Three, two, one. Let’s jam.

The first post in this series came out in November, 2009. The most recent was in January, 2011, nearly 4 years ago. The entire original run of Cowboy Bebop only took two years—probably the whole production cycle was less than four. So I will understand if you need to take a minute to remind yourself about who these characters are and what I think about them. (Here’s the links: Intro, Sessions 1-5, 6-10, 11-14, 15, 16-18, 19, 20, 21-22, 23, and 24.)

So. The finale. Sessions 25) and 26), The Real Folk Blues. Part of the reason that I was so late with this post is that whenever I sat down to write about these final episodes I’d begin by trying to summarize the plot, and that turns out to be difficult to do in any elegant way. Not an awful lot actually happens, and the things that do happen are sometimes hard to fit together. Still, here’s my best shot. The instigating event that kicks off the action is that Vicious — we all remember Vicious, right? — stages a coup to take over the Red Dragon crime syndicate. One gets the impression that this has been a long time coming. In his first appearance, Vicious assassinated the Red Dragon capo, Mao Yenrai. Was that the start of his power play? In his second appearance, he seemed to be a loyal(ish) enforcer for the three unnamed old coots then running the syndicate… was he working on their orders when he killed Mao? Or did he manage to keep his killing of Mao a secret? We never get to know, and although that’s a curious storytelling choice, it’s quite in line with the way that Cowboy Bebop usually handles character motivations. (It’s also effective because the characters we really care about are similarly out of the loop.)

Anyway, Vicious’s plot seems to fail at first. We see his thugs burst into a richly appointed room and empty their machine gun clips into what turns out to be empty space. Vicious’ creepy bosses had anticipated his coup attempt, and saved themselves by the fiendish and Machiavellian stratagem of… sitting up on a balcony about twenty feet above their old seats. This is dramatic, but so, SO stupid. Let’s accept for the moment that they couldn’t seize Vicious and his men before the coup attempt got off the ground. Why be in the room when that $#!& goes down? Why not be across town? Why not be in the next room over? If you really need to see the expression on his face, why not be twenty feet above the kill zone AND behind a five-inch pane of bulletproof glass?

The stupidity doesn’t end there, though. Not nearly. If Vicious’ men weren’t going to look before they started shooting, or while they were shooting, couldn’t they at least have looked around the room after they finished shooting? And remember, the elders aren’t cape buffalo. They’re decrepit geezers, so withered and dried out that they can hardly stand. What are you gaining by emptying your entire clip? (This last may be the stupidest action taken by any character in the entire run of the series, which is saying a lot. I’m tempted to use it to start an Evil Henchmen’s List modeled after the Overlord List, except that every entry in the list after “#1 – I will not empty my full clip at any character who has dialogue,” would just be “I Will Not Hench” written over and over again. Because really, there’s no percentage in it.)

Anyway, Vicious’s failure has catastrophic consequences for our heroes. The syndicate, operating on the principal of guilt by association, sends a raft of goons to kill anyone who ever had any close ties to Vicious. And since his ex-friend Gren has already run up the flag and joined the sax quartet invisible, this basically just means Spike… and the mysterious Julia.

After this little preamble, we catch up with Spike and Jet in a dive bar, engaged in the traditional dive bar activity of drinking away their loneliness. (You will remember of course that the last episode ended with Faye, Ed, and Ein all leaving the BeBop, and Spike and Jet grimly choking down a basket full of hard boiled eggs.) Neither of them are talking about their emotions of course — they are, after all, Men. So Jet puts on a big show of being happy that Faye is gone, and Spike grimly sucks down his hooch in silence. Just before things threaten to get too real, mafia goons come crashing through the door guns-a-blazing, and Jet catches a round to the leg just to make it clear that our heroes are no longer bulletproof. Oh, it’s a very special episode this time, folks.

“That wasn’t very sporting, using real bullets.”

Spike still has his priorities straight, though:

Yyyyyoink.

Sluuuurp.

This isn’t exactly a callback to the cigarette-lighting scene from “Toys in the Attic,” but it’s sort of ringing the changes on the same joke, right?

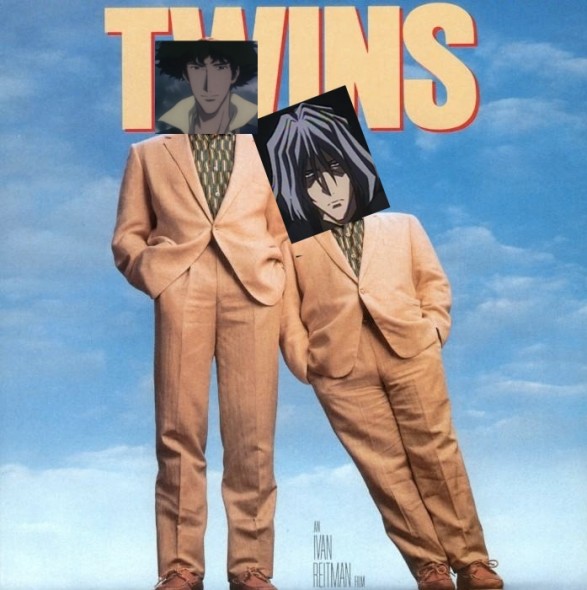

Earlier on in the series, Spike and Jet would have fought their own way out of this. Really, Spike would probably have handled it without Jet’s help. But in this case they only manage to escape thanks to a surprise assist from Shin, an old syndicate buddy of Spike’s. (Shin is probably the weirdest part of the episode. Do you remember Spike’s other old syndicate buddy, Lin, from “Jupiter Jazz”? Shin is his heretofore-unmentioned twin brother. I’m still figuring out what to make of him, actually. He feels totally pointless — which, for this show, means that he probably has a deep symbolic importance that I haven’t cottoned on to yet.)

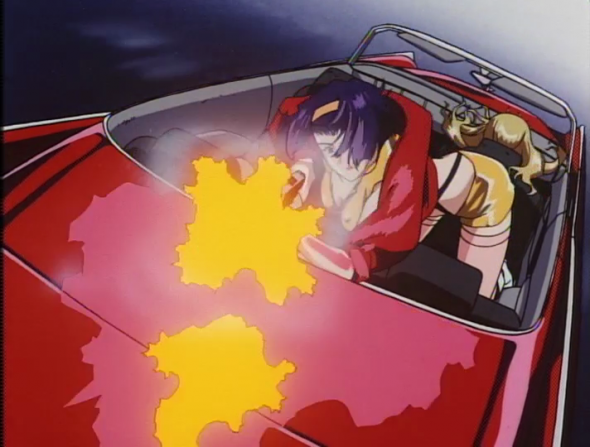

A similar hit squad has been sent after Julia, of course, but she manages to fend them off with an assist from Faye. To which I say… really? Out of the whole solar system, Julia happens to flee down that particular street? And Faye, of all people, steps into the middle of a gunfight to help out a random stranger? But tautly realistic plots were never this show’s stock in trade. This particular coincidence has a job that it needs to do, and it does it: Julia gives Faye a message for Spike; after some vacillation, Faye passes it on; and the lovers are finally reunited (although not before an outer-space dogfight with the mafia that leaves Faye and Jet conveniently hors de combat for the final confrontation). Meanwhile, Vicious activates the second and far more successful stage of his coup attempt. And that’s the end of Session 25.

