We’re just fascinated with this movie. We can’t help it, OK?

Perich

I was reading some Reddit reactions to R.I.P.D. this morning and found one comment where someone complained about the movie setting up “in-universe rules” and later ignoring them.

I haven’t seen R.I.P.D., so I don’t know if this is a Chekov’s gun complaint. But based on other comments I’ve seen lately in other contexts, I suspect it’s not. I suspect rule-adherence is valuable in and of itself.

There seems to be a decent subsection of fans of genre films and genre books who think that the “rules” under which magic or fictional technology operate are an important artistic consideration. If a setting has innovative rules for magic, that is noteworthy. If a story establishes the rules of magic and then breaks them, that’s bad.

As a critic, connoisseur, and erstwhile artist myself, I don’t understand this aesthetic. For me, what makes a movie or book good are considerations like plot, characters, imagery, tension, tone, etc. The idea of keeping score with some eye toward perfect consistency is alien to me. In fact, some of my favorite films fail this benchmark without losing any points in my eyes (e.g., in Casablanca, once Major Strasser’s been shot, can’t all three of them get on that plane?)

To use the example we always return to: in A New Hope, the rules of The Force are never clearly established. Apparently, The Force can mimic giant animal noises, hypnotize people, let you see in the dark, choke people at a distance, preserve your spirit as a Force ghost, and aid in missile targeting. Nowhere is this laid out. Yet I would never say the movie suffers for it.

So whence this fascination with the rules? And what do the people who like rules get out of it?

Fenzel

This is an interesting question, and I think there are a host of reasons why people get upset when sci-fi / fantasy rules are broken.

Some of it is emotionally unhealthy. People who get in cycles of anger, don’t spend enough time outside of fantasy universes and are looking for reasons to be upset. But I’ll put that aside for a moment.

I do think it tends to sap a lot of dramatic tension. It can demonstrate that the filmmakers have failed to set up what is at stake and what obstacles characters need to overcome to get there. This is especially true when a constraint seems really difficult to accommodate within your genre, so people expect to be surprised by how it’s dealt with (Revolution is a good example of this – people wanted to see how the show dealt with its constraints, and then it just didn’t).

Related are instances where the rules set up guard rails for the story, forcing the characters to do the fun things in the movie rather than much more obvious things that nobody wants to watch. When those rules are broken, it raises the question of the characters aren’t doing the obvious thing, which the filmmakers had hoped to dispel at the beginning of the movie.

Guard rails, Marty!

Another good example of both of these is the 1.21 jigowatts and 88 miles an hour rule in the Back to the Future movies. They set up challenges for Marty and Doc to accomplish, and they prevent them from just using the time machine whenever they get in trouble. Mister Fusion lifts one of those restrictions so the movies aren’t too repetitive, but they keep the other one. If they got rid of it, it would be shitty.

Others work as jokes or stunts, where the only reason the rule is even mentioned is foreshadowing something that will happen later. You make a mental note to look out for that thing and if it never shows up or shows up but drops the ball, it’s disappointing.

A good example of this is crossing the streams in Ghostbusters. It’s mentioned early on that crossing the streams is really bad and if anyone does it, something terrible will happen. Later, they disregard this and cross the streams anyway, but the characters acknowledge the previous rule, and the scene where they cross the streams is awesome, so we’re not disappointed. It’s not about getting it right; it’s providing a payout like you promised.

The trick with that is when the filmmakers think they are providing an awesome payoff of foreshadowing, but really they’re just doing bullshit. Indiana Jones finding the Crystal Skull aliens and they do crazy light show stuff and then just leave is a good example of this.

It’s easy to point out that the scene makes no sense based on what has been established about these aliens and how there’s like mind control powers involved and global domination or whatever. But the real problem is the whole sequence is terrible for plot, story, character, pure awesomeness–basically every conceivable reason. We complain about the violation of the movie’s own principles, but we’re saddened and upset by the violation of the movie’s own expectations.

Midichlorians are like this. They’re a setup with no payoff. The Force didn’t need them because The Force was already providing great payoff scenes based on the vague expectations it had already established.

At the end of the day, it’s not that different from anything else set up about a character. If there’s going to be a big twist, and the teacher is going to turn out to be a stalker/murderer, the characters are writing better do it credibly, and it really helps if the reveal itself is awesome.

It’s also an element of production value. Shoddy adherence to your own universe’s rules can be seen as a sign of laziness or lack of focus and attention to detail.

A good example of this is in Star Trek: First Contact, when at the end of the movie Worf says the Vulcans didn’t detect the Enterprise because they were masked by the moon’s gravity. That’s nonsense and not consistent with how the Star Trek universe works, but it mostly just feels lazy and sloppy and isn’t a big reason to be upset.

“It’s deliberately sloppy.”

Doctor Who gets away with a lot of rule breaking, because it had been established that its production is deliberately sloppy, and it’s justified by the characters and makes sense for the story. Plus, the payoffs are usually awesome even when they are dumb and make no sense. But when they fail to deliver an end-of-episode or end-of-arc payoff, all of a sudden the shortcomings of the sci-fi world-building they’ve done feel much more glaring and obvious.

“One of the most powerfully overthinkable moments in the last 20 years of film”

Ultimately, it’s about whether the story is satisfying or not. I feel compelled to return to one of the most powerfully overthinkable moments in the last 20 years of film, when the tears of Pikachu restore Ash Ketchum to life after he is turned to stone in Pokemon: The First Movie. As far as I know, this happens for no reason. But the story of Mewtwo is all about the pain of isolation and the indignity of being used by people, so the Lazarean tears of Pikachu, the ever-loving, ever-loveable friend-not-servant work to tie the movie together, despite making no goddamn sense.

Adams

I fully admit I sometimes have the same complaint about movies that forget their own in-universe rules – and I say “forget” because violations of the rules, on the other hand, are sometimes OK. As Pete mentions above, we don’t mind when the Ghostbusters cross the streams or when Harry Potter survives the Avada Kavadra curse, because there are good story-centered reasons for the violations, and the “rules” are at least acknowledged.

“Probable impossibility is preferable to an improbable possibility.”

I think the complaint with in-universe rules being broken is that it takes you out of the action. For a certain type of person, we pay a lot of attention when the world-building/rule listing is going on. And when those rules get broken, it’s jarring. Your suspension of disbelief is hard-won, and all of a sudden you’re wrenched back into reality. It’s Aristotle’s whole “probable impossibility is preferable to an improbable possibility.”

