[All the content notes and trigger warnings in the world. It’s about Game of Thrones, so, you know. —SM]

Express even a modicum of distaste for the extra-rapiness of HBO’s Game of Thrones and you’ll inevitably hear this kind of comment: “But there was plenty of rape in the Middle Ages! It’s realistic! Deal with it!”

The same thing happens if you comment on the show’s sometimes cringe-worthy racial politics: “There were no people of color in Medieval Europe! I’m being realistic! Deal with it!”

Let’s put aside for a moment that the second comment isn’t even close to true. Here’s a thought-experiment for all the realism-referees in the audience. Seven percent of girls and 3% of boys in grades 5-8 in the U.S. report having been sexually assaulted. Do you want to see between 3 and 7% of the kids on TV sexually assaulted?

Don’t you dare say you’d prefer not to. Don’t suggest it might be exploitative or simply cruel. Don’t ask if such scenes are necessary to the story. ’Cause if you do, here’s what I’ll say: Shut up. It’s realistic. Deal with it.

Maybe you think my analogy is unfair. Fine. A less incendiary one: Have you ever watched Girls? Have you ever seen Lena Dunham strip and have sex with people? Have you ever complained about her nudity? Well, you can’t. Women who don’t look like supermodels take off their clothes and have sex all the time. So stop whining. It’s realistic. Deal with it.

What I’m saying is that appeals to realism are not applied across the board. I have no statistics on the matter, but it seems they’re often used to shut down criticism that comes from “haters,” a.k.a. marginalized people who hope to bring attention to TV’s backward politics. But when a show dares offend the sensibilities of a certain type of fanboy, suddenly we’re not talking about realism anymore. Suddenly the conversation is about what “people” do and do not want to see on their screens.

Apparently more offensive than rape.

But appeals to realism aren’t only used to shut down criticism. They’re also used to damn and to praise. This movie is bad because the science is inaccurate. That movie is good because the period details are spot on. This show is bad because the dialogue is heightened. This show is good because there are no plot holes.

It often makes sense to use these arguments. If you’re judging a work of hard sci-fi, it’s reasonable to put a magnifying glass on its technology and physics. If we’re watching a thriller and a plot hole destroys your ability to suspend disbelief, nothing I say is going to make you like the work. Nitpicking TV and movies for fun is Overthinking It‘s raison d’être, so far be it from me to tell you it’s always wrong.

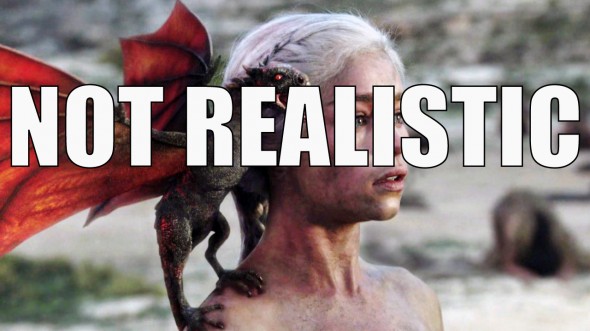

It’s just weird when I enter forums and comment threads about Game of Thrones, and I find myself back in the 1800s, and everyone’s Émile Zola—except this Zola’s applying the rules of naturalism to a story featuring dragons. It’s like everyone got together before the first episode and decided Westeros was a real place and its history real history, and any naysayers are idiots ignorant of the Way Things Were.

It’s bizarre.

It’s equally bizarre when these would-be Zolas apply their rules to works of surrealism. Take those who have burned my dear Hannibal with a dire brand reading “unrealistic.” Unrealistic?! This brazenly surrealistic bit of Grand Guignol?! Why, I never expected this of Bryan Fuller! I’d better renounce my fandom.

When did appeals to realism become a trump card in pop culture criticism? And when did we agree that a certain kind of Internet commenter is the final arbiter of what is real and what is not?

I have some unverifiable theories.

1. Capitalism did it.

Today we’re living in a world where practicality is fetishized and anything dubbed impractical is anathema. You majored in engineering? You’re a hero. You majored in art history? You’re the worst, and you deserve to starve. It’s why half the guys I know say things like, “Oh, I don’t read fiction. I only read Steve Jobs biographies and The Wall Street Journal.” (They might also watch Shark Tank.) In today’s world, fiction is frivolous. Non-fiction is practical and might help you achieve financial success.

In such an environment is it any wonder that we treat works of fiction like clockwork machines and unrealistic elements as broken widgets? When someone criticizes our favorite story, we defend our enjoyment by saying the work is almost as realistic as non-fiction, and therefore it is practical and worthy. I actually met a guy once who justified his enjoyment of 24 by saying it taught him invaluable lessons about how the world really works. No wonder procedurals are so popular. They seem realistic and educational, even when they are not.

Even watching a fantasy like Game of Thrones can be framed as a practical pastime. Though few watch the show to learn to conjure a shadow baby, people do seem to take life lessons from Tywin and Littlefinger, thinking them masters of realpolitik. Act like Tywin or Littlefinger in the office and you might manipulate your way into a promotion, and you can justify your underhandedness by muttering, “In the game of raises, you win or you die.”

