For those Overthinkers who aren’t familiar, the Bechdel Test is a critical rule of thumb that can be used to analyze the portrayal of women in a given film or other dramatic work. The test is simple. In order to pass, there must:

- Be two women

- Who have a conversation

- About something other than a man.

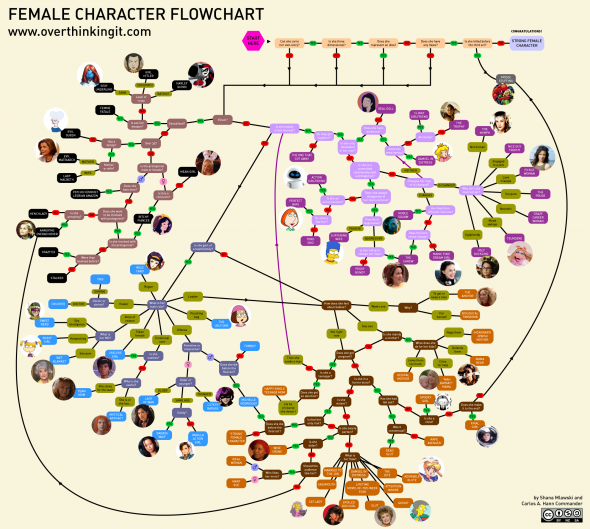

Do a quick mental inventory of your favorite movies and TV shows: odds are you will find that, it’s actually surprisingly rare for a movie to pass the test. As a critical tool, we here at Overthinking It are big fans of the Bechdel Test – it has featured regularly in various articles here on OTI, including one of our all-time most popular, the Female Character Flowchart.

As I’ll argue later, the Bechdel Test is interesting because it seems so reasonable – such a low bar to clear – that when movie after movie fails, it’s genuinely interesting.

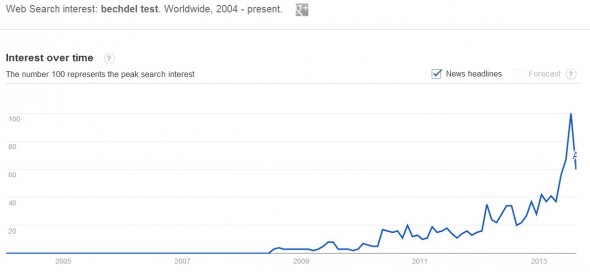

In the past few weeks, the public profile of the Bechdel Test has increased dramatically. The test itself is hardly new – it was invented for a comic strip in 1985, and there’s an internet database that catalogs whether movies pass or fail the test. For some reason, however, in the last few weeks, the test has suddenly been everywhere.

Google Trends, August 27, 2013

Part of the driving factor for the renewed interest in the Test is a handful of attempts to fashion similar critical tools that can be applied in other contexts.

The “Bechdel test for _______.”

While it’s always impossible to pinpoint exactly where and when something like this took root, it arguably started with a post at Vulture, “Does Pacific Rim have a Woman Problem?”,. The article called Rim out for its portrayal of women, citing (in one part) the Bechdel Test as evidence of the movie’s poor portrayal of women.

Some people, however felt that this was overly harsh – that the character of Mako Mori was a strong representation of women in general and Asian women in particular. In response to the article specifically and the Bechdel Test more generally, the author proposed an alternative to the Bechdel Test, called appropriately enough the “Mako Mori Test.”

What’s interesting about the Mako Mori is the motivation behind it – the author, Tumblr user Spider-Xan, identifies strongly with Mako as a “well-written Japanese woman who is informed by her culture without being solely defined by it, without being a racial stereotype, and gets to carry the film and have character development.”

Also popping into the public consciousness at about the same time is the “Vito Russo” test, essentially a Bechdel Test geared specifically for LGBT portrayals in film and television. More formalized than the others, the Vito-Russo was used in a recent report by an LGBT advocacy group to call out films and TV shows for their portrayal of LGBT characters, assigning them a “Studio Responsibility Index.”

Also trying to cash in on the trend, Slate ran with an article about a so-called “Bechdel Test for Higher Education Disruption.”

So for whatever reason, the Bechdel Test has hit the mainstream. What I want to talk about here is what makes the Bechdel Test interesting in the first place – and why I think the “alternative” Bechdel Tests I list above are ultimately less satisfying.