There’s also the matter of stakes. We accept that Wizards exist in Harry Potter, and we accept that they can do fix all sorts of problems that would be hopeless in our own world – but because there are limits on what they can do, you still have conflict. Voldemort is THERE and we can’t get there because of the rules of magic, so we will need to do X and Y clever things to get around it.” If the rules aren’t really rules, though, then it’s hard to keep the feeling of conflict/stakes alive.

That said, there is definitely a current of “poking-holes-for-the-sake-of-poking-holes” that runs through a lot of those criticisms – it’s fun to feel smarter/holier-than-thou by poking holes in the rules of the universe.

Fenzel

Fictionally, plot-hole poking probably serves a similar purpose to gossip – you talk with your friends about the things other people do wrong to fill a need to understand rules in a way that validates your own preferred behavior.

If two friends of yours are sleeping together secretly, does it really matter to you? Probably not. But you might still talk about it because it is satisfying and exciting to do so – and it’s satisfying and exciting to do that because social groups or organisms that self-police behavior socially are advantaged in the struggle for survival.

Mlawski

I had an overlong sociological answer, which I’ll boil down to

a) it’s the rise of geek culture and

b) the rise of the knowledge economy (related).

“The geek with the most knowledge has the most power.”

Basically, geeks like memorizing intricate (crunchy) rule systems and engaging in rules-lawyering. It’s a power thing. The geek with the most knowledge has the most power. (See: Comic Book Guy stereotype.) Also it can be fun. Geeks are the new pop culture critics, because they run the Internet and no one reads newspaper critics anymore.

These points fit in with the larger trend of gamification in society. There’s this idea nowadays that life should be a mathematical equation: plug in knowledge of scientific/economic/pickup artist rules + use knowledge well => money, sex, and power. Or, for religious fundamentalists: knowledge of the rules + following the rules => Heaven. So in the movies, rules/mythology must be clear and constant, and the characters must use the rules intelligently. Those who don’t are “too dumb to live.” Movies that operate in a more surreal/pomo/random universe are not for geeks and therefore are relegated to indie-land.

Big exceptions:

1) Like Pete, I thought of Doctor Who. It kind of wrecks my whole argument. I think Who gets away with its rule-flouting because of nostalgia and because it has such an extensive mythology. That gives the uber-geeks a different way to exclude people deemed not knowledgeable enough: “Ugh, I bet you just like the new Who. You probably can’t even name all the companions between 1970 and 1975.”

2) Game of Thrones has ushered in a trend of fantasy that is less rules-based. This kind of fantasy is allowed when it is violent and gritty. As a member of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, I’ve noticed many fans and some creators have this idea that rules = logic = SFF “hardness” = male = better, while fewer rules or rule-breaking = emotionalism = “softness” = girly = gross. Thus rule-bending is only allowed if it is balanced out with decapitations, zombies, and rape scenes.

(I’m probably being really unfair to geeks right now, so here’s a disclaimer: I am a geek, most of my friends are geeks, I was just at a geek convention and everyone was really nice there, and I’m going out tonight to play Carcassonne and Settlers of Catan. Ni!)

I feel we should also note that while this is a growing trend in modern pop culture, it’s not completely new. Back in the 19th century there was a lot of discussion about rules or the lack thereof in Gothic horror and detective stories. If I’m remembering my Gothic fiction class in college correctly, readers tended to prefer the rules-based stuff. In my opinion, those stories were a lot less interesting and scary than the ones that broke their rules or never had rules to begin with.

Fenzel

In it for the LORE.

I’d say under this discussion, “lore” is similar to “rules” in bringing pleasure to systematic thinkers. Game of Thrones has lots of people, myself included, who derive joy from absorbing and processing all the ancillary information. And I think many people still expect that at some point the rules of the universe in Game of Thrones will be explained – though personally I’d very against that happening.

And while this definitely explains some of the cultural fixation on rules in existing movies – even more than that it prompts people to make movies and other art with more elaborate rulesets to begin with – and while the satisfying or unsatisfying payoff of these rules is still anchored in the story, the amount of time and effort invested :/ then in the first place shouldn’t be discounted.

Although I wouldn’t limit the phenomenon to geek culture, either. I recently watched the pilot for Airwolf, the classic 80s super-helicopter show, and was really surprised by the amount of time and effort put into describing the technology and capabilities of the helicopter – even more time than was spent playing cello on a lake for bald eagles. It’s a late Cold War thing that’s all over Tom Clancy books too–people totally geeking out about the arms race.

And I think people similarly have done it historically about cars and guns and all sorts of other stuff too. But the fixation on doing it about universes that are entirely imaginary with no basis in reality is what I’d generally think of as the rising Geek Culture trend.

Perich

Can you guys give me an example of where breaking the rules has taken you out of the story? (I don’t doubt this; I’m just curious)

I can give a few examples of works where adherence to the rules–or even a stringent acknowledgment of them–has taken me out of the story:

(1) There’s a well-regarded fantasy novel by Lois McMaster Bujold, The Curse of Chalion, where the protagonist falls victim to a curse. A little after this happens, there’s a chapter where he and some friends talk about the “rules” of the curse and whether certain actions will or won’t bring down doom upon the protagonist. To me, this is awful. Treating a curse like a footnote in a legal opinion, as opposed to a bizarre and unnatural terror, saps the tension out of the plot for me.

(2) The Jim Carrey theological romance, Bruce Almighty, made a lot of hash over what the few limits were on Carrey’s unlimited power. Every time these rules were referenced in the script, it threw sand in my face.

Lee

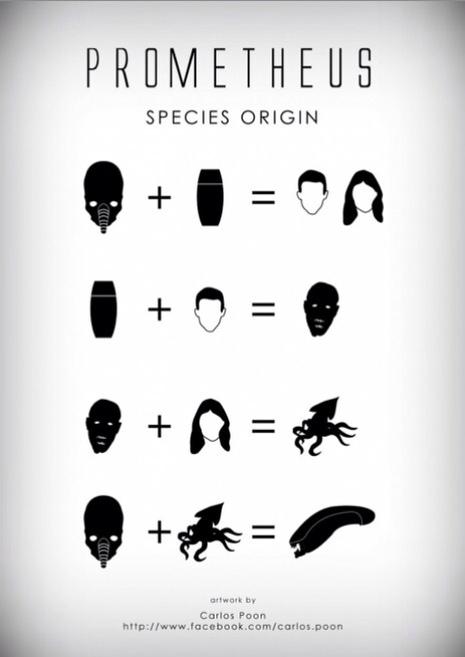

The most recent egregious example of this that comes to mind is Prometheus. (Spoiler alert)

This chart perfectly illustrates the lack of logical flow to the escalating events in this movie.

