Please enjoy this guest article from Arwen Spicer!

If you walk in manga or anime circles, you have probably heard of Trigun. One of the superstars of late 1990s anime, Yasuhiro Nightow’s tale of Vash the Stampede, a zany futuristic gunslinger with a troubled past, remains popular today. Trigun has the hallmarks of an anime/manga hit: quirky characters, terrific art, sci fi, super powers, and a high-stakes battle to save humanity: it’s “deep space planet future gun action!!” to quote the manga’s byline.

But Trigun is more than a madcap action series. Its pop medium notwithstanding, it explores the human condition like high literature. Most stories engage with moral questions on some level. But Trigun’s central theme is the nature of morality itself. It asks, “What does it take to live a truly good life?” Indeed, in this focus on the essence of moral behavior, Trigun has startling parallels to Dostoevsky’s novel, The Brothers Karamazov. (Spoilers follow for the Trigun manga and The Brothers Karamazov.)

Trigun is the story of twin brothers, Vash and Knives, who belong to a species called Plants, as in “power plants,” engineered to generate energy for humans. Plants typically look only loosely humanoid and cannot speak, which enables humans to regard them as machines with no rights. Vash and Knives, however, look and behave like humans and are raised by a caring human, Rem. But Rem has a secret: she knows that the only other Plant to be born looking human, Tessla, was experimented on by human scientists until it killed her.

Young Vash and Knives share a quiet moment with Rem.

When Vash and Knives discover the truth about Tessla, this traumatic revelation sets them down different life paths. While Knives develops a hatred for humans, Vash follows in the steps of Rem, gaining compassion and promoting peace. After Knives causes the deaths of thousands of humans, including Rem, the brothers’ relationship is shattered, and years later, they remain adversaries contending over the fate of humanity on their planet and the best course of moral action.

The Brothers Karamazov is the story of a childish and self-serving father murdered by one (or more) of his sons. The novel asks to what extent each of the sons is morally culpable for his father’s death. Fyodor Karamazov’s four sons each represent different attitudes. Dmitri is good-hearted but capricious; having fought openly with his father, he is the first suspected of the murder. Ivan is reserved and intellectual, a philosopher whose creed, “everything is permitted,” sanctions his father’s murder. Alyosha is a saintly young man, a devout Christian in the best sense, filled with love for humanity; he seems innocent of his father’s death unless his sin is not watching the boiling kettle of his family more closely. Smerdyakov, the disregarded bastard, conceives a hatred for his father and ultimately uses Ivan’s philosophy as moral prop to justify killing him. Throughout the novel, the superstructure of the plot provides a frame for discussion of the nature of God, humanity, religion, right, and wrong.

Both stories juxtapose a modern-day saint with philosophical opponents whose criticisms of his belief system are insightful yet inadequate. Both extract sainthood from a quagmire of family dysfunction through saintly role modeling by a flawed hero. Both advocate being your brother’s keeper and show the deadly consequences of failing to be.

Like Alyosha, Vash is oriented toward love for others and service to them, often letting himself be wounded in the course defending innocents while refusing to kill anyone. Like Alyosha, he is capable of extreme feats of understanding and forbearance, combined with an everyday amiability that wins him friends wherever he goes. But like Alyosha, he’s a lotus springing out of the mud. Both come from childhood backgrounds of profound awfulness. Alyosha was graced with a drunken father, who, among other claims to the fame, once raped a retarded woman. Vash grew up in the shadow of his “sister,” Tessla’s, grisly death. Though his human “mother” had logged ethical complaints against Tessla’s treatment, this action was slight and inadequate, making her arguably complicit in this death.

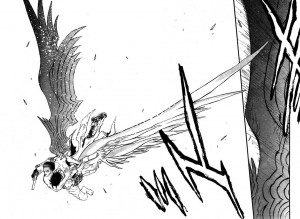

Vash is scarred from many confrontations in which he chose being wounded over striking back.

Both Alyosha and Vash, however, were uplifted by positive role modeling. Alyosha found a better “father” in the Elder Zosima, a one-time great sinner who later found God. Vash has a combination of “sinful” parent and saintly role model in Rem. Both Alyosha and Vash strive to live out the best values of these teachers, while understanding themselves as morally flawed. Alyosha remarks to his brother, Dmitri, that as virtuous as he may appear, he has also set foot on the ladder of sin:

The ladder’s the same. I’m at the bottom step, and you’re above, somewhere about the thirteenth. That’s how I see it. But it’s all the same. Absolutely the same in kind. Any one on the bottom step is bound to go up to the top one. [1]

Vash’s role model is saint and sinner in one: he cannot internalize Rem as his guide without internalizing the part of her that allowed the torture of Tessla. Thus, in his awareness of the highest good (the saintly Rem) lies the awareness that even good can become implicated in the lowest of evils. Such an understanding of human frailty is the root of both Alyosha’s and Vash’s compassion.

