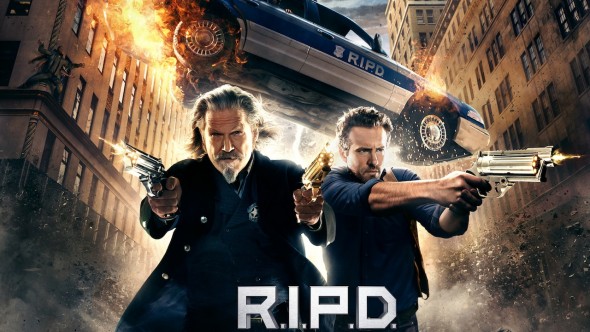

We’re just fascinated with this movie. We can’t help it, OK?

Perich

I was reading some Reddit reactions to R.I.P.D. this morning and found one comment where someone complained about the movie setting up “in-universe rules” and later ignoring them.

I haven’t seen R.I.P.D., so I don’t know if this is a Chekov’s gun complaint. But based on other comments I’ve seen lately in other contexts, I suspect it’s not. I suspect rule-adherence is valuable in and of itself.

There seems to be a decent subsection of fans of genre films and genre books who think that the “rules” under which magic or fictional technology operate are an important artistic consideration. If a setting has innovative rules for magic, that is noteworthy. If a story establishes the rules of magic and then breaks them, that’s bad.

As a critic, connoisseur, and erstwhile artist myself, I don’t understand this aesthetic. For me, what makes a movie or book good are considerations like plot, characters, imagery, tension, tone, etc. The idea of keeping score with some eye toward perfect consistency is alien to me. In fact, some of my favorite films fail this benchmark without losing any points in my eyes (e.g., in Casablanca, once Major Strasser’s been shot, can’t all three of them get on that plane?)

To use the example we always return to: in A New Hope, the rules of The Force are never clearly established. Apparently, The Force can mimic giant animal noises, hypnotize people, let you see in the dark, choke people at a distance, preserve your spirit as a Force ghost, and aid in missile targeting. Nowhere is this laid out. Yet I would never say the movie suffers for it.

So whence this fascination with the rules? And what do the people who like rules get out of it?

Fenzel

This is an interesting question, and I think there are a host of reasons why people get upset when sci-fi / fantasy rules are broken.

Some of it is emotionally unhealthy. People who get in cycles of anger, don’t spend enough time outside of fantasy universes and are looking for reasons to be upset. But I’ll put that aside for a moment.

I do think it tends to sap a lot of dramatic tension. It can demonstrate that the filmmakers have failed to set up what is at stake and what obstacles characters need to overcome to get there. This is especially true when a constraint seems really difficult to accommodate within your genre, so people expect to be surprised by how it’s dealt with (Revolution is a good example of this – people wanted to see how the show dealt with its constraints, and then it just didn’t).

Related are instances where the rules set up guard rails for the story, forcing the characters to do the fun things in the movie rather than much more obvious things that nobody wants to watch. When those rules are broken, it raises the question of the characters aren’t doing the obvious thing, which the filmmakers had hoped to dispel at the beginning of the movie.

Guard rails, Marty!

Another good example of both of these is the 1.21 jigowatts and 88 miles an hour rule in the Back to the Future movies. They set up challenges for Marty and Doc to accomplish, and they prevent them from just using the time machine whenever they get in trouble. Mister Fusion lifts one of those restrictions so the movies aren’t too repetitive, but they keep the other one. If they got rid of it, it would be shitty.

Others work as jokes or stunts, where the only reason the rule is even mentioned is foreshadowing something that will happen later. You make a mental note to look out for that thing and if it never shows up or shows up but drops the ball, it’s disappointing.

A good example of this is crossing the streams in Ghostbusters. It’s mentioned early on that crossing the streams is really bad and if anyone does it, something terrible will happen. Later, they disregard this and cross the streams anyway, but the characters acknowledge the previous rule, and the scene where they cross the streams is awesome, so we’re not disappointed. It’s not about getting it right; it’s providing a payout like you promised.

The trick with that is when the filmmakers think they are providing an awesome payoff of foreshadowing, but really they’re just doing bullshit. Indiana Jones finding the Crystal Skull aliens and they do crazy light show stuff and then just leave is a good example of this.