In a different movie, could the same plot points be used to tell a much more compelling story? I don’t think so. In other instances, I could totally see how a story with logical gaps or internal inconsistencies would fail in the hands of a lesser director (Christopher Nolan’s movies come to mind), but Prometheus is not one of those movies.

Still bitter about this one, in case you couldn’t tell.

Fenzel

(Prometheus spoilers)

Prometheus could have gotten away with more if the space jockeys had talked more and/or had characters we cared about. Then there would be more tension in their conflict with humans. As it was, there was mystery, but not tension.

Also “this is where the alien from Alien came from” is not a sufficiently big reveal to satisfy the setups in the movie. We all already know that the xenomorph is going to show up at some point. Prometheus has buckets and buckets and bathtubs full of windup that makes little to no sense. The black goo is a non-character with no lines that still manages to be the main antagonist. It needs to have something HUGE at the end to justify its use of everyone’s time and to make the nonsense worth it. It really doesn’t.

It’s a lot like Revenge of the Sith. We all know Darth Vader is coming at some point, but by the time we get there, who gives a crap?

Belinkie

Not sure it’s exactly the same thing, but I soured on Looper because I feel like it didn’t want to play by its own rules. It started off with the promise of being a logical puzzle to solve and ended up very new age-y and not really about time travel that much.

Fenzel

(Looper spoilers. Be warned.)

Looper is such a friggin’ cop-out. A lot of bad things happen in a lot of movies. And sure, a lot of those bad things would end for the characters in the movie if they just killed themselves. If Bruce Wayne killed himself as a child, there’s no Joker, and few if any of the bad events of the Batman movie ever happen. If Jeff Goldblum in Independence Day didn’t want to be humiliated by his estranged wife hanging out with the president anymore, he could just kill himself. Everyone else on Earth is dying, so it’s not like he’d miss anything. Problem solved!

The guy in Looper could end the events of the movie at any point by killing himself. But of course he doesn’t want to die–but doesn’t quite live, either–which is what the damn movie is about in the first place.

If the loopers are okay with dying when their loops are closed, nothing in the movie matters. That’s why the scene of the guy being dismembered is so dramatically intense. Why doesn’t he just keep a cyanide pill on hand and take it as soon as the message appears on his arm? Because he doesn’t want to die!

“Hey, I know how I’ll stop Jason! I’ll chop my own arm off with a machete and bleed out so he won’t want to be in the movie anymore!”

As we’ve said, movies that require people to do unlikely things that we want to watch rather than obvious things we don’t want to watch sometimes require guard rails, perhaps in the form of technology or magic (“Doctor Octopus can’t be reasoned with or paid off, he’s under mind control!!”). But some of them are much more basic. The most basic I’ve is characters are generally not allowed to say “Fuck this movie, I’m not a real person with a self-preservation instinct or a subjective experience of reality. I’m just words on a page or lights on a screen, so I’ll just kill myself.”

Looper sets up this survival story about a guy metaphorically trying to evade his own inevitable death, despite the fact that he’s an unhappy and amoral hedonist. He meets these people he really likes and realizes things in life matter, and that he’s caught in this psychological cycle of abuse and he decides to make a difference. Great.

You know what your therapist would never tell you to do when you’re talking about trauma? Kill yourself to spare others the inconvenience of your existence.

For him to but only do that, but to be so cavalier about it when it happens? It’s a betrayal of the most basic premise in the movie – of any movie. Which is that pictures of people on screen are pretending to be actual people.

I’d say that’s another way rules in sci-fi and fantasy can disappoint you: when they serve as metaphors for something in a very specific way, and then they diverge really sharply from the material they represent. Because the vehicle is usually set up to match up plausibly with the tenor of the metaphor, divergence from the rules of the thing the movie represents usually shows up as divergence from the internal rules of the movie as well.

A good example of this is when Jessica Alba has to stand in the middle of the bridge in her underwear in the Fantastic Four movie. “The Invisible Woman” is a weighty title that conjures a feminist critique of the lack of credit women historically got for their work as scientists, colleagues and collaborators of professional men and mangers of homes. That her powers would make her into PG-13 cheesecake is way, way off from what she represents. So it also feels really implausible for the situation and takes you out of the movie entirely, as it’s painfully obvious the real-world filmmakers just wanted to show Jessica Alba in her bra and panties.

This is all a bit off topic, but seriously, the end of Looper sucks.

Also, I never realized that about Casablanca. Man, that’s bullshit.

“Here’s looking at your plotholes, kid.”

Perich

1. I think I get what you’re saying about Looper, but I disagree that it’s a copout. I think it’s actually the point.

2. There are probably all sorts of real reasons why only two people can get on the plane in Casablanca. There’s probably a customs office in Lisbon that would put Rick back on the plane. Or Captain Renault would probably call the Luftwaffe if Rick didn’t keep a gun on him.

The point is, the movie sets up several obstacles: the letters of transit, Major Strasser, Rick’s feelings for Ilsa. Realistically, removing any one of them should be sufficient to get the good guys out of Casablanca, but it wouldn’t be a very satisfying movie if we left the other two unresolved.

Stokes

At its worst, rule-breaking creates plot holes, which, like any other plot hole, can range from “ruined the film” to “oh, who the eff cares?”

In general, I feel like “soft”/vague mythologies are less vulnerable to this… unless you make the rules clear, how does anyone know that you’re breaking them? What seems to provoke the nerdrage is sci-fi that aims for hardness and misses.

Pete, are you really complaining about Looper? Or are you just complaining about suicide qua suicide?

Belinkie

Pete, you’re not actually suggesting that no character can change and decide to make a noble Tale of Two Cities style sacrifice, right?

Fenzel

Sadly, I have to say I’ve never read A Tale of Two Cities. As for my problems with Looper, they’re probably have more to do with my problems with cultural ideas of suicide than just my problem with just the movie. I tend to view suicide, barring stuff that would be end-of-life anyway, as a public and mental health issue, and I tend to think stuff that romanticizes it as a rational choice misrepresents what it is in reality.

Of course, there are all sorts of self-sacrifices in stories (like The Core / Armageddon/ Vegeta vs. Majin Buu) that I don’t intellectually or emotionally connect with real-life suicide. I tend to draw a line between suicide as someone might do for everyday reasons versus working a double shift at Fukushima.

