Is the Golden Age of Television really over? Andy Greenwald at Grantland seems to think so, as do some of Breaking Bad’s mourners. It’s true that some of our favorite prestige dramas have given way to less-good copycats: instead of The Shield, we now have Low Winter Sun; Deadwood and The Sopranos have turned into Boardwalk Empire. Mad Men is ending, so Masters of Sex began; Game of Thrones is on hiatus, so we’re stuck with the CW’s Reign.

Now if you ask me, reports of TV’s demise have been overstated. This year alone has given us Orange Is The New Black, The Americans, and Rectify, one of the most different programs I’ve ever seen on the picture box. I do, however, agree with Greenwald on one point: more diversity on the boob tube is always appreciated. I’m not just talking about racial diversity, though that always gets a thumbs-up from yours truly. I’m talking more about diversity of personality.

Basically, I’m experiencing asshole fatigue.

It’s hard, suffering from asshole fatigue.

I’m not the first person to express this opinion. Entertainment Weekly recently called TV’s newest antiheroes “anti-entertaining,” while The New York Post claims antiheroes have “jumped the shark.”

But what other choice do we have? Villains and morally-gray folk are simply more interesting than heroes. Look no further than The Vampire Diaries to remind yourself that Good Is Boring and Evil Is Sexy. Even John Milton knew that everyone prefers a bad boy. Batman’s cooler than Superman, Logan beats Piz any day of the week, Katara should have hooked up with Zuko, and Jess was superior to Dean. This line of thought applies equally to female characters: Why pick Betty when you’ve got Veronica waiting in the wings?

I bet you’ve heard these arguments before. I’ve definitely made all of them myself. But you know what? I am done with all that shizz. Here’s my new motto:

ALL. HAIL. THE LAWFUL GOOD.

I. Lawful Good: A Definition, A Defense

If you’ve never had the pleasure of playing Dungeons & Dragons, know that it operates on what’s known as the Alignment System. Players build characters around two axes: their morality and willingness to follow rules. Characters can be Good, Neutral, or Evil on the moral scale, and they can be Lawful, Neutral, or Chaotic on the rule-following spectrum. You can read more about D&D alignments here, but the following image illustrates the concept well:

And if Star Wars doesn’t do it for you, here are some Muppets:

If you have had the pleasure of playing Dungeons & Dragons, you probably know that few want to be Lawful Good. In my experience, most players want to be a loner rebel long on coat and short on scruples. Chaotic Neutral seems popular—that’s the Han Solo in A New Hope type. But there are some Neutral and Chaotic Good guys, too. That’s the Han Solo in Return of the Jedi type.

Nothing wrong with these characters. I love me some Han Solo. I just want to point out that they can be as dull as the dullest Lawful Good paladin. You want to play a rogue with a five o’clock shadow who shoots first and asks questions later? Sure, go for it! But we’ve all seen that guy before:

My point is this: A character’s alignment does not determine how interesting the character is.

Once more, with feeling? A CHARACTER’S ALIGNMENT DOES NOT DETERMINE HOW INTERESTING THE CHARACTER IS.

I don’t fault you if you don’t believe me. There’s this idea floating though the pop culture ether that Lawful Good characters are necessarily bores. You know, like Superman. QED. To which I say:

1. Who says Superman has to be boring?

2. Agent Cooper Agent Cooper Agent Cooper

II. Agent Cooper?

Indeed! If you’ve been following me on Twitter, you know I’ve spent the past month live-tweeting Twin Peaks 23 years after the fact. Its first half is one of the best and weirdest shows ever to grace the TV screen, and I continue to be shocked by its popularity back in the day. We talk about our current era as the Golden Age of Television, but I can’t imagine seeing something so oddball in 2013, let alone on ABC, of all places. David Lynch was on network television, people! You know: the Mulholland Drive guy? The director of Dune? And mainstream audiences loved it. The mind boggles. Forget the murder of Laura Palmer. This is the great mystery of Twin Peaks.

