(Enjoy this guest post by Richard Herbert. – Ed.)

We must understand it not as reason diseased, or as reason lost or alienated, but quite simply as reason dazzled.

–Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization

In 1938, Americans who tuned into Mercury Theater on Air’s Halloween program a bit late listened with rapt-attention and evolving terror as their radio-broadcast ostensibly reported the invasion of Earth by Martians. Of course, had they tuned in a few minutes earlier, they would have heard the program’s disclaimer identifying the work as a radio drama; a drama that used the format of news broadcasting to tell a science-fiction story. The panic that ensued, though probably not as great as the newspapers of the time would have us believe, was an example of a rational response to an imagined situation. After all, Orson Welles and Co. had carefully studied Herbert Morrison’s reporting of the Hindenburg disaster, and the broadcast ran without the commercials listeners would expect from a radio drama—all to increase the production’s sense of realism. Furthermore, this was during America’s peak alien fervor, well before better observation of Mars had discredited the supposed “Martian canals” and failed to reveal any evidence of intelligent life or civilizations on the Red Planet’s surface (Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles was still over a decade away).

In 1938, Americans who tuned into Mercury Theater on Air’s Halloween program a bit late listened with rapt-attention and evolving terror as their radio-broadcast ostensibly reported the invasion of Earth by Martians. Of course, had they tuned in a few minutes earlier, they would have heard the program’s disclaimer identifying the work as a radio drama; a drama that used the format of news broadcasting to tell a science-fiction story. The panic that ensued, though probably not as great as the newspapers of the time would have us believe, was an example of a rational response to an imagined situation. After all, Orson Welles and Co. had carefully studied Herbert Morrison’s reporting of the Hindenburg disaster, and the broadcast ran without the commercials listeners would expect from a radio drama—all to increase the production’s sense of realism. Furthermore, this was during America’s peak alien fervor, well before better observation of Mars had discredited the supposed “Martian canals” and failed to reveal any evidence of intelligent life or civilizations on the Red Planet’s surface (Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles was still over a decade away).

Therefore, listeners who thought the broadcast was real, keeping in mind the lengths Welles and his cadre of performers went to in order to present a “real” experience, were not necessarily acting irrationally when they made frightened phone calls to the police, or peered out their windows to catch a glimpse of spaceships in the sky. But these reactions, though rationally justified, were nonetheless within the confines of a very convincing illusion: there were no spaceships, only the suggestion of them.

Another, similar urban legend alleges that during the first screening of L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, a nineteenth century documentary short film of a train pulling into a station, audience members went screaming through the aisles in panic, due to the realism of the film and the unfamiliarity most people of the time had with motion pictures. While, again, accounts have probably been exaggerated (or confused with a later, stereoscopic viewing of the film), they nonetheless highlight the fine line between reality and a convincing illusion.

Another, similar urban legend alleges that during the first screening of L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, a nineteenth century documentary short film of a train pulling into a station, audience members went screaming through the aisles in panic, due to the realism of the film and the unfamiliarity most people of the time had with motion pictures. While, again, accounts have probably been exaggerated (or confused with a later, stereoscopic viewing of the film), they nonetheless highlight the fine line between reality and a convincing illusion.

But how do you describe a physical response to what is clearly imagination, perfectly reasoned as it may be for the person doing it? It is not irrationality, because if you are convinced of an alien invasion or that you are about to be flattened by a train, action is the only rational response. But neither is it exactly reason: a better sense of judgment should keep a person from being fully convinced of a false image in the first place, even intuitively. To find the answer, we might look to Madness and Civilization, Michel Foucault’s first major work, wherein he describes the history (or at least his version of it) of the relationship between madness and European society, from the Middle Ages through the end of the Age of Reason. In doing so, he proffers both an extensive examination of how different periods have viewed and reacted to madness, as well as his own, more general definition of what makes someone mad:

All that madness can say of itself is merely reason, though it is itself the negation of reason. In short, a rational hold over madness is always possible and necessary, to the very degree that madness is non-reason. There is only one word which summarizes this experience, Unreason: all that, for reason, is closest and most remote, emptiest and most complete; all that presents itself to reason in familiar structures—authorizing a knowledge, and then a science, which seeks to be positive—and all that is constantly in retreat from reason, in the inaccessible domain of nothingness.

