its creation. Though Katniss has personal goals that diverge from those of District 13 and President Coin, she aligns herself with them and consciously assumes the mantle of the Mockingjay in order to create anti-Capitol propaganda pieces.

But does it work?

We should start by tracing the conflict between D13 and the Capitol. At the outset of the series (i.e. in The Hunger Games and at the outset of Catching Fire), the rebellion against the Capitol is much closer to a riot in form – it’s unorganized violence by isolated individuals, largely in the form of symbolic (and hopeless) acts of resistance.

But then, in Mockingjay, the series takes a sharp right turn by introducing District 13, the supposedly destroyed center of the previous rebellion. What’s key is that District 13 is a militarized society, and has the resources to wage a for-real war against the Capitol. The conflict wasn’t just a revolution anymore – it was now a war between major powers, with the Districts in between.

They enlist Katniss, telling her that their goal is to “Show them that the Mockingjay is alive and well – we need every District to stand up to this Capitol.”

And for much of Mockingjay: Part I, this campaign seems largely successful: we see at least two examples of rebellious acts conducted in direct response to the Mockingjay campaign: the lumberjack’s attack on the Capitol’s guards (quoting Katniss’ “we burn, you burn with us”), and the nearly-suicidal attack on the dam powering the Capitol. For those attacks, Katniss clearly plays a role in uniting the Districts against the Capitol, so score one for the Mockingjay campaign.

Does it always matter?

But as the conflict goes on, the propaganda begins to matter less and less: the war turns from a conflict of wills to a conflict of arms. The telling moment is in the bombing campaign conducted by the Capitol against District 13: Katniss is relegated to hiding in a bunker, while President Coin strategizes about high-tech war involving aerial bombers, hidden anti-aircraft guns and long range missile deterrence.

From this moment on, the Mockingjay becomes mostly irrelevant – we care because we care about Katniss, but the war has moved on.

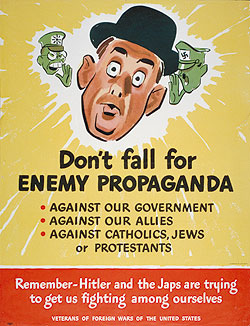

Note that propaganda in its modern form probably first appeared during World War I, when the great powers of Europe were forced mobilize their entire nation in order to prevail in what the perceived to be a life-or-death struggle. Certainly propaganda existed before this time, but the idea of mass produced, mass marketed and heavily financed propaganda was largely a product of the age of industrialized warfare.

And this type of propaganda arguably has at least three different audiences:

- Your own people, in order to motivate them to work harder/volunteer for war/sacrifice more.

- Your enemy’s people, in order to convince them to surrender/fight less/rebel against their own government.

- Other nations, who might be considering either supporting you or supporting your enemy.

For District 13, #2 was the only ever thing that ever really matted (in the sense that the District’s are the “Capitol’s” people).

With respect to #1, District 13 is already a wholly militarized camp: nearly everyone is either under arms or working in some type of wartime industry. While Katniss appears to be popular among the 13-ers, there’s really nothing to show that they work or fight any harder as a result of Katniss’ efforts – indeed, they’ve been working to build an arsenal against the Capitol for decades before she arrived.

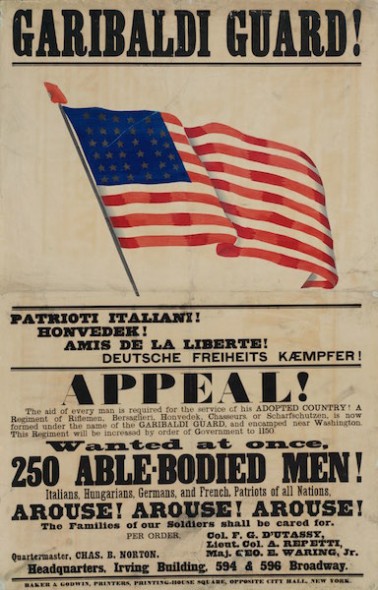

And with respect to #3, as far as we know there are no other nations to be the target of propaganda. This is an important detail to note – shaping the message of a war is quite often aimed quite explicitly at a foreign audience. The recent book Cause of All Nations, for instance, discusses the desperate stakes of the “public diplomacy” campaign waged by the United States and Confederate States during the Civil War – the Union’s pro-democracy message resonated throughout Europe, resulting in tens or hundreds of thousands of new soldiers for the cause; and on the other hand, if Britain, France, or the other “Great” powers of the day had recognized and/or sided with the South, it very well could have made the difference in the war.

