Our last edition of Reading List was divided in two parts, so it only seems reasonable to combine two into one this time around; also I didn’t have any time to write anything last week, so I’ll do it this week instead.

Fight Club 2 #5

Fight Club 2 #5

Dark Horse Comics

I still have very little idea what’s going on in this comic. That may be deliberate, but it’s still frustrating. Fight Club 2 seems to be undoing so many of the things that the original did that I can only see it, at this so far, as either a kind of parody of the broad misunderstanding of Fight Club, or, on the other hand, a kind of revision or retraction, Chaucer-style, of Palahniuk’s still best-known and most-loved work.

While Sebastian (that’s the protagonist, Tyler Durden’s alter-ego) attempts to infiltrate Project Mayhem (which isn’t easy, since, you know, as far as anybody knows he is Tyler Durden), Marla goes off to the Middle East with some Progeria patients to learn what they can about Tyler’s connection to international terrorism.

I don’t know. It’s absolutely full of callbacks, and it’s only halfway through the series, so maybe I’ll have to wait until the whole thing is finished or maybe I’ll just have to start from the beginning and read them all one after the other. I’m just not getting it, guys.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Casey & April #4

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Casey & April #4

IDW Publishing

This final issue in the Casey & April series makes me think that part of the lull of the last couple of issues might have had more to do with the publisher’s requirement that this (like, I believe, all of IDW’s previous TMNT miniseries…es(?)) be four issues long than with any of the creators’ own ideas. Because this issue has got the same creepy vibe and ponderousness, but it’s also got the kind of deep mythology and action that I’ve been hoping for this whole time.

At the end of their journey, April and Casey are reunited and meet up with the Rat King and his sister, Aka, two members of a pantheon that also, apparently, includes Shredder’s mysterious ally or perhaps puppetmaster Kitsune, as well as – we learn – many other beings, immortals, who ruled the planet millennia ago before humans arose and who seem to have become recently interested in getting it back.

Which is an interesting trope, if not an original one. The strength of this whole series has been Irene Koh’s art, which is beautifully distinctive with just the tiniest requisite bit of manga-influence, as well as Brittany Peer’s gorgeous colours, which are maybe the real star of this book and this issue in particular. The flashbacks to past ages, the various transformations of the immortals, and so on, create a lot of opportunity for vivacity of palette, of which the artists take full advantage.

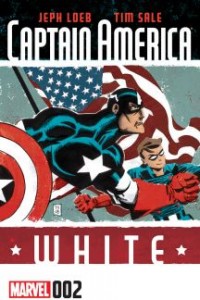

Captain America: White #2

Captain America: White #2

Marvel Comics

The second issue of this series goes back into the themes of loss and recovery that all of latter-day Captain America stories have dealt with, and with which Captain America: White is most concerned. We open four years before Steve Rogers’ first “death” in 1944, when the plane carrying Cap, Bucky, and Nick Fury and his Howling Commandos is shot down over enemy territory and Cap, unconscious, sinks to the bottom of the ocean and out of sight of his comrades. Bucky, of course, is the one who finds and saves him – at the cost of Cap’s iconic, one-of-a-kind Vibranium shield; the shield, strapped to Captain America’s back, is so heavy that it’s weighing him down, making it impossible for Bucky to pull him back up to the surface. Of course we know that he gets the shield back, because it makes the trip into the ice with him four years later. The question is: how?

The story also very effectively uses a number of wrapped flashbacks: we know from Issue #1 that this series is a memory of Cap’s from his moment of rediscovery and revival, which is itself a flashback of decades from the current timeline of the Marvel universe. But by interspersing this story of Cap and Bucky’s first mission with Nick Fury and Company with further flashbacks – to Steve Rogers’ early partnership with James Buchanan “Bucky” Barnes, primarily – the sense of nostalgia in its purest sense, that of yearning for an at least partly unreal past – accumulates like a snowball rolling downhill.

We lose things. Sometimes, we get them back. Captain America more than probably any other superhero symbolizes that. But at the same time, what we get back may not be exactly what it was when it first went astray. The story of what happened between losing something and regaining it gives new contexts and meanings to the lost object – or person – and the circumstances of how our lost things are returned to us also colours what it means to us in the present. And that’s sometimes very different – painfully different – from what it meant to us once upon a time.