It’s easy to point out that the scene makes no sense based on what has been established about these aliens and how there’s like mind control powers involved and global domination or whatever. But the real problem is the whole sequence is terrible for plot, story, character, pure awesomeness–basically every conceivable reason. We complain about the violation of the movie’s own principles, but we’re saddened and upset by the violation of the movie’s own expectations.

Midichlorians are like this. They’re a setup with no payoff. The Force didn’t need them because The Force was already providing great payoff scenes based on the vague expectations it had already established.

At the end of the day, it’s not that different from anything else set up about a character. If there’s going to be a big twist, and the teacher is going to turn out to be a stalker/murderer, the characters are writing better do it credibly, and it really helps if the reveal itself is awesome.

It’s also an element of production value. Shoddy adherence to your own universe’s rules can be seen as a sign of laziness or lack of focus and attention to detail.

A good example of this is in Star Trek: First Contact, when at the end of the movie Worf says the Vulcans didn’t detect the Enterprise because they were masked by the moon’s gravity. That’s nonsense and not consistent with how the Star Trek universe works, but it mostly just feels lazy and sloppy and isn’t a big reason to be upset.

“It’s deliberately sloppy.”

Doctor Who gets away with a lot of rule breaking, because it had been established that its production is deliberately sloppy, and it’s justified by the characters and makes sense for the story. Plus, the payoffs are usually awesome even when they are dumb and make no sense. But when they fail to deliver an end-of-episode or end-of-arc payoff, all of a sudden the shortcomings of the sci-fi world-building they’ve done feel much more glaring and obvious.

“One of the most powerfully overthinkable moments in the last 20 years of film”

Ultimately, it’s about whether the story is satisfying or not. I feel compelled to return to one of the most powerfully overthinkable moments in the last 20 years of film, when the tears of Pikachu restore Ash Ketchum to life after he is turned to stone in Pokemon: The First Movie. As far as I know, this happens for no reason. But the story of Mewtwo is all about the pain of isolation and the indignity of being used by people, so the Lazarean tears of Pikachu, the ever-loving, ever-loveable friend-not-servant work to tie the movie together, despite making no goddamn sense.

Adams

I fully admit I sometimes have the same complaint about movies that forget their own in-universe rules – and I say “forget” because violations of the rules, on the other hand, are sometimes OK. As Pete mentions above, we don’t mind when the Ghostbusters cross the streams or when Harry Potter survives the Avada Kavadra curse, because there are good story-centered reasons for the violations, and the “rules” are at least acknowledged.

“Probable impossibility is preferable to an improbable possibility.”

I think the complaint with in-universe rules being broken is that it takes you out of the action. For a certain type of person, we pay a lot of attention when the world-building/rule listing is going on. And when those rules get broken, it’s jarring. Your suspension of disbelief is hard-won, and all of a sudden you’re wrenched back into reality. It’s Aristotle’s whole “probable impossibility is preferable to an improbable possibility.”

There’s also the matter of stakes. We accept that Wizards exist in Harry Potter, and we accept that they can do fix all sorts of problems that would be hopeless in our own world – but because there are limits on what they can do, you still have conflict. Voldemort is THERE and we can’t get there because of the rules of magic, so we will need to do X and Y clever things to get around it.” If the rules aren’t really rules, though, then it’s hard to keep the feeling of conflict/stakes alive.

That said, there is definitely a current of “poking-holes-for-the-sake-of-poking-holes” that runs through a lot of those criticisms – it’s fun to feel smarter/holier-than-thou by poking holes in the rules of the universe.

Fenzel

Fictionally, plot-hole poking probably serves a similar purpose to gossip – you talk with your friends about the things other people do wrong to fill a need to understand rules in a way that validates your own preferred behavior.

If two friends of yours are sleeping together secretly, does it really matter to you? Probably not. But you might still talk about it because it is satisfying and exciting to do so – and it’s satisfying and exciting to do that because social groups or organisms that self-police behavior socially are advantaged in the struggle for survival.

Mlawski

I had an overlong sociological answer, which I’ll boil down to

a) it’s the rise of geek culture and

b) the rise of the knowledge economy (related).

“The geek with the most knowledge has the most power.”

