In the new videogame The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds for the Nintendo 3DS, childhood and nostalgia are not only a marketing tactic but also a powerful thematic presence that strongly informs the game’s meaning and cultural significance.

From a superficial first glance, A Link Between Worlds might seem like little more than a slightly beefed-up port of its predecessor, The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, the 1992 game originally released for the Super Nintendo Entertainment system. But while Nintendo has rereleased earlier 2D games with newly enhanced 3D graphics to give a nostalgic experience of old games using cutting-edge technology, A Link Between Worlds is absolutely an original and whole work that significantly builds upon A Link to the Past rather than merely repackages it. In fact, the many deliberate parallels, call-backs and references to A Link to the Past that populate the universe of A Link Between Worlds serve to comment on the evolving role of videogames in our lives: it hearkens back to our own childhood by placing the new game in the same setting as the old one, while using the recurring theme of childhood in general and lost children in particular, in combination with a gameplay mechanic that requires switching back and forth between 2D and 3D to stress the similarities and differences between how we played games back then with how we play them today.

First of all, the game’s titles deserve some attention. A Link to the Past is not actually about time travel, although the title suggests it (that would the 1998 Ocarina of Time for Nintendo 64). The “link to the past” refers only to the fact that the game takes place chronologically earlier than the original NES game, The Legend of Zelda. Link to the Past was the third game in the Zelda series, and followed the largely unsuccessful The Adventure of Link, which was the proper sequel to the original. The plot of the game would have dictated that the correct title for that game should have been A Link Between Worlds, as it revolved around the protagonist, Link, travelling between the “Light World” and “Dark World” to prevent the Demon King Ganon from launching an invasion of the former from the latter. The actual game A Link Between Worlds has a similar plot, with Link again having to travel from his homeland of Hyrule to its parallel universe of Lorule, but from a more meta perspective it really ought to have been called A Link to the Past – it was very deliberately modelled after the 1992 game visually and in terms of story and mechanics, and for someone who played its predecessor in childhood like so many of us did, it really does serve as “a link to the past,” throwing us back in time through a portal of nostalgia. The overworld map in the new game is nearly identical to that of the old one, and the player’s muscle memory easily recalls the way around and the little secrets that populate the overworld of Hyrule.

Overworld maps from A Link to the Past (left) and A Link Between Worlds (right)

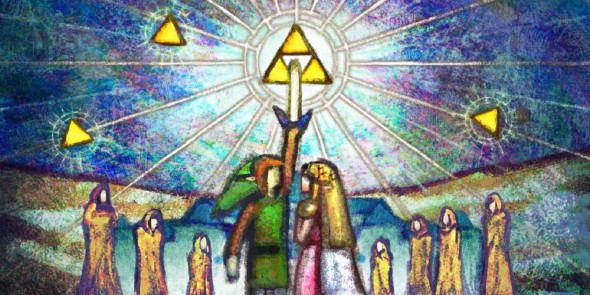

The two games do take place in the same timeline and the same world, though centuries apart. We learn (by viewing a series of paintings in Hyrule Castle early in the game) that the events of A Link to the Past have been enshrined in history, with a legendary hero rescuing the Seven Sages and the Princess of Hyrule and saving the world from the Demon King Ganon – tasks that we remember very well as a player, since we were the one who accomplished them all that time ago. It’s well-established that the history of Hyrule is cyclical, with a new Princess Zelda and new hero Link being reborn time and again and playing out their destiny to defeat the forces of evil and reinstate the magical Triforce to its rightful place in creation.

Link himself is only a child, and as the player returns to childhood through this new and yet intimately familiar game, there is an essential gameplay element that also deliberately hearkens back to what were then the practical limitations of the medium; the normally three-dimensional Link gains the ability to become a two-dimensional, impressionist-style painting of himself. This allows him to walk along walls, traversing chasms where there is no bridge and entering otherwise inaccessible areas through narrow gaps. It is also the secret to travelling between worlds – while in A Link to the Past, traversing the dimensions was accomplished mainly through the use of square-shaped portals hidden strategically across the map, in A Link Between Worlds, Link achieves the same effect by moving through cracks that have appeared everywhere since the barrier between Hyrule and Lorule was ruptured; the cracks are so thin that a regular person could never fit through one, but a two-dimensional Link can slide right in easily.

Get in there.

The crudely beautiful two-dimensional Link reminds us of the less technologically sophisticated games of the past, in which a more iconic and less representational art style was a matter of hardware limitations as opposed to being an artistic choice on the part of the game’s creators. In fact, this Link most obviously resembles the side-scrolling protagonist of the mostly unsuccessful Zelda 2: The Adventure of Link. While A Link to the Past returned to the tried-and-true top-down viewpoint of the original Legend of Zelda, advances in graphics technology does not necessarily equate to a better gameplay experience, and this particular mechanic in A Link Between Worlds, mastery of which is absolutely essential to progressing in the game, directly evokes that message. The link between worlds in this game is also our link to the past; the primarily three-dimensional (or, technically, stereoscopic) game also uses 2D in what is now a deliberate stylistic decision to arouse a sense of nostalgia in the player above and beyond the game’s setting. This way, the nostalgia is embedded in the game’s narrative and gameplay, and it reinforces nostalgia and childhood as a literary theme rather than appealing to nostalgia for reasons of pure marketing.