So how did Captain America recover his shield from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in 1941? One of those deus ex machina moments that also seems perfectly inevitable in hindsight: Namor the Sub-Mariner. Of course.

Sandman: Overture #6

Sandman: Overture #6

DC Comics / Vertigo

It’s a weird time to be a fan of Neil Gaiman comics. Miracleman is being reprinted and eventually even finished after more than twenty-five years, plus a new volume of The Sandman, generally considered Gaiman’s masterpiece in the comics medium, being serialized at the same time. This isn’t the first new chapter of Sandman since its original run ended at Issue #75 in 1996 (Sandman: The Dream Hunters appeared in 1999, followed by the anthology Endless Nights in 2003), but it is the first one to focus on Dream of the Endless as a main protagonist, and it tells a story that had been hinted at since the very first issue in 1989, when Dream was captured by English magician and held prisoner inside a circle for the better part of the Twentieth Century; the questions was how? As a member of the family of anthropomorphic personifications known as the Endless, Dream is one of the most powerful beings in the universe – not as powerful as his older sister, Death, or, say, Lucifer (yes, that Lucifer), but he’s up there. So how could some nobody hedge wizard from Wych Cross ever possibly trap him in a basement for seventy years? What we already knew was that the wizard in question, Roderick Burgess, was trying to capture Death, not Dream, but that Dream became vulnerable to the spell because he (Dream) was coming back from some mission in a distant galaxy and was super tired.

What was that mission? Why was it so important and so draining? We were never told. Until now.

Now. Almost every issue of Sandman: Overture was really late (Issue #1 was published two full years ago), and for some of those issues almost nothing seemed to happen. J.H. Williams III’s art was breathtaking from the first page and in every single panel, but for most of the time it didn’t seem like the story had a lot of forward momentum.

But we did get some really astonishing things. We met Dream and his six siblings’s parents – whom we never even knew existed before – mother, Night, and father, Time, which we totally should have seen coming (Sandman is absolutely littered with ancient mythologies, and the Greek gods Nyx and Chronos make perfect sense as parents of the Endless) but I for one absolutely did not see coming. For the record: Destiny, Death, Dream, Desire, and Despair take after their mom; Destruction and Delerium look more like their dad.

Anyway, that was a reveal that made me literally gasp when I read it – but that was like a year ago, you know? And the scene where the different versions of Dream come together in the same room (every species in the universe that dreams sees Dream in a different way, and this page had all of them) was dazzling as well, and must have taken Mr. Williams at least as long to draw as Dream was trapped in that basement. But at last, in Issue #6, all the pieces come together and it’s really pretty glorious.

Long story short: five hundred million years ago, a child on a planet in a distant galaxy developed a kind of ontological mental illness called a dream vortex that threatened, if not extinguished, to erase reality itself. It was Dream’s responsibility to destroy the vortex by killing the child, but he hesitated – eventually he did what needed to be done, but despite his siblings’ insistence that he not only kill the child but destroy the entire solar system from which she originated, Dream stopped at just murdering this one kid. Now, because of that, that planet’s sun has become a vortex and been driven insane, and it’s gone too far for Dream to do what he should have done half a billion years ago. The universe is doomed.

Dream’s last-ditch effort to save it – because this whole thing was his fault, really – is to find the one thousand greatest dreamers in the universe, take them outside the universe and set them to dreaming that a little girl five hundred million years ago was responsibly and promptly killed rather than being allowed to linger too long, and then drive that ship of dreamers back into the universe with enough force to make that collective dream convince reality it was true.

Meanwhile we careful readers with long memories get moment after moment of little “a-ha!” as missing pieces from decades-old stories fall into place with the silent subtlety of a black cat in the dark.

I should not have doubted Neil Gaiman.

I was a little worried about the Sandman prequel, since the original series is such a great self-contained epic. But I I should not have doubted Neil Gaiman. Wonderful to hear he stuck the landing. There’s a spot on my shelf for the TPB, right next to all its siblings.