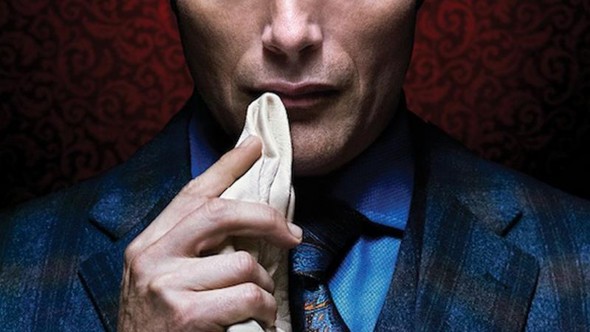

I tend to waffle back on forth over the question of whether or not Thomas Harris is actually a very good writer. I like the books fine, but the movies and the TV show (especially the TV show!) are much better. This suggests that Harris is not making the most of his material. But give the man credit: he invented Hannibal Lecter. The notion of an aristocratic monster is an old one, but Hannibal is a monster with three compelling differences, and although I’m going to focus on only one of these, I’ll go ahead and list all three:

- His violence is always aestheticized. Actually, we can be more specific than that: Hannibal savors the aesthetics of his own violence. He doesn’t just eat people, he eats them with fava beans and a nice chianti. If you look at earlier aristocratic monsters, like Dracula, they tend to be ravening beasts with a surface layer of cultivation. With Hannibal, the cultivation IS the evil, and vice-versa. That’s much creepier.

- Second, he helps the police catch other monsters. Cliche, you say? Well, cliches become cliches because they work, and TvTropes suggests that Lecter is the very first example of a character that works like this. Credit where due.

- Third — and this is the thing I really care about — Lecter is a psychiatrist. He doesn’t just murder people, he messes with their heads. This is, again, much creepier… maybe because psychiatry is creepy to begin with.

I’m not, by the way, saying that there’s anything wrong with psychiatry, that psychiatrists are bad people, or that it’s bad to seek psychiatric assistance. This would be false, and would contribute to the damaging social stigma that already surrounds mental illness. My point is only that that stigma, like it or not, exists.

I think this is basically down to the way that we think about healing and injury. We generally think of sickness as a deviation, a sort of turning away from what a thing actually is or should be. Healing is the process of correcting that deviance. So if my arm is broken, for instance, I’m going to want to straighten it out. Or if I get a cold, I’m going to want to purge my body of that virus. Once the injury or infection is removed, I am healthy — which means I’m back to normal. Now, this is only how we intuitively THINK about the process. In reality, a properly healed break is thicker and stronger than the original bone. But who cares about reality? It’s only our intuitive sense of how healing works that I’m concerned with here, and this intuitive sense requires us to carry around a stylized mental model of what our bodies are “supposed” to be like — what they would heal to, given enough time and enough care.

And this applies to other people just as much as it applies to ourselves. You can’t look at somebody and think that they look wounded without, on some level, imagining their perfectly healthy body would look like. (How else would you recognize it as a wound, right? You’d just be thinking, “Huh, that St. Sebastian guy must have a hard time buying shirts.)

And when we think about mental illness, the same basic model of deviation and restoration applies… except that here, I think, we really only apply it to others.

Won’t Somebody Help Will Graham?

Let’s say that I have a friend named Will.

Hi, Will!

Will is in therapy to deal with his anxiety issues. This is surprising to me, because I don’t think of Will as a particularly anxious person! In my interactions with him, he always seems totally self-assured. A little arrogant, even. But once I learn that he is struggling with anxiety, it’s the most natural thing in the world for me to imagine that his therapy sessions are healing him of that anxiety, by which I mean that they are gradually coaxing his personality back into alignment with my idea of his personality’s ground state. (This attitude is probably not very helpful for my friend, of course, but I won’t lose any sleep over that. Nobody else seems to.)

But how would this work from Will’s perspective? We all have mental models of own minds, just like we have a mental models of our bodies. But we each have a special kind of access to our minds that we tend to deny to others. If Will’s friends are surprised to learn that he is anxious, this is doubtless because he has been hiding his anxiety from them by projecting a false front of arrogant calm. What Jack Crawford thinks of as Will’s real self (i.e. what he would heal back to), Will thinks of as his fake self. And even if Will shows his anxious side to a few of his closest friends, they’ll never fully understand. They might know about the difference between his private self and his public self, but they can’t feel it like he does.

