riverrun, past Link and Zelda’s, from Great Sea’s Shore to Zora’s Bay, brings us by a save and continue of revivification back to Hyrule Castle and Environs.

There is a boy. His name is always Link. There is sometimes a princess; her name may or may not be Zelda. There is a villain, who may be named Ganon or Ganondorf; he is sometimes a bandit chieftain, sometimes a giant pig sorceror. Link might progress in a linear chronology, or he might travel through time. He often reaches Death Mountain, though sometimes this is the end of his adventures and sometimes merely a midway point. Sometimes he has a grappling hook; almost always he has bombs and boomerangs. Music is always important.

Which Zelda game am I describing? Potentially any of them (except perhaps Majora’s Mask). Even the ones that are notionally sequels or prequels feature many of the same elements in recognizable arrangements. Link is always defeating Ganon or someone like him, always rescuing Zelda or someone like her. There have been attempts to render Link’s various adventures into a hard chronology and environment, but that’s clearly a retconning, not the original vision of Shigeru Miyamoto over twenty-seven years ago.

It’s not important to the designers that the story of Link and Zelda, when viewed in sequence, make any sort of narrative sense. Rather, it’s important that each individual installment work. When you pick up the controller for Ocarina of Time, you might not know why Link lives in a village of faerie children or who the final villain will turn out to be. But you know that boomerangs paralyze bad guys, that arrows are in limited supply, and that you’ll need to overcome the challenges of a series of dungeons in order to reach the last boss. When Zora or Stalfos or the hand that drops from the ceiling and takes you somewhere show up, you’re meant to slot them into your existing understanding of those characters – even if that understanding is meant to change (Zora is a potential ally this time; Stalfos in Ocarina of Time is a much more heinous and challenging enemy than in the original Legend of Zelda; etc).

And THESE THINGS. Ugh.

In this way, the Legend of Zelda series has something in common with Finnegans Wake, James Joyce’s last and least accessible work. As you may have heard us mention on the podcast once or twice, Finnegans Wake took Joyce seventeen years to write, and he supposedly said that it ought to take a person seventeen years to read it too. It’s known for its cyclical nature, its frequent tangents, and its habit of tossing characters in and out of particular roles interchangeably.

If Finnegans Wake has a protagonist at all, it’s the protean “HCE,” whose initials may stand for “Humphrey Chimpden, Earwicker.” HCE also passes himself off as “Here Comes Everybody” later in the novel. He may be a reincarnation of Finnegan, the man whose wake begins the novel, who is described as a “man of hod, cement, and edifices.” He may also be a reincarnation of Finn MacCool, warrior hero of Celtic myth. These multiple identities are alluded to throughout the text, in tangents and prose poems and made-up words.

HCE has a wife, Anna Livia Plurabelle (ALP), who doesn’t get much chance to speak until the very end of the book. A letter from her becomes instrumental in defending HCE, however, plagued by rumors as he is in Book I of the novel. ALP. may also be the river Liffey, which flows through the center of Dublin. I lay all this out because that’s the kind of book Finnegans Wake is.

There are dozens of other characters who recur and recurve as well, appearing multiple times and in multiple forms, such as HCE and ALP’s children: Shem the Penman, Shaun the Postman, and the girl Issy. Their transformations and translations are as many as HCE and ALP’s, so it won’t serve us to go into overlong detail.

I’m not trying to lay out a point-by-point parallel with Finnegans Wake and the Legend of Zelda, since I don’t think Miyamoto was consciously aping Joyce in the way he structured the games. But a great deal of hard clarity and energy has been put into, if not making sense of Joyce, understanding why he wrote the way he wrote. I think we can borrow some of that same analysis to come at a more interesting understanding of the Zelda series.