I use any excuse possible to put this image into posts. – Lee

Take Terminator 2 for example. If the T-800 were a person instead of a robot and still killed himself, that ending would probably upset me, and I’d probably get in a bunch of arguments about it. Because people generally really don’t want to die, people dying when they don’t have to isn’t a cool thing, and vulnerable people shouldn’t have a bunch of rosy images of the benefits of offing yourself put in front of their faces by our culture.

So, with all that in mind, I’ll draw the line on suicide in a movie earlier than most people.

But there are still cases when I think it’s a cop-out, where people who would very much like to stay alive kill themselves or have an implausibly casual attitude toward themselves dying just so the story can be over quickly.

I see Looper on the wrong side of this divide and would have preferred the main character take less of an easy way out. But as riled up as I get about that, I don’t think it ruins the movie. It just makes it less than what I wanted it to be.

Stokes

What makes Armageddon different from Looper, I think, is that the former is a Utilitarian Nightmare World Dilemma. Either you or your son in law had to die saving the world. Which death, in the long run, will maximize Liv Tyler’s happiness? Choose!

Looper is a different and more sinister beast. For although there is a proximate emergency that Bruceph Gordon Willet’s death is meant to hold off, there’s also a percolating sense that the real reason he needs to kill himself is just that he’s a toxic person who makes the world worse by being around.

Fenzel

Right. And I don’t think he was really that toxic a person. At least not hopelessly so.

Adams

I agree with Stokes that world-building errors are not fundamentally different from other kinds of plot holes, though I think as a general rule they tend to be more glaring in that they’re “unforced errors.” If you’re already bending the laws of the universe to suit your story, and if you’re going to take the time in the script to provide exposition about what those rules are, the least you can do is make sure that you follow those rules.

“I spent the rest of the movie just being annoyed at the inconsistent time-travel logic.”

The most glaring example of a time where I was completely taken out of a story by a internal-consistency error was in Butterfly Effect. There are all sorts of problems with it, but the one that sticks out is the scene where the main character is in prison, and to prove to his new cellmate that he really has time-travel powers, he goes back in time to when he was a kid and slams his hands down on some nails so that he’ll have scars. But this goes against the ENTIRE POINT of the rest of the movie, which is that even small changes will effect the outcome of his life. And it doesn’t make sense anyway – if he had already scarred himself, the inmate he’s talking to would have never known him without scars. When that part hit, I spent the rest of the movie just being annoyed at the inconsistent time-travel logic.

I guess my point is that when you have a rule-setting monologue at the beginning of the movie, I’m primed to pay special attention to those rules. When I watch a movie like Inception, part of the fun of the movie is grinding my gears keeping up with it.

Of course, some internal rule breaking is fine, either because it’s justified by the plot or its so minor as to not be a big deal. But I’m much more upset when the Wizard does something that the monologue about magic at the beginning of the movie said was impossible than I am when some wider rule of science or physics gets broken.

Wrather

As interesting as these digressions are, and as interesting as the typology of rulesets in SFF world building is (mmmm!love me some typologies!), I think we’re begging the question here.

When our complaints imply that art’s most important duty is internal consistency, I think we reveal an impoverished sense of what art is and what it’s for. Dramaturgically, we’ve moved beyond the classical unities, and while I think it’s important for a work of art to have something like integrity (imagine drawing a stick figure in crayon on top of a Rothko — the two things just don’t fit together), I think that we push that demand too far when we insist works of generic art resolve like something from the Dell Book of Logic Problems.

“I think that we push that demand too far when we insist works of generic art resolve like something from the Dell Book of Logic Problems.”

I understand the wish that the characters and incidents in our stories behave in predictable ways. I think it’s related to the childlike wish that the world make sense, that it conform to our innate sense of cause and effect or to the ideas of justice we develop very early in our lives. I think it’s not merely coincidental that this fanaticism for rule-following comes at a time where we spend more time each day (and are more comfortable) interacting with machines than with humans, which is a relatively recent development in our history.

Great art is surprising and strange and full of mystery. Rule following comes below several things on the list.

But there’s another level, a personal edge to a lot of these kinds of complaints. (And, following Pete, I’m skipping over the unhealthy tendency to entertain ourselves online and off with our own capacity for feeling aggrieved; and I’m going to skip over the phenomenon Mlawski highlights of the ascendency of the “geek” culture, though I think it’s troubling and worth examining in more detail, because it involves the transformation of a maligned outcast subculture into a hegemonic discourse which has become oppressive on certain message boards.)

I think the personal edge has to do with feeling taken for a ride — feeling lied to or used. The corporations behind movies and TV want that geek money, and promise that they love you and will be there in the morning. And when you believe them, and they roll you like the john you didn’t know you were, it’s understandable that you’d feel a little burned. That’s my working theory, anyway.

Adams

So I think that in the minds of a lot of sci-fi fans, there’s supposed to be a bright line between “hard” and “soft” sci-fi. In that way of thinking, there are two kinds of time-travel stories: Stories that are interested in answering the question “What if we could travel through time?” and stories that are interested in the question “How can I use time travel to tell a better story?” In the latter, internal consistency matters very little – if the point of your story is that love transcends age and time, then you probably aren’t that worried about internal consistency, since the time travel was always just a metaphor to begin with. In the former, though, the internal consistency matters a little more, because without it, you’re not really answering the “What if?” any more.

I think the “aggrieved” part comes from a few different places. First, there are probably many people who insist on stories being either one or the other. Either you’re just telling stories or you’re trying to engage in serious future-telling and societal commentary. It’s of course a false dichotomy, but it’s one that people make. Second, if a work is perceived as being “hard” sci-fi, then any sacrifice of logic/consistency for the sake of broader artistic motives provokes a “Hey, you got fantasy in my sci-fi!!” response. And lastly, for people who LIKE the hard-nosed no-compromise sci-fi, they’re inclined to look for it everywhere, even where it clearly doesn’t belong.

If all you have is a degree in Formal Logic, all you see are syllogisms.

I think Fenzel nailed it at the outset: when the creator of a work of dramatic narrative (like films, TV, novels, video games, short stories, etc) establishes a distinct set of in-universe rules, they’re asking me to put my faith in them so they can tell me a good story. When the creator then gratuitously violates those rules, they violate that faith, and I’m no longer as engaged in the drama as I was because I’m on my guard against future abuses of that faith.