World War I was little different – both the Entente and the Central powers were constantly trying to coax foreign powers into either joining the war (if they were leaning that way) or trying to prevent them from coming in (if they weren’t). But in the world of the Hunger Games, there are no foreign powers: there’s no American dough-boys ready to come marching from across the sea to save the Districts.

So the only real target of the propaganda are the individual citizens of the Districts, who need to be induced to side with District 13.

And the occasional citizen of the Capitol, but only if they have really cool haircuts.

But by the time that bombers are above District 13, the Districts have pretty much made up their minds – they’re either all in for the rebellion or supporting the Capitol.

And when you look at it like that, you can’t help but wonder how much Katniss ever mattered – because while she might be good propaganda, the Capitol has terrible propaganda. They do things like raising production quotas under pain of death, and bomb hospitals full of the wounded. Indeed, their propaganda is so consistently bad that District 13 doesn’t even bother to censor it from their own people – they show the Capitol’s propaganda on the internal District 13 television station.

With the Capitol that bad at propaganda, once the war began in earnest between District 13 and the Capitol, it’s possible that Katniss never really mattered at all: the Districts have grievance a plenty against the Capitol, and District 13 would not have had to work hard to find other ways of inflaming the Districts in rebellion.

But with all of that said, what’s important about the Hunger Games isn’t whether or not Katniss wins the war or not – she is, after all, essentially a teenager. We care about her arc because we care about her as a character.

So @Ben Adams, does this mean that “Mockingjay” and the Hunger Games series are generally not good books? Or does this just mean that when we read them we need to approach them interested more in character drama/arcs than in commentary on global politics and propaganda?

I am fine either way personally. I can appreciate them for what they are. I always find though that some of the most interesting commentary from art comes unintentionally or haphazardly.

***Spoiler Alert***

Like the way the book clues you in that Coin is as bad as Snow because of her treatment of Katniss’s style team, that was brushed over and/or left out of the movie. My sister loves the books and was frustrated that such a clear sign or morally corrupt behavior would be left out of the setup for Katniss’s final shot. So the book offers a minor commentary on the problem of semi-fascist conservative leaders who blame societies members for the broader problems of society generally.

The movie, Mockingjay pt 1, was really frustrating. I also loved the books and I especially loved the first half of Mockingjay (not as much the second half). The movie flattened the book. In the book, Katniss has a lot of interesting stuff going on in her head– dealing with PTSD and not wanting to be the Mockingjay because she’s sure it’s going to cause more suffering, death, and destruction. In the movie she doesn’t want to be the Mockingjay because Peeta isn’t around. The movies had a back track record of playing up the very dull (and this is coming from a romance author) love triangle.

I don’t think that the Mockingjay being ineffective as propaganda makes the books bad. The question is really, are the characters in Mockingjay shrewd with their use of propaganda and the answer is sometimes. IRL, people make poor strategic decisions all the time because of limited information, lack of training, or flat out stubbornness. Certainly, the US has made a lot of terrible decisions when it comes to war. If anything, the ineffective nature of The Hunger Games and the propaganda adds to the theme that war sucks for everyone all the time.

The movie suffers from a lack of Katniss’s inner dialog (BTW, haven’t seen either part of Mockingjay, just Hunger Games & Catching Fire.) A big theme of the book is the difference between what’s shown and what’s going on beneath the surface (Katniss playing up her romance with Peeta for the cameras while not actually being all that in to him was the biggest one in the first book, for example), but almost none of that comes across on-screen. Really, how could it without almost voice-over from Katniss, and after enough of that, you’re not making a movie anymore, you’re making a book on tape with pictures.