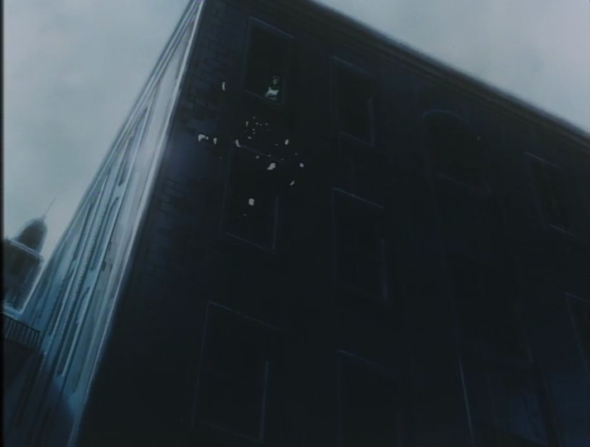

Cowboy Bebop is still doing the formalist thing, by the way. Throughout session 25, there’s a marked tendency to compose the images along a backslash (i.e., “\,” a top-left to bottom-right diagonal), like this:

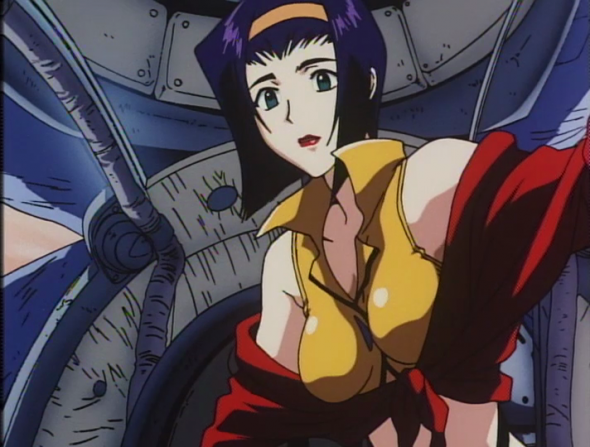

Or like this:

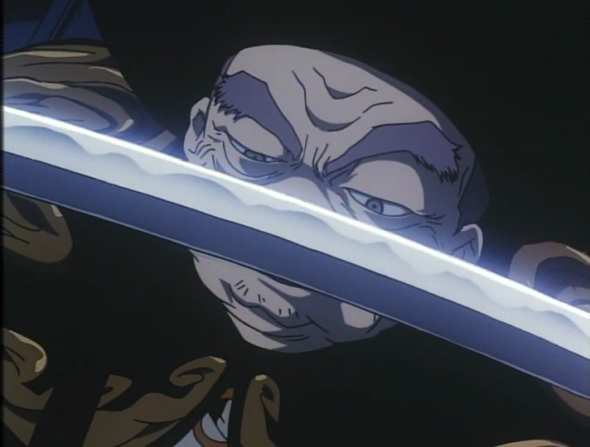

In session 26, on the other hand, the images are built around a forward slash, “/,” diagonals from bottom-left to top-right. Like this:

and like this:

Spoiler alert on that last image I guess. Although not in any meaningful sense of the term.

Session 26 begins with Vicious seizing the reins of power, at which point his first order of business is… trying to have Spike and Julia killed. What I like about this is that it makes the whole “Vicious seems to fail” plot twist TOTALLY gratuitous as far as our heroes are concerned. The consequences for Spike are the same either way! It does, however, play into the show’s broader ethos of failure. It would be shockingly weird, at this stage of the game, for a Cowboy Bebop character to succeed at anything. So instead, they show Vicious failing… then the elders fail right back at trying to have him executed.

Session 26 begins with Vicious seizing the reins of power, at which point his first order of business is… trying to have Spike and Julia killed. What I like about this is that it makes the whole “Vicious seems to fail” plot twist TOTALLY gratuitous as far as our heroes are concerned. The consequences for Spike are the same either way! It does, however, play into the show’s broader ethos of failure. It would be shockingly weird, at this stage of the game, for a Cowboy Bebop character to succeed at anything. So instead, they show Vicious failing… then the elders fail right back at trying to have him executed.

Back at the graveyard, Spike and Julia decide to make a run for it. Well. I should say that she decides that. Her dialogue, in the subtitles, is “Let’s just run away somewhere. Truly escape from this world, and go where no one else is, just the two of us.” Spike doesn’t say anything, but as you can see he looks looks SUPER ENTHUSED about their chances of success.

Good to know that Spike approaches his love life with the same blend of communications skills and emotional honesty that he brings to the table everywhere else. Oh and by the way: “/”

For unexplained reasons, they decide to check in on their old friend Annie on their way out — you all remember Annie, right, the motherly redhead from “Ballad for Fallen Angels”? She’s happy to see them, but she’s already been gut-shot by mafia goons, and lives juuust long enough to make Spike feel really bad about it. At this point, he starts grimly loading a shotgun, and Julia realizes that he’s no longer on board with Plan Run-Off-And-Hide. She gamely vows to stand and fight alongside him, which is touching… and as it turns out, pointless, because Annie’s shop is surrounded, and as Spike and Julia shoot their way out (which they would have to do no matter what their plan was), she ends up getting killed. By a henchman, no less! (Spike kills that guy immediately, of course. “#23 – I will exercise some god damned trigger discipline around the protagonist’s love interest!”) Her entire reunion with Spike lasts less than ten minutes.

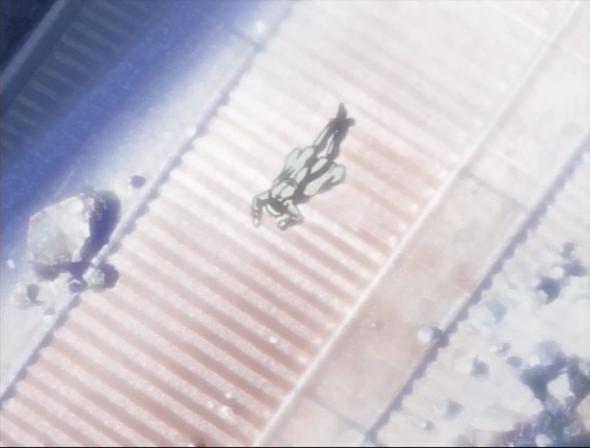

Julia’s death scene is pretty amazing. Let’s talk about the weird temporal hijinks that the animators get up to in this series of shots, starting when she gets hit and ending when she hits the ground.

This takes a total of 26 seconds. Now, there’s nothing weird or innovative about shooting a death scene in slow-motion. But what IS interesting is that there are two different degrees of slo-mo at play here simultaneously. Julia is falling fast enough that her hair trails out behind her like a streamer. Figure it takes about a second of clock time for her to hit the ground. But what about the flock of birds in the background! Birds fly fast, but not that fast, especially when they’re taking off. Probably something like five to seven seconds passes on that plane of the action. And then there’s the series of looks passing back and forth between Spike and Julia’s eyes, which seem less like stretched-out moments of passing time than like little frozen interruptions standing outside of time… it’s cool stuff. And brutal. This is more than just a John Woo homage, is what I’m saying. And I’m sure you noticed that almost every shot in the sequence is laid out on a “/”, right? Right. I should also mention the neat sequence right after this where we see Julia whisper something to Spike as she dies, but there’s no audio on the soundtrack. We’ll talk about this a little more later on — but for now, it’s just worth noting that we DO get to hear what she said eventually. For a normal show, this delayed gratification would be ballsy. For Cowboy Bebop, though, it’s almost conservative… I like to think that in the show’s early running, we would have been left in the dark. But as I’ve mentioned before, these final episodes deal with narrative mysteries in a much more conventional way. (To wit, they occasionally solve them.)

Anyway, if Spike was pissed before, now he’s not happy at ALL. He swings by the BeBop to say his goodbyes, and then launches a full-frontal assault on One Mafia Plaza, or whatever. (Space-age crime syndicates always seem to be located in a big convenient office building — have you noticed this?) Shin shows up again for about five seconds before getting pointlessly shot to death. Spike has his final showdown with Vicious, and just like in “Ballad for Fallen Angels,” they exchange deadly wounds… but this time, the deaths seem to stick. Vicious most certainly dies, at least. Spike collapses ambiguously as he walks back out of the mafia headquarters. His last act is to make a finger-gun into the camera, his last word, “Bang!” And that’s the end of Session 26, and of the series.

“Bang.” (That’s a callback to the end of Session 6, in case you missed it.)

And then he collapses, and the camera zooms out, and out, and then slowly pans up into space — a callback to the end of Session 13.

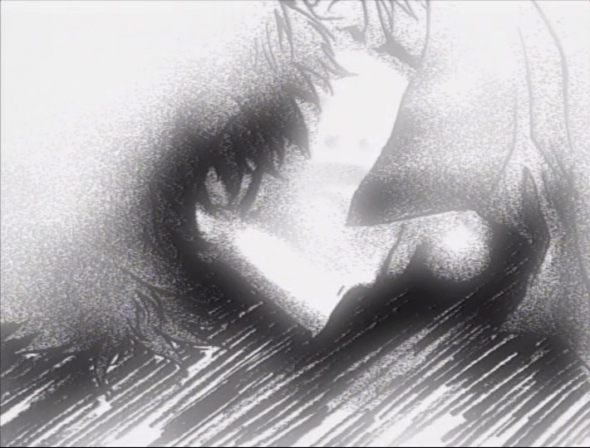

And riiight at the end, it dissolves to this black and white sketch of Spike’s face. Notice how closely this matches the composition of the shot of his body on the staircase! Sometimes I think I’m making these formalist patterns up, and then the show throws something like this at me.