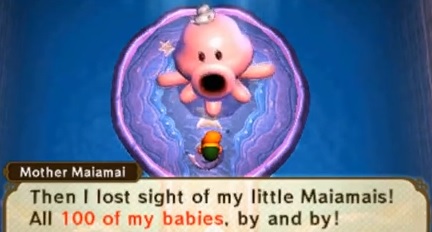

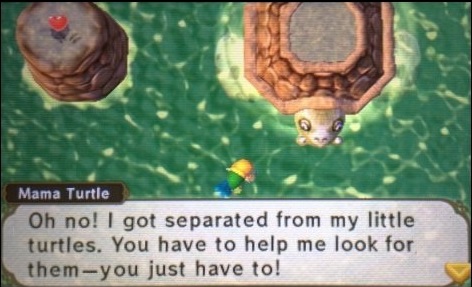

At the same time, children and childhood is a major theme and narrative engine in the game as well. Aside from the fact that Link is repeatedly referred to (and dismissed as) a child, there are no fewer than four subquests or plotlines in the game that revolve around returning lost children to their parents. At various points, Link is charged with finding: his friend Gulley, who has disappeared and whose parents are worried sick about him; the young witch Irene, who has been snatched away from her potion-brewing grandmother; three baby turtles who have been misplaced by their mother, and one hundred baby creatures called “maiamais,” whose mother also lost them throughout the world and offers rewards to Link for returning them.

The “free-range children” parenting method backfires in the Land of Hyrule.

Now, “find and return” quests are certainly nothing unusual in videogames like this, and there are many more of them in A Link Between Worlds than just these – but the repeated theme of missing children is more than a convenient excuse to make the player run all over the world looking under bushes and atop mountains. It’s that too, but it’s also a way to reinforce the sense of it being “a dangerous world out there” and simultaneously, and more significantly, engage the player at the level of child and adult simultaneously. In a similar way that the shifting between two and three dimensions serves the gameplay while creating a nostalgia portal for players who remember the earlier game, this form of quest functions by causing sense memories of childhood to re-emerge and become superimposed on the context of the adult gamer. Link himself, whom the player controls, proves that a child can also be a hero (a theme that would have resonated with a young player on the Super Nintendo just as well as it would with a young player today), but he also needs to rescue other children on behalf of adults who are incapable of doing it themselves.

Of course it won’t be only adults who play this game, and the younger players won’t be struck with the sense of nostalgia for A Link to the Past that is part of the appeal of A Link Between Worlds, but many of the game’s players will be adults, and a good proportion of those will be parents themselves today, for whom losing their children would likely be a nightmare come true. We identify both with the terrified parents and with the missing children as the player/Link is poised at the point of overlap between childhood and adulthood, between acting and being acted upon, between the present and the remembered-past and the past and the imagined-future. The effect is directly analogous to the way that the 3DS creates an experience of seeing in three dimensions by creating overlapping similar but slightly different images that are seen in subtly divergent ways by each eye to converge in the mind as a single, unified image with apparent depth, though appearing on a flat screen. Youth/childhood and its privileged position in our psyche is part of the appeal of this game’s design, but the yearning for an era gone by – and the possibility of recapturing it – is also on the surface of what A Link Between Worlds is trying to convey to us.

Finally, the sense of nostalgia and a yearning for a return to the magical feelings of the past is also an explicit plot element in A Link Between Worlds, beyond being a reason that adults may want to play the game.

There are bunch of major spoilers after this point, just to warn you.

This used to be such a nice place.

The parallel universe of Lorule once, like Hyrule, had its own version of the Triforce – a magical relic that was a gift from the gods that provides nourishing energy to the world and can grant a wish to anyone who possesses all three of its pieces. The Triforce is somewhat of a double-edged sword, with the majority of the Legend of Zelda series centring on the evil Ganon’s attempts to obtain the Triforce for himself, with Link fighting to prevent the Demon King from using it to remake the world in his own image. Given all the trouble it causes, it’s understandable that the ancients of Lorule decided they had to do something to prevent the wars and disputes that constantly arose from people trying to get the Triforce for themselves to make their wishes come true; they destroyed the Triforce in the hopes of restoring peace to the kingdom, but discovered that without the Triforce’s life-giving energy, Lorule began to decay and crumble, falling into darkness.

Ultimately, we learn that the entire course of events in the game has been orchestrated so that Lorule can steal Hyrule’s Triforce and return to the glory of its past. The overlying motifs of childhood and adulthood, and of moving back and forth between two-dimensionality and three-dimensionality and between a bright and magical world and a dark and monstrous one parallel and interweave with each other extensively and quite intentionally.

The driving narrative force in A Link Between Worlds as well as the game itself both hinge on the attempt to recapture a past era that was full of light and magic but which has, because of the loss of an object glowing with wish-granting potential, has devolved into darkness and drudgery. Just as the quest for a new Triforce to replace the one that was destroyed by the high-minded hope of moving past discord, A Link Between Worlds, through its retro style and nostalgic design, offers the adult player a genuine step back in time to a childhood illuminated by games and mysteries – a link across time that is, we happily discover, as close as the next coffee break or crack in the wall.

You tie Lorule’s yearning for the lost Triforce to an adult’s nostalgic yearning for the lost wish-granting power of childhood. That’s really interesting, in light of the story you describe where Lorule is actively trying to steal that light from Hyrule–understandable under the circumstances but fairly classed as evil. Would you say that this nostalgic video game has an embedded critique of nostalgia? Or does that plot just serve to evoke the tragic loss feelings we associate with nostalgia?