Basically, geeks like memorizing intricate (crunchy) rule systems and engaging in rules-lawyering. It’s a power thing. The geek with the most knowledge has the most power. (See: Comic Book Guy stereotype.) Also it can be fun. Geeks are the new pop culture critics, because they run the Internet and no one reads newspaper critics anymore.

These points fit in with the larger trend of gamification in society. There’s this idea nowadays that life should be a mathematical equation: plug in knowledge of scientific/economic/pickup artist rules + use knowledge well => money, sex, and power. Or, for religious fundamentalists: knowledge of the rules + following the rules => Heaven. So in the movies, rules/mythology must be clear and constant, and the characters must use the rules intelligently. Those who don’t are “too dumb to live.” Movies that operate in a more surreal/pomo/random universe are not for geeks and therefore are relegated to indie-land.

Big exceptions:

1) Like Pete, I thought of Doctor Who. It kind of wrecks my whole argument. I think Who gets away with its rule-flouting because of nostalgia and because it has such an extensive mythology. That gives the uber-geeks a different way to exclude people deemed not knowledgeable enough: “Ugh, I bet you just like the new Who. You probably can’t even name all the companions between 1970 and 1975.”

2) Game of Thrones has ushered in a trend of fantasy that is less rules-based. This kind of fantasy is allowed when it is violent and gritty. As a member of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, I’ve noticed many fans and some creators have this idea that rules = logic = SFF “hardness” = male = better, while fewer rules or rule-breaking = emotionalism = “softness” = girly = gross. Thus rule-bending is only allowed if it is balanced out with decapitations, zombies, and rape scenes.

(I’m probably being really unfair to geeks right now, so here’s a disclaimer: I am a geek, most of my friends are geeks, I was just at a geek convention and everyone was really nice there, and I’m going out tonight to play Carcassonne and Settlers of Catan. Ni!)

I feel we should also note that while this is a growing trend in modern pop culture, it’s not completely new. Back in the 19th century there was a lot of discussion about rules or the lack thereof in Gothic horror and detective stories. If I’m remembering my Gothic fiction class in college correctly, readers tended to prefer the rules-based stuff. In my opinion, those stories were a lot less interesting and scary than the ones that broke their rules or never had rules to begin with.

Fenzel

In it for the LORE.

I’d say under this discussion, “lore” is similar to “rules” in bringing pleasure to systematic thinkers. Game of Thrones has lots of people, myself included, who derive joy from absorbing and processing all the ancillary information. And I think many people still expect that at some point the rules of the universe in Game of Thrones will be explained – though personally I’d very against that happening.

And while this definitely explains some of the cultural fixation on rules in existing movies – even more than that it prompts people to make movies and other art with more elaborate rulesets to begin with – and while the satisfying or unsatisfying payoff of these rules is still anchored in the story, the amount of time and effort invested :/ then in the first place shouldn’t be discounted.

Although I wouldn’t limit the phenomenon to geek culture, either. I recently watched the pilot for Airwolf, the classic 80s super-helicopter show, and was really surprised by the amount of time and effort put into describing the technology and capabilities of the helicopter – even more time than was spent playing cello on a lake for bald eagles. It’s a late Cold War thing that’s all over Tom Clancy books too–people totally geeking out about the arms race.

And I think people similarly have done it historically about cars and guns and all sorts of other stuff too. But the fixation on doing it about universes that are entirely imaginary with no basis in reality is what I’d generally think of as the rising Geek Culture trend.

Perich

Can you guys give me an example of where breaking the rules has taken you out of the story? (I don’t doubt this; I’m just curious)

I can give a few examples of works where adherence to the rules–or even a stringent acknowledgment of them–has taken me out of the story:

(1) There’s a well-regarded fantasy novel by Lois McMaster Bujold, The Curse of Chalion, where the protagonist falls victim to a curse. A little after this happens, there’s a chapter where he and some friends talk about the “rules” of the curse and whether certain actions will or won’t bring down doom upon the protagonist. To me, this is awful. Treating a curse like a footnote in a legal opinion, as opposed to a bizarre and unnatural terror, saps the tension out of the plot for me.