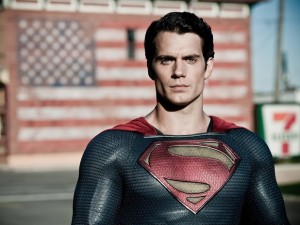

Foucault believes the mad person is not without reason; in fact, he believes the “language of madness” to be rationality itself—a rationality that has accepted the imagination, or delirium, as truth. So it is interesting to think how he might have scrutinized someone like David S. Goyer, the writer and producer of Man of Steel and The Dark Knight trilogy, who has expressed his desire to create films depicting superheroes in our own world—to create the illusion of gods with mystical powers, or rich men who become godlike idols, fighting for justice in the streets of Chicago or New York. Is this cinematic chicanery, the attempt to portray a realistic Superman or Batman, so far removed from Orson Welles’ desire to scare his audiences into believing Earth was being invaded by Martians? Perhaps not.

Foucault believes the mad person is not without reason; in fact, he believes the “language of madness” to be rationality itself—a rationality that has accepted the imagination, or delirium, as truth. So it is interesting to think how he might have scrutinized someone like David S. Goyer, the writer and producer of Man of Steel and The Dark Knight trilogy, who has expressed his desire to create films depicting superheroes in our own world—to create the illusion of gods with mystical powers, or rich men who become godlike idols, fighting for justice in the streets of Chicago or New York. Is this cinematic chicanery, the attempt to portray a realistic Superman or Batman, so far removed from Orson Welles’ desire to scare his audiences into believing Earth was being invaded by Martians? Perhaps not.

Nearly no one above the age of ten believes that Superman or Batman is real, but surely critics’ comparison of The Dark Knight to Heat will alone illuminate the how far society has come in sublimating supernatural and/or mythical icons into the roles of gritty action heroes. A look at recent or upcoming movies based in the Marvel or DC universes, such as The Wolverine, Man of Steel, Thor: The Dark World, and even Iron Man 3, betrays a similar conceit for any superhero adaptation with literary aspirations: by placing superheroes in a grimier, darker, more realistic world, viewers will be more “immersed,” and therefore more entertained. This is where Foucault’s distinction between irrationality and unreason becomes most clear. As he states: “Meaningless disorder as madness is, it reveals, when we examine it, only ordered classifications, rigorous mechanisms in soul and body, language articulated according to a visible logic.”

Life is a volatile and turbulent first-person experience—a perpetual shaky cam of linear perspective that, permitting the occasional jump cut after a few too many drinks, happens in real time, all the time. Narrative entertainment—or any entertainment that uses thematic and/or theatrical elements to tell a story—functions differently. Though having long evolved from the cave-paintings of antiquity, wherein stories were told through a sequence of simple pictures, modern forms of entertainment and theater never really lost the core of that ancient form: the static chronology, the implied distance between form and idea, the jumping back and forth through time. Early petroglyphs were not documentation, in the way that early Linear B tablets were, but communication: whether to lament the futility of human existence, indicate the fertility of a particular site, or teach the best ways to kill a boar, “motion pictures” told a story.

But the inclination to thrust larger-than-life, supernatural, or otherwise improbable characters—particularly superheroes, but this could be true for any number of “re-imaginings” popular in Hollywood for the past few decades—into a realistic environment damages the metaphorical value inherent in these stories’ origins. The Batman comics, or cartoon-series, are drawn pictures, representative of actual life only insofar as our imaginations and the intentions of the artists allow. You will never mistake a comic for reality, and how much that world can exist in your mind is entirely dependent on your providing pictures with metaphorical or representative value, all of which happens autonomously in your head—all of which requires you believe things can have metaphorical value in the first place.

In film, though, this is a little different. No one walks out of Man of Steel, or The Dark Knight Rises, believing the events that happened are real. But one might walk out and say, “That was a realistic superhero movie.” Rationally, those words are preposterous, but that is nonetheless what David Goyer and Christopher Nolan want to happen. They do not want you to look at their Gotham and see dark spires a la early German expressionism, nor do they want to embrace the ridiculous camp of the original TV series or the dark, extremely over-the-top satire of the Tim Burton/Joel Schumacher films. They want you to see the streets of Detroit, of Chicago, of New York; they want you to see in the Falcone family’s seedy underbellies real-life crime cartels; they want you to believe Batman could actually exist, given the right circumstances.

