[Enjoy this guest post from Connor Moran! – Ed.]

1993 was a weird year to be a spy film. For 30 years, the genre was dominated by two intertwined influences: the Cold War and James Bond. In 1993, the Cold War was over and James Bond appeared to have driven his Aston-Martin into the sunset. In the 27 years leading up to 1989’s License to Kill, there had been on average a Bond film every year and a half. By 1993 there had been an unprecedented 4 year gap.

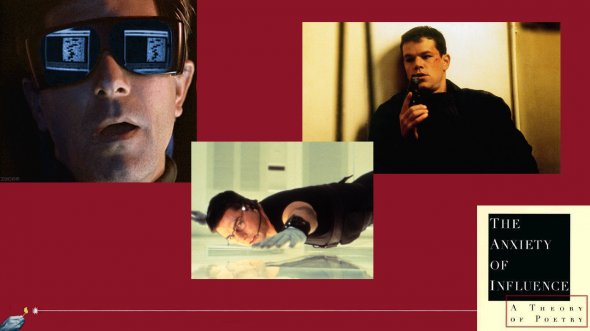

Into this gap stepped a group of unlikely spy film protagonists. These guys:

Even with the Bond franchise absent, it still cast its gun-wielding silhouette over the genre. Every cable network wants to be with him, every spy franchise wants to be him. What is a new spy film to do when approaching the towering influence of something like James Bond?

Harold Bloom has the answer. Harold Bloom is a well-known–if controversial and not very stylish–literary critic. His breakout hit, as breakout hits are evaluated in the world of literary criticism, is a 1973 book called The Anxiety of Influence. In the book, he examines the experience of the young poet (the “ephebe”) encountering a great poet of the past. His thesis is that the ephebe yearns for immortality in the mode of the past master. In order to fulfil that yearning, however, the ephebe must make original work. This contradiction–to be influenced by the master yet yearn for originality–produces anxiety, which a great poet resolves using a number of techniques Bloom identifies as “revisionary ratios.”

Just in case you were wondering.

Sneakers’s Bond-anxiety is on display from the beginning as it invokes that franchise comically in the very first scene–in a flashback when Robert Redford’s character Marty goes to get food his friend Cosmo asks for “pepperoni pizza–shaken, not stirred.”

When we move to the present, we meet the grown up Marty–and see the film’s Bond-beating game plan. It will empty itself of Bond by creating an anti-Bond. Where Bond is a lone heroic figure with little or no support, Marty is one member of a team. Where Bond is on Her Majesty’s secret service, Marty never works for the government as a point of principle until apparent NSA agents blackmail him (spoiler: and actually not even then). Where Bond drives a shiny Aston-Martin, Marty drives a rusty, creaking VW convertible.

A cool, creaking, rusty VW, but still.

The absence of Bond is one powerful negative space in the film. The other is the Cold War. Spying is still going on, but without the enemy the focus of that espionage is unclear. The movie suggests that when the enemy is gone there is nobody to spy on but yourself. The film several times makes it clear that the NSA cannot legally perform domestic surveillance. Yet it becomes clear by the end of the film that the black box everyone wants was A) ordered built by the NSA and B) useful only for domestic surveillance.

Yes, this movie was made 20 years ago.

Like Sneakers, Mission: Impossible comes to the conclusion that the only real enemy is ourselves. The first mission is nothing more than an elaborate act to find out who is betraying the agency. The villain comes from within. We never get the sense that the IMF has any particular outside enemies. Even Vanessa Redgrave’s charming arms dealer–the only antagonistic outside force depicted–is helpful to Hunt for most of the film and appears to be helpful to the IMF at the end.

Geopolitical situation aside, M: I follows Sneakers in the ways Sneakers divorces itself from Bond. While protagonist Ethan Hunt is a competent spy he feels more like a normal guy pushed by extraordinary circumstances than like Bond’s infinite suave (this would change in subsequent installments). Like Marty, he operates in a team. When his team is gone and he needs to accomplish a task, his first act is to assemble a new team. While Hunt is a government agent at the start of the film, the IMF itself is his primary antagonist for most of the film.