(2) The Jim Carrey theological romance, Bruce Almighty, made a lot of hash over what the few limits were on Carrey’s unlimited power. Every time these rules were referenced in the script, it threw sand in my face.

Lee

The most recent egregious example of this that comes to mind is Prometheus. (Spoiler alert)

This chart perfectly illustrates the lack of logical flow to the escalating events in this movie.

In a different movie, could the same plot points be used to tell a much more compelling story? I don’t think so. In other instances, I could totally see how a story with logical gaps or internal inconsistencies would fail in the hands of a lesser director (Christopher Nolan’s movies come to mind), but Prometheus is not one of those movies.

Still bitter about this one, in case you couldn’t tell.

Fenzel

(Prometheus spoilers)

Prometheus could have gotten away with more if the space jockeys had talked more and/or had characters we cared about. Then there would be more tension in their conflict with humans. As it was, there was mystery, but not tension.

Also “this is where the alien from Alien came from” is not a sufficiently big reveal to satisfy the setups in the movie. We all already know that the xenomorph is going to show up at some point. Prometheus has buckets and buckets and bathtubs full of windup that makes little to no sense. The black goo is a non-character with no lines that still manages to be the main antagonist. It needs to have something HUGE at the end to justify its use of everyone’s time and to make the nonsense worth it. It really doesn’t.

It’s a lot like Revenge of the Sith. We all know Darth Vader is coming at some point, but by the time we get there, who gives a crap?

Belinkie

Not sure it’s exactly the same thing, but I soured on Looper because I feel like it didn’t want to play by its own rules. It started off with the promise of being a logical puzzle to solve and ended up very new age-y and not really about time travel that much.

Fenzel

(Looper spoilers. Be warned.)

Looper is such a friggin’ cop-out. A lot of bad things happen in a lot of movies. And sure, a lot of those bad things would end for the characters in the movie if they just killed themselves. If Bruce Wayne killed himself as a child, there’s no Joker, and few if any of the bad events of the Batman movie ever happen. If Jeff Goldblum in Independence Day didn’t want to be humiliated by his estranged wife hanging out with the president anymore, he could just kill himself. Everyone else on Earth is dying, so it’s not like he’d miss anything. Problem solved!

The guy in Looper could end the events of the movie at any point by killing himself. But of course he doesn’t want to die–but doesn’t quite live, either–which is what the damn movie is about in the first place.

If the loopers are okay with dying when their loops are closed, nothing in the movie matters. That’s why the scene of the guy being dismembered is so dramatically intense. Why doesn’t he just keep a cyanide pill on hand and take it as soon as the message appears on his arm? Because he doesn’t want to die!

“Hey, I know how I’ll stop Jason! I’ll chop my own arm off with a machete and bleed out so he won’t want to be in the movie anymore!”

As we’ve said, movies that require people to do unlikely things that we want to watch rather than obvious things we don’t want to watch sometimes require guard rails, perhaps in the form of technology or magic (“Doctor Octopus can’t be reasoned with or paid off, he’s under mind control!!”). But some of them are much more basic. The most basic I’ve is characters are generally not allowed to say “Fuck this movie, I’m not a real person with a self-preservation instinct or a subjective experience of reality. I’m just words on a page or lights on a screen, so I’ll just kill myself.”

Looper sets up this survival story about a guy metaphorically trying to evade his own inevitable death, despite the fact that he’s an unhappy and amoral hedonist. He meets these people he really likes and realizes things in life matter, and that he’s caught in this psychological cycle of abuse and he decides to make a difference. Great.

You know what your therapist would never tell you to do when you’re talking about trauma? Kill yourself to spare others the inconvenience of your existence.

For him to but only do that, but to be so cavalier about it when it happens? It’s a betrayal of the most basic premise in the movie – of any movie. Which is that pictures of people on screen are pretending to be actual people.

I’d say that’s another way rules in sci-fi and fantasy can disappoint you: when they serve as metaphors for something in a very specific way, and then they diverge really sharply from the material they represent. Because the vehicle is usually set up to match up plausibly with the tenor of the metaphor, divergence from the rules of the thing the movie represents usually shows up as divergence from the internal rules of the movie as well.

