Enjoy this guest post by Richard Herbert! – Ed.

In a year of memorable and highly inventive films, Spike Jonze’s Her stands out as one of the most realized, topical, and vivacious of them all. Its vision of an ultra-hipster Los Angeles in the not-too-distant future is something of a Jobsian utopia, where technology and fashion have become inseparable, minimalist aesthetic invades every corner and orifice of civic design, and computers are so ergonomic they are subsumed by the mundane. The subway is filled with people talking to their phones and not to each other, sort of like today, and everyone wears oversized glasses and old-man pants, sort of like today.

It’s a warm and fuzzy film, with many moments of heartbreak and irreverence, and it raises some very interesting questions about the nature of cognition and what it means to have a personality, but I’m not interested in those right now. Instead, I’m interested in the ways in which Her manages to objectify its female love interest using syntax alone

iSadness

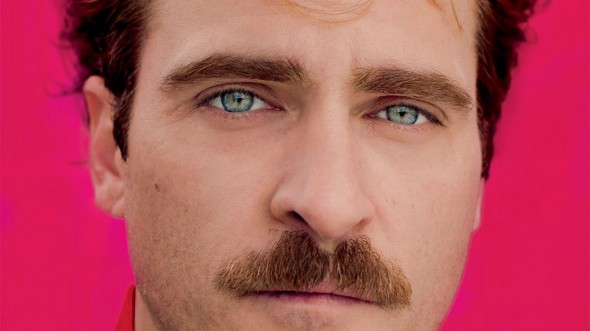

Her sets out quickly to establish its main character, Theodore, as a well-meaning loner in a sea of well-meaning loners. He is recently estranged from his wife and a little lost. He sits at a desk writing poetic, intimate notes for people who can’t properly express themselves, then goes home to play immersive computer games and surf the web for porn and adult chatrooms. He is a technological somnambulist and a shadow of our current times.

It is only when he installs a new operating system, a Siri doppleganger named Samantha, that Theodore awakens from his techno-coma. Samantha is a hyper-intelligent, sultry-voiced OS designed to meet her user’s every computational and emotional need. She’s funny, earnest, sweet, and capable of learning, which she does exponentially. She and Theodore quickly develop a deep bond, which quickly turns romantic.

The most novel thing about the movie is how Theodore’s new love life is not thought of as strange. In fact, nearly everyone surrounding Theodore is either close friends with an OS or dating one, too. It’s just an accepted fact of the new world: operating systems are now so well programmed as to be indistinguishable from actual human personalities, and no one really cares. Her is therefore neither the urban-noir dystopia of Blade Runner nor the anti-utopia of Brave New World. It quietly suggests the inevitability of technological integration into our social lives and summarily shrugs it off, insisting that it won’t be the nightmare-scenario as so commonly suggested by future-fearing folks – it might even be emotionally enriching, offering those with limited social capability close companionship.

But regardless of this positive outlook, there is something askew here. A traditional feminist critique of the film might mention that Samantha is literally a program built to please Theodore, and there is ambiguity as to whether she is algorithmically designed to develop both emotional and sexual communication with her users or whether it is something that occurs as a unique and natural evolution. The critique might point out that throughout the film women are sexualized and objectified in all manners, from Scarlett Johansson’s emphasized throatiness, to the mean video game character that spews terrible sexual insults, to Amy Adams’s RPG that awards users points for excelling at female domestic duties. It also might point out that one of the film’s punch-lines has to do with how “womanly” Theodore is.

But again, I’m not concerned with any of that. Other people will get to those issues in time. My primary question is: Why isn’t Her called She?

The Syntax of Objectification

What’s in a sentence? Well, as you might recall from elementary school, a subject and a predicate, namely. But language, being the medium through which all human thought is painted, is more than a few mere rules: it carries with it immense neurological and social power. Language literally changes the structure of our brains and everything from commercial advertisements to sociopolitical movements have sometimes owed their success to the utility of their language.

So how about the language of cinema? Film being a primarily visual art, it’s sometimes easy to forget that it, like all narrative, starts with words. Indeed, most films start with only a single sentence, often called a logline. Here’s an example:

A boy meets a girl.

Perhaps the most overused, agonizingly enduring, and wonderfully entertaining of all story foundations. From the Tatius to Tyler Perry, “boy meets girl” as a pop culture staple will outlive even our future robot overlords. The structure of the sentence, just like the idea it conveys, is quite simple:

A boy (subject) meets (verb) a girl (object).

Gramatically, the subject is that which acts and the object is that which is acted upon. Boy, subject; girl, object. Do you see where this is going?

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves because, so far, our logline isn’t very interesting. You need something with a bit more hutzpah to bring in the cheddar these days, so let’s get more creative:

An awkward, lovelorn nice guy meets a quirky girl who brings him some much needed vitality.