This all came to me not because I’m any great shakes as a Joycean scholar, but because of parallels I noticed upon completing Samuel Delaney’s Dhalgren. Like Finnegans Wake, Dhalgren is one of the more challenging novels of the 20th century (when I bought it at Barnes & Noble, the clerk said “good luck”). It’s one of the few science fiction novels that deserves entry, without qualification, into the literary canon. It’s also vastly more subversive than I would typically associate with science fiction, a genre that struggles at times to move through its jetpack-and-raygun days.

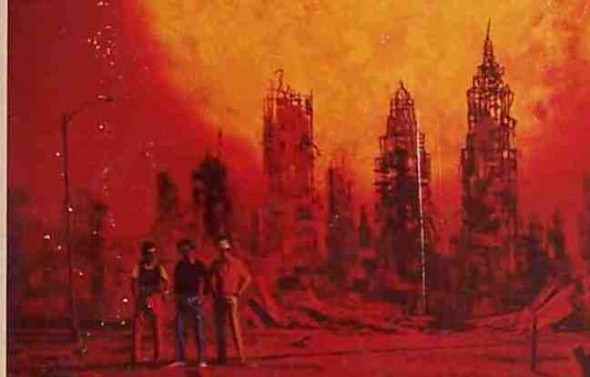

Dhalgren is one of those novels that doesn’t give you much of a hook for what it’s “about” (so feel free to lose interest at this point). It follows the travails of an unnamed narrator, referred to at various points as “the kid” or “Kidd,” through the city of Bellona at the center of the United States. Some unspecified cataclysm has struck Bellona and conventional law and order have been abandoned. But people still live there and still flock there, as the kid (Kidd) does. Packs of armed marauders, cloaked in giant animal holographs, roam the streets, along with itinerant preachers, freelance journalists, experimenting hippies, and misplaced bohemians.

The kid stumbles into this microcosm for reasons that are never clear. He discovers two useful tools shortly after entering the city. The first is a trio of blades meant to be mounted on the back of the hand, an orchid, tossed to him by a stranger whom he passes on the way into Bellona. The second: a notebook with half the pages already filled. He starts writing his own poetry, drifting from one faction to the next. In the process, he discovers that a myth of sorts is building around him, partly inspired by daring actions he takes within the city, partly inspired by things the kid doesn’t remember at all.

Dhalgren is about many things, but high on the list is the notion that identity – I am; it is – is not a fixed property. The legend of the kid grows without any conscious effort on his part to build it, until he finds himself a reputed figure, much to his own confusion. The kid himself is an ambivalent bisexual, and of a vague enough ethnic background that none of the city’s enclaves know whether to claim him. The city of Bellona means different things to everyone who lives there – the gangers, the love children, the poor black community, the drop-outs, the misfits. The city literally changes without warning: duplicate moons appear in the sky; buildings burn incessantly without deteriorating, then vanish overnight.

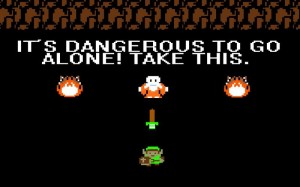

I was first drawn to the parallel between Dhalgren and The Legend of Zelda by the orchid. Without spoiling the novel – can you spoil a non-linear book that defies narrative conventions? – the orchid becomes especially significant toward the end. It’s a weapon, yes, but it’s also a gift: a bit of generosity from one stranger to another. With it, the kid is defended, but he’s also very much armed. He enters every situation with a bladed gauntlet dangling from his belt, a circumstance that occasionally gets him in trouble.

Dhalgren is a consciously Joycean novel, which inspired me to look a little further. Just as the kid is a person of no fixed identity – a vagabond, a lover, a hero, a poet; someone who can barely recognize the stories being told about him – so too is HCE a figure of multiple dimensions. He is both a person and a sentiment (“Here Comes Everybody”) and a place (“Howth Castle and Environs”) and a giant out of legend (the titular Finnegan). He is a monomyth – a neologism that Joyce invented in Finnegans Wake – a man both real and legendary, a man with no fixed identity but whose exploits are patterned.