But since M: I wants to taste immortality, it couldn’t simply follow Sneakers on its path away from Bond. M: I had to break from its predecessor. And it did so with the revisionary ratio Bloom calls the “clinamen” or swerve. With the clinamen, the ephebe drives toward the influence but at a crucial point swerves away like the loser in a literary game of chicken.

Consider the following: Marty’s team needs a computer device out of a room. The room is protected by a keycard and voiceprint ID held by a schlubby guy; a heat sensor; and a motion detector. The team sends a sexy lady to distract the schlubby guy, messes with the temperature, drops Marty in from a ceiling vent, and has him walk real slow to beat the motion detector.

Especially sexy if you’re into space presidents.

Consider the following: Hunt’s team needs a computer file out of a room. The room is protected by a keycard and voiceprint ID held by a schlubby guy; a heat sensor; a sound detector; and a pressure-sensitive floor. The team sends a sexy lady to distract the schlubby guy, messes with the temperature, drops Hunt in from a ceiling vent and has him talk real quiet to beat the sound detector.

Oh, yeah, and here’s the swerve: he has to dangle from the ceiling.

At the crucial point, Mission: Impossible swerved away from the influence by adding just one more complication. And there, for that moment, it achieved the goal of immortality. The ceiling-dangle became an icon of spy film, etched into the genre as much as any scene from Bond.

In Bloom’s formulation, the vast majority of poets do not have the capacity to overcome influence and achieve greatness. Likewise, not every film that confronted the influence of Bond was able to leverage the revisionary ratios. Mission: Impossible II, unlike its predecessor, adopts the Bond form of largely solo hero working for the government. The result is a middling Bond film with John Woo visual flair rather than a recognizable Mission: Impossible sequel. xXx adopts a revisionary technique Harold Bloom never anticipates: machine-gunning a caricature of the master. Points for moxie, but sadly the film’s apparent premise “James Bond except cool” fails almost as a matter of formal logic.

But a film can be more like Bond than Sneakers and M:I yet still avoid the trap. The revisionary ratio that becomes the greatest triumph over the anxiety of influence is the apophredes, a Greek term that means “the return of the dead.” This occurs when the ephebe confronts the influence and, rather than be swallowed, masters it. When successful, this produces the paradoxical sense that the works of the earlier master were influenced by the ephebe rather than the other way around. One spy film manages to attain this status vis a vis James Bond: The Bourne Identity.

Apophredes.

The Bourne Identity descends also from Sneakers and M: I. Its plot is highly reminiscent of M: I–a rogue agent is hunted by his own former boss. The film is as ambivalent about espionage as the other films, albeit in a different way. In 2002, the sense that US espionage was pointless had dissipated. It was replaced by a sense that US espionage might be the kind of meddling in foreign affairs that has unpredictable and deadly consequences for the homeland.

Bourne himself is quite different from Marty and Hunt. The Bourne Identity doesn’t run away from the core Bond premise of a solo, heroic, spectacularly competent spy protagonist. It doesn’t even run away from the initials J. B. Yet unlike Mission: Impossible II and xXx, it doesn’t mindlessly ape the Bond model. Bourne’s violence is more personal than Bond’s technology and explosions. He gets his hands dirty, and rather than gadgetry he uses any and every weapon in the vicinity. When Jason Bourne kills you with a pen, it isn’t because the pen is really some gadget.

And he doesn’t quip that it’s mightier than the sword.

More fundamentally, the film wrestles directly with what it means to be a superspy. Bourne–who has all the skills but no memory–lays out for the audience exactly what it means to live inside the head of an impossible badass. And it doesn’t seem like a cozy place.

Also in 2002, the Bond franchise took another uncharacteristic break after the four Pierce Brosnan films. And when it came back in 2006, it didn’t look like itself. Daniel Craig is still cool, but beneath the surface it is clear he is troubled the way Bourne is troubled. It was obvious that Bond was influenced by Bourne. Bourne achieved apophredes–he conquered the anxiety of influence and made Bond the follower.

[Connor Moran writes mostly for the narrow audience of the United States Tax Court. His montage celebrating hacking in film “Haxploitation People” could really use more than 270 views.]