Now, this is actually only about half of the plot of this double episode. There’s also a REALLY important set of flashbacks explaining Spike and Julia’s backstory. I’ll try to summarize these as well, but let me be clear: they’re hella wicked elliptical, so it’s entirely possible that I’m getting some of this wrong. So. Back in the day, Spike and Vicious were brothers-in-arms in the mafia, protegees of the kingpin Mao Yenrai. One day, a mission goes wrong, and Spike gets badly shot up. Julia — a civilian, at this point? — finds him and nurses him back to health. She and Spike fall seriously in love. Eventually, for reasons that are never even hinted at, Spike decides to leave the syndicate, which of course means that he plans to go on the run for the rest of his life. He asks Julia to come along, or more specifically to “escape from this world” with him, making her line to him in this episode a callback. (But it’s simultaneously a call-forward, because this part of the flashback doesn’t happen until after she says it. Is there even a word for that?) This, then, finally explains why Spike had such a soft spot for Katerina and Asimov Solensan in the very first episode of the show: he’s been there, done that, and he knows how it’s doomed to play out.

It’s rare for this team of artists to miss a trick, but I’ll admit that Julia kind of looks like she’s sucking on a lollipop here instead of holding Spike at gunpoint. Also, “/”.

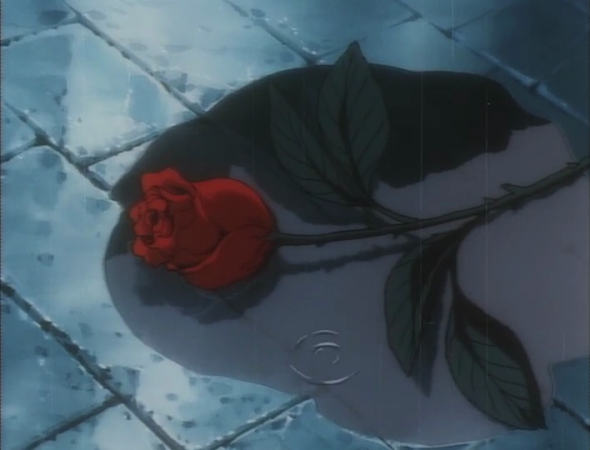

But in the flashback, Spike and Julia never even get a chance to make a run for it. See, Julia also has some kind of relationship with Vicious — romantic? professional? — and when he finds out that she’s planning to run off with Spike, he considers it a betrayal. I have my doubts as to which of them he really felt betrayed by! But we’ll get to that later. The upshot is that Vicious presents Julia with a choice: either she double-crosses Spike and kills him, or else the mafia will kill the both of them. She picks option three, which is to tear up the directions to her rendezvous with Spike, toss the scraps out the window, and then go on the lam on her own. This is another classic Cowboy Bebop moment of “looks cool, is incredibly stupid.” Obviously Julia has the directions memorized — when she and Spike finally meet in this episode, she just tells him to meet her “there.” And obviously Vicious knows the rendezvous point already, or his threat to have them both killed would be hollow. So Julia’s noble gesture accomplishes nothing. Spike shows up at the rendezvous point only to find a mafia ambush waiting in her place — and that ambush is what we see, obliquely, in the little montage with the rose and the greyscale gunfight from the pre-credits sequence of the very first episode of the show! So the real function of Julia throwing the paper out the window is to finally explain the “little floating bits of whatnot” imagery that has surrounded Spike for the entire run of the series:

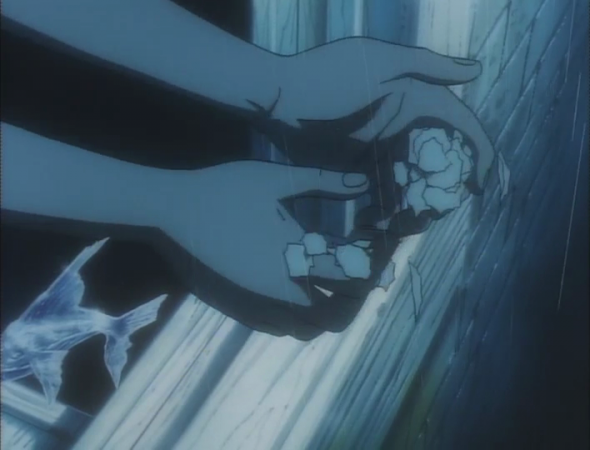

Spike gets pushed through a stained glass window in Session 5. This sequence also draws a line under the symbolism by including —

— a flashback/flash-forward to the scene of Julia tossing the paper out the window (which is totally unexplained at this point: we don’t even see a face to go along with these hands), and then cutting to —

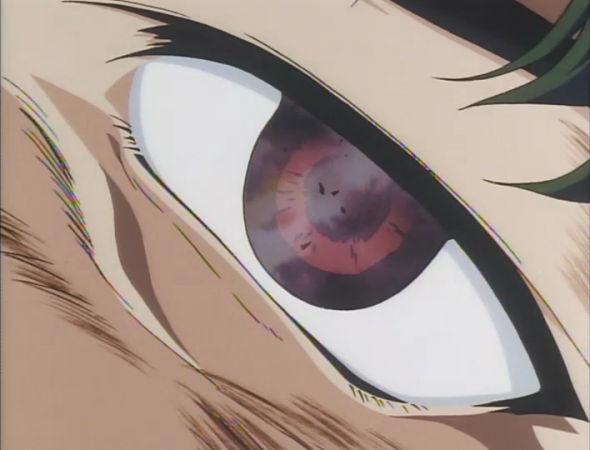

— a closeup of Spike’s eye reflecting, as it were, both sets of fragments at the same time.

And then this is echoed by sparks and ashes, during the confrontation with Wen in Session Six… (This one is weaker, admittedly, because Spike’s not in the frame, but this shot is his POV.)

By little bits of cockpit debris during Spike’s “breathing trick” in Session Seven…

By dandelion seeds — sorry, by Space Dandelion seeds — in the aftermath of Rocco’s death in Session Eight…

By snow at the end of Session Twelve…

And then finally, in session 25, we get back to one that started it all. Only this time we know what’s happening.

(Notice that EXCEPT for Julia tearing up the address, all of these involve Spike having some kind of brush with death — either he nearly dies himself, or he kills someone, or someone he cares about dies.)

That’s as far as the flashbacks take us. Presumably, though, when Spike gets stood up (and, you know… murdered), he feels kind of sad about it, eats a tub of cookie dough ice cream, and then takes up the free-floating life of a bounty hunter so that he has an excuse to keep roaming the solar system in search of Julia. So there you have it: Spike Spiegel, his tragic past.

Of course, a lot is lost by condensing and streamlining it like this. (And this is what I mean about these episodes being difficult to summarize. All the important stuff is in the details.) For instance, the main flashback, which falls in between Jet getting shot and Faye rescuing Julia from the hit squad, is actually spliced into multiple characterizations. Cinematic flashbacks are often — although not always! — tied to the memory of a specific character. The most blatant version of this is the kind of thing you see in Citizen Kane, where you begin with a character in the present saying “It all started on New Year’s Eve, 1929…” followed by a blurry dissolve to the flashback sequence, which in turn leads to a blurry dissolve back to the narrating character as he/she finishes speaking. But you don’t even really need the narration or the blurry dissolve, right? Any time you cut from a character’s face to a flashback, or from a flashback to a character’s pensive face, we assume that the flashback shows us that particular character’s memory of the past. The really cool thing that Cowboy Bebop does here, is that they cut away from Spike to start the flashback, but when they cut back, they cut to Julia. Then they immediately cut to another bit of flashback that Spike couldn’t have known about, and when that’s over, they cut back to Vicious. The memories don’t belong to any one of these characters, but rather to all three of them, which — if we remember the intertwining of memory and subjectivity that the show played with in Speak Like a Child and Brain Scratch — suggests a more fundamental blurring of these characters’ identities. Maybe. (It works better when you watch it than when I try to explain it.)

So that’s cool! But the flashbacks, extensive though they are, still make up only a quarter of the finale’s plot, which means there’s still a quarter unaccounted for. This is devoted to seemingly pointless and disposable scenes where the main characters eavesdrop on strangers at the airport, discuss Hemingway and Aristophanes, and gossip about each other’s love lives. These exchanges are drenched with subtext, and — Cowboy Bebop being Cowboy Bebop — are where the real meat of the episode lies.

