Scientists estimate that we reached Peak Superhero in the summer of 2008, when “The Dark Knight” sucked the attention of every critic, pundit and sentient moviegoer into its inky nexus. … The genre, though it is still in a period of commercial ascendancy, has also entered a phase of imaginative decadence.

A.O. Scott, “Review: The Avengers,” The New York Times, 5/3/2012

Have we reached Peak Superhero? Maybe, but it’s too early to tell without any solid indicators of a decline in superhero movie production, quality, or audience.

Mark Lee, “Have We Reached Peak Superhero?” Overthinking It, 7/31/2012

Even as they dominate the box office, comic-book movies are approaching a moment fraught with peril. If one definition of a bubble is that everybody with an investment to protect insists that it isn’t a bubble, then we should probably take as a warning the breezy assertion of Marvel’s chief creative officer, Joe Quesada, that “We’re not the Western … The sky’s really the limit for us, as long as we as a collective industry continue to produce great material.” But let’s give him the benefit of the doubt and try out a more specific definition: A bubble reaches its maximum pre-pop circumference when the manufacturers of a product double down even as trouble spots begin to appear.

Mark Harris, “Are We At Peak Superhero?” Grantland, 5/22/2014

What’s with all the hand-wringing over superhero movies? Why are we so interested in whether or not the genre has “peaked” and is in decline, like oil production or housing prices? The most likely explanation is that commentators are projecting their own genre fatigue onto the general public and are assuming–or hoping–that they share their same sense of “This again?”

But maybe there is something to this idea that the post-2000 superhero movie trends of 3-4 superhero movies per year, boffo box office numbers, and occasional critical acclaim aren’t sustainable. The bottom has to drop out inevitably, right? Sony can’t keep pushing Spider-Man movies out the door and expect moviegoers to remain enthusiastic, can they?

A couple years ago, in response to A.O. Scott’s “peak superhero” comment in the context of The Avengers, I attempted to use statistics to determine if we’d hit some sort of superhero movie peak already. At the time, the answer was basically, “No.” Since then, we’ve accumulated two more years’ worth of data (excluding attendance and critical data on Guardians of the Galaxy, due later this summer), and critics are again talking about “peak superhero” in the context of X-Men: Days of Future Past.

In other words, it’s the perfect time to update the data set to see if there’s any new statistical evidence of “peak superhero.”

In a Way, We Already Hit Peak Superhero. In a Way.

In Part I, I used attendance and ratings data for superhero movies from 1978-2012 to look for evidence of a peak and decline. I didn’t find any convincing evidence of one. But maybe I was looking in the wrong place. This time around, I took a closer look at the data and considered the comic book origins of these movies. Here’s what I found: Peak Superhero already occurred in the 1960’s.

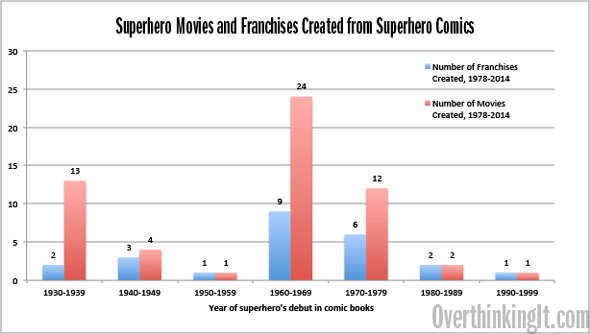

When looking at the corpus of 57 superhero movies from 1978-2014 (including Guardians of the Galaxy) we see that these movies overwhelmingly originate from comics created during the 1960’s: 9 out of 27 superhero franchises, and 24 out of 57 superhero movies.

This should be of surprise to no one: of course our most-beloved superhero stories that have been with us for decades are the ones most often turned into movies. But it’s still valuable to see this expressed with data, as it quantifies the idea implicit in Peak Superhero Theory: that there is a finite supply of A-list superhero characters and stories from which to extract movies, and that this finite supply will lead to the inevitable peak and decline.