Wrather’s comment towards the end is a bit of a straw man, because it initially conflates “art” with “dramatic narrative”, and then sets up a pretentiously narrow standard for “great art” (“surprising and strange and full of mystery”). Not every work of art needs to be internally consistent to be satisfying or respectable, because not every work tries to, or even needs to, succeed as a dramatic narrative.

Taking that as read, then, what does it benefit a creator to spell out the “rules” explicitly? When the creator violates the rules, it alienates a portion of the audience. But when a creator adheres to the rules, that’s … satisfactory? Why not just leave the rules vague (a la A New Hope or The Matrix)?

“Why not just leave the rules vague (a la A New Hope or The Matrix)?”

I think that is the whole point. If the creator doesn’t want rules, then he or she shouldn’t make them. It is just a waste of our and their time explaining the rules to us if they aren’t going to matter.

It all depends on what you’re trying to accomplish.

With Star Wars the climax of the movie is Luke trying to decide if he’s going to put his faith in the Force, if he’s going to commit to this thing he doesn’t fully understand. So the fact that the audience doesn’t fully understand it either helps us empathize with him.

The Matrix is all about Neo learning that he doesn’t have to follow the rules of his universe. That’s the whole story.

Typically the rules are established to give the characters obstacles to overcome, and to create tension. If you’re telling a Superman story, and you don’t establish what his powers and weaknesses are, then no one’s going to care when you show Lex Luthor finding a chunk of Kryptonite. No one’s going to understand why Superman is jumping off buildings. No one’s going to be able to follow the action, unless you establish the rules. And if you establish the rules, and then in the end Lex Luthor’s Kryptonite bullet bounces off Superman’s chest, then what was the point of everything that led up to that moment? If you set rules to create tension, breaking those rules invalidates all of that tension, which pretty much invalidates the entire story.

Fair enough, there’s some slippage in my definition of terms. Not all art is narrative, not all narrative is dramatic. And I think the focus of this article is dramatic narrative. So that could have been clearer.

But I think there’s another conflation of terms going on at the moment, when we mistake a work’s potential for intrinsic harmony or integrity, which are qualities that encompass many parts of a work as well as their relation to one another, with the logical consistency of its world-building, which is a much narrower concern. Both qualities can be important, and have been more and less relatively important in different times and places, but they’re different from one another, and they’re not always necessary. There’s no checklist of elements that can make a really good story (which is why I think they’re surprising and mysterious).

So I’d expand your last sentence to include dramatic narrative in the list of art forms that don’t need to “be internally consistent to be satisfying.”

I’m actually surprised that the phrase “relation to one another” didn’t come up in the main discussion. To me it seems to be the key factor.

Establishing a set of rules and then disregarding them is a path to disatisfying art(Fenzel’s point); and establishing a set of rules and creatively breaking them is a path to surprising/exciting art.

The reason it can be both is because it’s not a strict mapping of rules made to rules followed, it’s about the relationship the rules have to the narrative.

So the difference between “plot hole” and “subverted expectations” is the status of that relationship. Do the Rules (followed or broken) and the Narrative complement each other?

If the rules and narrative meet briefly and then each go their own directions we feel cheated.

{Butterfly Effect?}

If the rules and narrative meet, bicker, divorce and/or one murders the other then we wind up frustrated and annoyed.

{Prometheus}

If the rules and narrative meet, fall in love, and raise babies that share some qualities of each then we feel satisfied and pleased.

{Back to the Future, The Terminator, Alien, Casablanca… lot’s of stuff I love}

If the rules and narrative meet, and spend their time getting hot and sweaty with each other (maybe each taking turns on top) then we feel excitement and surprise.

{Fight Club, Dr. Who, The Maltese Falcon… lot’s of stuff I love}

So this theory has both objective and subjective components. Objectively you only get satisfying payoff moments when there has been an interesting ongoing relationship. Subjectively we respond to different elements when classifying that relationship.

Great discussion, and thanks to Perich for starting us down this rabbit hole. As a “recreational” writer I enjoy/benefit from these sort of meditations.

Every story has rules that can or can’t be broken – even non-sci-fi or fantasy ones. If you start a story by saying, for example, “Sports team X can’t be beat,” and then at the climax, the scrappy underdogs beat team X, it’s satisfying because the protagonists have done the impossible. If they beat team X in the opening 10 minutes and nothing is made of it, it makes it feel like the rules don’t matter. (or the rule could be – “he’ll never find love” or “the natives won’t defeat the colonists” or whatever – the rule gets broken only after the protagonist goes on a journey to accomplish the impossible)

Matrix is interesting, because the rules are broken at the end, but it’s treated like a big deal. Or, the crossing the streams example in the article. If the climax of the movie had happened at, say, the mid-point, and nobody had even acknowledged that anything unusual had happened, it would feel more like a violation.

So I’d like to propose that the “rules” aren’t important in that they can’t be broken, but more that they have to be broken in a specific way, and at a specific point in the story.

Nah, the “deus ex machina” style of resolving the plot problems (and that’s what most people would call “breaking the rule of universe” nowadays) was considered “bad art/plot hole/whatever” since at least Middle Ages. Or even ancient Greece, come to think of it (probably the ancient Middle-East had some rules about that, too, I simply don’t remember them now). It is connected to the “geek culture/sci-fi/fantasy” as the Plato is – all that genres exist in the world shaped by his ideas. Not other way round.

(not every flow breaks the rule, by the way – the fact, the the main hero can survive almost everything is considered the rule for action films and nobody complains about it)

(

though I notice that the most of “new media/web theorists/ludologists” tend to, indeed, treat many old ideas as something new, fresh etc. just because they exist on the Internet, too; fascinating thing. I guess it proves we truly live in the late modern era – modern is the only reference point for our society; “traditional” means mostly “19th century/industrial”, even if it was just a fleeting fashion in human long history)

Also, no, in the Casablanca they cannot go to the plane. They still have only two visas and there were the problem of the love triangle.

But, of course, I’m fan of formalism, not interpretations based on sociological categories, so I’m biased, too – still, I’d say it’s the problem of composition and formal aspects of the plot (not knowing how to go to the next scene or resolve the problem within created boundaries or creating a wrong rules; either way, the lack of imagination, serious flaw), not the genre-inducted issue.