Before I get to far in, a quick qualification – the Bechdel Test is not the be all end all of criticism, or even feminist criticism. And while I will criticize the Vito-Russo and Mako-Mori tests as I go on in this article, the criticsm I’m leveling is a very narrow one – promoting positive portrayals of LGBT characters or minorities is a worthy goal, and trying to create critical tools to do so can be valuable. Rather, I just want to see how these tests stack up to their supposed inspiration.

Why is the Bechdel Test useful?

The first thing that’s important to observe about the Bechdel test is that the elements are for the most part objective: You don’t have to make value judgments to decide whether or not a given film contains one of the elements. You can argue a bit around the edges (Is the conversation long enough? Isn’t the subtext of the conversation about a business deal really about the love triangle the two women are involved in?) But for the most part, a movie either passes or it doesn’t, and most people can agree on whether it passes or not.

Second, not only are the individual elements of the Bechdel test objective, but the test itself is non-subjective. It’s hard to tell based on some of the rhetoric that often accompanies it, but the Bechdel Test itself imposes no normative judgments on a work for passing or not-passing – that’s done entirely by the user.

Third, while the test itself is non-normative, the test is still useful, the normative conclusion is obvious. It goes essentially without saying that the REVERSE Bechdel test is hardly ever failed – it’s EXTREMELY difficult to come up with a movie in which there isn’t at least one conversation between two men about something other than a woman (believe me, I’ve tried). But we know that in real life, that’s not the case- we expect that there are roughly the same number of women talking to other women as there are men talking to other men. Movies have a tendency to reduce the agency of women, trivializing the equality of their internal life – but that’s a hard concept to put your finger on. With the Bechdel Test, it’s easy to jump from the “What” to the “So what.”

Lastly, the Bechdel Test is valuable precisely because it’s limitations are so obvious. Because the elements are so simple, we can tell right away that it’s not going to be useful to talk about every movie. Does Saving Private Ryan pass the test? No. Does that mean that we should reject it as a bad movie? Of course not! There are many movies that pass the Bechdel Test that aren’t particularly feminist (Transformers: Dark of the Moon, for example), and many movies that DON’T pass the Bechdel test that are great exemplars of feminist thought. The test is so transparent, so it’s easy to see why the test doesn’t quite work in a given situation.

Pictured: Feminism

Which brings me to the “alternative” Bechdel tests above. Let’s break them down a bit and see how they compare to their inspiration:

The Vito Russo Test for LGBT characters:

1. The film contains a character that is identifiably lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender (LGBT).

OK, this one isn’t bad. I suppose that we can sometimes quibble about being “identifiably” LGBT since in some cases it’s left deliberately ambiguous, but this is certainly no more arbitrary than in anything in the BT. So far, so good.

2. That character must not be solely or predominantly defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity (i.e. the character is made up of the same sort of unique character traits commonly used to differentiate straight characters from one another).

We’re starting to get more subjective here. What does “solely” mean here? What kind of traits are “commonly used to differentiate straight characters from one another” mean? But this is still not too bad – while it might be hard to prove that a character PASSES this test, it’s pretty easy to tell when a character FAILS this test by being just “the gay one.”

3. The LGBT character must be tied into the plot in such a way that their removal would have a significant effect. Meaning they are not there to simply provide colorful commentary, paint urban authenticity, or (perhaps most commonly) set up a punchline; the character should matter.

What? This seems hopelessly arbitrary to me. Take the Ewoks out of Return of the Jedi and the Empire wins the battle, but that doesn’t mean that the Ewoks are particularly great characters. Alec Baldwin’s character in Glengarry Glen Ross wasn’t even in the play, and you could take him out of the movie without skipping a beat – but that doesn’t mean it’s not one kick-ass character.

Pass the Bechdel Test: A new Cadillac. Pass the Vito Russo test: a set of steak knives. Pass the Slate “Higher Education” test: you’re fired.

Note also the use of normative language – “must” in #2 and #3, “significant” and “matter” in #3. What does it mean for a character to “matter”? As far as I can tell, this is basically just another way of saying “LGBT characters should have more lines.”