Even Man of Steel succumbs to this kind of absurd rationalization, what Foucault calls “rigorous mechanisms”: although all of the explanations are dubious at best, ridiculous at worst, there is a constant flow of “scientific,” or at least rational, justifications for Superman’s powers, his homeland, and his costume. To Foucault, madness is not imagination, but the acceptance of imagination as truth: “But while error is merely non-truth, while the dream neither affirms nor judges, madness fills the void of error with images, and links hallucinations by affirmation of the false. In a sense, it is thus plenitude, joining to the figures of night the powers of day, to the forms of fantasy the activity of the waking mind; it links the dark content with the forms of light.”

Even Man of Steel succumbs to this kind of absurd rationalization, what Foucault calls “rigorous mechanisms”: although all of the explanations are dubious at best, ridiculous at worst, there is a constant flow of “scientific,” or at least rational, justifications for Superman’s powers, his homeland, and his costume. To Foucault, madness is not imagination, but the acceptance of imagination as truth: “But while error is merely non-truth, while the dream neither affirms nor judges, madness fills the void of error with images, and links hallucinations by affirmation of the false. In a sense, it is thus plenitude, joining to the figures of night the powers of day, to the forms of fantasy the activity of the waking mind; it links the dark content with the forms of light.”

Therefore, even if one walks out of the theater confident in their grasp of reality, one might see the film-going experience (presuming one was engrossed by it) of watching superheroes portrayed realistically as a kind of temporary madness, shared communally by everyone in the theater. Movies these days might be more comparable to amusement park rides than to stories, but they have the unique ability to present realistic images—Foucault’s delirious images—using chicanerous production techniques that inundate viewers with a sense of being a part of something real. Man of Steel loves its shaky-cam, and the Dark Knight loves its plausibility. But when, in the history of all things sensible, did someone say, “I want a realistic superhero movie?”

Children often play superhero, standing atop the slide or fort, hands on their hips, pretending to be a caped crusader. The act of pretending is not itself an act of madness, but a kind of wish-fulfillment. Similarly, teenagers and twenty-somethings, however subconsciously, want to see their moral and physical paragons—vulnerable but undefeatable; complex but ethically inexorable—walking their streets, not the streets of some fantasy world. The metaphorical value of the superhero is lost because a metaphor requires an assertion of will on the part of the viewer–a belief that there is value beyond an image. Hollywood is teaching us that you cannot inspire people by metaphor alone anymore–you must convince them, if only for a couple of hours, their heroes are tangible. Not hidden somewhere in our hearts, not a symbol for the hope held in every person, but actually walking the streets; cloaked by moral penumbra; lurking in Detroit, Chicago, New York; keeping people safe in these turbulent times.

The ultimate language of madness is that of reason, but the language of reason enveloped in the prestige of the image, limited to the locus of appearance which the image defines. It forms, outside the totality of images and the universality of discourse, an abusive, singular organization whose insistent quality constitutes madness.

The act of hope is an act of imagination—the ability to perceive a future better than your current circumstances. Hollywood, instead of asking people to question their perceptions and take part in the act of imagination, the act of of hope, now simply says, “Sit back, let us do it for you.” All the metaphorical work has been taken on by the image itself, insisting that we, as the audience, should not question the truth of it, but become subsumed by its truth. One can see the movie theater itself as a modern place of confinement–a madhouse, if you will: you are not to question reality, your circumstances, or imagine something greater than yourself while you are here, because you don’t need to. “Your gods are real. They walk your streets,” the director of L’Hôpital de Cinéma says, stroking your hair, comforting you in your white, palate-less cell.

“Everything is fine.”

Richard Herbert is a freelance marketing writer and film geek in Portland, who spends most of his time drinking coffee and over-analyzing pop culture.