A good example of this is when Jessica Alba has to stand in the middle of the bridge in her underwear in the Fantastic Four movie. “The Invisible Woman” is a weighty title that conjures a feminist critique of the lack of credit women historically got for their work as scientists, colleagues and collaborators of professional men and mangers of homes. That her powers would make her into PG-13 cheesecake is way, way off from what she represents. So it also feels really implausible for the situation and takes you out of the movie entirely, as it’s painfully obvious the real-world filmmakers just wanted to show Jessica Alba in her bra and panties.

This is all a bit off topic, but seriously, the end of Looper sucks.

Also, I never realized that about Casablanca. Man, that’s bullshit.

“Here’s looking at your plotholes, kid.”

Perich

1. I think I get what you’re saying about Looper, but I disagree that it’s a copout. I think it’s actually the point.

2. There are probably all sorts of real reasons why only two people can get on the plane in Casablanca. There’s probably a customs office in Lisbon that would put Rick back on the plane. Or Captain Renault would probably call the Luftwaffe if Rick didn’t keep a gun on him.

The point is, the movie sets up several obstacles: the letters of transit, Major Strasser, Rick’s feelings for Ilsa. Realistically, removing any one of them should be sufficient to get the good guys out of Casablanca, but it wouldn’t be a very satisfying movie if we left the other two unresolved.

Stokes

At its worst, rule-breaking creates plot holes, which, like any other plot hole, can range from “ruined the film” to “oh, who the eff cares?”

In general, I feel like “soft”/vague mythologies are less vulnerable to this… unless you make the rules clear, how does anyone know that you’re breaking them? What seems to provoke the nerdrage is sci-fi that aims for hardness and misses.

Pete, are you really complaining about Looper? Or are you just complaining about suicide qua suicide?

Belinkie

Pete, you’re not actually suggesting that no character can change and decide to make a noble Tale of Two Cities style sacrifice, right?

Fenzel

Sadly, I have to say I’ve never read A Tale of Two Cities. As for my problems with Looper, they’re probably have more to do with my problems with cultural ideas of suicide than just my problem with just the movie. I tend to view suicide, barring stuff that would be end-of-life anyway, as a public and mental health issue, and I tend to think stuff that romanticizes it as a rational choice misrepresents what it is in reality.

Of course, there are all sorts of self-sacrifices in stories (like The Core / Armageddon/ Vegeta vs. Majin Buu) that I don’t intellectually or emotionally connect with real-life suicide. I tend to draw a line between suicide as someone might do for everyday reasons versus working a double shift at Fukushima.

I use any excuse possible to put this image into posts. – Lee

Take Terminator 2 for example. If the T-800 were a person instead of a robot and still killed himself, that ending would probably upset me, and I’d probably get in a bunch of arguments about it. Because people generally really don’t want to die, people dying when they don’t have to isn’t a cool thing, and vulnerable people shouldn’t have a bunch of rosy images of the benefits of offing yourself put in front of their faces by our culture.

So, with all that in mind, I’ll draw the line on suicide in a movie earlier than most people.

But there are still cases when I think it’s a cop-out, where people who would very much like to stay alive kill themselves or have an implausibly casual attitude toward themselves dying just so the story can be over quickly.

I see Looper on the wrong side of this divide and would have preferred the main character take less of an easy way out. But as riled up as I get about that, I don’t think it ruins the movie. It just makes it less than what I wanted it to be.

Stokes

What makes Armageddon different from Looper, I think, is that the former is a Utilitarian Nightmare World Dilemma. Either you or your son in law had to die saving the world. Which death, in the long run, will maximize Liv Tyler’s happiness? Choose!

Looper is a different and more sinister beast. For although there is a proximate emergency that Bruceph Gordon Willet’s death is meant to hold off, there’s also a percolating sense that the real reason he needs to kill himself is just that he’s a toxic person who makes the world worse by being around.

Fenzel

Right. And I don’t think he was really that toxic a person. At least not hopelessly so.

Adams

I agree with Stokes that world-building errors are not fundamentally different from other kinds of plot holes, though I think as a general rule they tend to be more glaring in that they’re “unforced errors.” If you’re already bending the laws of the universe to suit your story, and if you’re going to take the time in the script to provide exposition about what those rules are, the least you can do is make sure that you follow those rules.

“I spent the rest of the movie just being annoyed at the inconsistent time-travel logic.”