For sure. Catching Fire was the best adaptation. The movie is at least as good as the book and it balances the idea of what am I feeling vs. what am I trying to convince other people I’m feeling well. Not quite as well as the books, but it smooths some other parts out.

The Mockingjay movies (just got home from pt 2) suffer as much from a general flattening of the characters as they do from the lack of monologue. In the book, Katniss makes a lot of decisions about why she wants to be the Mockingjay and what she’ll do, but in the movie Coin and Plutarch are pretty much controlling her. There’s also way more of her not wanting to be a part of war because hey more people will die, which could have been addressed pretty easily with a few lines of dialogue.

So I hope that other articles are posted about Mockingjay (the movie or book, they are both interesting), but I am afraid there won’t be. So I will ask my question here:

***Spoiler Alert***

President Snow claims, “They are here to destroy our way of life,” as the rebels march on the capital. On the one hand that sounds like a standard PR propaganda line from a dictator who is about to fall, but isn’t it also really, really true?

What I mean is that the way of the life of the capitol, with its decadence and excess being fed by the labor of an entire nation of people, is what the rebels have been actively trying to destroy. Shouldn’t that be some kind of wake up call to the people in the capitol? Why are these rebels so interested in destroying our way of life? What are we doing that is so egregious? Should the rebels be trying to destroy the capitol’s way of life? Is there anything about that way of life that is worth fighting for and protecting? Or are all those who serve the capitol either ignorant dupes or power hungry sadists?

I think the reductionist narrative among the districts would be,”The capitol exploits us so we have a right to fight back.” And the reductionist narrative in the capitol would be, “What privilege are you claiming we have, our lives are hard too. Capitol lives matter.”

The most interesting thing about Snow’s statement is that it seems so straight forward, but on consideration, it actually gets at all the morality and politics in play over the course of the entire series.

Just wondered what you Overthinkers thought about it.

Battle lines in the books seemed pretty evenly split between the disadvantaged vs. advantaged, but I’ve got to imagine there were some poor people in the districts who feared the rebels were going to destroy their ways of life, too. History is full of instances of the oppressed who have internalized the idea that they must stay in “their place” and end up siding with the oppressors over liberators (and of course, of so-called liberators just ultimately dealing more oppression.)

Although in the book the particular break-down of districts and social strata is pretty recent, IIRC about a century, there have to be communities in the districts who really, sincerely believe they are doing their patriotic duty by starving, toiling, serving the greater good and so forth, who fear for the destruction of their way of life the rebels represent. Saying “they’re destroying our way of life” seems like a just vague enough statement that Snow can not only rally the Capitol, but also loyalists within the Districts to oppose the Rebels, or at least to have that potential.

It must be 75 years if the quarter quell is the 75th hunger games.

I think it’s a bit longer. B/c the hunger games were established after the rebellion against the Capitol. That suggests that structure of Panem must have been at least established in theory if not in fact, before the rebellion.

In the books, there’s a real sense that Districts 1 (if it exists. I never understood if the Capitol is District 1 or there’s a separate District 1), District 2 and, possibly District 3, are pretty firmly in the Capitol camp. It’s where the majority of peacekeepers are from, and their economies are heavily reliant on Capitol consumption. I imagine that all districts, with the possible exception of 12, which seems to be literally useless to the Capitol, have a group of residents whose livelihood and relative comforts depend heavily on the Capitol. I’d imagine that these would be reluctant, at least, to bite the hand that feeds. And it wouldn’t be hard for them to justify this somewhat selfish, yet understandable, fear through ideology and patriotism.

It’s been awhile since I read the books. So forgive me if this question is addressed in the novels:

How Did Snow become President anyway? Was there an election with one candidate? Is the Presidency like a Monarchy? Or did Snow seize power from someone else as dictators are wont to do? Given Snow’s age (Donald Sutherland is 80) let’s assume he’s been President for a very long time, so the President of Panen must be Pres for life.

It’s established that Snow seizes power by poisoning a lot of people. The mechanics of this, though, are never explained specifically.