Could the same not be said of Link? Most of the Zelda games take place in very open worlds, with adventures both mundane and epic. What would Hyrulean storytellers a generation hence say of Link? Oh, yes, he’s the young man who saved the princess from Ganon with his bow and magic sword. No, he wasn’t a young man; he was a kid. It wasn’t a bow he wielded; it was an enchanted mask. Also, he had an ocarina, and he used it to summon the wind. No, Link’s that asshole who smashed all my pots.

The point of this exercise isn’t to assert that Miyamoto had a particular fascination with James Joyce. That’s the sort of assertion that can be easily proven or disproven by consulting the historical record or finding the right interviewer. Interpreting any work of pop culture through a particular lens does not presume authorial intent (we say this a lot; it’s worth repeating). You can read the works of Coleridge with a Marxist interpretation, even though Coleridge’s corpus predates Marx’s by several years. Rather, to interpret one work through a particular philosophy or authorial viewpoint is to say, “Insofar as this philosophy or author says true things about the world as we find it, those true interpretations may also be applied to this work, regardless of the latter author’s awareness of that philosophy.”

What, then, do we gain by viewing the Legend of Zelda through a Joycean lens? For one thing, we are freed of the burden of continuity. Let the scope and direction of Link’s adventures change drastically from installment to installment. So long as he’s got a hookshot and some rupees, it’s the same guy.

So the story of the Legend of Zelda, then, is the story not of Link, or Zelda, or Ganon, but of Hyrule, a land that generates adventures and summons up adventurers, like leaves drifting off of it, yes, there’s where, the rupees insideish the tallish grassish, where Navi calls, coming, far, end here, off track, Link back, to continue to save, a shield a sword a link a long the

Your second paragraph gave me BioShock Infinite willies. That my mind leaps to that particular reference suggests I should read more.

Also, did your first paragraph get cut off, or is that a Finnegans Wake reference?

Finnegans Wake both starts and ends in the middle of a sentence, like this article.

It actually starts and ends in the middle of the same sentence as the article does, pretty much. Which means that you could read Finnegan’s Wake cover to cover, then jump to the beginning of this article, read through to the end, and then loop back to the beginning of Finnegan’s Wake. I’m gonna go out on a limb here, and suggest that this was Joyce’s original intention all along.

Although interesting, this article seems to be much more about Finnegans Wake and Dhalgren then it is about Zelda. It certainly spends much more time describing those stories and their connections to each other than it does on Zelda or either story’s connection to it.

Further, I find the link to Zelda to be fairly weak. From what I understood, the core message as it relates to Zelda seems to be that there are certain key elements that define games in the series, and that the story continuity is less important than those elements. But that can apply to just about any long-running video game series, or really any long-running series in general (but the length of time needed is compressed for games due to the very rapid evolution of the medium).

Without these elements, it wouldn’t really be a Zelda game at all. They are what defines the games, much more than any story. But looking at other games from Nintendo that have existed over the same time period, they have undergone much the same sort of changes as Zelda has. The Metroid series is a prime example (pun intended), but the Mario games, although not even pretending to have a story not to mention a continuity, still maintain certain core elements in the face of massive changes in both technology and expectations. Attempts to substantially deviate from this set of core principles have been one-offs that have generally not been considered “true” members of the series.

This is a fair cop, although I think I’m safe in presuming the audience has more familiarity with the Zelda series than with Finnegans Wake or Dhalgren. But, still, it’s incumbent on me to make this sort of thing clear.

I think Zelda is an analogous case, in a way that other games aren’t, because the characters are the same between most of the games. The Final Fantasy series, for instance, has zero overlap between titles (aside from chocobos and airships). The Final Fantasy franchise means a certain atmosphere and tone, but not a universal setting or characters. Dragon Quest, conversely, has a pretty explicit continuity, at least between the first four entries in the series. So those lie at opposite ends of the spectrum.