Both of these troubled saints have brothers even more psychologically scarred. Of Alyosha’s brothers, Smerdyakov is marginalized as the bastard, and Ivan, having been sent to away to school, grows up lacking some of the family-like supports Alyosha had after being removed from their father’s household. Due to these factors and differences in personality, Ivan and Smerdyakov grow up with darker views of the world than Alyosha, more troubled on an intellectual level by worldly and divine injustice. Ivan eventually arrives at a theory that, in the absence of a defensibly moral God, morality can be discarded. Smerdyakov acts on this theory by murdering their father.

Knives is an amalgam of Ivan and Smerdyakov. He, too, lacks some of the supports Vash profited from. In this case, the brothers’ paths diverge at the Tessla trauma. At the first shock of discovering her fate, Knives faints while Vash remains conscious. As a result, Vash and Rem share a powerful, violent experience of processing this horror together. These ugly moments of conflict between them ultimately help Vash understand Rem’s remorse and reconnect with her. By the time Knives wakes, Vash and Rem are calmer, and Knives never sees how deeply both were damaged by Tessla’s death; from that point on, he feels alone with that horror, and it shapes the rest of his life. Like Ivan, Knives arrives at a theory that killing can be acceptable (as a Plant, he sees eliminating humans as a matter of safety and survival); like Smerdyakov, he is ready and willing to act on this belief.

Both Ivan and Knives are thinkers, as opposed to their saintlier brothers’ emotional instinct for kindness. Both challenge their respective brothers with difficult moral problems. Ivan asks Alyosha to consider how a “good” God can allow the suffering of children and how “good” people can follow such a God. Knives confronts Vash with the plausible reality that Plants will never be safe from human exploitation unless humans are exterminated. Both Alyosha and Vash are too deeply rooted in their own moral sense to be swayed by their brothers’ philosophy. Yet both are troubled by these arguments and fear for their brothers’ psychological wellbeing.

Young Knives plots the destruction of humanity.

And yet both Smerdyakov and Knives suffer the neglect of the saintly brother, who never seems to neglect anyone else. Alyosha is scrupulous is his care for Dmitri and Ivan and even strangers, but he is never more than distantly polite to Smerdyakov and shows little concern for him personally. Vash often shows (understandable) rage toward Knives, while forgiving others who shoot him, beat him, and so on. Both Smerdyakov and Knives, defined as murderers of the parent, seem to forfeit their compassionate brothers’ compassion. Alyosha’s share in the responsibility for his father’s death is intimately tied to his rejection of Smerdyakov. If he has been there for that brother, could he have forestalled the murder? In Trigun, Vash must learn that instead of “dealing with” his brother by physically stopping him, he must love him and let him know he is not alone. The redemption of Knives at the story’s end follows directly from his reunification with Vash.

Vash and Knives united, sharing their Plant powers.

In both stories, this family microcosm serves as a basis for broader exploration of human goodness and darkness. At Dmitri’s murder trial, Ivan states that every man secretly wants to murder his father, leaving the reader to ponder whether, on some level, this is true of him or her. Trigun challenges us to consider how readily we, too, can be Rem, complicit in the senseless murder of other living, thinking beings and how devastatingly far the ramifications of such acts can ripple out.

Both stories extract a moral center from a brutal world by modeling a “Christ-like” approach to humanity. Alyosha does not “fix” Russia, nor Vash his planet, any more than Jesus “fixed” Roman-occupied Judaea. Yet all three propagate compassion by showing compassion to others. In The Brothers Karamazov, Alyosha unifies disparate elements in the community to support a poor, sick family. Throughout Trigun, Vash similarly inspires others, most notably his friend, Wolfwood, to become their better selves in service to others. Neither story offers utopian solutions, but both model a powerful praxis of compassionate love through the daily lives of modern saints.

-

Dostoevsky, F. M. The Brothers Karamazov. Trans. Constance Garnett. New York, Lowell. Project Gutenberg. 2009. Web. 24 March 2013. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28054/28054-0.txt ↩

Arwen Spicer is a science fiction writer and lightweight academic residing in Oregon. Her novel, The Hour before Morning, has been adapted as a film due for release in summer 2013, and is running a Kickstarter campaign to fund post-production and distribution.

This makes me think of some of the other characters in Trigun and wonder how they might fit in. Particularly Wolfwood; raised by an abusive parent, whom he later shoots and kills, and his moral outlook, going back a ways to remember, being something along the lines of morality being forfeit in the face of a world that contains immoral people? Wondering what, if any, parallels you might see from him to Ivan, or any of the Brothers Karamazov.

This is really interesting, you made your point extremely effectively. Great stuff!

I would personally be more interested in the interplay between Vash and Legato. I haven’t gotten too far in the manga, but in the anime at least he was portrayed as utterly devoid of any sense of morality. Compared to Knives, who was not really present until the very end of the series, Legato actually played the role of the primary antagonist. And I think this utter lack of any sense of morality made him a suitable foil for Vash. The arc of Vash’s character development in the series really starts when Legato begins implementing his scheme and ends with him coming to terms with Legato’s death.

The Japanese are big fans of Dostoevsky, I always see his work in so much anime I watch and video games I play. Tolstoy also seems to be a big influence, but I think Dostoevsky captures the chaos and polarity between dark and light that I think just vibes with Japan and their history.