I imagine that, based on how much of Panem is based on the Roman Empire, the choosing of Presidents is similar to those of a Roman emperors. There is a hereditary ruling class from whence all (or mostly all) leaders rise. Within this class there is a system and custom of cutthroat (poison-drink?) politics and competition for power, influence, and military support that determines who ends up at the top and in charge. In essence, any President most likely has to have the support and compliance of a ruling class and the military to not be removed from office (probably by force), but there’s no real formal system of choosing.

I don’t know if this senatorial class exists within the Capitol or if the entirety of the Capitol encompasses this class.

Ok. Thanks for saving me from re-reading! So we can deduce that it is next to impossible for someone outside the Capital to rise to the presidency.

One thing that’s striking about the propaganda on both sides, but especially so on the Capitol’s side, is that it fails to use paranoia as a weapon.

In real rebellions and wars throughout history, one of the through-lines of propaganda is the idea that the enemy has infected the wider population. In the hunger games, the districts have hundreds of spies and collaborators in the capitol. Yet, at no point does Snow incite the citizens to turn on each other, to be on the look out for sedition, to not trust anyone. Considering how terrifyingly effective this tactic has been at controlling a population throughout history, it’s odd that Snow, who clearly has few scruples in maintaining ‘order and peace’ wouldn’t use that weapon. This might be because the Capitol seems to have absolutely zero counterintelligence capabilities. This furthers my longstanding position that Panem is run by a bunch of tyrants who are terrible at being tyrannical, they just suck at it, like a lot.

A more hopeful theory is that perhaps Suzanne Collins didn’t want to tempt people to use such an awful thing by showing in a fiction how effective it really is.

Relatedly, Snow also doesn’t use the rhetoric of treason in his propaganda. He talks about the districts as rebels and savages, but almost never traitors. He never really presents District 13 as essentially foreign. Therefore, he never completely establishes an Us vs. Them mentality that could have brought people to his side, or at least prevented many from taking sides against him.

District 13 is presented as a wayward, angry child that was destroyed and taught its lesson. It’s not presented as the vicious “other’ ready to murder and pillage for its own selfish, essentially alien, goals. Snow, in other words, keeps insisting on framing the rebellion as a Us vs The Part of Us That’s Confused, up until almost the very end.

The more I think about it, the more I hope it was a choice by S.C. to make Panem so inept. After all, if Snow had been an effective tyrant, the idea of Katniss defeating him would be laughable and the series would ring false rather than be hopeful and inspiring.

Here is an idea for you @DeanMoriarty. One of the reasons that Catching Fire was so great was because the dynamic was established that the whole country is balanced on a knife’s edge. We could get into Katniss’s head through the pact she made with Snow to keep the country balancing there.

I think Snow was an inept tyrant because his character was so committed to the idea of his country surviving on the edge. He wanted to do just enough to keep them from going over into rebellion but not so much as to alienate all the suppliers for the capitol.

After the points you brought up in your post, Snow’s government is pretty clearly a work of fiction. Only able to stand so that the protagonist can topple it; not because of reason, logic, or quality management, etc.

It is possible that Snow’s attitude toward the districts is an effect of the propaganda of the Hunger Games working on him. Rather than working to prevent discontent in the Districts, (which it seems the Capitol is content to use force to do), the Games could be in place to shape the attitudes of the Capitol citizens about the Districts.

Given that the Capitol already proved capable of beating the districts in the war, it may be that the Capitol was less concerned with preventing future rebellions and more concerned with the emergence of a political movement within the Capitol advocating for the rights of the Districts. The Districts can object all they want, but only when the Capitol loses the will to maintain the current order through force does the political and economic system face an existential threat.

The Capitol pits the citizens of the districts against each other in fights with archaic weaponry in wilderness areas, which reinforces the idea of the citizens of the Districts as savages who are therefore not worthy of full citizenship. The Hunger Games even include audience participation by attending the public events and sponsorship which gets the Capitol Citizens to emotionally commit to the Games and their message. Inculcating these attitudes keeps the citizens of the Capitol from identifying with the citizens of the Districts and advocating for expanding their rights.

But, of course, this sort of attitude then informs the way he deals with the Districts when they do start a rebellion, and makes the Capitol less prepared for the technology possessed by District 13.