Which, of course, there’s nothing wrong with! There’s nothing wrong with saying that LGBT characters should, in fact, have more lines. My issue is dressing what is essentially conventional critical analysis in a fancy-sounding title.

Even leaving that to one side, I would argue that the test lacks the intuitive normative implications of the Bechdel Test – if a movie fails the Vito Russo test, what are we supposed to take away from it?

The Mako-Mori Test for Female Characters:

The film must contain:

a) at least one female character;

Again, OK so far.

b) who gets her own narrative arc;

Starting to veer a little bit of course.

c) that is not about supporting a man’s story.

Kaboom. While this is a little easier to define than the VR test above, I think the MM test is still needlessly subjective. What exactly does it mean for an arc to “support the man’s story”?

I’m not even 100% sure that Mako Mori really passes this test – while she does get her own back story and character arc, most of her movie is spent linked to a man in a neural network to that they can fight robots in the face – culminating in a scene where said man punches a monster in the face without needing the help of Mako Mori. Of course, there are other ways of looking at it, but I think these last two elements don’t lend themselves to the kind of “True/False” analysis that makes the Bechdel test so effective.

The Slate article, I won’t even get into, since it’s really just a list of five things that the author thinks people should be talking about. Which again, that’s totally fine, but there’s no reason to drag a perfectly good Bechdel Test into your argument.

At this point, if you’re paying attention, (or just looking to be contrarian), you’ll notice that I’ve been subjecting these would-be Bechdel Tests to a standard that is every bit as squishy and subjective as those that I’m criticizing. I have two responses.

First: shut up, I’m not claiming that ALL criticism has to be subjective. In fact, the Bechdel Test is notable and rare precisely BECAUSE of it’s objective nature. Most critical analysis ISN’T broken down by discrete points, and that’s a good thing. I have no problem with using the criteria of the Vito-Russo Test or the Mako Mori test as a jumping off point for a discussion of literature – but calling it a “test” implies a false level of objectivity.

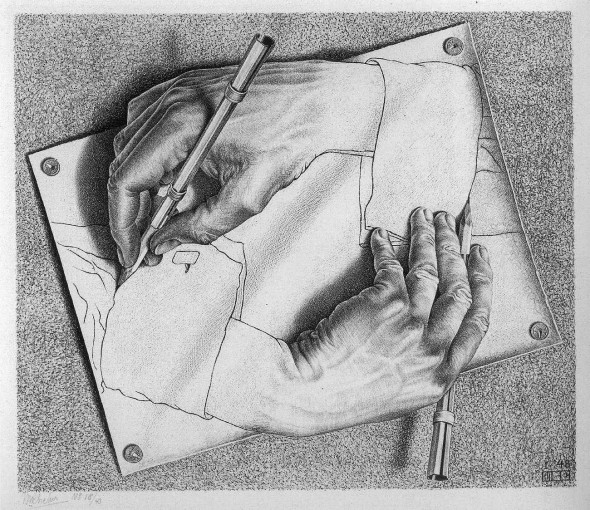

Second: OK, good point. What I clearly need is a Bechdel Test for Bechdel Tests – a way of telling if your would-be Bechdel Test alternative meets the standards of its namesake.

It was either this or a “Yo dawg, I heard you like Bechdel tests….” meme.

So what have I identified that I’m looking for in a critical tool? It should be short. It should be easy to explain. The individual elements should be uncontroversial to apply to a given work of art. The test itself should have a non-normative thrust. All of that summed up, I give you the Bechdel Test (for Bechdel Test), henceforth known as the BT(BT):

Your think-piece critical test that tries to be like the Bechdel Test is good if:

- It has four or fewer elements

- That are provable in the majority of cases

- Without resort to normative or subjective conclusions.

“But wait”, said the tiny Douglas Hofstadter that lives in my head: what happens if you apply your test to itself? Isn’t your test every bit as subjective as the tests used to criticize it? Again, I have two responses.

First: shut up.

Second: Good point! Sound off in the comments with ways of improving the BT(BT) 2.0!

Had to do it.

