I have a hard time with bad movies.

This wouldn’t sound shocking on its face, except a lot of my friends like bad movies. I don’t mean their taste is worse than mine—I mean they enjoy watching movies that they know, going in, will be bad. Lots of people do, in fact! Mystery Science Theatre 3000 caught on like it did because it tapped into the time-honored tradition of mocking bombs with your buddies. Even if you don’t aspire to that level of wit, kicking back with the latest Steven Seagal movie and a bucket of beers can be a lot of fun.

(I also don’t mean to imply that every movie I like is a critical darling. I love Road House unironically, I watched Taken with only slight reservations, and there’s no David Mamet movie so stiff that I won’t see it in theaters. But I don’t think of these movies as Bad. I acknowledge their faults and their dated aspects, but I didn’t watch them because of those faults)

Growing up has been a long process of unclenching for me, as I’ve tried to relax my youthful snobbery in the name of bonhomie (and yes, I know dropping bonhomie in conversation only hurts my efforts). But since I’m approaching this as a latecomer, I’m still examining the Watching Bad Movies trend. I’m a stranger here. And one of the most fascinating things I’ve uncovered is that, even within the realm of Bad Movies, there’s a line. There’s Bad Enough to Laugh At and there’s Too Bad to Watch.

Pete Fenzel alluded to this on a recent podcast as the “I, Frankenline“—that bright border of quality denoted by the 2014 Aaron Eckhart action-horror dumper, a movie so bad that Fenzel felt guilty suggesting his girlfriend watch it with him. Something about I, Frankenstein crosses the gulf from Bad-Enjoyable to Bad-Depressing.

On a surface reading, this shouldn’t make any sense. If a movie’s Bad, then it’s Bad, full stop. If it’s fun watching Bad Movies, then it should be just as fun to watch I, Frankenstein as Death Bed: The Bed That Eats. But no one holds this to be the case. Even the most decadent Bad Movie Night connoisseurs will acknowledge some Bad Movies as grueling slogs rather than giggly romps.

Some of the mystery owes to the nebulous word “Bad”. “Bad” can mean a lot of things, especially since the 80s. The rest of the mystery comes from the intricate nature of even the most amateur movie. Every movie in the last hundred years, even the worst of them, has dozens of moving pieces: the cast, the story, the dialogue, the cinematography, the editing, the score, the special effects, and so forth. A movie doesn’t need to botch all of those aspects to be considered Bad. Fumbling on one or two of them can cost you the game.

With that in mind, I’d like to examine the phenomenon of a Bad Movie. I don’t think we’ll be able to paint a clear border between Bad-Fun and Bad-Awful in one Internet thinkpiece. But I hope to establish some signposts and start a discussion.

WHERE THE KIDS ARE HIP

First, a quick break and an object lesson.

Funny, right? Hysterical. But why?

This video takes a property that we’re intimately familiar with—the Beach Boys’ “I Get Around”—and changes our expectations. We recognize the singers and the video; it looks like the TV performances of the Fifties and Sixties that we recognize. Everything about this is perfect—except the sound. Not only is the sound off, it is so far off that the clash is absurd. We can’t imagine grown men who make a living as musicians sounding like that. It’s so bad that it’s funny.

This video isn’t a perfect illustration because the sound is deliberately bad as a gag. But what I’m getting at is the difference between bad composition and bad execution.

You can have a movie, or any work of art, that assembles all the expected pieces and then flubs one or two of them. The novel has a bad ending but at least it has an ending. The bridge sounds like a free Garage Band loop but at least there’s a bridge. The dialogue is so corny that we can blame obesity on it but at least there’s dialogue. This is bad execution. Pointing and laughing is an acceptable response.

But a movie that’s badly composed is just frustrating.