Eavesdropping on Strangers at the Airport

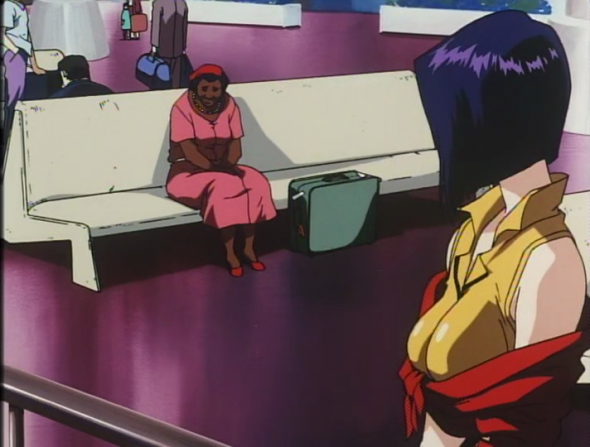

The first of these important unimportant scenes comes right after Spike and Jet get ambushed in the bar. In just a minute, Faye will get dragged into Julia’s chase scene. But before that happens, there’s this seemingly empty vignette with an old lady waiting alone in the airport’s arrival lounge.

This old lady. She doesn’t look so particularly old, now that you mention it.

It’s a pretty short sequence. The woman starts off mumbling to herself: “I won’t go, no matter who comes to pick me up. Never. I don’t want to live a life where I’m always in someone’s way.” Then her son comes running up, saying that he’s been looking all over for her, and that he’s so happy she came, and how he’s going to take care of her from here on out. There’s a cute little joke, here, in that the son turns out to be the host of the Big Shots bounty hunting TV show (the show within the show that got canceled in the previous episode). Faye, looking on, finds this oddly affecting. Then she goes out to her ship in the parking lot, where she gets a call from Spike, who tersely orders her to “stop wandering around so much and just come back” so that she can take care of Jet.

For whatever reason, the animators did amazing work with Faye’s facial expressions throughout Sessions 25 and 26 — not so much in the individual drawings, as in the subtle (or not so subtle) movement between expressions. Here, for instance, check out the transition between her happiness at getting a call from Spike…

… and the cynical pout she forces onto her face once she hears the tone of his voice.

“Don’t just assume that I’m coming back,” she snaps, and hangs up on him. Then Julia comes tearing around the corner in a hail of mafia bullets, and the real plot of the episode picks up again.

The phone call between Spike and Faye is rife with significance, of course. I mean, you saw those facial expressions, right? And holy crap, did Spike just reach out to Faye for help?! But the scene with the Big Shots host and his mother would seem, at first blush, like wasted footage… except that, according to the DVD commentary, lead writer Keiko Nobumoto fought tooth and nail to keep it from getting cut.

Now, it’s possible that this is just a secret message to Nobumoto’s own mother. Think about what the Hot Shots host ends up saying: my show got canceled, I don’t have another job yet, I’d like to move back in with you. Sure sounds like something a Cowboy Bebop writer might want to say to her mother at this point, is all.

But if we assume that there’s more going on here the meets the eye, then the scene is probably there to show us that the barriers that separate us from the people we care about are mainly self-imposed. Faye’s big story arc over the back half of season two has been all about trying to find the place that she really belongs. In Hard Luck Woman, this seemed to lead to a dead end… but could it be that Spike and Jet are really the family she’s been looking for?

Or to come at the same idea from a slightly different angle, we could say that the point of this scene is to show us what a happy ending would look like, if the show was going to have a happy ending. I mean, it won’t. (Spoilers, I guess? If you’ve been paying attention to this series, you should realize that it won’t.) But if it did, this would be it. Heaven, as the show imagines it, is people choosing to live together and take care of each other. And this is here for the asking, if Faye can only bring herself to ask! Or so at least the airport scene suggests.

But towards the end of the second episode, as Spike gets ready to march off to his death, Faye does ask. She holds him up at gunpoint, actually, and begs him not to go. (The blocking and framing of this sequence is a callback to a similar bit in “Sympathy for the Devil,” where she sticks a cigarette in his face instead of a nine millimeter.) Here’s her big emotional speech:

My memory came back. But nothing good came out of it. There was no place for me to return to. This was the only place I could go back to! But now… where are you going? Why do you have to go? Are you telling me you’re just going to throw your life away?

Obviously we don’t want to put too much emphasis on the word “place” here. The BeBop isn’t a place, it’s just a container for the people who travel around in it. It’s Spike that Faye comes back to (and to a much lesser extent, I suppose it’s Jet and Ed as well). Now, it would be possible to think that she’s just being selfish here, trying to make Spike stay so that she doesn’t lose the only home she’s got left. I’m sure that’s part of it. But there’s also a sense in which she’s acting out the little drama that she overheard at the airport, playing the part not of the old lady but of the son. Because Spike is the one who is walking away from the happy ending now. By putting herself on the line like this, Faye is telling him that he doesn’t have to.

Naturally, he leaves anyway. Which means that the real function of the airport scene is to make this even MORE of a kick in Faye’s teeth.

Man, can you imagine what a weird ending it would have been for the show, though, if he’d said yes? “Well, I guess Julia’s not going to get any deader. Let’s go get some waffles.” And then they all just flew off into the sunset?

Aristophanes’s Spherical Hermaphrodites

But Spike doesn’t really have that option. And to understand why, we need to get into Cowboy Bebop’s largely subliminal theory of love and desire. And to do that, we need to talk about spherical hermaphrodites.

One of the most famous pieces of erotic literature — for broad definitions of all those terms — is Plato’s Symposium. (Read it here, because if you google it you’ll probably end up with a 19th-century translation that redacts all the gay stuff.) Like a lot of ancient philosophy, it takes the form of a little play where characters take turns offering up their account of the issue at hand — in this case, Love. And like everything else that Plato ever wrote, it’s meant as a showcase for the views of Plato’s great teacher, Socrates. So the “right” definition of love, in the Symposium, is Socrates’s version, in which pure mental/spiritual love is superior to debased physical love, and when we love people it’s only as part of a process that leads us to us loving knowledge and virtue. (This is a weirder and more complicated concept than what we usually mean when we say “Platonic love,” but you can see the connection. Incidentally, isn’t it weird that some of the ideas we get out of these books have come to be associated with Plato, and some with Socrates? Platonic love, Platonic form… but Socratic dialogue, right? And Socratic irony? Why not Platonic dialogue or Socratic love?)

But there are lots of different accounts of love in the Symposium, and it’s one of the other ones — a bizarre fairy tale that Plato puts in the mouth of the comic playwright Aristophanes — that best accounts for the experience of being in love. According to Aristophanes, people used to be spheres with two heads (arranged back to back), four arms, and four legs. They moved around by turning cartwheels, and reproduced by laying eggs on the ground, “like crickets.” These creatures were beautiful and powerful that the gods grew jealous, and decided to cut them in half to take them down a peg. (So as you can see, this is already making all kinds of sense.)

That conjoined absence-of-ass, though… daaaaang. No wonder Zeus got jealous.

Some of the spheres, Aristophanes tells us, had two male halves (the “children of the Sun”), some two female (the “children of the Earth”), and some one male and one female (the “children of the moon”). All of them, once they were snipped, wanted nothing more than to be whole again, and so they rushed about frantically embracing each other, seeking the half that they had lost. The lucky few who found their other half refused to ever let go. (Implicit in this, I think, is that they don’t know what their other half looks like: remember, their heads were always facing in opposite directions.) Moved by this pitiful spectacle, the gods altered them again, moving their genitals around to their new fronts to enable the version of reproduction that we know and love, thus allowing bifurcated humanity the chance to once again, if but for a moment, become one flesh.

Ridiculous though it is, this account of love feels… somehow… right. (Certainly it feels righter than Socrates’s faintly inhumanly version.) Trying to find a relationship — or even just trying to get a date — often feels less like pursuit of a good thing than like flight from a bad thing. Self help books try to convince us that we don’t really NEED love, and that we have to focus on being whole ourselves before we can have a functional relationship with anyone else. That true love only comes when you aren’t looking for it. And this is all probably true — but the reason that a whole literature exists to convince us of this fact is that, deep down, we don’t believe a word of it. People are essentially unsatisfied, to our very bones we are unsatisfied, and love does seem to fill that gap. (I find it interesting that we instinctively treat love the way we’re supposed to treat food, and vice versa. Imagine a world where it was the other way around. “Listen, Kyle, I don’t think I can date you right now. I don’t have a gnawing hunger for intimacy in my gut that makes it feel like I’m going to die if I spend another day alone… so I can’t go starting a relationship. I don’t want to get love-fat.” Or alternately, “Listen, slice of cheesecake, I don’t think I can eat you right now. I’m hungry, and I respect you too much to eat you when I’m hungry. I need to go work on me for a while by eating this garbage bag full of coleslaw. Once I’m stuffed to the gills, if it’s meant to be, maybe the universe will bring us back together. If and when I cram you down my neck hole, I want it to be because I have no impulse control. Not because my body needs calories to live.”)