Just because one aspect of a story is unrealistic doesn’t mean all other aspects must be equally unrealistic to match; indeed, a story consisting entirely of unrealistic elements would be very difficult to make any sense of at all. I think you are certainly overthinking the potential problems in making slight adjustments to exactly how much unrealism is where in the current crop of movies.

The movies were perfectly functional with pre-Batman Begins levels of unrealism. It appears that a choice was made to strip away any unreality not essential to the premise, and the question is Why?

In a movie about a wealthy orphan who dresses up as a bat and fights crime, or an alien who is functionally human except that for handwave-y reasons has super strength and can fly and has heat vision, how is reality the enemy?

There is no doubt I am overthinking it–indeed, it’s the point. But BastionofLight makes the salient point here, I think: these movies strip away so much unrealism it’s weird they retain any of the superhero at all. There are plenty of stories grounded in this universe with similar themes that could be told, so it’s hard not to see this trend as anything but a deliberate attempt to repurpose fantastic idols for entertainment purposes.

But I think there’s a reason why the old model doesn’t work anymore–now that this more experiential, less literate version of superhero has been unleashed, people seem to not be able to go back. It’s this weird In the Mouth of Madness situation, or one of those movies where beloved characters start popping up in real life to the surprise of everyone in America. It’s just that these superheroes are popping up on 2D screens, but the act of “bringing them to life” is still very palpable. Seems like madness to me.

I agree, comic movies are going for grittier and more realistic. So to push it further into the realm of why, we can apply your explanation to comics themselves first. Because the movies are actually behind the comics- Fraank Miller had already written some of his “gritty” stories about Batman and Daredevil by the time Burton literally came on the scene; there was Watchmen in 1986; and just before Batman Begins, Jeph Loeb came onto the scene for Batman, and Mark Millar came up with Red Son (a very dark Superman story). My examples are DC, but Marvel has gone that way, too- heck, even Dark Horse and some if its titles like Hellboy took “realistic” turns before the wave of comic movies, starting with X-Men in 2000, became more “realistic” and less, well, comic-ee. While most of the New 52 in DC have kept up the gritty realism, so too have other publishing houses. And the movies are continuing on that trend.

(Sidenote: And this is one of the huge arguments against a Wonder Woman movie, that her backstory is too “fantastical” and “not believable enough,” despite friggin’ Thor getting his own series. So she hung out with Aphrodite and Athena and kicked Ares’s butt a few times, big deal! But this isn’t about the effed up gender politics of geekdom. Sorry.)

I think generally, though, the question of, “Why?” is important. WHY do comic writers/artists and film makers want to immerse their audiences in this particular way now? Why did it start? Why has it picked up so much?

And I’d like to ask you, do you think they feel this Fruedian immersion and self-imposed madness is necessary in order for people to care about superheroes now? Or do you think the producers of comics and films are trying to tell us that in order to push what they want on us?

I think it’s postmodernism’s doing. The Watchmen is a perfect example-Alan Moore wanted to subvert the genre, so much of which had been unexamined fluff.

Modernism gave us big dreams. Post-Modernism set in when we realized that things wouldn’t be that easy, and that with great progress came great problems. (Nuclear power, yay! Chernobyl. Boo! We’re on the moon! Yay! So what? Boo!)

I adore the Nolan Batman movies, but I also love the old Adam West series (though as an adult, I see that the latter is more self aware that I used to give it credit for. But it certainly didn’t go in for much character depth.) Certain characters, like Batman, are so popular because there is such a range of style and substance to explore. The best characters are the ones who can handle the postmodern poking stick.

I think the Avengers movies are a good example of finding a synthesis. Heck, we could probably use Captain America as a metaphor for the whole thing–he represents the inspiring spirit of patriotism/wonder/We Can Do It, and after sleeping for a long time, he’s back to inspire again.

It could be a case of moving our goalposts for what constitutes “realistic.” Currently, we’re in the midst of a long-standing economic downturn, post 9/11 US people distrust their government a lot more, etc., which might mean there is overall a more negative outlook on the world in general. Which is not to say that the world is worse now than it was decades ago, or that people didn’t have problems in the 60’s, 70’s, etc., but maybe people are more aware of the negative side of things now. I wonder if, in another 5-10-15 years, there will be a backlash against the grim and gritty style as being overly cynical, and if there will be more optimistic films being made that will be considered more realistic than their overly melodramatic and dark predecessors.