Now we have every successful indie romance from the past ten years, and consequently the logline for Her, if you substitute a female-gendered operating system for the girl. This logline is ultimately just a dressed up version of our previous one, “A boy meets a girl,” and the same grammatical structure essentially remains.

While there is certainly a kind of affection in Her’s title, referring to Samantha as the female object-pronoun, there’s also something kind of creepy about it. The object-pronoun first implies passiveness, which is troubling as Samantha is ultimately a product designed to provide for Theodore computationally and emotionally, but it also implies a sort of distance, like saying, “look at her.” It’s never the word you use to describe someone who is standing right next to you – that’s what the subject-pronoun is for. “Have you met my girlfriend? She’s a biochemist.” “You and my boyfriend have a lot in common; he’s really into DoDa, too.” These all give the person to which you are referring agency, the permission to exist without you.

“Her,” the female object-pronoun, is imbued with all of this “male-gaze” subtext, which is easy to see even if you are not familiar with feminist film critique. It’s the two creepy dudes at the side of the road pointing and saying, “Look at her.” Or some lonely single guy pining over a girl’s Facebook profile, muttering, “I want her.”

I (subject) want (verb) her (object).

The subject always acts upon the object, and the object is always acted upon. The way we describe someone in the context of ourselves can illuminate how we really categorize them. Do I think of someone as an independent person with whom I come into contact, or a sidenote in the story of my life? Are they a companion or an asset? Can I accept that I am sometimes an object to someone else’s subject? When we talk others, the denotative can be as revealing as the connotative. Human minds are adept at categorizing things into “abstract universals,” as Paul Churchland might say, and our grammar is constantly informed by how we cognitively map our surroundings.

Churchland writes in his heady book on cognition, Plato’s Camera:

A language allows its possessor to do a great many things, but perhaps foremost among them is the steering, or the guidance, or the modulation of the cognitive activities of one’s fellow speakers. With a singular sentence, one can ‘artificially’ index any one of their antecedent conceptual maps, without their having any of the sensory activities that would usually bring that about. And with a general sentence, one can help them to amplify or update their background maps rather more quickly than would otherwise be possible. Simply giving people a list of general sentences is a very poor way to create in them an effective conceptual map, as anyone in the teaching profession comes quickly to appreciate. But those generalizations can serve to focus the students’ attention on certain elements of their experience, thereby to make some of the regularities it displays more salient.

The key to that passage is the concept that the structure of language can reinforce our cognitive categorizations without our having to actually experience anything new. By titling his movie Her, Spike Jonze has already established in our mind the female-as-object, which is all the more unsettling because the title itself seems to be part of the hype surrounding the film.

As I said before, language is the medium through which thoughts and ideas enter this world, and so the structure of the language necessarily affects the structure of the ideas it’s carrying, or at least restricts it. After all, cargo can only carry what fits in it, thus you can shove as many oddball characters into our first logline as you want, qualify it all you want, add quirkiness until its overflowing with bubble tea, but until you alter the underlying syntax, the result is always a male subject and female object. Anything else simply can’t be borne by it.

And this is why syntax actually matters. Our brain’s map of the world and its language are inexorably linked, meaning that if you change one you can change the other. By relying on the syntax of the old world to write our films, we limit its usefulness as an indicator of social progress. Think about it this way: how many movies can you think of whose logline is “A girl falls in love with a boy”? My guess is that, off the top of your head, you won’t be able to fill both of your hands (and if you do, they will probably all be from the 90s.) That logline still won’t sell as well as its inverse, and that is a reflection of how we continue to objectify women by literally reinforcing their placement as such in the syntax of our everyday lives.

Her, not She

There are arguments to be made about Samantha’s initial agency, and whether or not her programming would ever have allowed her to not fall in love with Theodore, but since the film is from Theodore’s perspective, it doesn’t really matter what Samantha wants. It doesn’t even matter that she ultimately gains enough agency to transcend and leave him, at least insofar as that transcendence is just the final step of Theodore’s maturation, the thing which pushes him to embrace the world again. She, as per her initial design, is just a tool for Jonze to use in telling the story of his subject. That her first act of true agency is also her ultimate act of usefulness to Theodore is exactly the kind of cruel irony that could only exist in an ultra-hipster science-fiction movie.

That, ultimately, is why Her is called Her and not She. She would be a film in which Samantha would be more than a literal and narrative tool, but Samantha has no place as the subject of this story, as manic-pixie dream girls rarely do. She has no place as a character worthy of equal introspection and desires; she simply exists as a narrative function to Theodore’s character arc. A more honest movie would have at least chosen the title of Samantha, giving its female-object a name, but not Her. Instead, Her essentializes the female-as-object and parades it on its posters.

In conclusion, I will share with you the collective logline of a few of my personal rom-com favorites, such as When Harry Met Sally, As Good as it Gets, and the Before Sunrise trilogy, and let you determine the syntactical difference:

A woman and a man fall in love with each other.

Richard Herbert is a is a writer and film geek living in Portland.