Given Christopher Nolan’s reputation as a “serious” filmmaker who tries to imbue his movies with a strong sense of believability and realism, it’s no surprise that he would avoid referencing other movies within his movies. There are no such references in his Dark Knight trilogy, and his latest movie, Interstellar, avoids any direct references to science fiction movies (though there are plenty of indirect references to 2001: A Space Odyssey in the movie’s visuals and dialogue). In other words, Cooper doesn’t quip about “boldly going” anywhere during his interstellar voyage, nor does he liken traveling through the wormhole to traveling at “warp speed.”

And yet, in spite of this lack of direct references to movies, Christopher Nolan’s movies actually contain a fair number of stories told within his movies:

- Memento: clues of Leonard’s back story are tattooed all over his body, and he uses those tattoos to try to assemble the entire back story

- The Dark Knight: Alfred tells Bruce Wayne the story of the jewel thief in Burma as a metaphor to describe the threat of the Joker

- Inception: Cobb reveals the back story of Mal’s death, and, more importantly, the architects craft stories through their dreamscapes

- The Dark Knight Rises: Bruce Wayne’s cellmate tells the story of Ra’s al Ghul’s child, who was the only person to ever escape the prison

- Interstellar: schools tell a false story of how the Apollo moon landings were faked, while Cooper tells Murphy the true story of the space program’s accomplishments

There may be other examples in Batman Begins and The Prestige, but those are the ones that I can recall without rewatching all of the movies. The point isn’t that Christopher Nolan always uses this technique, or that he’s unique in this regard. Movies often tell a story within the story to reveal characters’ back stories and otherwise provide exposition and context to the main story being told. Rather, I’d like to examine the usage of the story within the story in Interstellar, both in terms of what is told (the space program’s golden era) and what isn’t told (Star Trek).

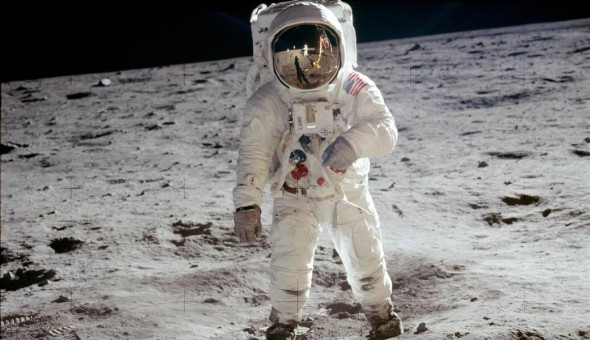

“One small step for man…”

July, 20, 1969: man walks on the moon (holy f**ing sh*t, right?). Cooper tells Murphy the true story of the Apollo Program, which instills in her a love of science that eventually leads her to solving the gravity equation (with some help) and saving humanity. Pretty simple, right? Because we did this amazing thing before, we can do this even more amazing thing in the future.

“…To boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Now, imagine a different version of Interstellar in which Cooper shows Murphy contraband copies of Star Trek movies and TV episodes. Would these be any less inspiring to Murphy than stories of the Apollo Program? Would it be less inspiring to us as an audience, who’s very familiar with both Star Trek and the Apollo Program?

I’m obviously creating a false choice here. It’s totally possible that Murphy watches Star Trek on the dusty laptop when she’s not reading about the Apollo Program in contraband textbooks. But all we see in the movie is how the Apollo Program story leads Murphy to try to solve the gravity equation.

I get why Christopher Nolan chose to go with a true story of space exploration rather than a fictional one. As mentioned before, he values a certain type of realism, and part of that realism is keeping most forms of pop culture outside of the confines of the movie. But in doing so, he inadvertently gives the audience an incomplete perspective on what inspires humans to innovate and reach beyond what’s currently possible. Obviously, all innovation is built on past achievements, but during the period of rapid technological innovation of the past century, it’s clear that speculative fiction–completely imagined future achievements–has played a tremendously important role in inspiring innovation. Stories like Buck Rogers and Star Trek are unshackled by the limitations of what’s already been achieved, and with that freedom, they dare to dream the impossible.

Lest we forget, NASA itself acknowledged the debt that the space program owes to science fiction’s inspiration by naming one of the space shuttles Enterprise. And it’s highly likely that Star Trek is responsible for various scientists’ dogged pursuit of warp drive-like technology, in spite of the long odds of it ever coming to fruition.

Even before there was a thing called Star Trek, NASA was tapping into our shared knowledge of fictional, fantastic tales for inspiration. Mercury; Gemini; Apollo: these were mythic beings with superhuman abilities far beyond what mere mortals could accomplish. Granted, in later years, NASA would pay homage to explorers of the past through names like Magellan and Endeavour, but in those early days, we didn’t look back on past achievements; we dared to dream that we could be gods in the stars.

To be fair to Interstellar, the movie does make a strong acknowledgement of the importance of aspiration:

We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars. Now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.

It’s a great line, and it perfectly captures the tension between the call to greatness in the infinite and the resignation to mediocrity in the cornfields. But it also states an incomplete truth. We don’t just look up at the sky to wonder at our place in the stars. We also look at our TV and movie screens.

Christopher Nolan is of course aware of this. He has repeatedly stated his love of space-based science fiction stories and how they’ve inspired his own filmmaking, and he’s undoubtedly aware of the close relationship between speculative fiction and technological innovation. He walls all of this off from Interstellar, presumably to let the movie’s story stand on its own, but perhaps also out of a desire to see his own movie join that pantheon of great science fiction stories that inspire future generations to dream of the impossible.

In other words, of course the characters in Interstellar watch Star Trek. It’s just that Christopher Nolan’s massive ambition for his movie won’t let us see any of the moments where they talk about it on screen.