I believe it has been a relatively natural evolution–a confluence of things–leading to this stylistic change in superhero movies. I don’t think it’s fitting to blame post-modernism because post-modernism’s not new. Tim Burton’s Batman was right smack in the middle of the post-modern movement, although I suppose it could be that those higher-art tendencies are only now trickling down into the mainstream.

Still though, it’s not hard to make a connection to the Nolan era of Batman movies and the general lack of faith people young and old alike have in the structures of society these days. The Bush era, the collapse of the economy, the continuing farrago of the political system seems to leave people without something firm to hold onto. We like to see gritty movies because, in a way, they reflect the chaos and uncertainty of our ideological circumstances.

On the more “it just happened” side, though, Michael Mann and Steven Soderbergh had a lot of influence in the 90s and early 2000s, and it’s pretty easy for me to see their proteges (like Nolan) applying their signature “gritty” techniques to increasingly popular blockbusters, which is probably a big part of it, too.

I think that the increasing level of realism isn’t necessarily reflective of a growing desire for escapism/shared madness/virtual reality any more than the transition in literature from mythic splendor to Russian novel realism is indicative of these things. The people are given huge proportions in each of these mediums, both to make them more entertaining in their feats and more readily analyzed in what they represent– we can see them more closely precisely because they are larger than life.

In the Brothers Karamazov, the sons of Fyodor Pavlovitch represent unrealistically pure components of humanity: mind, body, spirit. In The Dark Knight Rises, Batman can take incredible amounts of pain, lives the life of a playboy billionaire, and has an unwavering allegiance to humanistic ideology against Joker-esque nihilism. Each of them are quite unlikely, but equally they allow for an examination of human principle and human action in dire circumstances– like a philosophical thought experiment of sorts.

And while I’m not certain if the questions that are asked of these characters somewhat debase the premise upon which they are asked (in a world in which these people and events are possible, are we even talking about the same ideologies which belong to the less than superhuman?), I think that in essence these forms of media strive for roughly the same thing, using roughly (and I mean roughly) the same techniques.

Several times this post and again this comment made me think if the novel Dracula.

When talking of madness and reason, crossing the lines of reality, and using realism to bring the supernatural to our world… it’s a very fitting touch point.

Stoker’s style was very clearly chosen to mimic the letters and travelogues that his audience would be familiar with.

It’s actually hard to say whether good movies or good books are the strongest conduits for temporary madness.

A fascinating difference to ponder is the way that movies reach out to create a simultaneous delusion in a crowd. No wonder religion and politics are always obsessed with film/TV.

The problem is that something like The Brothers Karamazov was written to stand on its own, whereas this new wave of superhero movies is attempting to force what is already canon into a totally divergent framework. Which is fine, but this new framework, being ostensibly founded in “reality,” is incredibly limited, and the elements its receiving–the Joker, the Scarecrow, Superman, General Zod–are blunted of any aspect that cannot squeeze through.

I understand this is not new for comics, but comics continue to exist in worlds where you can entirely define the rules. Frank Miller’s original comics are grittier and more realistic, yes, but they are still in a carefully constructed universe of grit and real, not necessarily related to the world in which we live. Nolan’s undertaking was to essentially film Batman in OUR universe, not some comic equivalent. Gotham looks like New York, or Detroit, or Chicago, because it is all of them (depending on the movie).

There is no doubt that there is an element of thought-experiment to all of this, but the thought experiment is itself a kind of rigorous mechanism. The whole point is that superheroes don’t exist to be real, they exist to be fantastical, metaphorical, inspirational. Any effort to bring them down to our level should be met with a raised eyebrow, because it re-purposes them not to inspire us, but to, in some way, actually protect us.

Or, at least, make us feel like they have.

Within the diegetic framework it’s interesting to see how the characters themselves seem to accept the absurd and ludicrous.

I can think of a few exceptions to this in the film/comic world where the absurdity is questioned.

The stoner in Cabin in the Woods definitely questions the absurdity of the reality that all other characters seem to accept.

In the Comic world Deadpool frequently breaks the 4th wall and directly addresses the reader, questioning the reality in which he finds himself.

