[Enjoy this guest post by Phil Edwards! —Ed.]

The romantic comedy pulls off an incredible trick: people love it and hate it for the same reason. Predictability makes the rom com divisive. For some movies you quote lines, but for rom coms you quote cliches. The meet-cute in the beginning, the misunderstood phone call at the end of the second act, and the chase at the end aren’t so much plot elements as they are predestined conclusions. Yet even the rom com, the most predictable of genres, has changed dramatically over the past thirty years. That’s because we’ve changed dramatically, too.

We know because we crunched the numbers. We took the top 100 rom coms from 1980 to present (by U.S. gross) and compiled data about the characters’ jobs and salaries. Like romance itself, our study is imperfect and has some lovably neurotic caveats (we encourage you to read our methodology or look at the spreadsheet to learn what they are). Still, we think that the salaries in rom coms reveal how romantic escapism has changed through the decades.

Our graph gestures at what that change is. As the decades progress, male and female characters’ salaries have clustered closer together, and significantly more women have started out-earning their male counterparts. Over the years, our heroes and heroines have found their way to a more equal workforce.

Both male and female jobs have changed. The data show that today’s male protagonists are less likely to be billionaire playboy heroes, captains of industry, or heirs. In turn, the ladies are more likely to be entrepreneurs, businesspeople in their own right, and professionals instead of the waitresses and secretaries that dominated the earlier years of our data. Part of this is a change in society—if rom coms didn’t acknowledge a recognizable shift in the labor force, they’d appear as outdated as if the characters still used rotary phones. The romantic comedy has to have real world texture to make it relatable.

But romantic comedies aren’t just reflections of reality—they’re reflections of our escapist desires. The change in the class relationship between male and female characters isn’t only tied to Bureau of Labor Statistics reports. It’s tied to the fantasies of the studio executives that got the movies made and the audiences that made them popular. Modern studios and audiences have chosen stories with a different dynamic because those stories reflect the modern romance they dream about.

In older romantic comedies, the man made more than the woman and that class relationship was reflected in the subtext of the film. When audiences watched Pretty Woman, they were charmed rather than offended. Vivian Ward gained stability and security through love and Edward Lewis got affection and a relationship apart from work. Many of the rom coms in the 80s and 90s mirrored that arc, and it’s made explicit in the data’s differences between male and female salaries. In general, the man saves the woman through security and the woman saves the man through emotion.

But that began to change in the 2000s. Suddenly, the relationships become more economically equal, and that corresponds with a shift in how the characters love each other. Instead of looking for a savior, each character is looking for a partner. When the women in Fever Pitch, The Proposal, and No Strings Attached search for love, they don’t want someone to rescue them. They need a partner that can breathe life back into their work-driven existence. And the men no longer need to expose themselves to sentimentality—they’re already gushing and desperate for a loving partner, not a damsel in distress. The equality in their salaries is a match for the equal partnership they seek.

Are there exceptions? Of course. Some of the most notable romantic comedies buck the trend, and that’s a great reason to collect a large sample. In general, however, characters’ salaries and dynamics have demonstrably changed. Modern audiences have different things to escape from. We used to escape from uncertainty. Now we escape from monotony. A relationship is less of a rescue effort and more of a team effort. Love is sought as an intoxicant rather than as a salve.

Is that a good or bad change? Was either type of rom com sexist? Does either reflect the values we want in the movies? What’s more romantically desirable or emotionally true? All that’s beyond the scope of this article and the data we’ve collected. Still, we feel comfortable hazarding at least one guess based on the numbers. Rom coms may be predictable, and we may always have that last minute chase to the airport. But despite the cliches, rom coms will keep giving us an escape because even the most predictable genre is willing to change.

Phil Edwards’ writes pop culture trivia like this for Trivia Happy. If restricted to the most traditional rom coms, Music & Lyrics might top his list, but with a little more latitude he’d pick Groundhog Day or Defending Your Life.

I think it’s an interesting theory but as you said, it would benefit from a larger sample of films before major conclusions can be drawn. As the world’s foremost expert in romantic comedies (podcast joke), I have serious questions about the validity of a lot of the statements you make in this piece. I don’t think you can talk about romantic comedies in a piece like this without acknowledging the years and years of romantic comedies (even just in film) that preceded the few decades you are scrutinizing. Not only would expanding the sample provide a clearer picture of a societal shift (if there is one) but I think it’s actual vital for a discussion of romantic comedies. A lot of those conventions were established in the early romantic comedies of the 1930s and reworked in the romantic comedies of the 1950s and 1960s. When newer films adopt those same tropes and ideas they carry over the same gender, class, etc. dynamics or change certain elements in reaction to those films.

For instance, you can’t talk about You’ve Got Mail without talking about The Shop Around the Corner and In the Good Old Summertime. As a remake it carries over most of the same plot elements but it introduces new technology and chooses to change the occupation of the characters in a way that exaggerates the power imbalance, changes their respective salaries, and alters their dynamic as the original film and sequel were more workplace comedies.