“Dramaturgically, we’ve moved beyond the classical unities, and while I think it’s important for a work of art to have something like integrity (imagine drawing a stick figure in crayon on top of a Rothko — the two things just don’t fit together) … Great art is surprising and strange and full of mystery. Rule following comes below several things on the list.” – that’s very… western and modern-biased sentence (and untrue, from the academic point).

If one isn’t the die-hard Hegel fan, one should be aware that the “moving beyond” is in itself a theory/belief, not a fact (the theory the progress of time is connected with the progress in culture/morality/etc.), quite dangerous in itself (maybe any theory is). And, of course, it’s a judgement, since it implies that the classical integrity was something bad.

Second, it’s not only classical unities, classical unities was broken thousands years ago – following the rules was considered one of the most important parts of techne/ars till… well, today, but since there was quite a bit of redefining the role and rules of art in 19th century, let’s say “till 19th century”. In the Occidental culture, of course. The great works of art had been made before the 19th century and not in the Occidental culture – and many of them hadn’t been created to be “surprising” or “mysterious” etc., simply because it would considered, ekhm, bad art in their times. Or not art at all. E.g. “pathos”, “emotions”, “harmony”, “truth”, “beauty”, “following the rules”, “education value”, “moral value” etc. were considered more important in some times (though, of course, it depends on the era; the Baroque poetry considered “surprise” and “strangeness” very important).

And even the Romanticist would not say that one should break the rules, they simply redefine the concepts of what is the most important “rule”; many artists and most of teachers, even nowadays, agrees that the art is about being able to create within the borders. That the rules (and sometimes breaking them, but in a meaningful way) are what art is made from. The rules are the art, art is nothing without the rules, no rules no art etc. The one thing which, by the most popular formal theory, differs “the art” from anything else, is – surprise – the… “addition of the formal/aesthetics factors” – “superfluous addition of rules”, “superfluous rules” – that what art, from many perspectives, is. Of course, there’s the issue of who creates the rules – the tradition, the common sense, the artist, the public, the client etc.

And, of course, quite a few, if the most, agree, that one should follow the rules if breaking them isn’t significant from the point of interpretation, if it doesn’t add anything to the work. Breaking the rules in sake of breaking the rules would considered silly or pretentious in most cases.

“stick figure in crayon on top of a Rothko” would an nice, though boring piece of art in my opinion. It would be just repeating the Duchamp gesture. Quite popular in modern art. Boring, but if I need something to my dining room I may buy it. It would be cheaper than Rothko after all. ; )

(the comment was written from the western, modern POV; the author wants to say he deeply respects other cultures and times and is aware that the post-Romanticism struggles are probably terribly boring to them ; )))

All interesting points, many of them well-taken. Maybe my rhetoric reached too far beyond the limits of the discussion, which has as its starting point a summer action movie and should probably be understood within that context. I certainly wasn’t trying to encompass every work or theory in the global history of art. (I’m not sure such a thing would ever be possible—or even desirable.)

But I want to address specifically the question of “moving beyond,” because my contribution to the article is an argument for greater richness and diversity in the kind of we acknowledge is valuable. And you’re right, an invocation of “moving beyond” is a move that, rhetorically, seeks to supplant an established “inferior” state with a new “superior” state. Which wasn’t what I meant.

What I meant was that contemporary, commercially viable movies—like summer action movies—have available to them a greater variety of dramaturgical models than the ones that seem to dominate in the marketplace. And it’s very interesting when we see a greater diversity in the kinds of stories that get told in that context.

I’m not going to evaluate whether drilii is smarter than me by a factor, or just doesn’t care about things like syntax and semantics.

… so without judgement I point out that I enjoyed this comment (and got more out of it) when I viewed it through the assumption that it’s a Markov Chain generated from old college notes.

ps. For fun with the quasi-sequitor results of Markov chains check http://www.codinghorror.com/blog/2008/06/markov-and-you.html

THANK you, Ben – I knew I couldn’t have been the only one to be driven INSANE by the stigmata scene in Butterfly Effect. If I don’t misremember completely, his reasoning was that his cellmate was religious and that’s why the character wanted to make mysterious scars appear on his hands. Which is a really far-fetched idea to begin with. But then he goes and inflicts injuries on his hands publicly, in school – an event that must have SOME consequence on his life, right? Right? At the very least, maybe, a talk with a counselor? And as the TITLE of the movie tells us, this will have other unforeseen consequences, apart from the scars. As you said, it’s literally the entire point of the movie. It would be like calling a movie “Earth’s gravity is so strong that nobody can jump” and then have a character jump up a ledge to escape some minor quarrel halfway through the movie.

Come to think of it – it’s been almost a decade since I’ve seen that movie, and its rule-breaking still bugs me on a strong emotional level. I guess this goes to show the relevance of this article’s topic.

For my money…or however “time watching TV with commercials” translates to money…I think Adams (sorry, still learning your names) nails it, “I guess my point is that when you have a rule-setting monologue at the beginning of the movie, I’m primed to pay special attention to those rules.”

John Rogers spent the first three years of “Leverage” setting up the show as an all-but documentary on high-tech con artistry in the DVD commentaries, on his blog, and in the story. It was fun, it was nerdy, it was great. Then by the fifth season, when there gaffes in the tech, his answer was basically (paraphrasing), “Yeah, we thought about that in the writers’ room, but only you, me, and [very small decimal point percentage] of the viewers would catch it, so whatever.”

Which in the long run is okay. He’s making a TV show, which is a beast with a million moving parts, so it’s not going to please everyone every time. He’s the guy who wrote “The Core” (a fun movie, with the best insult ever) which means he knows when to go for the human-side of the story over the technical-side. And you know, if it were “White Collar” or “Psych” making those gaffes, I wouldn’t bat an eye at them.

When a TV show, either through its narrative or commentary from its creators, asks you to trust its know-how, and you do, and then it starts asking you to ignore it’s mistakes, there’s a sense of betrayal that you (well, I anyway) don’t feel from shows that start off without asking for that trust.

I can only speak for myself, and I am very aware I am one of those geeks who quite often enjoys learning the rules of fictional worlds more than the stories set in them, but I think shows could go a long way to avoid the nitpicking backlash if they injected something akin to the “timey wimey” excuse from “Doctor Who” into their narratives. Take the Transformers Wiki (http://tfwiki.net/) for instance. Fans are quite capable of building their own internal logic for series (serieses?) that promise nothing more than robots that turn into cars, something that’s worked out pretty well for Hasbro over the last few decades.