Needs more Sexy Lamp Test…

http://endlessrealms.org/2013/03/writing-women-the-sexy-lamp-test/

http://tosche-station.net/cosplay-monday-the-sexy-lamp/

*sigh* Oh, Internet, come on. The Bechdel Test measures for the most simple criterea, but it’s infuriating how many movies don’t pass it so we need to lower the bar some more! Two characters is already too many for most of your favourite movies? Make it just one and throw in something vague like “not defined by” so that you can argue your way out of seeming like an ignorant sexist for liking the film.

The main flaw in reason, imo, is the assumption that the Bechdel Test measures something as vague as “feminism”. It doesn’t. That’s what’s so great about it. It measures literally just if there are meaningful relationships between female characters. If it’s the character arc of a character that we care about, we need a different test. That measures something very specific. Then a few more tests for different elements of the story. And if we put them together, we can start looking for that ever illusive “feminism”.

It’s funny how quickly people get defensive and nervous around gender questions. Sexism isn’t some rare and debilitating state of mind, it’s everywhere and people need to stop being afraid of seeing it.

I’m not sure if the Bechdel Test even measures that, though. One example that really stuck in my head was a movie I saw this past year (and few others did): Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters).

The plot of the movie essentially is that siblings Hansel & Gretel fight a group of about a dozen witches (all female) who want to cast an evil spell. There are scenes when Gretel faces off against the witches and they talk about spells, scenes where the witches talk to one another about spells, scenes where Hansel’s female love-interest talks to Gretel about witches, etc. I was struck by how, after the movie, it passed the Bechtel Test with flying colors, despite not giving any of its characters, male or female, more than the flimsiest bit of characterization.

It struck me as the sort of movie that is superficially feminist (look at all these female characters doing kick-ass things) without actually portraying anything substantive about feminism, gender, etc. The only reason it seemed to pass the Bechtel test was because Hansel was the only male character of note. Perhaps there needs to be some sort of qualifier, that the Bechtel test is only a valid means of measuring relationships of roughly 50% or less of the movie’s characters are female?

Nah, I’m with Ben. The Bechdel test doesn’t need any tweaking or qualifiers. It does exactly what it says it will do. It doesn’t say, “Movies that pass this test are feminist.” It doesn’t say, “Movies that fail this test are sexist.” It doesn’t say, “Movies that pass this test are good and have well-rounded characters.” It just says, “This movie has at least two women who talk to each other in it, and that conversation isn’t about ‘oooh how hot are teh boys.'” It shouldn’t be a hard test to pass, but apparently it is.

As I’ve said before, the Bechdel test is at its best when we look at Hollywood flicks in aggregate. No feminist I’ve ever met would say Casablanca sucks because it doesn’t pass (or that Hansel and Gretel is a great feminist film because it does, for that matter), but lots of feminists will say, “Doesn’t it suck that there are no mainstream movies this summer that pass the test?”

On another note, I’ve always liked the POC version of the Bechdel test, which is exactly the same, except you replace “women” with “non-white people” and “man” with “a white person.” It certainly passes the Bechdel test for Bechdel tests!

I think the problem with “Hansel and Gretel” is that it has the gender-neutral problem of being “Not a very good movie.”

Are the female characters poorly-thought-out sketches of human beings with no internal life and serving only as devices to move the plot forward? Yes. Is that sexist? NO. Becuase so are the male characters! It’s equal-opportunity.

You can have a movie that’s “Not sexist” and is at the same time “Not feminist.”

Agreed. The Bechdel test in neutral and measures a simple of fact of female presence. It does not tell you whether a film is feminist or not because feminism isn’t that simple.

I would still maintain that it measures female relationships, though, as a relationship does not have to be well fleshed out to qualify as a relationship between characters. If two women have more in common than a guy, then they have a relationship.

I think Hansel and Gretel is a good example of why the Bechdel Test can be misleading. But it’s problems are on a level of narration where the Bechdel Test doesn’t even go. Female presence isn’t the issue,the metaphors and themes are. The film is all about the virgin/whore dichotomy. And it’s “feminism” is of the benevolent sexist variety. Only women can have magic in the story. So being a woman carries special moral responsibilites that men do not face? Victim blaming and all sorts of sexual oppression come from this sort of mentality…

Gender studies is a social science/humanities discipline, meaning that numebers can only get you so far. The rest is theory and discourse. Trying to define whether a film is feminist with a simple formula is kind of weird and it trivilizes the problem.