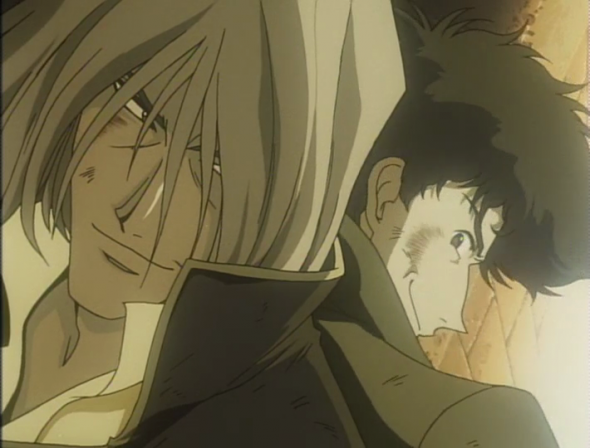

Now, there is nothing very explicit about any of this in Cowboy Bebop. But we’ve already seen something along these lines from several of the main characters. It’s there in the way that Faye, cut off from her past, sort of latches on to the rest of the crew. It’s there in the way that Ed, missing her father, finds a surrogate in Jet. It’s there in the way that Jet, after he’s bloodily separated from his old police partner, finds a replacement in Spike. And then, in “The Real Folk Blues,” when Jet finally forces Spike to explain what kind of hold Julia has over him, Spike says that when he met her, she seemed like “the part of me that I had lost.” We’re explicitly in Aristophanes territory now, folks. And consider this mildly racy screenshot, showing Spike and Julia becoming one flesh. Okay?

Okay, now consider this screenshot.

It shows Spike in his prelapsarian stage, i.e. before the mysterious inciting event that left him drenched in blood, disgusted with Vicious and the syndicate, and desperate to find “the part of himself that he had lost.” Here too, he’s essentially one flesh… but with Vicious, not with Julia! And just like Aristophanes’s spherical proto-humans, he’s happy, powerful, and arranged back-to-back with his partner. Bonus question: who is Spike’s REAL soulmate?

I’m not pointing out homoerotic subtext for the fun of it. (I mean, that too — but not just that.) Let’s pick at this a little more. Imagine there’s a giant mega-character that splits in half, and one of those halves is Spike Spiegel. Doesn’t it make sense that the other half is going to be Vicious? Even by Spike’s own reckoning, they used to share the same blood, which is pretty damn close to being one flesh. We’re not really in Aristophanes territory anymore, though, because it’s hard to imagine that the Spike+Vicious entity is more perfect than Spike is on his own. We’re dealing with decidedly unequal halves, here: a whole that’s less than the sum of its parts.

Vicious, in this instance, plays the role of “the genetic crap that was left over.”

On the other hand, if Julia is Spike’s other half, what kind of hybrid organism did they come from? Well, at this point in the series we know Spike about as well as we ever will. What about Julia? What traits does she bring to the table?

And here our line of questioning comes to a grinding halt. Does Julia even have traits? She’s… blond? She drives fast? (I mean, as depicted on the show she’s mainly just mysterious, but that’s not so much a character trait as it is the absence of any.) Spike sure seems to be charmed by her, but it’s hard to fathom why. Not that she does anything unappealing in the handful of scenes where she actually appears, but nothing about the way she behaves or the way that she’s drawn seems calculated to make the audience as charmed by her as Spike is. And when we consider how vividly and economically Cowboy Bebop has managed to paint its other supporting characters, that’s something of a surprise. When Faye describes her to Jet as “just an ordinary woman,” one begins to suspect that that the writers are hanging a lampshade on something. Even in physical terms she’s subdued. Certainly her hair is striking, and she’s generically easy on the eyes… but think how different her character would seem (and thus, how different Spike’s character would seem, and thus the entire show) if she was drawn as the same kind of cheesecake pinup that Faye always is! I’m glad they didn’t, but it’s an instructive counterexample, and it throws an interesting light on Julia’s actual wardrobe, which is all modest sweater this and flowing trench coat that, almost as if they want to keep as much about her hidden as possible. Hell, even in the sex scene, you see what, her hair and the back of Spike’s head?

And let’s take a minute to consider the very first scene of the episode (which I haven’t talked about yet, because it’s not really important to the plot). It begins with a vocal jazz number and an establishing shot of the planet Mars, followed by a little montage of people walking in the rain. Then Julia walks into her apartment, where she gets a voicemail about how Vicious is making his move on the elders.

Let’s all take a minute to glory in the Zeerust of this image. Spaceflight! Artificial intelligence! Genetically engineered corgis! Aaaaand… a land-line telephone hooked up to an answering machine. The things we turn out not to be able to imagine.

Now, this is the first time that Julia has appeared, actually appeared, in the entire show! She has been this cipher, this gap, in the middle of Spike’s tragic past. Knowing her is surely the key to knowing him, and by this point we are simply dying to know him! And how do the writers use this opportunity to show off who Julia is? They have her do nothing and say nothing. Someone else talks to her for a second, and then we cut to the title card. And what is the sequence used for instead? Well, take a closer look at those images. See the pattern of red dots on monochromatic backgrounds? Huge one for the planet mars, then the umbrella, then the teeny tiny answering machine dot? This isn’t the first time we’ve seen this image. We’ve seen it a lot, actually: throughout the series, Spike’s been having a recurring flashback where we see a bright red rose falling to the ground in the middle of a murky blue-black gunfight. (This is the same gunfight-at-the-graveyard flashback that we talked about a couple of pages ago, by the way.)

This one, remember?

What’s more, the jazz ballad that’s being sung over the top of this is also not quite new. Instrumental versions of this melody have been used throughout the series in almost every episode. (If you go back and read the earlier posts, this melody is the basis for “piano tag” I talked about early on, and it’s also the music-box melody that first shows up in “Waltz for Venus.”) But this is the first time we’ve heard words to it, which makes it seem like this is the real version of the song. My point here is that, rather than provide a small amount of narrative closure by telling us who Julia is, they’ve used the sequence to tie her character in with the non-signifying patchwork of music and imagery that has been building up over the course of the run of the series. So we’ve got this mystery: who is Julia? And rather than tell us anything concrete, they sort of tell us “Oh, Julia is ALL of the other mysteries.” That’s not an answer! But it somehow it fits. Julia isn’t just absent throughout most of the series: she is an absence.

We’ll be coming back to this point. But first: Hemingway.

“Hey, get me marketing on the phone. Yeah. Yeah, it’s about the — no. No, Bob, it really isn’t close enough. No it’s NOT about — no, I think that people WILL notice. [Pause.] They SHIPPED it already! Christ on a crutch, Bob, you’re lucky our industry is still insanely monopolistic, or we’d have a flop on our hands.”

Storytime 1: The Snows of Kilimanjaro

During the first episode, while Jet is recovering from his leg wound, he wakes up in the middle of the night to find Spike sitting in the BeBop’s observation deck. “Have you heard a story that goes like this?” Jet asks, and proceeds to loosely summarize Ernest Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” You can read Hemingway’s version here. Jet’s version goes like this:

“A man injured his leg during a hunt. In the middle of the savanna, with no means to treat the wound, the leg rots, and death approaches. The man got onto the airplane that finally arrived, and there he sees a land of pure white below him. The place glistening in the light was the summit of a snow-covered mountain. The name of the mountain was Kilimanjaro. The man thinks, that was where he was headed…”

“And?” Spike asks.

“I hate this story,” says Jet. “Men only think about the past right before their death, as if they were searching frantically for proof that they were alive.” And then, after a pause, “Turn back. You told me when we first met that you were a man who had already died once. Just forget the past, okay?”