The most glaring example of a time where I was completely taken out of a story by a internal-consistency error was in Butterfly Effect. There are all sorts of problems with it, but the one that sticks out is the scene where the main character is in prison, and to prove to his new cellmate that he really has time-travel powers, he goes back in time to when he was a kid and slams his hands down on some nails so that he’ll have scars. But this goes against the ENTIRE POINT of the rest of the movie, which is that even small changes will effect the outcome of his life. And it doesn’t make sense anyway – if he had already scarred himself, the inmate he’s talking to would have never known him without scars. When that part hit, I spent the rest of the movie just being annoyed at the inconsistent time-travel logic.

I guess my point is that when you have a rule-setting monologue at the beginning of the movie, I’m primed to pay special attention to those rules. When I watch a movie like Inception, part of the fun of the movie is grinding my gears keeping up with it.

Of course, some internal rule breaking is fine, either because it’s justified by the plot or its so minor as to not be a big deal. But I’m much more upset when the Wizard does something that the monologue about magic at the beginning of the movie said was impossible than I am when some wider rule of science or physics gets broken.

Wrather

As interesting as these digressions are, and as interesting as the typology of rulesets in SFF world building is (mmmm!love me some typologies!), I think we’re begging the question here.

When our complaints imply that art’s most important duty is internal consistency, I think we reveal an impoverished sense of what art is and what it’s for. Dramaturgically, we’ve moved beyond the classical unities, and while I think it’s important for a work of art to have something like integrity (imagine drawing a stick figure in crayon on top of a Rothko — the two things just don’t fit together), I think that we push that demand too far when we insist works of generic art resolve like something from the Dell Book of Logic Problems.

“I think that we push that demand too far when we insist works of generic art resolve like something from the Dell Book of Logic Problems.”

I understand the wish that the characters and incidents in our stories behave in predictable ways. I think it’s related to the childlike wish that the world make sense, that it conform to our innate sense of cause and effect or to the ideas of justice we develop very early in our lives. I think it’s not merely coincidental that this fanaticism for rule-following comes at a time where we spend more time each day (and are more comfortable) interacting with machines than with humans, which is a relatively recent development in our history.

Great art is surprising and strange and full of mystery. Rule following comes below several things on the list.

But there’s another level, a personal edge to a lot of these kinds of complaints. (And, following Pete, I’m skipping over the unhealthy tendency to entertain ourselves online and off with our own capacity for feeling aggrieved; and I’m going to skip over the phenomenon Mlawski highlights of the ascendency of the “geek” culture, though I think it’s troubling and worth examining in more detail, because it involves the transformation of a maligned outcast subculture into a hegemonic discourse which has become oppressive on certain message boards.)

I think the personal edge has to do with feeling taken for a ride — feeling lied to or used. The corporations behind movies and TV want that geek money, and promise that they love you and will be there in the morning. And when you believe them, and they roll you like the john you didn’t know you were, it’s understandable that you’d feel a little burned. That’s my working theory, anyway.

Adams

So I think that in the minds of a lot of sci-fi fans, there’s supposed to be a bright line between “hard” and “soft” sci-fi. In that way of thinking, there are two kinds of time-travel stories: Stories that are interested in answering the question “What if we could travel through time?” and stories that are interested in the question “How can I use time travel to tell a better story?” In the latter, internal consistency matters very little – if the point of your story is that love transcends age and time, then you probably aren’t that worried about internal consistency, since the time travel was always just a metaphor to begin with. In the former, though, the internal consistency matters a little more, because without it, you’re not really answering the “What if?” any more.

I think the “aggrieved” part comes from a few different places. First, there are probably many people who insist on stories being either one or the other. Either you’re just telling stories or you’re trying to engage in serious future-telling and societal commentary. It’s of course a false dichotomy, but it’s one that people make. Second, if a work is perceived as being “hard” sci-fi, then any sacrifice of logic/consistency for the sake of broader artistic motives provokes a “Hey, you got fantasy in my sci-fi!!” response. And lastly, for people who LIKE the hard-nosed no-compromise sci-fi, they’re inclined to look for it everywhere, even where it clearly doesn’t belong.

If all you have is a degree in Formal Logic, all you see are syllogisms.