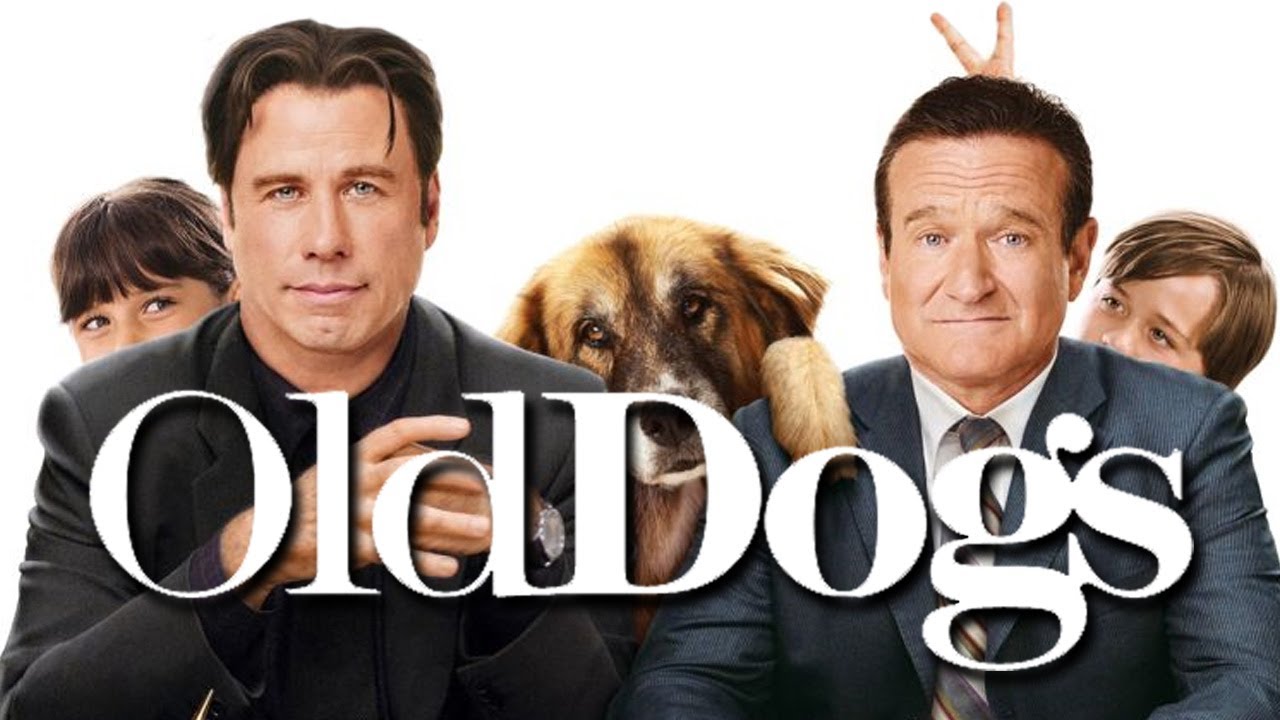

This is a clip from the 2009 aborted Superfund cleanup Old Dogs. Sitting at a generous 5% on Rotten Tomatoes, it starred the late Robin Williams and the breathing John Travolta as hot-shot PR execs who somehow get saddled with two adorable kids for a week. Justin Long appears in the above clip and features prominently in the trailer, but managed to get his name struck from the credits.

If this is your first time watching that clip, I’m guessing you didn’t find it funny. That’s a perfectly normal reaction! This is a bad scene in a famously bad movie, but it doesn’t make us laugh like Underworld: Evolution does. Why?

To truly understand everything that makes this clip bad would take four years at the Tisch School and the soul of a war crimes commissioner. I have neither, but I’ve cobbled together a partial list:

- The scene appears to aim for a slapstick tone with Justin Long accidentally taking Robin Williams’s knuckles to the grill. But the camera lingers for an awful long time on Long’s bloodied face. This isn’t the “harmless” violence of slapstick; it looks like someone genuinely got their teeth wrecked.

- Despite Long’s announcement of “prison rules” ultimate frisbee, play resumes seconds later with neither Williams nor John Travolta seeming especially worried.

- Very confusing editing. As one example: between 0:36 and 0:43, Travolta throws the frisbee to Williams. Williams catches, celebrates for a moment, and is then tackled by an opponent. Another player wearing Williams’ colors is tackled in the same shot, and a close-up (0:43-44) implies that it’s Travolta.So did Travolta just throw the frisbee and then sprint 15 yards to stand next to Williams (in order to be tackled in the same frame)? Or was Travolta tackled off-camera? I’ve watched this sequence more times than the Zapruder film and feel no wiser.

- Joke reactions that lack any punchline. At 0:45, one of the adorable tykes exhorts Williams: “you can get up!” He does and then gets clotheslined by an opponent (in mid-run, despite having last been shown standing still; see bullet re: editing above). The adorable tyke then says, “Never mind.” We already knew that Robin Williams is ironically underqualified to play prison rules ultimate frisbee; what does this girl’s reaction add?

Of course, very few filmgoers have that cinematic grammar, or that level of conscious detachment, when watching an action movie. But we don’t need it. We know it’s bad. It’s confusing and it fails to engage us on any real level.

Old Dogs is the Platonic ideal of a badly composed film. It fails on almost every level a movie can fail on. I want to make fun of it, but there’s nothing to sink my teeth into. All the errors are so fundamental—shot placement, editing, pacing, writing, the lifeless monotony of its lead actors—that they hide in the background, like a garish house that’s also built of rotting timber.