The Zelda series, on the other hand, occupies a weird space: same characters, same setting, yet almost completely different every time. The best analogy is a story that is thousands of years old, undergoing major revisions every few generations due to the inherent lossiness of oral tradition.

I get what you’re saying about the Mario series, and I kinda see it. The Mario games have always felt more contiguous to me, though. There’s a sense of the big bad guy (Bowser) kidnapping the princess again, and Mario adventuring through a gauntlet of demon-infested worlds again. Each Zelda entry, on the other hand, seems to present the characters afresh.

This probably has a lot to do with the fact that Zelda, unlike most Mario titles, always has an rpg, character-building element. Link always needs to go from three heart containers up to the max of twenty, or whatever, and collect all of the gizmos. But Mario, at the end of any given game, has no skills or possessions that he won’t have at the beginning of the next game.

And once they got to the point of having plots and whatnot, the Zelda franchise did the same thing with narrative elements. In most of these games, there’s a point where Link *meets* Zelda, and learns about the nature of the Triforce, and so on, always as if this was the first time any of this had occurred.

But with the Zelda games they aren’t the same characters. Each Zelda game has an entire new set of characters. Pretty much only Ganon/Ganondorph, Vaati, and Twinrova make true repeat appearances. But each Link is a different young character who happens to wears green clothes (with the notable exceptions of Majora’s Mask and the Oracle games). Each Zelda is a different princess (or not even a princess at all). Each Impa is a different servant of of this different Zelda. The Gerudo and Zora are different not because the story is told differently, but because they are either entirely different races or at least a races that have gone massive changes over hundreds or even thousands of years.

The story battle over the triforce is told differently each time because each time it is telling the story about a different battle at a different point in Hyrule’s history. The events of Ocarina of Time are explicitly described as an ancient legend known by the characters in both A Link to the Past and The Wind Waker. By the time of Link to the Past, the Hylians of Ocarina of Time no longer exist (having developed into Hyrulians), and their language can only be translated with an obscure book.

In this way it is more like the Breath of Fire games, where each game features characters with the same name and some shared characteristics, but each is a distinct individual who simply, by coincidence, happens to have those characteristics. It may be considered a matter of fate, that a Link and a Zelda are born whenever Hyrule faces a threat.

I would also say it is kind of like the Metroid games in reverse. In the Metroid games, the main character, Samus, is the same throughout the series. Each story has many elements that are similar, the settings, many of the weapons, mother brain, kraid, ridley, and the titular metroid. But, except for a few areas in Metroid/Zero Mission and Super, they are not the same. Norfair in Super and Magmoor in Prime are on totally different planets. Ridley and the metroids are killed and cloned again and again. Mother brain and Kraid are killed and cloned once each at least that we know of. The plasma beam in Prime and Super have pretty much nothing in common besides their name and their destructive ability.

So overall I don’t think the connection you are positing here fits. It is not that the stories are different in these games because they are being told by different people, the stories are different because they are describing different events and individuals.

I also initially thought you could make the same case for Mario, but then thinking more about it I see that, while there are some common elements in some Mario games, the actual character of Mario is much more concrete and continuous, so that it’s easier to see Mario as always being the same Mario, more in line with a character like Mickey Mouse.

That’s because we have numerous instances of Mario not in ‘Mario games’, e.g., Dr. Mario, Mario Golf, Mario Kart, Mario Tennis, etc. Perich’s Joycean lens kind of helps explain why we never see Link in similar roles, because it would feel somehow wrong to see him swinging a golf club or racing a kart if it’s not part of some larger quest. The only exception I can think of is Super Smash Bros., and even there it more feels like we’ve got the archetypal Link that’s been unwillingly pulled into this new battle space, as opposed to a separate instance of the character.