I -love- In the Good Old Summertime. And I think you’ve hit the nail on the head what I disliked about You’ve Got Mail. It had been nagging at me, something just wasn’t sitting right, and I think that’s basically it. Instead of two co-workers snarking at each other, there was Big Bad Box Business basically ripping Quirky Family Independent Store apart. She loses her job. She loses something that meant the world to her, and I can’t find it in my heart to cheer for them at the end.

ItGOS, she gets her job through determination and pluck, and excels. He was complacent, and he was forced to step up his own game. They made each other better.

In YGM, it was backbiting and belittlement and snideness, and the playing field was decidedly unequal.

side note: I frikkin’ LOVE Steve Zahn in YGM. “He’s the rooftop killer!”

Just want to throw in my ditto on loving In The Good Old Summertime. Also want to toss into the conversation Pillow Talk with Rock Hudson and Doris Day as a middle part of the Shop Around the Corner lineage between Summertime and You’ve Got Mail. My memory of the film was that this was a case where the woman was notably less economically powerful than the man but a glance at Wikipedia tells me that she is a successful interior decorator so I guess not. I think there is one Rock Hudson/Doris Day one where he is a millionaire and she a secretary or something, so I think I was confusing them in my mind.

A little googling reveals that the “millionaire/secretary” movie I was thinking of wasn’t a Rock Hudson/Doris Day movie (there are only two more of those and in one they are married an in the other they are career rivals), but rather of A Touch of Mink with Doris Day and Cary Grant, which starts with him splashing mud on her suit as she walks to a job interview as he drives his Rolls Royce. I at least got the millionaire part right.

I’m so happy to discover some other old movie fans on OTI! I think it’s important to bring these films into the conversation because gender and occupation can play in the romantic comedy genre. I don’t have the numbers to back me up but I’d say there was a lot more of a class distinction in earlier films with one character in the pairing who ‘came from money.’ And throughout the generations you have a lot of films displaying anxiety with women entering the workforce and specifically job sectors dominated by men. I don’t think it’s large enough of a shift to really matter but my sense of things is that the rise of “slacker” male characters and the aggressive backlash against career-driven women (e.g. What Happens in Vegas) might account for more of the imbalance in more recent films.

Of course, I still feel like it’s hard to find a pattern of dramatic shifts because films are intended to cater to different fantasies and there is no one universal female fantasy.

I has a bunch of thoughts on these things, so I made a forum post. Hope to see some folks there!

Oh, and PotatoKnight is me. I should really make a new registered login.

PotatoKnight is Connor Moran, rather. Sorry to clutter this with this nonsense but I can’t delete or edit and don’t want to sockpuppet accidentally.

Just want to start out by saying that I love that you undertook this project and that this is one kind of content I’d love to see more of on OTI–the quantitative analysis is always fun and I like to see OTI looking at things like romantic comedies. The data were super fun to play with, and I love that you made this corpus.

Unfortunately, I’m not sure that the data presented support the conclusions drawn.

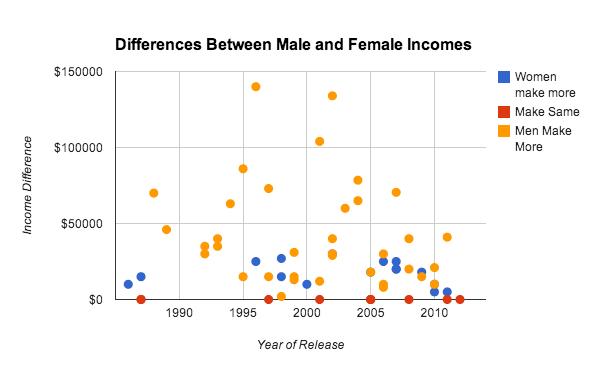

I had a little trouble drawing any information from the graph presented, so I pulled down the data from the spreadsheet and made a few scatterplots of my own. I took out any points where we don’t have salary data for either the woman or the man, then calculated for each film the difference between the woman’s salary and the man’s. If the woman’s salary is higher, the number is positive. If the man’s salary is higher, the number is negative. I made a scatterplot using the date of film’s release as the Y axis.

Here is my result.

Immediately, I notice a problem. Because there are some very outsize salary differences going each way, the scale of the plot is such that any trend in the less dramatic salary differences vanishes. So just for visual purposes, I “cropped” the data, making any salary difference more than $1 million into $1 million.

Here is that chart.

Just eyeballing this chart, I don’t really see much of a trend at all. The majority of films cluster in the center with no hugely noticeable salary difference. There is another collection of films with a large salary advantage to the man. These seem largely consistent over time. And there are a few films toward the end of the chart with a big salary advantage to the woman. This seems to be the basis of the thesis.

But this kind of eyeballing for trends is notoriously unreliable. So I went back to my unaltered data and threw a trendline on there. Now, if we are really seeing a trend toward women making more money compared to their paramours, we should see an upward line.

Here’s that chart.