It’s interesting how a character has to be high or completely insane to see the absurdity in which they find themselves.

Not totally on-topic, but your comment reminds me of high school English class, in which my teacher noted that in Shakespeare’s plays, noble characters usually speak in iambic pentameter – except for the ones who are insane, who speak in free-verse.

::nervously clears throat::

Well, actually, the free-verse vs. iambic pentameter setup in Shakespeare was along class lines- so you’re right about the nobles being fancy, but it wasn’t just “insane” characters speaking in free verse. Anyone that didn’t have a title or whose purpose was comic relief (and very rarely would nobles be comic relief) would speak in fee verse.

But, your comment does bring up a funny paradox: The nobles all sound kind of off, while everyone else sounds normal. Because nobody actually walks around speaking with a deliberate meter in everyday conversation. So the nobles are the ones that come off weird.

But no, the meter didn’t depend on sanity levels- lots of nobles go mad over the course of a given play and keep speaking pretty- Lear, Macbeth (and Lady Macbeth), Othello, Ophelia, Cleopatra, Brutus…

You also allude to the comment I was going to respond to Falconer with, anyway, though, which is that Shakespeare frequently used the “wise fool” trope in his plays- invariably, the jester/fool character would actually show some impeccable insight as to what was really going on, making commentary about the characters or foreshadowing what was to come in an almost-fourth-wall-breaking fashion. Which very much fits the “reason in insanity” thing- the characters that were “crazy” on the surface were actually the most keen ones.

Christopher Moore wrote Fool, a few years ago, actually. It’s a parallel novel from the perspective of the jester in King Lear, and the entire book is an extension of the wise fool thing- the jester is painted as the one pulling the strings and the reason everything in the play happens. I don’t think Shakespeare meant for it to go quite that far in his plays, but the inch leading to the extra mile gone by Moore is certainly pretty obvious in the original.

Cabin in the Wood’s ideological predecessor, Funny Games (by Michael Haneke), is actually a pretty good epistemological analysis of how and why we watch movies. Haneke put me onto that question in the first place, and anyone who hasn’t seen it should. It’s point isn’t subtle, but it’s actually a good companion piece to this article. When you actually analyze it, you find all of these levels of reality and unreality, a place where they converge, and what happens when they do.

The reference from Foucault reminded me of a quote, I hoped to find it when I got home but it eludes me so I’ll paraphrase:

“The way to understand the mind of a psychopath is to take away every human trait except rationality.”

I’m sure it wasn’t a direct quote from Foucault, but it really seems influenced by him.

I like it because it reminds me to keep a check on my tendency to intellectualize without compassion.

And it makes sense. Not that I’ve known any Psychopaths personally (a few sociopaths but that’s a different story), so at least I’ll say it makes sense in it’s fictional applications.

example: If delirium states that the path to heightened reality is “absorption” of another, then rationality states ‘Get a psych degree and stock up on Fava Beans’.

Not really, psychopaths aren’t rational people when subject to frustration.(Sociopaths are) The best fictional exemple of a psychopath is Begbie (played by R carlyle)in Trainspotting.

Many Tv psychopaths are wrongly portrayed. (I see psychopaths almost everyday in my job ;) )

Sorry for my poor english, im a foreign speaker

Isn’t this one of the main themes of Don Quixote? The otherwise rational man who suffers from the (improbable) insanity of interpreting the world around him as if it were a romantic/chivalric novel, with himself as the protagonist knight. But the difference with said novels is that it’s made very clear he’s not living in a world of heroic knights, noble lords, evil villains and damsels in distress… the audience can see he’s talking to innkeepers, prostitutes, and upper-class people making fun of him. And of course, despite making a worthy attempt to be a paragon of virtue, Don Quixote is not himself a skilled or powerful fighter. So when he charges in to rescue what he sees as a innocent being attacked, the real, ‘gritty’ world intervenes and he gets beaten up.

The otherwise rational man who suffers from the (improbable) insanity of interpreting the world around him as if it were a romantic/chivalric novel, with himself as the protagonist knight.

There’s probably an OTI article to be written that compares Don Quixote to Abed Nadir of Community. I’d be on that if I had a better command of Don Quixote.