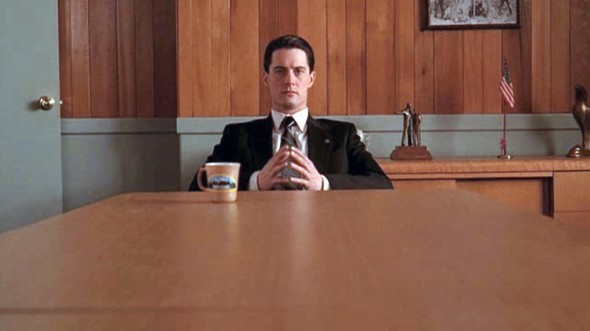

Anyway, Twin Peaks is a show loaded with wonderfully weird characters, most of whom are what we might call “morally gray.” There’s the Homecoming Queen with dark secrets, the kind mechanic who’s cheating on his wife, the biker rebel who is really just a big softie, the sheriff’s sweet girlfriend who is plotting to do… something. (Yeah, still not sure what Josie’s deal was.) Almost everyone in town is a morally-complex antihero, so naturally the most compelling character is the one with no moral complexity at all:

DAMN fine. Now who said good wasn’t sexy?

Oh, yes. Twin Peaks’ protagonist, Agent Cooper, is the big draw of the show and currently in the running for my favorite TV character ever. And right now, he is going to teach us how to write a Lawful Good character who is worth paying attention to.

III. How To Write the Lawful Good

1. Give ’em personality.

As I said above, there’s this idea that a lack of moral complexity means a lack of complexity, period. This isn’t necessarily the case. There is more to a person than whether or not he poisons innocent children. For example:

- Likes and dislikes. Make ’em unique. Our Agent Cooper dislikes birds and unreasonably-priced hotels. He likes black coffee, whittling, and the taste sensation when maple syrup collides with ham. Oh, and Douglas firs. Also he likes pie. He really, really likes pie.

- Life philosophy. Cooper is a Tibetan Buddhist… ish. When mindfulness fails to help him solve crimes, he’s not above resorting to magic. (Yup. Magic.) He also believes you should randomly give yourself a present every day, which is a brilliant life philosophy if I’ve ever heard one.

- Outlook. Just because you’re a hero who believes the forces of good should win, it doesn’t mean you always think good will win. Cooper, for example, is a fascinating mix of optimist and pessimist. He’s so idealistic he thinks Twin Peaks is, boy golly, the best place in the world (it isn’t), but he’s so cynical that he immediately assumes the fresh-faced Homecoming Queen was a cokehead. Twin Peaks’ Albert is an even better example. Though Lawful Good, he’s witheringly sarcastic and spends most of his time snarking at everyone he meets. But while he admits a “certain cynicism” (his words), he’s also a true pacifist who wants to change the world with love, à la Martin Luther King. Cynicism and Lawful Goodness, you see, are not mutually exclusive.

2. Make ’em funny.

I think people’s main problem with Lawful Good characters is that they can be humorless. Villains get to wear a smirk or crazed grin, but when we think of Superman we think of square-jawed determination. Big snooze.

It doesn’t need to be this way. Like I said, sarcasm and Lawful Goodness aren’t oil and water; there’s no law on the books that bans verbal irony. Nor are there laws that prevent heroes from cracking jokes of other kinds—Leslie Knope is Lawful Good and loves to laugh her delightful laugh.

A character can also be funny without trying to be funny. We imagine Lawful Good characters to be incredibly idealistic, polite, driven, rule-abiding, and earnest. Exaggerate any of these traits even slightly, and you have a hilarious character. First I will prove this point with a picture:

And now I will prove this point with a video:

And look, worst case scenario, just bring in a llama. Llamas: Never not funny.

3. Don’t make things easy.

Stories about Lawful Good characters shouldn’t be simple. In real life, good doesn’t handily beat evil like in a Saturday morning cartoon. It’s rough out there for a good guy (or gal), and so should it be in our fiction.

You’ve heard this tip before: Conflict can be the engine of a good story. As our own John Perich noted in his excellent piece on Man of Steel, even the Lawful Good can have internal conflicts. Their conflicts aren’t of the “Should I poison this child?” variety. Rather, they must choose between two or more competing values. In Dungeons & Dragons, the typical Lawful Good conflict is, “Should I break the law to do good?” Other conflicts can stem from questions like, “Should I save my loved one, even if it plays into the villain’s plan?” or “Should I do the right thing even if it will hurt my friends?”