I don’t, though. I tend to process things on an emotional/intuitive/image level. Things need to make EMOTIONAL or SYMBOLIC sense, not logical sense

Suspension of disbelief. That’s what this whole discussion boils down to. If establishing and breaking rules leads to a loss of suspension of disbelief, then it’s bad. If having soft, undefined or poorly defined rules still allows for suspension of disbelief, for example in Star Wars or Game of Thrones, then it’s fine.

As a lesser point, having clearly defined rules and sticking to them can be satisfying if it fits elegantly into the narrative, but it is not inherently satisfying if it lacks elegance, because it is the elegance which is satisfying, not the simple adherence to rules.

The most interesting thing to me about the undefined rules in Game of Thrones is that they are just as mysterious to the characters as they are to the audience, which allows us to maintain suspension of disbelief. In other words, the rules might be consistent, we just don’t know what they are. Also, I would emphasize the point about lore- in fact Game of Thrones does have consistent rules about things like inheritance and succession, trials by combat, knighthood, marriage alliances, and other aspects of feudalism which establish the social/political/economic structure of Westeros (even if the consistent rule is sometimes “the people with the power make up the rules”).

I’d be curious to see this conversation applied to the rules in “Lost.” That was a series where the rules weren’t clearly defined at any point, and that was the point – the show was a mystery show where one of the big driving forces was the question “What are the rules?” And then, SPOILER ALERT, the final reveal was “The rules are whatever our God-analog feels like them being” which was an incredibly dissatisfying conclusion for a lot of fans (including myself). Given the mythology set up in the series, the existence of Jacob and his power to just kill people or heal them or banish them from the island or let them return on a whim didn’t actually violate anything the audience already knew, but it still felt like a cheat to a lot of people. So, maybe it’s not even necessarily a question of “what are the rules” but also “why do we have these rules?” and “do those two questions fit together in a narratively and logically satisfactorily way?”

There were only two Letters of Transit and the paperwork would be checked in Lisbon. Whatever mistakes Casablanca may have, that wasn’t one of them.

-The Gneech

In Casablanca, regardless of whether all three could or could not board the plane for bureaucratic reasons, Rick doesn’t get on the plane because Laszlo is important to the war effort, and Ilsa is important to Laszlo. The events of the film lift him from his general malaise and empty neutrality, and he realizes that he needs to let the good guy have the girl, for the good of western civilization.

Adrian and The Gneech, Well stated!

And clinching the arguement that this is NOT a plot hole in Casablanca is the fact that it’s actually an application of a rule set earlier in the film:

Captain Renault: The plane to Lisbon. You would like to be on it?

Rick Blaine: Why? What’s in Lisbon?

Captain Renault: The boat to America. I’ve often speculated on why you don’t return to America. Did you abscond with the church funds? Did you run off with a senator’s wife? I like to think you killed a man. It’s the romantic in me.

Rick Blaine: It’s a combination of all three.

Even before all the other factors come in to play it’s established that Rick has always had the option to return to America, but that it would be a defeat for the character.

Looper bother the hell out of me. It spent 20 minutes setting up all these rules only to disregard them in favor of telling a totally different story. And then JGL kills himself to stop the movie? It gives me a headache just to think about the time travel paradoxes.

I am 100% with Fenzel about suicide. It isn’t something to glamourize. Such things are very upsetting, and potentially triggering, to those of us who have struggled with suicidal thoughts and depression.

I think there are two kinds or rules: rules of the genre (which are more akin to expectations) and rules created by the author. As mentioned, a strict set of rules is not always necessary or optimal, especially for more “soft sci-fi” (i.e. Star Wars 4-6). The only reason I can think of for strict rules, is using the rules to do something AWESOME. Rules can also be a source of conflict/an obstacle.

There have been SO MANY instances where I was taken out of the story because an author violated the rules, or because I got confused thinking about all the rules. My prime example would be Death Note. There are so many rules and they act as a sort of railing to prevent the characters from doing things that any normal person would do. Why can’t the Death God just kill the enemy? Oh, there’s a rule against that. The rules are there as an obstacle.

It all comes out to set up payoff. If every episode of Battlestar Galactica is going to begin telling me the Cylons have a plan, I’m going to be pretty irritated when they don’t have a plan. When a piece of media promises me a payoff and I don’t get it, I feel betrayed. The same happens for unearned payoffs, like out of nowhere twists in some thrillers (Side Effects).

Film Crit Hulk goes on about this, in that we are noticing plot holes because we are not caught up by the story (emotionally) and are looking for reasons why (intellectually) and picking on the plot holes as justification for why the story isn’t working emotionally/on a character level.

And one example of this, for me, is the movie Upside Down, in which the movie fails it’s own basic rules for the universe in the actual trailer!

http://jamasenright.blogspot.co.nz/2013/02/whacking-physics-upside-down-head.html

(The story was not great, and I get the physics was simply a way to tell another ‘two people from different lives’ love story… but it still failed in very basic ways.)

The excellent piece you are referring to: http://filmcrithulk.wordpress.com/2011/06/07/hulk-essay-your-ass-tangible-details-and-the-nature-of-criticism/

The article is a perfect companion to this discussion, and only further reinforces my fantasy of a Hulk guest appearance on the podcast for a discussion of art, film criticism, and overthinking ‘it’.

A must-read for all overthinkers!

This Film Crit Hulk article is also highly relevant:

http://badassdigest.com/2012/10/30/film-crit-hulk-smash-hulk-vs.-plot-holes-and-movie-logic/

I know the all caps make these articles hard to read–or at least skim–but do find an hour or so to read through them. Totally worth it.

1. The flow chart regarding Prometheus is ironically how I saw the film. Great to see I’m not alone with that view of the film and it’s themes.

2. You are forgetting a major thing about Casablanca though: the production code.

Rick could never get with Ilsa because the production code would refuse to allow any ending where Ilsa left her husband for Rick. To get to a Rick/Ilsa endgame, you would have to toss in a third hurdle: how to kill off Ilsa’s husband, in order to satisfy the jerk-ass censors who were obsessed with preventing reality from entering into the films being seen by the masses.

You mean like falling off a cliff while trying to take a picture?

I think the whole problem of rule breaking in media, especially film, is endemic of many problems of stories that, as people have come to try and make not just books and movies but stories in a more efficient and “profitable” fashion have done things that under more natural settings would not be necessitated.