So we’ve demonstrated that Peak Superhero does exist, but just from the perspective of their comic-book origins. What about the movies themselves?

Average Opening Weekend Attendance Is Down…But Don’t Read To Much Into That

Let’s take a look at opening weekend attendance in the United States to see if (domestic) audience interest in superhero movies is declining. I’ve bracketed this analysis to just post-2000 releases, both because the first X-Men movie brought about the modern era of superhero movies, and because movie studios only recently placed heavy importance on opening weekend box office numbers.

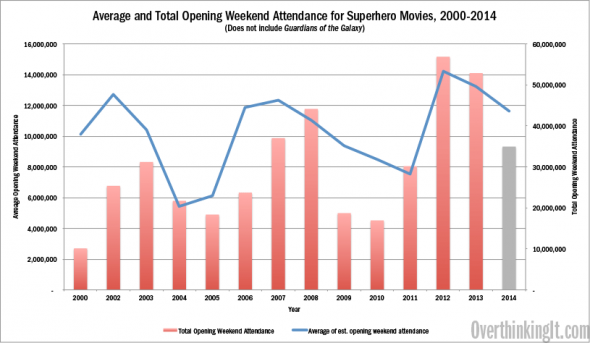

This graph shows average and total opening weekend attendance for superhero movies from 2000-2014:

(Note: opening weekend box office receipts were converted to audience estimates based on Box Office Mojo’s data on historical movie ticket prices.)

Is that a decline from the years 2012 to 2014? Well yes, actually, even considering that Guardians of the Galaxy‘s eventual earnings aren’t factored into the 2014 total. That movie would need a massive opening weekend in the neighborhood of $150 million to get 2014 to the level of 2013, which is basically impossible.

Three data points could be the start of a downward trend…or they could just be statistical noise. Although US opening weekend box office numbers are good proxies for audience/commercial success of movies writ large, they only tell part of the story. A more robust analysis that factors in lifetime box office, foreign box office, and perhaps also share of total box office will have to wait for THE FEW-CHA, but until then, take this for what it is: superhero domestic openings have in fact trailed off from the height of 2012, which saw both The Avengers and The Dark Knight Rises. That year may in fact prove to be a peak, or just another data point on the road to an even bigger year.

Critics Actually Think Superhero Movies Are Getting Better…After They Got Worse

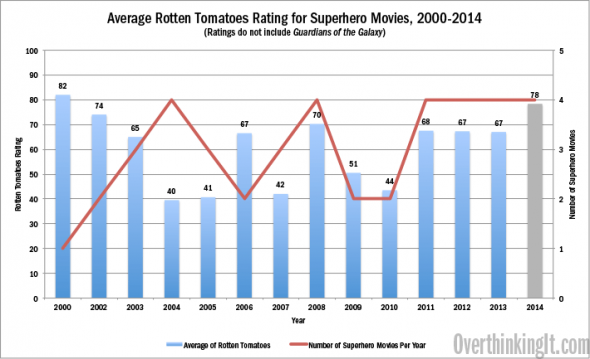

Attendance may be on a slight decline from 2012 to 2014, but quality (as measured by Rotten Tomato ratings) is not. Even with Amazing Spider-Man 2‘s lukewarm critical reception, 2014 is still, on average, one of the best years for superhero movies in the modern era:

Note that 2000’s “average” of 82 is represented by just one movie, X-Men, and that in the ensuing years, there is a bit of a negative correlation between the number of superhero movies produced in a given year and average Rotten Tomatoes scores for that year’s movies. That trend doesn’t seem to hold after 2004, though.

If anything, the data suggests that, after some initial growing pains, movie studies have gotten more consistent about making quality movies. Or at least at avoiding the truly embarrassing mistakes (e.g. Catwoman, 2004). That by itself is neither evidence for or against an artistic “peak” in superhero movies, though. Viewed from another angle, 2008’s The Dark Knight may in fact prove to be a “peak” in the genre, in that it’s the only superhero movie to be honored with an Academy Award for a “prestige” (i.e., non-technical) category. Could it happen again? Absolutely. But perhaps it’s telling that nothing since then has been in serious contention for such an Academy Award.