Now, the first thing to say about this, perhaps, is that it’s not a summary of “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” that would make your 10th grade English teacher very happy. It doesn’t indicate that the man is a writer (a thinly veiled author avatar, like all Hemingway protagonists). It doesn’t mention the other main character at all! (I.e., the woman the writer is hunting with, his lover whom he doesn’t love.) And although Jet mentions something about thinking about the past, he doesn’t mention that a full third of the story takes place in flashbacks as the writer relives the loves and adventures of an earlier, more vivid phase of his life. Jet doesn’t even make it explicitly clear that the man dies at the end of the story — that the “airplane that finally arrived” never really arrived, and that the glistening snows of Kilimanjaro were simply the light at the end of the tunnel. (Although I think this is still strongly implied.) Finally, the Bebop version doesn’t even touch on what the story is really about, which is a failed writer coming to terms with his failure. Those crucial flashbacks are all about “the things that he had saved to write until he knew enough to write them well.” He has evidently had some sort of success — the woman, we are told, loves him for his talent — but he has never become the writer that he knew he could be. He blames her for this at first, but eventually he has a moment of clarity:

Nonsense. He had destroyed his talent himself. Why should he blame this woman because she kept him well? He had destroyed his talent by not using it, by betrayals of himself and what he believed in, by drinking so much that he blunted the edge of his perceptions, by laziness, by sloth, and by snobbery, by pride and by prejudice, by hook and by crook. What was this? A catalogue of old books? What was his talent anyway? It was a talent all right but instead of using it, he had traded on it. It was never what he had done, but always what he could do.

I’d never read “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” before I watched Cowboy Bebop, and it took me a couple of pensive subway rides to work out the connection between the half I just told you about (with the flashbacks and the failed literary ambitions), and the other half, the part Jet describes, with the gangrene and the Twilight Zone style fever-dream rescue plane to nowhere. It was this passage that finally made it click for me.

“Do you feel anything strange?” he asked her.

“No. Just a little sleepy.”

“I do,” he said.

He had just felt death come by again.

“You know the only thing I’ve never lost is curiosity,” he said to her.

“You’ve never lost anything. You’re the most complete man I’ve ever known.”

“Christ,” he said. “How little a woman knows. What is that? Your intuition?”

Because, just then, death had come and rested its head on the foot of the cot and he could smell its breath.

“Never believe any of that about a scythe and a skull,” he told her. “It can be two bicycle policemen as easily, or be a bird. Or it can have a wide snout like a hyena.”

Or, as we find out at the end of the story, it can come in the form of a rescue plane. I mean, obviously. That doesn’t even count as an insight. But here’s the thing: I had been interpreting the scene at the very end, with that wonderful lyrical description of Kilimanjaro’s peak, where death turns out to be this kind of liberating embrace, as a happy ending. Yes, Harry dies, but at least he manages to reconcile with the idea of his own mortality. Right? But in retrospect, I think that that’s actually a rather profound misinterpretation, and that Hemingway was making a much nastier point. Forget the peak. Forget the plane, even. Think, rather, about what the plane represents to this specific character. And that’s what death is. Death, for the writer, takes on the form of the possibility of escaping death… just like the thing that made him a mediocre writer was the possibility of escaping that metaphorical death, i.e., the possibility that he could become a great writer at some nebulous point in the future. Dreaming of a fully consummated future, he never bothered to consummate his present. And so he became exactly the sort of writer that he was destined to be: a mediocre one. “And then he knew that there was where he was going.”

Now, read this version of the story back into Cowboy Bebop. Throughout the series, Spike has been holding life at arm’s distance, never really taking joy in anything, never really connecting with anyone. And why? Why, because of hope! Because of the possibility that he could have a real life, and a real human relationship, at some nebulous point in the future with Julia.

This Cowboy Bebop’s final statement on one of its major themes: the “Don’t leave food in the fridge!” plot that I talked about here (and a little more here). In the show’s earlier episodes, living in the past was put forward almost as a virtue, because any old business that you tried to ignore would come back and bite you in the ass. Later on, though (especially in the big Faye arc from the second season) the show got a bit more ambivalent about this. Dealing with past trauma when it comes up is a good thing. But putting your present on hold while you wait for your past to become your future (which is what it turns out that Spike has been doing), is a big no-no. Because living for any future, as Hemingway points out, pretty much ensures that future will never come. And also you will die of gangrene.

But the Hemingway story is kind of bleak. Let’s shift gears and talk about a heartwarming children’s story.

Yaaaaaaay.

Storytime 2: The Cat Who Lived a Million Lives

The big Hemingway sequence from episode 25 has a direct parallel in episode 26, only this time, Spike gets to tell the story. “Do you know a story that goes like this?” he asks, and then recites a truncated version of a popular Japanese children’s book called The Cat Who Lived a Million Lives, by Yoko Sano. You can read a translation of Sano’s story, and see more of her illustrations, here. Spike’s version runs as follows:

There once was a tiger striped cat. This cat died a million deaths and was reborn a million times, and was owned by various people who he didn’t care for. The cat wasn’t afraid to die… One day, the cat was a free cat, a stray cat. He met a white female cat, and the two cats spent their days happily together. Years passed, and the white cat died of old age. The tiger-striped cat cried a million times, and then died. It never came back to life.

“That’s a good story,” says Jet.

“I hate that story,” says Spike. “I hate cats.” And then the two of them burst into a laughter that is slightly desperate, but never less than sincere.

As with “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” a lot of the important details are missing in this retelling of the tale. Easily half of the original story is breezily swept into Spike’s “owned by various people he didn’t care for.” And when you actually read that part of the story, the first thing you notice is that the magnificent tiger-striped cat is a horrible jerk. All of the owners love the cat so much! They’re so sad when he dies! And he doesn’t give a damn about any of them. Now, granted, not giving a damn about the people who love you is a preeeetty standard part of the cat behavioral repertoire. And granted, in abstract terms, if I love you, that does not put you under any particular onus — pace every romantic comedy ever — to love me in return. Even granting all of that, I defy you to read the first section of Sano’s story and tell me that the cat’s not a bastard. (The brilliance of the story’s construction, in this regard, comes in the order that the cat’s various owners are introduced. When the cat is owned by the king, you think “Okay, well, it’s good that he stopped the war.” And with the sailor, the magician, and the burglar, you sort of feel like maybe they weren’t such good owners, because they were putting the cat in a hazardous environment. But then you get to the grandmother, and we’re told “the cat hated grandmothers.” What? And then a child? A child who sleeps clutching the cat and dries her tears on its fur? “The cat hated children.” One gets the impression that Yoko Sano was secretly a dog person.)

But what’s interesting is not the fact that the tiger striped cat a jerk. What’s interesting is the precise flavor of jerk, which is almost exactly the same flavor as Harry in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” Both move through the world without really living, “owned by people they don’t really care for.” (The only difference is that where Harry’s life is already over, the cat’s has not yet begun.) It’s two versions of the same story! And that in itself is interesting, because you would never think from the versions that you actually hear in the show, with all the characterization stripped out, that the stories have anything in common.

But by cutting out the characterization, Cowboy Bebop manages to focus in with great precision on the stories’ religious content. This aspect is more obvious in the Sano, which by any light is recognizable as heretical inversion of the Buddhist idea of reincarnation. The way that saṃsāra is supposed to work — and I’m drawing on a high-school level understanding of the subject, but I think for our purposes here that this is sufficient — is that each soul is condemned to an endless and agonizing cycle of rebirth until it achieves perfect non-attachment, at which point it is finally freed. In Sano’s story, we get the opposite. The cat starts out unattached, and is reborn right up until it attains attachment. This attachment doesn’t bring joy! Or rather, it does, but right along with the joy it brings the pain that in Buddhist metaphysics is the wage of all desire. Attachment suuuuuucks. Sano is refreshingly honest about this — or if you like, refreshingly cruel to children. (She would have gotten along swimmingly with Hans Christian Andersen, don’t you think?) The cat cries and cries, a million times. For years and years. But then when he dies, he is never born again. I think this actually is meant to be a happy ending, of a sort.

And just as Spike’s story is a heretical inversion of Buddhism, Jet’s is a heretical inversion of Christianity. Because flying off to a glistening snow-white island in the sky, and realizing, as you do, that you have been living for this all along, that you never really were a part of the world that you lived in because you always had your sight firmly set on the world you were going to — that’s kind of the point of Christianity. But here it’s presented as a wasted life. And although this aspect is much clearer in the Bebop version, I do think it’s there in the original as well.