My favorite most hated example of this was from the Will Smith version of I Robot. I hated this movie so much. It was so dumb and annoying and cloying and if you like it can’t trust you as a person. I’m sorry but that’s how I feel. The beginning of the movie emphasizes that Robots can’t kill or harm themselves. These are the rules of robots; set in freaking stone by narrative and narration. Then our idiot protagonists find that our good robot has a secondary brain that just somehow overrides the three laws. Woop dee doo! It hurt my head so much that there was just a random “it overrides things just because” solution to what was otherwise supposed to be a mystery. The fact that the very premise originally relies on using consistent logic to divulge answers and then the movie just throws on the “magic solution” switch to rush to a happy ending that was so dumb it made my head hurt.

A more recent addition is recent seasons of True Blood which have been both hilariously enjoyable and horrible dumb for innumerable reasons. Some of which derived form plotlines nobody likes or cares about and how half the cast is so completely boring and dumb, but I digress. Some of the newer additions are that our primary vampire, Bill, is now the avatar of a vampire deity and can just break rules wimbly nimbly. He can walk into people’s houses as he likes and is invincible. I’m not even kidding. He’s basically vampire superman. What is the point of having a show about vampires if the very rues about vampires can just be disregarded?

Of course a lot of this is just throwing in twists and turns in order to make “the stakes higher” even though they often do not. I partially blame the American education system for not introducing Americans to the idea that story structure can be simple and still be good.

However. I also enjoy shows that don’t necessarily have rules, but have a lot of storytelling based on relationships between characters rather than outright rules.

To be fair to I, Robot, it, at an accelerated pace, makes the conclusions made by Asimov regarding the Zeroth Law.

I still really dislike it.

I don’t think this concern for rules is just a geek thing, or just applies to fantastical universes. There are plenty of fictional works where the importance of the rules of the Real World are foundational, and where casual violations of those rules would be hugely unsatisfying. Practically every procedural TV show operates in this fashion — we know that Lenny Brisco can’t beat up a suspect to get a confession, and that Greg House can’t cure cancer with magic beans. (Indeed, one of the most egregious violations of Real World Rules for me was when House used an fMRI machine to literally see someone’s dreams — it was an absurdity too far.)

Often, violations of the Real World Rules in these shows are used to produce tension and drama — we get worked up when Jack Bauer ignores the rules and tortures suspects to get a confession. But if the rule-breaking isn’t for dramatic effect, and isn’t highlighted, we usually let it go, like how Jack gets across LA in heavy traffic before the end of a single act.

Now I know that some of these examples of Real World Rules are more cultural/legalistic instead of the equivalent of physics, but I think the concerns still apply. All rules in fiction are largely about setting narrative expectations, and Lenny Brisco behaving like Vince Mackie is just as much a violation as Highlander turning out to be an alien. I don’t think that geeks are asking more of their genre fiction than we do of Real World stories — in both cases, they need to be consistent with their expectations, and how they play with the rules. It’s no more silly for geeks to be upset at midichlorians than for medical drama aficionados to groan at impossible cures, or for legal shows fans to complain about obvious errors of law.

The approach taken by Brandon Sanderson (“Sanderson’s First Law”) makes a lot of sense: “An author’s ability to solve conflict with magic is DIRECTLY PROPORTIONAL to how well the reader understands said magic.”

His full blog post on it here: http://www.brandonsanderson.com/article/40/Sandersons-First-Law

I honestly can’t say anything more intelligent or particularly original beyond what’s he’s written, so just read that. ;)

Having the idea of rules and rules breakage sloughed off as Geek/Nerd rage is demeaning. Every movie ever made, fictional or documentary, is its own universe and has to work within those constraints. The rules may not be explicitly stated but they are there and if the makers break them, the movie (or any creative endeavour, really) is tarnished and becomes much less of an art.

Take one of the largest universes out there that’s not sci-fi. The Bond franchise. There’s never been a rule book but I betcha most of you can name a bunch of things that are sacrosanct in that universe. Every time there’s a list of “the best Bond movies” one is consistently near the bottom. Die Another Day. It’s not because of Brosnan who was considered one of the better Bonds up to that point, it’s not the script because no script holds that much power in the Bond universe, it was the car.

The car is a minor sideshow at best. It doesn’t even matter much to the plot. But… it’s invisible and that’s just not on. Having an invisible car, no matter how plausible a tech it is, turns Bond into Wonder Woman. The genre has become fantasy instead of the action/adventure it’s supposed to be. It breaks the rules, badly, and the audience, mostly made up of non geeks I might add, is not happy about it. It’s no wonder the Craig Bonds have been mostly gadget free.

Why would it be fantasy if they explained the tech as being analogous to the real life invisibility cloaks that were in the news at the time? Cool tech has always been a part of the Bond franchise, and the Craig bonds spoil this with its absence by basically turning it into a bland Bourne clone.

If you want to complain about fantasy intruding into Bond, the wretched Moore debut “Live and Let Die” is a better case as it implies that the villain escaped his explosive death by voodoo (you hear him laughing at the end).

Because an invisible car is fantastical. The explanation of the tech is moot, most exposition about the use of props in movies is bafflegab. Nobody really cares what it means, just that it sounds reasonable. Do you care how a light sabre works? No. It looks real cool and in a fantasy/sci-fi genre it’s solid gold. Put it into Cumberbatch’s hands as he’s racing around London in Sherlock and it would look ridiculous. People do not want to see major fantastical gadgets in a Bond flick. Remote controlled BMW’s, plausible. Funky Omegas? Ok, because they’re small. Pens, cameras, bulletproof whatevers? You’re heading into parody and there’s a reason Q ended up being played by Cleese. It was remarked on in Skyfall.

I think it is nerd rage, though. And its only specific kinds of geeks. I’m a literature/music geek and I only demand that things make emotional, symbolic or metaphorical sense. I don’t care if they follow some kind of ‘logic’. The real world makes no logical sense either!

I feel that the end comment about the point of the story is the real place where Looper falls down, even without all its time-travel inconsistencies (the Butterfly Effect scar problem being equally relevant to Looper). I’ve literally never endured a story as hung up on its madonna/whore complex as Looper – the story literally has no space for women except for prostitution and motherhood. So when it tries to rest on the idea that the purpose of its only major female character is to be able to make men not be evil by using the fuzzy emotional power of motherhood (much as Bruce Willis’s nameless, no-lines-for-you wife effected his emotional healing in a motherly manner earlier in the film), it just registers as creepy sexist twaddle. Looper might be able to get away with some inconsistencies and copouts if its underlying point was less awful. As is, there’s nothing to forgive.