NOW WHAT YOU HEAR IS NOT A TEST

So it’s possible that the line between Bad-Fun and Bad-Awful is whether the movie’s errors are errors of execution or errors of composition. A movie that puts all its pieces in the right place, but chooses a few garish pieces, can be fun to mock. A movie that doesn’t even assemble its pieces properly is just depressing.

But there is another theory that might also explain the same data.

Part of the appeal of watching bad media comes from tribal reinforcement. In getting together with friends to mock Kangaroo Jack, you’re subconsciously saying, “We all agree this is bad, right? None of us think it’s a fine example of the craft?” Making this statement also delivers the inverse: “we are people who know what is good in film.” It re-establishes boundaries and definitions. Every tribe needs a scapegoat, and once in a while the elders need to lay their hands on Blair Witch 2: Book of Shadows and send it off into the desert.

If watching and mocking bad movies is a form of signalling, then it helps if the signal is unambiguous. Everyone needs to point in the same direction at the same time or the choreography fails. If someone brings Pacific Rim to movie night, you run into a quandary: are we watching this to cheer its thrilling fight scenes or to jeer its corny writing? There’s no reason you can’t do both, obviously, but then the movie becomes a point of discussion and a source of intra-tribal jockeying: you’ve got the purists pointing out all the ways the movie could have been better; you’ve got the fans who can watch a movie without pretense, and so forth.

But a movie that everyone agrees is bad unites the tribe. There may be no dispute among matters of taste, but there’s also no dispute that Gymkata has nothing going for it. When the tribe gets to participate in something that unites them against a common enemy, and they get to drink beer and eat popcorn while doing it, they strengthen the tribal bond.

If clarity and strength of signal are what makes a good target, then a Bad-Fun movie needs to be not just bad, but enthusiastically bad. It’s not just a car that struggles in fourth gear; it’s a car that goes careening off a cliff at high speed and explodes in mid-air. It’s not just Timecop; it’s Double Team. Failing with gusto gives an audience clear, unambiguous sign. You can almost choreograph it: as soon as Jeremy Irons opens his mouth in Dungeons and Dragons: The Movie, laugh.

So it’s not as if Old Dogs escapes mockery because it’s not as bad as Kazaam. It’s the same issue alluded to earlier—errors of composition vs. errors of execution—but for a different reason. Movies that fail in execution fail spectacularly. Movies that fail in composition are just a mess.

But the reason watching a movie that fails in execution is fun isn’t because we’re all secret aesthetes, and it doesn’t even really have to do with the subconscious effect of a well-composed film. Movies that fail in execution leave big, bloody handprints all over the walls. Those signals are obvious and easy to latch onto. When you want to unite the tribe, you need the most obvious signals imaginable.

MAN IS A MAGICIAN, AND HIS WHOLE MAGIC IS IN THIS

The size and power of the Hollywood industry has blinded us to the challenge of making a good movie. Making a good movie is hard! Asking someone for two hours of their time and promising they’ll be entertained should be a sacred trust! “The rare, strange thing is to hit the mark,” wrote G.K. Chesterton, “The gross, obvious thing is to miss it.” Yet the studio system has turned the art of the weekend release into such a science that we’re shocked when a movie just doesn’t work.

And Bad Movies should remain shocking, or at least noteworthy enough to make fun of. For a movie to hit the screen, it has to pass through the hands of writers, actors, cinematographers, lighting professionals, sound professionals, costumers and makeup artists, directors, editors, producers, and focus groups. That’s a vast conspiracy of people, any one of whom might nudge a movie farther toward Quality and away from Quagmire. Yet their combined efforts were not enough. The wisdom of crowds failed.

The vast majority of movies released in a given year vanish into mediocrity or the morass of cable. A few ascend to critical acclaim or widespread popularity. And a few are recognized as so heroically bad—refusing to regress to the mean, striding into the undertow with their chins up and flags high, declaring that yes, Dane Cook can headline a romantic comedy—that they call to us. We can’t escape into them, but perhaps we can escape from them, pointing and laughing with our friends in a dimly lit room, and that may be solace enough.

I think the enthusiasm angle has a lot to do with it. “Plan Nine From Outerspace,” a move whose many problems include the fact that one of its actors died part-way through filming and for whom they did a stand-in instead of re-casting the role, also has a clear element of passion to it. The man behind the movie is trying to make a point. He’s doing it badly, especially from a 21st century perspective on the effects, but he cares about the product.

“Snow White and the Huntsman” was, on the other hand, such a bad mishmash of elements and stories, unable to decide on a tone, and just a muddle. The poor CinemaSins guy was just angry by the end of counting all the sins, and I can so see why. There was no point when I thought “Well, at least this one actor or the writer or director actually cares about this movie.” It comes across as just a play for money, without any effort at giving the viewer an enjoyable experience. Even Battlefield Earth, which had been my go-to bad-awful example, had a main character who was TRYING to be in a good movie. (Not enough to get it into the bad-fun category, because I just felt sorry for Barry Pepper the whole time.)