The Mako Mori test is a pretty good litmus test for individual female characters, but it misses the general point of the Bechdel test. It’s all about female presence. Even if every female character in every movie made till now was as awesome as Mako Mori (and I’d never arise that they should be; they should have the same range as male characters) it wouldn’t negate the harmful effects of portraying women as making up a minority of the population.

Recently, a study* of the ratio of male to female characters in movies found that, even in crowd scenes, women made up only 17% of the total. Another study found that, when a group was more than 33% women, men perceived it as being more than 50% women. How movies depict the world has seriously skewed how we actually see the world, so that now we barely notice if, for example, only 17% of CEOs or politicians or professors (or whatever) are women.

Source: http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=197390707

*full disclosure: I can only find references to the study, not the study itself, so grain of salt.

That study you quote is REALLY interesting. I am looking back at my own experience, and I can definiteyl see some truth to it – and how it relates to Hollywood is particularly interesting.

Think of your average romantic comedy, which I’m guessing is usually close to 50-50 men and women in the cast (Male lead, female lead, male foil, female foil). So what do we call the one genre whose conventions pretty much demand something close to parity in casting – a “Chick flick.”

Good find!

I’ll have to see if I can hunt down that study since apparently I enjoy google scholaring things referred to in the press without proper citation.

Actually, the Maoko Mori test would be quite easy to improve.

1. A woman

2. with her own story arc

3. Who is not a love interest or family member to anyone in the male cast.

Because if this version of point three is false, you can bet that her main purpose is to flesh out a male character and his story arc. Also because it seems that of the few women who do appear on film, most do as family members or love interests.

Mim, I like your test a lot, but it needs another name – it doesn’t pass for Mako Mori herself unless adoptive fathers don’t count?

So a mother with a daughter passes but a mother with a son does not? Or a woman whose grandfather appears on screen?

If the grandfater appears on screen, odds are that he isn’t there to fade into the background.

Yeah, I think the family connection thing is a little difficult- that would mean all female characters in movies would have to be orphans with no relatives. Family or lack thereof, is part of the human experience, be it positive or negative. That strips away a fundamental element of being a person from the potential characters; and if the goal is an “objective” way to determine if a female character is being portrayed as a “real” person, stripping that option away limits the possibilities for positive outcomes, i.e. passing the test.

The love interest aspect is a bit easier to accept, but I also think that one could have its proper place, too, but I guess given how *that* is too frequently presented as the main point of a female character’s arc, it makes sense to include not having a love interest in the criteria.

The other two criteria make perfect sense, though- personal story arcs for women in narratives are hard to find.

Men in movies aren’t usually orphans. The point isn’t the connection in itself, it’s that male characters’ families are almost always irrelevant, while female characters are nothing but femily members: the mother, the love interest, the grandmother, the little sister or daughter to be protective of. It actually says bugger all about who she is about a person, while acting as another tool to explore whoever the male relative is.

Is it even possible to pass the Mako-Mori test if the protagonist is male? I suppose you could have a female character whose plotline never interacts with the male’s at all, but doesn’t a supporting character, by definition, support the protagonist’s story, regardless of gender? (Unless you want to define “supports” as a positive support, in which case female antagonists could pass the test)

Yikes. While I really like the article, can OverthinkingIt clean up the editing a bit? Incorrect to/too, and it’s/its, and a weird comma and a period right after.

Agreed!

Since we’re discussing Bechdel-derived tests, I’ll toss Abigail Nussbaum’s Star Trek corollary onto the pile. To pass it:

1) There must be at least two aliens

2) having a conversation

3) about something other than a human, the Federation, or Starfleet.

Source: http://wrongquestions.blogspot.com/2008/01/back-through-wormhole-part-iii.html

Heart.

I know one example of a gender-swapped Bechdel test pass (unless I missed something, which is very possible), Ginger Snaps, and possibly the sequel as well.

Doctor Who: The Impossible Astronaut/Day of the Moon passes the Vito Russo test with flying colors in its use of Canton Everett Delaware.

Although the Vito Russo test has its flaws (as you point out), odds are high that this is exactly the kind of character that the test intends to glorify.