Does Will think of his anxiety as a deviation from his natural way of thinking? That boils down to something perilously close to “I am not who I am.” It’s one thing if his mind is under the influence of some external force like encephalitis, or psychic driving, or fly agaric. Those all feel like physical wounds. But if he simply IS anxious, at what point does that become part of his self-image? (It’s hard to imagine that if you shook Will awake at 4am and shouted “How are you doing?!” he would answer “Great! Fine!”) At what point does wanting to become less anxious involves a certain kind of self-destruction?

And that’s just from the patient’s perspective. What about the psychiatrists themselves? Do they see their patients as broken things that need fixing? Or as imperfect things that need to be guided towards perfection? Do they see themselves as more akin to medical doctors, or to personal trainers? To repairmen, or to sculptors?

Paging Dr. Freud

Here comes Randall, he’s a berserker. (I am 1,000% convinced this character’s name was a Clerks reference, btw. If you have evidence to the contrary, keep it to your dang self: I’m happy in my world.)

Let’s say a patient comes in and tells you “Doc, I’d like to work on my social anxiety. Oh, by the way, just because it will probably come up, I fantasize about turning into a bear and tearing people apart. Like, all the time. But I’m fine with that. Please leave my fantasies alone.” Do you try to make the fantasies go away? If so, this means trying to turn the patient into someone he/she doesn’t want to be… is that all right? Presumably you want to make the patient into the best version of herself/himself… but whose best version is that? The patient’s? Yours? Society’s?

I reached out to practicing psychologist and friend-of-OTI Timothy Swann to ask about this, and it turns out I’m not entirely off base in wondering about these issues. He told me that mental health professionals are guided by something called the Recovery philosophy, which is an attempt to help patients reach “their best level of wellness, as they see wellness, in all areas of their life.” So apparently there’s no idealized normal way that the mind is supposed to work, not in the way that an orthopedic surgeon would think of a properly functioning hip joint. What matters is that you are moving in the right direction — as you yourself define it. Which is a reassuring thing to hear — but I do find it interesting that it’s called the Recovery model. What exactly is being recovered? What was lost? And although Recovery seems to have been specifically designed as a humanistic and patient-centered alternative to the bad old ducking-stools-and-straightjackets approach, Tim did point out that there are limits to that impulse. With some patients “risk has to be incorporated into the model somehow… you can’t have recovery and wellness at the expense of someone else’s recovery and wellness.” When it comes to professional ethics, psychologists end up “hammering Bentham and Aristotle together … the Recovery philosophy looks to maximise human flourishing, the greatest amount of eudaimonia for the greatest number of people.” (I think we’ll all agree that this is preferable to hammering Bentham and Aristotle together by holding that it’s fine to blow up the baby strapped to the enemy’s tank as long as you pull the trigger flawlessly. But it’s still a slightly troubling thought.)

Tim also assured me that it wasn’t even possible to use therapy to turn someone into something they don’t want to be. My first response a sort of paranoid flinch. “You sound awfully sure of that,” I thought. “But how would you even know? You could be changing people against their will all the time, as long as the first thing you change is whether they want to be changed or not! They wouldn’t even know you were changing them! I’m on to you, Swann!” And then I realized that this is what I get for basing my ideas about psychiatry on a TV show about serial killers. Hannibal feeds on our darkest fantasies of what psychiatry is like. It makes psychiatrists seem all-powerful, and then makes them seem corrupt. It depicts therapy as a process of destroying the old self in order to make way for the construction of the new self. And then, once we’re good and frightened of anything even faintly smelling of psychiatry, it unleashes Hannibal Lecter to wreak red ruin on our subconscious dreads.

Hannibal as Therapist

The primary object of therapy, as far as Dr. Lecter is concerned, has nothing to do with what the patient would want, or what society would want. It certainly isn’t a type of healing. The idea for Hannibal seems to be to alter his patients as profoundly as he possibly can: the direction of the change doesn’t matter, but only its absolute value. The best version of the patient, in Hannibal’s practice, is the version that Hannibal finds intellectually and aesthetically pleasing, which in some cases ends up looking a lot like a normal therapeutic relationship right up to the point where Hannibal breaks the patient’s neck.