To draw in some identity theory here, one could say that Link’s identity is dependent on whatever is most salient, given the specific, momentary context, both within each individual game, and overall in the entire canon. Salient to him because of what he accepts as his duty/what he does; salient to the player because of what they interpret as most importent as they play or recollect the series. Link in-game may think of himself as a warrior, but the person playing him may think of him as a kid. Or vice-versa. And the same player may change their interpretation in a given context- one game, they see him as the warrior, in another, as a child caught up in the whole thing. As would Link in-game. Link means different things to different people in different contexts, irrespective of what he may think he “is,” what he’d claim to be his own identity.

And I think you’re saying this can also be applied to other story elements, such as characters, specific locations within Hyrule, and objects. Which I actually think is slightly more interesting than focusing on Link himself. If you draw back and consider things in categories or nameless groups, baddies, goodies, stuff, places, then different combinations of different variants of these things all add up to whichever game- or moment in-game- is under scrutiny. And what’s kind of neat is that a person’s answer to, say, the question of, “What’s Link’s main weapon?” may say more about the person answering than Link or the series itself.

I think that’s a very interesting element that you’ve raised– maybe something that the writers at overthinkingit would care to explore in more detail?

Your point does sort of force me to realize that every time i’ve played a Zelda game, I’ve read the opening story, the establishment of the mythos and setting, with sort of my generic internal ‘wise old seer’ voice, while in fact the voices could be as varied as the games themselves and could have deep implications in relation to the privileged ‘objective’ perspective which I had believed myself to have.

So one of the things that can be both liberating and frustrating about extreme critical theory is the notion that everything is subjective- everything. Even that notion itself- subjectivity is itself subjective (recursive argument is recursive, eh?). It comes in handy for critical theorists when they’re tearing another theory apart (because if nothing else, they can throw an argument that essentially boils down to, “Well, that’s what you think!” out) and (at least I think- subjectively!) can get abused as a cop-out sometimes. But it does have a lot of value (in my opinion, granted) when considering the experiences we have as persons, humans, animals in the ecosystem, and individuals in what is, whether we like it or not, a collective that in itself is much like an ecosystem in that various parts of it are contingent and dependent on others (i.e. society). If we consider experiences as subjectively relational, whether in relation to someone else, something else, or even our own inner selves and multiple identities, then it makes sense that we’d feel like or see things as a different person in a given moment.

So yeah, if you apply this to individual experience and how we perceive things, it follows we may assign meanings and labels to things and persons irrispective of their meaning assigned by others (or their own selves), because we cling to things we cling to, and what resonates with us is what helps us assign meaning in the first place.

And that, I think (suuuubjectively!) is the basis of a lot of disagreements. Two people may “see” the same thing in completely different ways because their personal experiences have shaped the way they perceive that thing in that given moment.

Granted, it can get exhausting (and friggin’ time consuming) to step back every other minute to contemplate who I am, where I am, what I am, etc., and how all those axes interact with each other, but it does help when having discussions with other people- it makes understanding (even if not agreeing with) differing perspectives much easier, and helps keep the idea that there’s a “right” and “wrong” in a given situation at bay. Especially on the internet. Because too frequently, Duty Calls: http://xkcd.com/386/

End babble session.

I agree with you! Of course… what does that really mean?!

Interesting article. The community that organizes Zelda continuity always struck me as odd. The games never suggested a linear history to me.

If I may:

http://baconthorpe.wordpress.com/2013/08/10/the-legend-of-zelda-phantom-continuity/

The chief problem with Zelda has always been the pure laziness with regards to the narrative since they ALWAYS just seem to redo the original with increasingly lamer McGuffins and Gannon becoming lamer and lamer with each incarnation.

There is ZERO reason to get attached to anything in the game because nothing changes, except for the art style. WORSE is that the weakest narrative-wise game (Link to the Past) is what they base all of the re-tred material off of and let’s face it, Link to the Past scorched earth the mystery of the environment and characters/concepts to the point of making them banal and boring. Gannon’s a thief and the TriForce are now just generic “Golden Power” that you don’t even fight after; you go after princesses and pendents and musical instruments and other lame mcguffins.