Have you seen Torchwood. Two main characters are bisexual, and they interact about non-sexual stuff all the time.

Perhaps we should have one of those to split up science fiction movies from simple epics who happen to be futuristic… A definite split between Star Wars and Star Trek? lol

Alternative BTfBT:

1) It has four or fewer true/false elements.

2) For any given element’s application to any given work, 95+% of people’s evaluations agree. (Evaluations meet the most typical significance level.)

I’ve been accused of overthinking the test because I try to argue sometimes that a girl doesn’t count, because the original test rules state “two women.” If the movie’s only Bechdel-friendly dialogue is between, say, a female teacher and a female elementary student and it’s brief and plot-irrelevant, I’m not sure it should count. Others disagree.

That’s exactly the sort of thing that makes keeping the test objective more difficult for no good reason. Adding secret subjective conditions like “The conversation is substantive.” blurs the test and thereby diminishes it. Adding arbitrary extra conditions like “The women have reached adulthood.” is pure obfuscation.

Stubbornly twisting the meaning lowers BT’s value. It shouldn’t need to be worded as “Two female-identifying beings consecutively communicate information to each other that does not relate to a male-identifying being.”

For the reverse Bechdel, one that comes to mind is Bridesmaids – I can’t recall if Chris O’Dowd and Jon Hamm ever have a conversation. Another possibility is Matilda – I could see the dad and the brother having a conversation, but the main characters in the movie and book are mostly female.

Matilda easily passes the “reverse” test. The father and son talk a lot, mostly about business.

I think that while the Bechdel Test is not water-tight (Pacific Rim as a film with a positive role model but fails, Transformers The Whatever which succeeds BT but fails the Sexy Lamp Test).

The best part of the BT is that is gets people looking at their work and wondering if they’re lacking anything for a female character to do other than be the aforementioned Sexy Lamp. If they do, but there’s only one (say Avengers, or if a GOOD Fantastic Four movie comes out) then that’s okay as there are mitigating circumstances. Even then you might want to ask yourself, “Why AREN’T there more women in this film?”

Just making us ask and look at the phenomenon is success enough, I feel, and the more public knowledge of it, the more people will be conscious of making better use of women in film.

I do not believe that a Bechdel Test for Bechdel Tests is appropriate. The Bechdel Test is only compelling because of a latent normative sentiment: that if movies consistently are unable to find two female characters to exchange dialogue in a ~2 hour long medium, there is a problem. That is the je ne sais quois of the Bechdel Test. The test is clear and objective, but importantly contains a strong latent normative sentiment, which is not captured by the Bechdel Test for Bechdel Tests.

Take, as an example, the test:

A movies has two characters of six-foot height or taller,

Who have a conversation,

Not about someone who is not of six-foot height or taller.

The test is just as simple and objective as the Bechdel Test, but is not going to become as relevant as the Bechdel Test, because it lacks the same latent normative claim. Portrayal of tall people is not as culturally relevant an issue as portrayal of women. If the test does not capture the strong latent normative claim, then the test is missing half of what makes the test so powerful.

I fear that to make a proper Bechdel Test for Bechdel Tests, there either needs to be an element referring to that latent normative claim, destroying the objectivity of the test, or theoretically, it could contain a similar latent normative claim, though I am not sure what that would look like.

Without reading any other comments…

The Bechdel Test’s objectivity confuses me because I’m not sure how you measure “about a man” in the third point. I know that sounds like I’m trying to pick at the test, but it struck as off a while back when watching “Unforgettable” and then again in “Iron Man 3.”

“Unforgettable” had a female cop talking to a female coroner about a male corpse. “Iron Man 3” has Maya Hansen talking to Pepper Potts about Robert Oppenheimer (or Alan Turing). In both cases they’re technically talking about men so it fails, but in neither case are they discussing a romantic interest or an active character. In “Unforgettable” it’s about a case. In “Iron Man 3” Maya is reflecting how she feels about science-for-war and her work.

I do realize the gross disparity at play, but those instances have left me questioning, at least, my ability to use the Bechdel Test objectively.

While applying the BT is, at it’s root, an objective action, any interpretation of the tests results will always be subjective. We will always be subject to our points of view, passions, life experiences, etc etc etc.