I don’t think I’m just making this up. In the episode Naka-Choko, Hannibal tells Alanna that therapy is like playing the theremin because, without ever touching your patients, you are “guiding them from dissonance towards composition.” The dog, to hide his villainy in plain sight! The natural word to oppose to dissonance would be consonance, moving from sounding bad to sounding good, sickness to health. “Composition,” in a musical context means “a thing that I created.” Signing up for therapy with Hannibal is signing on to be transformed. To a certain degree, this is true for therapy with any doctor — but with most psychiatrists, there’s an unspoken agreement about what sort of transformation you are in for, which is typically made explicit in your first sessions. With Hannibal, no such agreement exists. (Taking the personal trainer analogy again: you can have a conversation about whether you’re more interested in blasting your quads or in frosting your ploits, but the unspoken agreement is that you’re going to get stronger and thinner. As a personal trainer, Hannibal would start the first session by telling you — or rather, not telling you — “We’re going to work on turning you into a giraffe.”)

Hannibal as Transformer

There’s a flip side to this, though, which is that Hannibal himself doesn’t believe in his ability to transform anything at all. He seems to effortlessly transform human flesh into any sort of food, but is there ever a point where Hannibal himself believes that the flesh has become something other than human? When he cooks, is he not commenting with mordant irony on the impossibility of flesh EVER becoming anything else? He seems to be able to make any person he likes into a cannibal — but is he not simply asserting that the social elites that he invites to his parties are cannibalistic to begin with? And when it comes to his psychiatric practice, he doesn’t seem to believe that he can actually transform Will into a killer. At most, Hannibal can bring out the killer-stuff that’s latent in Will’s essence.

The most important line of Hannibal Season 2, bar none, comes at the end of the episode Su-zakana: “I can feed the caterpillar, and I can whisper through the chrysalis, but what hatches follows its own nature and is beyond me.” (And this line is in fact by Thomas Harris, repurposed from a bit of internal monologue in the Hannibal novel. Once again, credit where due.) Here, Hannibal is thinking about Will in the way that parents think about their children, and to a certain extent in the way that artists think about their artworks. And significantly, it’s also very much the attitude that both God and Satan take in the Book of Job. “Hey big guy! I’ve got a fun idea: let’s do something really heinous to Job, just to see how he reacts! It’ll be revealing.” Note that Satan expects Job to alter his behavior, to be transformed… and yet, at the same time, the whole reason they run the experiment is to see what kind of person Job actually has been all along.

Will, to Hannibal, is child, patient, and artwork all in one. And if we start thinking about the relationship of doctor to patient, the relationship of parent to child, and the relationship of artist to artwork as all somehow being the same relationship, Season 2 of Hannibal starts looking much more thematically unified than it might at first glance. The mural killer, James Gray, is an artist — but Hannibal decides that he’s too controlling of his own work. Gray’s magnum opus is meant to be grimly didactic: the eye sees nothing, because there is nothing to see. By stitching Gray into his own creation, as a glint in the great eye, Hannibal makes the image into an open text (for the glint could be a reflection of anything, could it not?), and pointedly reminds Gray that an artist can only control the form of the artwork, not its reception. The beehive killer, Katherine Pimms, is a health care professional — and although she never interacts with Hannibal directly, he would probably complain that she exercises too much control over her patients. There is a critical account of psychiatry according to which the profession isn’t about healing people at all, but just about turning them into good little cogs in the social machine. (I’m not saying this is true, but it’s an idea that’s out there in the world, and it’s certainly what Jack Crawford had in mind when he first sent Will off to therapy.) In this light, consider what happens to Pimms’s victims/patients. They start out as social misfits: medically disabled pensioners without friends or family. She turns them into productive members of society (or rather into caricatures of such). One of them gets turned into a beehive, literally a means of production. The other is found wandering peacefully around in public with the inside of his head missing. Diagnosis: cured! In making these transformations, however, Pimms scrapes away every last vestige of her patients’ original character. (Hannibal would never do such a thing: he wants to know what he can make of you, and if the result is no longer you, he’s overstepped his bounds.) And then for parent child relationships, we can turn to Mason Verger and his father, who, although unseen, is very much an active presence: it’s hard to escape the sense that the elder Verger, through a program of psychological and physical abuse, has warped his son into an all-too-faithful version of himself.