Of course, Christianity and Buddhism are rather different, but what they share (along with more or less all other religions) is a contempt for the world we actually live in. And Harry and the Tiger-Striped Cat share that contempt: Harry lives in expectation of the life to come, the Tiger-Striped cat lives a life of perfect detachment from the world and everything in it. Each is, in his own awful way, a perfect religious subject. But here’s the thing — and this is, I think, where each story really becomes relevant to the falling action of Cowboy Bebop — you don’t get to detach from the world unilaterally. The other people that you bump into, as you’re out there just existing and floating from moment to moment, may themselves still be attached to the world. They may be attached to you. And if they are, your self-satisfied zen enlightenment will tear them to freaking shreds. Consider one more passage from “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”:

It was not her fault that when he went to her he was already over. How could a woman know that you meant nothing that you said; that you spoke only from habit and to be comfortable? After he no longer meant what he said, his lies were more successful with women than when he had told them the truth. It was not so much that he lied as that there was no truth to tell. He had had his life and it was over and then he went on living it again with different people and more money, with the best of the same places, and some new ones.

Oh Jesus, poor Faye. Poor Jet, for that matter. (And it’s not like they even have money.)

Calling the Question

When Faye tells Spike that he’s throwing his life away, his response is this: “I’m not going there to die. I’m going there to see if I was ever really alive.” Now, there are multiple ways of reading this. For instance, there’s a high-concept sci-fi reading that has to do with Spike’s robotic eye. Oh yeah, guys, it turns out that one of Spike’s eyes is a prosthetic. Who knew? I have a lot more to say about this than I have room for in this post, actually — but for now, just note that Spike has a robot eye, and that throughout the series it has been glitching out and sporadically feeding him an images of his past life in the syndicate, and especially images of himself getting shot up at the graveyard when he went to meet Julia for the first time. This is really cool, by the way… those repeated monochrome flashbacks of the gunfight with the rose in the puddle, that we keep talking about? Turns out those were actually diegetic flashbacks. That’s bonkers.

So anyway, because of this, we could suppose that Spike literally doesn’t know whether he’s alive, or whether he died in that gunfight. We could be dealing with — WARNING! SPOILER ALERT FOR “AN OCCURANCE AT OWL CREEK BRIDGE” — some kind of “An Occurance at Owl Creek Bridge” type situation here. And this reading does explain some aspects of Spike’s character, like the death wish that I pointed out in one of the previous posts. Because of course the only way to really know that your life isn’t just a hallucination flickering on the eyelids of a dying man, is to die. (This actually resolves all sorts of heady what-if scenarios. Like, if Zhuangzi gets hit by a bus, his dying thought should be “Welp, that settles that. Suck it, dream-butterfly!”) And remember that cryptic, soundless final speech that Julia makes to Spike as she dies? Well, what she said — and note, by the way, that we finally hear this in a flashback from Spike just before he collapses on the staircase — is “This is… a dream.” You can understand why Spike, hearing that, might decide that it was time to settle this once and for all.

But although I think this sci-fi reading is part of what Spike’s line is supposed to tell us, that’s not all that it does. It also essentially calls the question for the audience: was Spike Spiegel really alive? And the answer, sadly, is no. Not really. And it’s not that he’s a walking dead man because he has unfinished business with Vicious, or that he’s got nothing to live for now that he’s lost Julia. He had already stopped living before Julia got shot. He stopped living before we started watching the show, because living means more than just breathing and swallowing food. That’s what the Hemingway and Yoko Sano stories are there to tell us. (And Spike and Jet get this too: I think it’s significant that, while neither of them likes the story that they tell, neither of them has an alternative story to offer.) Probably the clearest way that we see this is in the central Faye-Spike-Julia love triangle. Spike is basically presented with a choice between Faye, a grumpy, messy, self-centered, and deeply human woman, and Julia who — as we noted above — exists purely as the kind of unfulfilled potential that Hemingway was trying to warn us against. Now, of course, if we drag that symbolism back down to the level of character motivations, then it’s not like Spike really gets to choose. You love who you love and that’s the end of it. Nevertheless, this was the test of life… and I could not really tell you that he passed it.

And that’s the note the show ends on. Aggh, what a downer! But folks, we don’t have to stop here. I have SO MUCH MORE to say about this series. (I mean, this episode alone… would you believe me if I told you that this post is trimmed down from a version that’s very nearly twice as long?) So stay tuned.

Early next week, we’ll be making an announcement that I think is pretty exciting. If all goes well, there’s a lot more Overthinking Cowboy Bebop in the works— although it won’t be quite the same format that’s it been in so far. Sign up now to get the announcement by email when we make it.

And if not, well, I’m still pretty damn happy with what this turned into. With the addition of this post, the word count handily breaks 50,000, meaning that it officially qualifies for for NaNoWriMo (although I guess it’s more like NaBloPoWriDecade). It’s longer than The Great Gatsby and Slaughterhouse Five. Most importantly of all, based on a subtitle file for the first episode and some quick back-of-the-envelope calculations, this post makes my write-up of Cowboy Bebop longer, in terms of word count, than Cowboy Bebop itself. (Stage directions included.) Reader, if that’s not Overthinking It, I do not rightly know what is.

IT’S A CHRISTMAS MIRACLE!

Wrong holiday, I know, but this article deserves the full dayenu treatment. Jordan:

If you only gave us a Cowboy Bebop post, dayenu.

If you only made sense of the airport scene, dayenu.

If you only said the thing about Spike’s eye and holy moly how did i never get that before??!!!

If you only made an animated GIF in addition to writing a friggin’ 10,000 word article

And the glorious Twins poster

And the Hemingway-Sano connection

And (best of all) that interlude on the meaning of love in the pre- and post-modern world.

I love this so, so much. In conclusion,

IT’S A PASSOVER MIRACLE!

What was the Dayenu thing about again? I don’t quite follow…

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dayenu

Basically it means, “It would have been enough.” So during Passover the song goes something like, “If God had only brought us out of Egypt, it would have been enough of a miracle for us. If he had only did all the stuff with the plagues, that would have been enough. But then he went and parted the Red Sea, and that alone would have been enough. But then he went and gave us the Ten Commandments…” and yada yada.

I’m saying you shall have no other gods before Stokes.

The thing that always tickled me about Dayenu is that, actually? No: it would not have been enough. If God had led the Isrealites out of slavery in Egypt and then not fed them manna in the desert, ALL OF THEM WOULD HAVE DIED.

10,000 words? But all I needed was a knife!

I would love to see some thoughts on: (1) the falling star: Vicious’s? Spike’s? (2) The meaning of the phrase “you’re gonna carry that weight”. Great work as per usual.

“You’re gonna carry that weight” is a Beatles lyric. Japanese people of a certain age love the Beatles.

To me it’s less about what the words mean than about where they fall.

On the one hand, “You’re gonna carry that weight” comes close to the end of the final Beatles album. And here it’s used again as an ending. So I see it partially as a claim to status by association: this is animation’s Abbey Road. We are the Beatles of animation.

On a smaller scale, though, “You’re Gonna Carry That Weight” comes right after a song called “Golden Slumbers,” suggesting perhaps that now the dream is over — Spike is waking up, real life (or the afterlife) will begin. (But this won’t be fun and games. He still has a burden to carry.)

I’ve always thought that, in addition to those things, it’s a reference to all the characters’ pasts coming back to haunt them, whether they result in closure or renewed conflict. As in, those things you did long ago, those choices you made in another life, you’re going to carry that weight. A long time.

I’ve also always found an aspect of it really comforting. Are you sad that the Beatles broke up? That this is their last album? That this cartoon show is over? That a character has died? Are you sad? Don’t worry. You’re going to carry that weight.

Earlier in the episode when Jet meets with Laughing Bull, he talks about this idea of everyone having a guardian star, and that star falling when the person dies. So it’s symbolic of Spike’s death.

There’s a similar discussion of this earlier on in Jupiter Jazz from the same character, where he talks about the shooting star being the “tear of a warrior” who has finished their battles on the planet and can now find his way to a type of heaven. In that episode it’s probably referring to Gren, but it also ties in nicely with Spike, especially in reference to the story of the cat in the final episode.

“You’re gonna carry that weight” is indeed a Beatles lyrics, the second part of the line being “for a long a time”. So the line at the end of course references Spike now being free of the “weight” of his past life that he’s been carrying with him for the entirety of the show. I think it might also refer to Spike’s death freeing the rest of the Bebop crew from that same weight – by the end of the series, Spike is the only member who hasn’t come to terms with the weight of his past, and I wonder if his death allows the rest of them to finally make a clean break from their own. I find it hard to believe that Faye and Jet go on and continue being bounty hunter partners together after this, for example. Spike was sort of the “glue” that held them together, but that same glue is what kept them from being able to move on with their lives.