(note that this chart uses all of the data to make the regression line but doesn’t show the really big salary differences because I zoomed in to show the line)

The line goes down, suggesting that, if there is any trend, it is toward men making more than women, not less.

A regression analysis on the same data suggests that this “trendline” is a phantom. There is basically no relationship between time and the salary difference.

You can see all the charts together in one imgur album here

OK, but that’s focusing on how big the difference in salary is. But what about just the mere fact of the difference? Can we support a conclusion that it is more likely today that a female lead in a romantic comedy will make more than a male lead?

I decided on a simple way to test this qualitative information. I would figure out the median date for movies on the chart and see how many women before that date made more than men and then looked at how many women after that year made more than men. The median date was August 12, 2002 (between Sweet Home Alabama and Mr. Deeds).

Before August 12, 2002: 14 women made more than men, 30 men made more than women, and 4 had the same salaries.

After August 12, 2002: 14 women made more than men, 28 men made more than women, and 6 had the same salaries.

Qualitatively and quantitatively, it appears that over the time period we’re looking at, there is no discernible trend in the relative economic power of the protagonists of romantic comedies.

Hey, thanks so much for doing this. Your work and graphs are all awesome. This is why this site is so cool.

In response to Cat, I’d say that while tropes in earlier rom coms are interesting, I was more interested in the success of the movies than in cinematic tropes, since those tropes are subjective and could be the result of just a handful of individuals (like Nora Ephron) and not a reflection an entire culture.

To Connor, this is great—exactly why it’s so awesome to have people work with the data. By the way, I’m so paranoid about making mistakes in this reply that it’s all the more impressive how thorough your comment was.

I’d respond in this way—I had a much sharper crop than you did. In the graph included, I believe I removed all the clunkers (the no data entries) and also trimmed the top and bottom twenty percent (I say believe because I may have gotten rid of one or two extra). You can see that in the graph I limited the salaries to 150k instead of a million.

I also think that it’s important to measure by smaller units—ie, decades—rather than just a pre or post 2002 measurement. Your median method is definitely sound for the data, but I don’t think it gives short shrift to the difference between, say, 1999 and 1980.

Of course, my method obviously “massages” the data in a way that supports my conclusion. However, I didn’t go into it with a preconceived notion of the outcome. My argument (which it’s equally valid to accept or reject) is that the way I “massaged” the data reflects the aim of the study: how real, relatively normal jobs are portrayed in rom coms. I think removing all the outliers like movie stars, bankers, and princes was important to get to the meat of media people and bakers. These are the cliches that best inform how we think of romantic comedies, so I wanted the data to show them (as well as any graphs).

So that’s my attempt at justifying how it’s framed, but I should emphasize that I can completely understand the “no conclusion” side of the argument and think it’s awesome you messed with the info. However, I was pretty intentional in the way the data was represented and do still believe it was appropriate for the question I wanted to answer. Statistically and anecdotally, I do still support the conclusion in the article. But if it’s too much “data massaging” for anyone, I can understand (massaging may be too R-rated for this PG-13 genre anyway).

Can you elaborate a little more on the bottom and top 20% you cropped? Bottom and top 20% of salaries overall? Or bottom and top 20% of salary differences? I’d like to dig in a bit more to see if we can make some common conclusions, but I’d like to compare apples to apples.

Cat, I think we just have different goals. But that’s fine! I explain a bit about mine in the linked methodology.

Connor, so the graph is limited to 150k differences and below. Obviously, the graph is simply representing a portion of the data. It ends up showing 64 differences.

How did I arrive at that number? Well, I was interested in seeing the differences between people who had real jobs (ie, they weren’t princes or movie stars). Sorry, I’m sure I sound like a broken record here.

I’m afraid that no matter how I’ve cropped and sliced up the numbers, I haven’t been able to come up with any formulation that mathematically supports the conclusion that there is any relationship between the passage of time and salary equity in films. There are movies from recent years where the woman has made more money than the man–but also movies from the 80s where that is the case. There are movies from the 80s where the man makes a lot more than the woman–but also moves from the last few years where that is the case. The relative frequency of these types of films appears static over the years considered here.

I would have liked to have found a relationship (we’re talking about romance, after all!), but it just doesn’t seem to be there.

Well, fortunately everybody can draw their own conclusions!

“In response to Cat, I’d say that while tropes in earlier rom coms are interesting, I was more interested in the success of the movies than in cinematic tropes, since those tropes are subjective and could be the result of just a handful of individuals (like Nora Ephron) and not a reflection an entire culture.”

Right, but I think even films that aren’t remakes are building off a similar framework that can’t be ignored in this kind of analysis. How To Lose a Guy in 10 Days and What Women Want are good examples of films that owe a lot to 50’s and 60’s romantic comedies. But while What Women Want keeps a basic workplace comedy structure, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days kind of contorts itself with a bet to have the male character work in advertising while the female character is a writer for a magazine. I think you’d gain something by expanding this analysis to movies like Sex and the Single Girl and Lover Come Back.