2. Lit snobs did it.

Maester Pycelle at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop

Although literary fiction doesn’t have to be realistic, you wouldn’t know it from the literati who decry science fiction and fantasy. We’ve all read a billion articles about how genre fiction sucks—well, unless it’s Latin American, in which case it’s Magic Realism, and the realism part makes it better.

The lit-fic world seems to be slowly changing (thanks, Michael Chabon, et. al) but I doubt my sword-and-sorcery manuscript will be welcomed in an MFA workshop any time soon. You even see this anti-genre snobbery when major outlets discuss YA literature. The dystopias and supernatural romances are raking in the cash, but only John Green’s works of realism get labeled Actual Literature.

So if you want Game of Thrones to snag some literary cred, you have to call it realistic. You say it’s not like those other fantasies with their silly zombies and wizards. Game of Thrones has realistic zombies and wizards, and they’re barely even there! Plus women get raped a lot, so it’s as miserably naturalistic as Zola’s Germinal. And miserable reality is what good art is all about.

3. Sexism did it.

Culturally, feelings and irrationality are considered feminine, while coldness and logic are masculine. Women make things up in their silly little heads, which are clouded by hormones and lady-subjectivity. Men are objective enough to see Reality. This might be why we believe more “realistic” shows (even if they are works of fantasy) are more manly than, and therefore superior to, “unrealistic” shows (even if, like soap operas, they ostensibly take place in the real world).

Since you won’t believe me unless I cite a white guy with a fancy French name, Jacques Derrida backs me up. According to his theory of phallogocentrism, in Western societies, determinateness, which is coded as masculine, is privileged over indeterminateness, which is coded as feminine.

To put it in pop culture terms, it’s kind of like the difference between hard and soft sci-fi. In hard sci-fi, scientific laws and definitions are knowable, logical, clear, and unchanging – determinate. Hard sci-fi is believed to be quite masculine. Soft sci-fi is less scientific (at least, according to our contemporary understanding of science, which might change tomorrow), and it’s more concerned with nebulous concepts like culture. In soft sci-fi there isn’t necessarily one Truth, Reality, or Logic. Definitions and distinctions might be blurred. Soft sci-fi is therefore perceived as less rigorous, girlier, and generally inferior to the hard stuff.

(Side-note: Derrida would say in Western societies everything hard is considered superior to anything soft, because boners. He’d also say the very urge to divide sci-fi into the strict binary of “hard” and “soft” is a symptom of phallologocentrism, which places high value on dichotomies like masculine/feminine, logic/emotion, and science/humanities.)

When it comes to other artistic genres, naturalism is harder, while surrealism is softer. Naturalism is premised on the notion that we can know reality well enough to mime it in our art; the setting of a naturalistic work must be determinate. Though filed in the fantasy TV section of Amazon, Game of Thrones can be considered naturalistic enough, because it is based on real history, and its few, rarely-seen fantastical elements supposedly follow strict, determinable rules. Viewers may not know what those rules are exactly, but we assume they exist. We couldn’t make Game of Thrones RPGs and board games if there weren’t hard and fast rules – a fantasy science, if you will – and these rules make the show more manly and realistic than works of soft SFF or surrealism.

(Personally, I’m not convinced the magic in GoT follows any rules. If there are rules, they seem to be changing. I’m interested to see what viewers say if and when they find out this world is softer than they imagined. Will audiences revolt, as they did at the end of LOST and Battlestar Galactica? I can’t wait to find out.)

George R.R. Martin

The trouble is, these three theories fail to answer an important question: If realism is so admired nowadays, why is no one watching the most realistic shows and movies? With its mumblecorish dialogue, understated acting, racial diversity, and subtle humor, Looking is one of the most naturalistic shows on TV. I don’t know a single other person who watches it. I don’t think I know anyone who’s even heard of it, which is sad. It’s very good.

The documentary-style Friday Night Lights? Canceled. Had to be picked up by DirecTV so it could finish its final season. Parenthood might be coming back next year, but a 1.3 rating in the key demo for its season finale ain’t great. Not when the pulpier Blacklist got a 2.7 and NCIS a 2.5.

As for movies, well, I don’t need to tell you. How many people saw Before Midnight, and how many people saw Captain America? We’re still judging superhero movies based on their realism (a friend recently raved about The Winter Soldier by calling it “barely fantastical—it could happen in real life!”) but when it comes to watching actually-realistic movies about real people dealing with real conflicts in the real world, audiences are nowhere to be found.

So here’s what I want.

I want the Internet to stop pretending it actually cares about realism as a genre. You like dragons and superheroes and pulp. It’s okay. It’s awesome. Own it.

I want people to stop acting like realism is the most important criterion to use when judging pop culture. Character consistency matters, too. Emotions matter. Artistry matters.

I want people to stop applying the rules of naturalism to stories that aren’t trying to be naturalistic. I hate to say you’re watching wrong, but you’re watching wrong.

Most importantly, I want people to stop justifying sexism, racism, and general misanthropy with appeals to realism. We never said we want to see fewer rapes in Game of Thrones because they’re unrealistic, so arguments on these grounds are illogical. And the next time you start to shut a conversation down by saying, “It’s realistic” or “It’s not realistic,” maybe take a second to ask yourself, “So the f*** what?”