This Sunday–October 26, 2014–marks the 30th anniversary of The Terminator, James Cameron’s 1984 classic sci-fi cautionary tale. Here at Overthinking It, we’ve (OK, mostly I‘ve) written dozens of articles analyzing nearly every facet of the movie and its sequels. Hell, I even wrote several hundred words on the guy that stood up Sarah Connor the night the Terminator came to hunt her down.

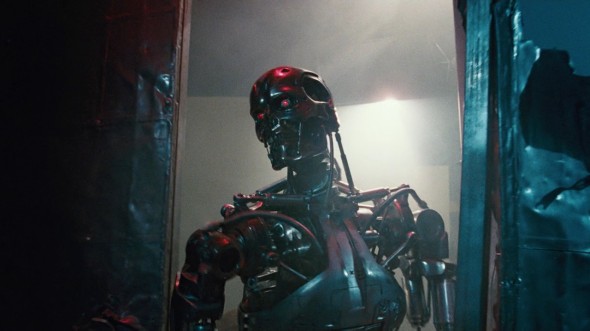

Looking back at this record of Overthinking, though, I realized that one subject has been conspicuously lacking in application of our scrutiny: the titular character of the Terminator. More specifically, the Terminator as it appears in its iconic endoskeletal form:

This manifestation of a nightmarish future apocalypse has maintained a special place in our collective imagination. It’s our go-to illustration of technology gone awry. And rightfully so: it’s terrifying. It’s ghastly. We may take it for granted now, in 2014, three sequels and countless CGI models later. But in 1984, it lumbered to life, with halting stop-motion animation, and 30 years later, it’s still going strong.

But why exactly? What makes the endoskeletal Terminator so iconic?

Let’s start with that skull:

The demonic red eyes are a brilliant artistic touch, but they mostly serve to call attention to the metallic skull that houses those eyes. Apparently the image of a skull activates the same part of the human brain that’s used to recognize faces, which is more than a little creepy. We’re basically hard-wired to recognize human life in an object that only naturally occurs in the context of death and decay. This duality goes a long way towards explaining the recurring usage of skulls in art across a diverse set of societies:

And it’s obviously at play in the movie. We’re slowly introduced to this specific skull throughout the movie as it loses its fleshy exterior:

Alive or dead? Man or machine? Or both? The uncomfortable cognitive dissonance that these contradictions create is entirely intentional, and utterly effective.

From the skull, let’s move on to consider the (endo)skeleton as a whole.

The image of the animated skeleton is not a new one; it’s been with us for hundreds, if not thousands of years, and was particularly prominent in European art beginning with the Black Death in the 14th century. One notable example along these lines is The Triumph of the Dead (1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Older:

Let’s zoom into the detail to appreciate what’s going on here:

I mean, if this isn’t a medieval Terminator attack, I don’t know what is.

But let’s keep digging. The skeletal army isn’t even the most interesting part of this painting. Check out these guys:

One skeleton is playing the hurdy gurdy; the other is riding a horse while holding a lantern and ringing a bell. In other words, they’re mimicking the activity of the living. When we look at these undead creatures, we look straight into the uncanny valley. We see something that closely resemblance ourselves, yet is still horribly twisted and perverted.

And we can’t bring ourselves to turn away. Maybe it’s the aforementioned skull effect; maybe it’s just my own macabre tastes, but I cannot stop exploring the nooks and crannies of this painting. I am completely enthralled by the visual display before me, not in spite of, but because of, its ghastliness.

Likewise with the Terminator. It resembles us in our anatomy and in our sins: it is the product of nuclear holocaust and an abdication of moral responsibility to technology; and it looks like the remains of humans who have died because of those sins. It is ghastly, both in how it looks and what it represents, and yet I cannot turn away from its sight.

But what if it does more than just resemble us? What if it’s more than just a reflection of our present and future sins?

What if the Terminator is no different from the terminated?

This, I think, is the most interesting aspect of the appeal of the endoskeletal Terminator: strip away any human’s exterior, the thin veneer of politeness and morality, and you’re left with a skeleton, a monster. An uncontrollable, unstoppable monster with an unquenchable lust for human flesh. Female flesh, in particular:

This of course is not the central point of the movie. Sarah Connor’s character arc is meant to celebrate the inner strength and goodness of the human spirit. But it is an undercurrent of the Judgment Day story: the worst parts of mankind brought nuclear holocaust upon itself. It’s explored further in the second movie, in which Sarah Connor sheds her own humanity and tries to murder, or rather, terminate, Miles Dyson.

In other words, there’s a Terminator inside all of us, and our daily challenge is to keep it inside and under control.

Has the last thirty years of staring into the red eyes of the Terminator’s skull and contemplating its ghastly familiarity helped? Well, August 29, 1997 came and went just like any other day, and we’re still here. Maybe it did, at least a little bit.

No fate but what we make. Happy 30th anniversary, Terminator.