In Twin Peaks, however, Agent Cooper has few internal conflicts. He’s not an internal guy; his entire train of thought is constantly being spewed out onto a cassette tape. But the show works, because the external conflict is a doozy. The heroes are going up against a super-complex mystery and the kind of evil that might not be possible to beat. At one point the Lawful Good Major Briggs says his greatest fear is the possibility that love is not enough. Twin Peaks works despite its impossibly pure protagonist, because it’s about how the purest love and goodness may not be enough to defeat humanity’s basest instincts.

In short, a Lawful Good hero has to lose—not all the time, but sometimes. Maybe even most of the time. (See also: To Kill A Mockingbird.)

4. Cool clothes and weapons don’t hurt.

I don’t know about you, but I’m a sucker for a good suit and skinny tie. And, as Atticus Finch taught us, you don’t have to be evil to be a badass with a gun.

Biggest badass in fiction.

5. The rule I decided to delete.

My last guideline for writing Lawful Good characters was going to be, “Give your character flaws.” You know I’m all about flawed characters. I wrote all about them in my piece on Strong Female Characters.

Then I realized, Twin Peaks completely destroys this rule. Agent Cooper literally has no flaws. One of the characters actually says to him, “You know, there’s only one problem with you: you’re perfect,” and he doesn’t disagree. It’s not him being boastful. The statement is objectively true.

The funny thing is, in the crappy, later parts of the second season, the writers (sans Lynch) awkwardly tried to give Cooper flaws and retcon in a dark backstory, and this somehow made him a less compelling character. To avoid spoilers I’m not going to go into detail, so suffice it to say that the writers gave him the Obvious Lawful Good Flaw: a savior complex. Because of his Obvious, Clichéd Cop Backstory, he developed the flaw of having to save young, troubled damsels. Tell me if you’ve heard that one before.

So, after some thought, I guess my new guideline is this: Give your Lawful Good characters flaws, or don’t, but try to avoid the obvious ones. If you feel you must use a cliché, at least playfully wink about it, Lynch-style. But promise not to wink backwards like Laura Palmer does. You’ll give us all night terrors.

IV. Why Lawful Good?

Now that we’ve talked about how to write Lawful Good characters, I’d like to end by talking about why we might write them. It’s not just so you can entertain me, the one fatigued by assholes.

This might be my secret idealism talking, but I think most people in the world are trying to be lawful and trying to be good most of the time. Most people will never kill someone, even if they’re police officers or in a war. Despite what Mad Men would have you believe, most married people do not cheat. And statistics show that the majority of weddings do not end in epic massacres.

People aren’t always good, obviously, but it seems like we usually try to be. And I think (and most dearly hope) that most people would prefer to be Agent Cooper or Leslie Knope than Walter White. Most people’s daily struggles are not about how to keep their international drug empire from crumbling but how to survive and keep one’s moral compass in a dog-eat-dog society. Is this struggle not the stuff of high art? Is it only worthy if a character makes the “evil” choice? And by saying the Lawful Good are boring, are we implying normal people are not worth paying attention to?

I am not, of course, saying that we should give up our villain protagonists and antiheroes. What I am asking is that we consider shows with Lawful Good protagonists as potential additions to the Golden Age canon. If films like To Kill a Mockingbird, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It’s a Wonderful Life can be as acclaimed as The Godfather and Bonnie & Clyde, why is it that shows like Friday Night Lights and Gilmore Girls are often ignored in discussions of great 21st century TV? Is it because the shows aren’t horrifying? Is it because their characters are too decent?

So, last question: Is the Golden Age of Television really, truly over? Maybe, if it means shows about jerks and criminals. But one might consider for our Best Of lists Broadchurch, Parks & Recreation, and even Adventure Time, all current shows with (mostly) Lawful Good protagonists. And maybe Lawful Good is the best way forward for prestige television. In our current glut of TV antiheroes, a real paladin could be a revelation.