Franchise Fatigue?

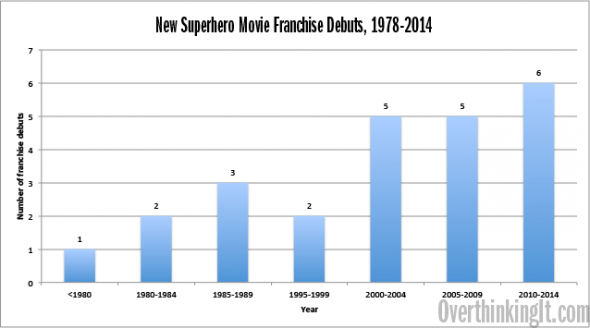

Here’s a new take on the data that wasn’t part of the Part I analysis. Take a look at this graph depicting the release of new superhero movie franchises, which has ticked upwards over the last 15 years:

(Note: categorizing movies into franchises is an inexact science. I put all of the X-Men movies, including the standalone Wolverine entries, into a single franchise, but separated the Avengers from its members as standalone franchises.)

If we’re looking for evidence of unsustainable practices in the creation of superhero movies, we may have found it here. Although movie studios try as hard as possible to exploit A-list superheroes to the greatest extent possible, they also recognize the need to diversify the field to fill in the off-years. Hence the complaints that studios are “scraping the bottom of the barrel” with regards to recent entries such as Thor and upcoming entries such as Guardians of the Galaxy and Ant-Man. Those complaints will only increase if studios keep trying to introduce new characters at the same rate in the coming years. Remember, although the supply of characters isn’t finite, the supply of A-listers absolutely is.

Conclusion

Have we reached Peak Superhero? Yes, we already did, in a way. Peak Superhero Movie? Probably not, and may never, at least in the sense of one-time peak followed by inexorable decline.

Let’s step away from the data for a moment and think about the nature of storytelling with regards to superheroes. The boundaries of superhero movies aren’t drawn by the pool of finite A-list characters and their origin story “requirements.” Instead, they’re drawn by the willingness among moviemakers to take risks with characters and re-imagine them in new and different ways.

Maybe I’m still feeling the warm glow created by Patrick Stewart’s smiling face at the end of X-Men: Days of Future Past, but for whatever reason, I find myself ending Part II on a slightly more optimistic tone than Part I. At this point, I feel comfortable saying that superheroes are an integral part of our cultural landscape at the same level as the stories from The Bible, and as such, they’re here for good, one way or another.

And on that note, let’s return to some data to illustrate this point:

Without being flip or sacrilegious, let me end with this question: if the Jesus story has lasted for 2,000 years, might Batman also last that long?

So what you’re saying is you hope we’ve reached peak “peak superhero”?

Heck, we can go even farther back than Jesus for a long-lived character. What about Hercules, who was basically the Superman of his day? He’s centuries older than Jesus and we’re still making blockbusters about him.

Now I’m trying to think of an ancient equivalent for Batman. Gilgamesh, maybe? He’s a rich asshole who never did anything productive with his power and instead spent all his time wrestling with weirdos in the woods. And he got super-angsty when his youthful sidekick got killed.

What do you mean when you say the Batman story and the Jesus story? If you mean their origin stories they don’t seem that different. Both character martyr themselves for the good of humanity because of their parental relationships.

The big difference is in how the stories are continued. Batman has many many more stories told about him then Jesus. Maybe that’s because there’s a group with a vested interest in no further Jesus stories being told and group with the exact opposite interest with regards to Batman.

The religion of Batman is still regarded as a cult whereas the religion of Jesus is much less ostracized. Maybe there will be fewer stories about Batman when the number of Batman worshipers reaches a critical mass.