Subtly opposed to all of these is Hannibal Lecter, a monster to be sure, but a monster who respects the limits of being and becoming. Hannibal recognizes three sorts of transformations. First, there is base matter: human flesh. This can be made to look like anything, but it never changes its nature. Second, there are numinous things: people’s minds, works of art, and so on. These, Hannibal can influence and guide… but they are essentially autonomous, and will find their own shape. Hannibal says at one point that the end of the harpsichord piece he is writing “is eluding [him.]” Note that this doesn’t suggest that he needs to invent the ending, rather, he needs to find it. It exists on its own, somewhere out there in concept-space. All that Hannibal can do is stumble across it, and guide it to its destiny.

And finally, there is Hannibal’s greatest creation: himself.

Human After All

It’s easy to let this slip past, because it’s a TV show and people on TV shows are a little theatrical. But I think it says a lot about Hannibal that he’s making this big flamboyant gesture with his fork, and wearing a carnation in his buttonhole, while EATING ALONE.

As Ben Adams has pointed out on this website before, nothing ruins a good villain faster than a traumatic childhood. If you ask me, one of the few authors to ever pull off a serial-killer backstory successfully is, once again, Thomas Harris, not so much with the backstory for Hannibal but with the one that he provides for Francis Dolarhyde in Red Dragon, which works because there is no one inciting incident that “turns him bad.” Instead, there’s a broken system. (Red Dragon is sort of like The Wire in this way, except that the serial killer is real and doesn’t end up ruining the whole fifth season.) Even that much explanation, though, is going to have a humanizing effect. And that’s not really what we want for Dr. Lecter, is it?

It’s certainly not what the show runners want for him, at least so far. They have wisely chosen to let Hannibal play his cards close to his chest, and as a result, he seems VERY evil. It also seems like Hannibal himself doesn’t want an explanation. Everything about him is calculated (in the sense that you imagine him deliberately deciding to make each choice and take each action), but it’s also all kind of gratuitous (in that his actions serve no broader end). This has the curious effect of making his behavior seem to come from nowhere and lead to nowhere. You don’t get the feeling that killing scratches an itch for Hannibal in the same way that it does for most of the other murderers on the show. I’m sure he would take exception to the idea that he kills out of compulsion: he likely believes that he could stop any time he wanted to. If he wanted to.

Now, of course, that’s just what an addict would say. But we don’t need to agree with Hannibal on this point. We just need to understand that it’s what he believes (or wants to believe) about himself. Hannibal likes to think that he has what is sometimes called “libertarian free will”: for every act that he takes, he believes that he could have just as well done something else. And again, that makes everything that he does SO much worse. It’s not for nothing that some philosophers think that we have to have libertarian free will in order for evil to really exist.

But is Hannibal really an unmoved mover, a self-efficient effect, the agent of his own agency? Maybe not. And the evidence against this, paradoxically enough, is just how badly he wants it to be true. We see this play out at the end of the season two finale. But right at the end there, when Hannibal stabs… the person that he stabs… isn’t there at least a suggestion that he’s doing it because he’s angry at Will for claiming to have changed him? That he’s maybe doing it to prove to Will just how little he’s changed? This in itself is a telling moment. There’s a very clear subtext of “How dare you claim that you made me human? How dare you claim to have had an effect on me! I am the one who has an effect, Skyler Will!” [Stabbity-stabstab-kastab.]

But what’s even more telling is the bit that comes next, where Will, just as he passes out from blood loss, has a vision of a dying stag. The stag is always Hannibal, in Will’s visions. But which facet of Hannibal is supposed to be dying here? In some of the dialogue leading up to the final confrontation, both Hannibal and Will had talked about doing away with Hannibal’s person suit… but it was never Hannibal’s humanity that the stag represented. For Will’s vision to make sense, it has to be the beast that is dying here. And this means that simply by letting Will get to him — Hannibal has proven himself not to be above other people’s influence after all. Everyone else that he has killed, Hannibal killed either like an artist (cultivated and premeditated, beautifully) or like an animal (savage and desperate, without thinking). Here, he kills in a fit of pique. Here, he kills like a person.

Which means that Will has changed him, but not for the better. And not by transforming him into something he’s not, but by scratching his glossy surface to reveal the raw material of which he’s made. And this—despite the elegant and terrible contortions that Hannibal has forced upon himself—turns out to be only humanity: a mean and shabby sort of stuff.