I wonder if it’s somewhat related to suspension of disbelief, as well. Nothing in SN&TH or Battlefield Earth makes me want to shut off the analytical part of my brain. If I can at least get into a sense of “Well, this is kind of a lame movie, but at least they’re trying,” it helps a lot.

Well actually, the Plan 9 story is even more ridiculous than you make out.

• The dead actor in question was Bela Lugosi, of all people.

• He died before principal photography began. Depending on who you ask, the handful of shots in which he appears may have originally been intended for a completely different movie.

• The replacement actor wasn’t Lugosi’s stand-in (who would have at least been the right height). It was the director’s wife’s chiropractor.

• Best of all: the way they got around it was by having the chiropractor wrap Lugosi’s Dracula-cape across his face for every single scene.

First, this made me laugh a lot, so bravo. Second, is there something to the concept of distance when evaluating the I, Frankenline? If a movie is older, and thus distanceable as “of a different time” or we feel less of an attachment or empathy to the people making it, does the line move? If a movie is new, such that it feels a part of “our time” or we can relate in a specific way to what the filmmakers were trying to do but failing at, does the line move?

Also, although I assume logically, it is subjective, is the I, Frankenline different for each person, and why?

I’m an avid bad movie watcher. I count The Happening as one of my favorite movies, I watched Birdemic in theaters (well, theater since it basically just played at Cinefamily for a few nights) and, for me at least, much of the enjoyment comes from the originality of the “bad” movies.

Often, movies that are just good are very similar to each other, because they use tried and tested elements. Great bad movies, are often so ambitious and are the creations of such monomaniacal artists that they end up being different than anything you’ve seen before, or will ever see after.

The Happening for example, is a perfectly well crafted movie from the technical point of view, but is such a ridiculous mess in writing and directing that it becomes this weird mirror image of a perfect movie. Every choic M. Night Shyamalan makes in that movie is the wrong one, but he never second guesses himself, he never walks it back. Instead, the main characters outrun the wind, Mark Wahlberg talks to a plastic plant, and an old woman yells about people eyeing her lemon drink. If that movie had been a “good” movie none of that stuff would have been in it, and the movie would have been just boring and generic.

The other movie I mentioned, Birdemic, is so bad, so weird, so insane, that it’s almost a transcendent experience. While a terrible, terrible movie, it succeeds, despite itself, as a work of art.

This originality, this ability to shock, surprise, baffle, ask ‘why can’t we make a movie like this?’ ‘why shouldn’t this be a movie?’ is what I enjoy most out of bad movies.

I like your metaphor about great bad movies flying off a cliff. But, I think the really really great bad movies, like truly great movies, don’t drive off that cliff on accident. Those movies, those artists, they drive off that cliff on purpose, because they believe they can fly. And sure, we as the audience watch the movie for the moment where it crashes and explodes. But we also watch the movie to share with the movie, for a precious 90-100 minutes, the terror and joy of flying.

I submit for consideration, The Room: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0368226/

This movie is so far below the I, Frankenline that it somehow crosses from Bad-Fun to Bad-Awful and emerges in the vicinity of Bad-Sublime. I have no idea how it exists, but I’m glad it does. A lot of the humor seems to be derived from how fragrantly it transgresses against the typical Holywood veneer of professionalism.

The word you are looking for is the French term ‘nanar’. As discussed in this video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YwQjBC0_2eA

If only there was a book that, in part, discussed this topic. If only…

http://www.mcfarlandbooks.com/book-2.php?id=978-0-7864-9678-5

Sharknado. ’nuff said.

The movie is soooo bad, and yet it’s a hoot to watch.

The movie almost dares the audience to watch, just to see… “How bad can it get?”

So how bad can it get?

Answer:

Sharknado 2

It can always get worse. Which is sort of ironic since the sequel (IMHO) was worse than the original, but surprisingly not better than the original. Weird.

I think there’s a difference between things like “Sharknado” and “Snakes on a Plane” and things like “Plan 9 from Outer Space” and “The Room”. In the former case, everybody involved *knows* that they are in a cheesy “bad” movie and are having fun with the silly concept, but in the latter case, the people involved *thought* they were making good movies — they just had no idea of how to go about doing that.

I wonder if all ‘bad’ movies at some point or another think they’re ‘good’?

‘Troll 2’ is an example of this.

If you watch the documentary of this bad/good movie it appears that some individuals involved actually thought this piece of excrement was very good.

That documentary by the way is called “Best Worst Movie” it’s on Netflix and it’s actually pretty good. It gives some insight about how these trainwrecks get made.