Thank you for this. I loved that show many years ago, and in my current decrepit state I forget many things, but most of the points you touch I still remember.

Well, I’m astonished. This project was one of the very things that got me to join your little Overthinking community here, and I’m struck, again, by what a great piece of criticism this whole thing really was.

YESSS!! YOU FINISHED IT! This series was THE reason I started reading/listening to OTI, and I never lost faith that you’d eventually get it done, even after all these years.

Suffice it to say it’s a great article, and leaves me with a lot of food for thought.

Namely, could it be that Cowboy Bebop’s summaries of the Hemingway/Sano stories removed most of the character and storyline not only to focus on the religious content, but because that’s what Cowboy Bebop did with it’s own characters? I mean, sure it also saves time, but with Cowboy Bebop itself we only get the roughest of ideas about what the characters’ back stories and motivations actually are. Like Spike, we can only see patches of reality, never the whole picture.

[Slow clap]

[Second plane of motion where a flock of birds is flying in slow motion, all doing a slow clap]

You deserve all that applause. 10,000 words is a lot to write about anything, especially when you have a life. Much thanks for the baller article, and the dedication it took to finish this series!

(Side note: When I started reading these posts, I was far more into anime, but five years later I feel I’ve kind of moved on. I can only imagine what it must be like looking back on posts you wrote half a decade ago about a show that only takes 12-ish hours to watch that takes place sixty years in the future but was released 16 years ago…Time is weird.)

It’s here! My 4 years of waiting are over!

It’s really funny actually: when I watched this series for the first time back in 2010, I was struck by that scene of Julia throwing white bits of paper out the window in episode 5. I didn’t get what the meaning of it was, and I guess I wasn’t supposed to that early on in the series. But that made me start googling, and my google fu brought me here. So it’s really funny that you mentioned that scene at length in this final installment. I feel like I’ve come full circle. :D

I’m hooked on your podcast now though, so I guess I’m here to stay.

Bebop is one of my favorite shows and I now have the bluray set. I’m going to start rewatching and go through this entire OTI series. I have to wonder though, will Stokes have a completed Samurai Champloo OTI piece in 2019?

Very happy to see this!

I’m not sure that Shin and Lin have much significance beyond what is already wrapped up in the show’s obsession with duality and dopplegangers.

Oh, and \ + / = V

V = Vicious? Symmetry, more doubles. Also, the progress of one type of storyline (Vonnegut’s “a man falls in a hole story”)–things get worse and worse and then the protagonist escapes…to heaven? The / is kind of like a big ramp…

\ + / = X

“it fits. Julia isn’t just absent throughout most of the series: she is an absence.”

“It is your thirteenth birthday, and as with all twelve preceding it, something feels missing from your life. The game presently eluding you is only the latest sleight of hand in the repertoire of an unseen riddler, one to engender a sense not of mirth, but of lack. His coarse schemes are those less of a prankster than a common pickpocket. His riddle is Absence itself. It is a mystery dispersing altogether, like the moon’s faint reflection, with even one pebble of inquiry dropped in its black well. It is the most diabolical riddle of all.” – The title page of Homestuck

“The way that saṃsāra is supposed to work — and I’m drawing on a high-school level understanding of the subject, but I think for our purposes here that this is sufficient — is that each soul is condemned to an endless and agonizing cycle of rebirth until it achieves perfect non-attachment, at which point it is finally freed. In Sano’s story, we get the opposite.”

nirvana (n.)

1836, from Sanskrit nirvana-s “extinction, disappearance” (of the individual soul into the universal), literally “to blow out, a blowing out” (“not transitively, but as a fire ceases to draw;” a literal Latinization would be de-spiration)

“Absence diminishes little passions and increases great ones, as wind extinguishes candles and fans a fire.” – Also the title page of Homestuck

http://www.mspaintadventures.com/?s=6&p=001982

“Some of the spheres, Aristophanes tells us, had two male halves (the ‘children of the Sun’), some two female (the ‘children of the Earth’), and some one male and one female (the ‘children of the moon’). All of them, once they were snipped, wanted nothing more than to be whole again, and so they rushed about frantically embracing each other, seeking the half that they had lost. […] Ridiculous though it is, this account of love feels somehow right.”

Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind offers what I think is a compelling explanation of this story and its strange intuitive resonance.

I’m greatly indebted to you for bringing the sun/moon/earth thing to my attention; an enormous amount of twinspeak centers around gender, in senses ranging from purely biological to purely grammatical, and they’re extremely complex to translate.

[Unrelatedly, writing a guest article for this site has long tempted me, and in two cases I got as far as partial drafts; schizoid personality disorder in Home Alone and Portal II as a metaphor for insight meditation and enlightenment (albeit with one two severe departures from the standard buddhist model). At this point I’m too schizophrenic to finish either one.]

[Disclaimer: I don’t read Cowboy Beep]

Yasher koach. I absolutely loved it, and I’m so glad you finished it. One question. “Turns out those were actually diegetic flashbacks.” I assume I’ll have to wait for the book, but how do we know this?

Peter: I don’t know that we KNOW-know this, but it’s the best way to make sense of Spike’s line about “images of the past.” (And if you go back through the series with this idea in mind, it seems to work.)

Brain Gremlin: don’t get me started on Homestuck.

Adrian: yeah, the doppelgänger thing is where my mind went too. But why rub our noses in that facet right here and right now?

ZeMoose: the system works!

BruceWayneBrady: doubtful, as it would get in the way of the Space Dandy recap that I have scheduled for 2045.

Georgia: that’s an interesting point. I feel like there’s a difference in that Bebop is allusive/evocative, whereas these feel stripped down. Which is not quite the same thing, right? Still, you make an interesting point.

Overthinker#235432: I don’t think Vicious rates a star. But I also don’t think the star necessarily means Spike died, just that his story is over as far as we’re concerned. (Want proof? Check out the sky at the end of Hard Luck Woman.)

SOMEONE’S got to explain Homestuck! If not OTI, then who?

THIS nutjob? http://poorlyplannedcomics.com/?p=1972

Why is the world’s most popular webcomic a taboo subject on the order of flying saucers and 9/11 conspiracy theories? It lies in the middle of the floor of the collective unconscious like a rotting elephant inside a shady-looking rube goldberg machine inside a giant pentagram made of lined-up dominoes.

Andrew is a tiny figure at this point, nonchalantly making the final adjustments to this or that mechanism deep inside the assemblage. Nobody else goes anywhere near the thing, preferring to make giant detours around it while pretending it’s not there.

I fear that without establishing a robust critical perspective NOW, we may not wholly appreciate what Homestuck was even in retrospect.

This guy maybe?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLK7RI_HW-E

It’s not really overthinking it, but I found Spike’s images from the past bit to be perfectly consistent with his character: overly romantic, self-obsessed, and kinda douchey. That is totally the sort of thing he’d say for no reason. ;)

So that the whole big speech is basically just him trying to look cool on his way out the door? Haaa! Love. It.

I came here to echo a lot of the sentiment already posted. Never commented before, but the Cowboy Bebop posts were one of the things that made this website a bi-weekly visit for me, and this was pure excellence. Looking forward to any more thoughts you have on Bebop or anything else for that matter (I mean, within reason).

Ha! And I thought all hope was lost, that this would never get finished. Thank you Stokes! Thank you sooo much.

Great piece of overthinking, as always, really enjoyed reading that. And looking forward to the followup in whatever format it comes… sometime during the next two years…

(Sorry, couldn’t resist :P)

i love your work! İ ve only Just finished this series but i ve read every single well “article” that you ve written For The sessions. the only thing that i didnt get however is the formalist /s and the \s there are far more Of these than the ones you ve already pointed out for example the scene where faye and spike are Having their last conversation The caMera shot changes at some point as if it were located on the ceeling and the pipes make up a / shape. (im reallY terribble at explaining this excuse my inability to Describe) But what does it mean? Or Does it have Any significance whatsoever within the show? ALSO İ ve noticed that when spike says bang and well collapses one of his eyes is closed (due to injury) and i believe that to be his “real” eye. So could it be that him clinging to his past made Him blind to the oppurtunities and the possibilities his future held? And if so does that confirm his death? Also is there any significance to Faye shooting her gun 3 times before he leaves? İs it merely the consequence of supressed agitation and frusturation? Anyway amazing article! İ gotta say i learn more from reading your articles than i ever did at school! ^_^