Last year, sci-fi author John Scalzi caused a minor kerfuffle in the blogosphere with his post “Straight White Male: The Lowest Difficulty Setting There Is.” In it, he argues that being born a straight-white-male in modern American society is akin to playing life on the “Easy” difficulty setting:

The default barriers for completions of quests are lower. Your leveling-up thresholds come more quickly. You automatically gain entry to some parts of the map that others have to work for. The game is easier to play, automatically, and when you need help, by default it’s easier to get.

This is, of course, not presented as a good thing. Race, gender and sexuality are all attributes forced on us by the circumstances of our birth, completely outside our control. Such an advantage violates our intuitions about what is and is not just. Scalzi’s article is not written is a condemnation of straight-white-males (SWM), but rather as a metaphor to help explain the advantage that gender/sexuality/race can have. That, of course, did not stop a number of straight-white-males from (a) feeling condemned and (b) cursing on the internet about it.

So why did it get a heated reaction? And what do video games really have to tell us about ordering a just society? And is there another John “Last-name-rhymes-with-‘shawls'” out there with something to say about it? (Spoiler Alert: There is.)

If the SWM-as-lowest-difficulty-setting argument works, it’s because it is easy to recognize as unjust. We probably wouldn’t voluntarily play an MMORPG where some people got to play on “Easy” and other people get to play on “Hard.” We wouldn’t like Starcraft if the other guy’s SCV got more crystals for every trip than ours did. If we found out that someone else WAS getting this advantage, we’d very quickly jump to the conclusion that they are cheating: the feeling of injustice is difficult to shake.

And, of course, people don’t like being told that they are the beneficiary of injustice. If you played Call of Duty for hours a day and rocketed to the top of the player rankings, you wouldn’t be happy if someone told you that the only reason you did so well was because of a glitch in the game that made your bullets do more damage than the other guys.

I think there’s an even deeper reason why this article touched such nerve with certain people. It touches on something that our own John Perich discussed in his article on Dragon’s Crown last week. Video games in the United States are, by and large, written for straight white men. This is of course a vast oversimplification; it ignores major shifts in the market, particularly in the mobile arena. That said, a quick look at the top-selling games of last year reveals a bunch of 1) sports games and 2) action games starring straight-white-males (with the occasional sexy lady for them to look at),

This is why the “video games as metaphor for privilege” metaphor cuts so deeply – because to the straight-white-male, video games are “our world.” Scalzi’s SWM metaphor is an appropriation, an invasion. Video games are the last bastion of society where anyone can be as hatefully rascist/sexist/homophobic as they want to be, without really anyone telling them otherwise. So using the rhetoric and logic of video games (dominated by SWMs) to point out real world injustice (which favors SWMs) probably isn’t going to go over to well.

But how well does the metaphor work in the other direction – are video games as unjust as the world they represent? While the “Difficulty Setting” metaphor may be a useful way of looking at injustice in the real world, it’s not a particularly accurate way of looking at the justice in video games. Video games are actually quite fair: difficulty settings in video games, generally speaking, only give the player an advantage over features of the environment and Non-Player Characters. There’s probably one out there that I don’t know about, but the vast majority of multi-player games do not have difficulty settings like the one that Scalzi uses in his article.

When it comes to comparing gaming experience between players, even the most violent, immoral and debased video game would still go to great lengths to ensure a balanced gaming experience. The “world” of the video game might be unjust in a representative sense (in that you murder and rob your way through the game), but it’s extremely just in the sense that it’s completely equal between players.

Everyone starts out at Level 1, it takes the same number of points to get from Level 1 to Level 100, and everyone gets the same number of points for killing a Were-Bear. Killing other players is either allowed or not allowed – there aren’t any servers where only one group of players is allowed to kill the other players. Fairness is baked into the system and designers strive to maintain it all costs. If one character class or weapon becomes too powerful, the game designers will act to reduce it, “Nerfing” the characters and weapons if they start to unbalance the game.

Not this kind of nerf.

Video games are governed this way because they exist only with the consent of the governed. It’s not that they’re democracies – everyone doesn’t get to vote whether or not a Lightning Bolt should do 50 hit points or 60 hit points. However, if all of a sudden the lightning bolt does 1000 times more damage than any other weapon or spell, players will surely vote with their feet. All of the challenge will go out of the game for the Mages, and players that can only swing a sword will be upset at how powerful the Mages are all of a sudden. When they set out to create a world, video game designers are forced to create a world that all of the players will consent to playing, which means it has to be fair.

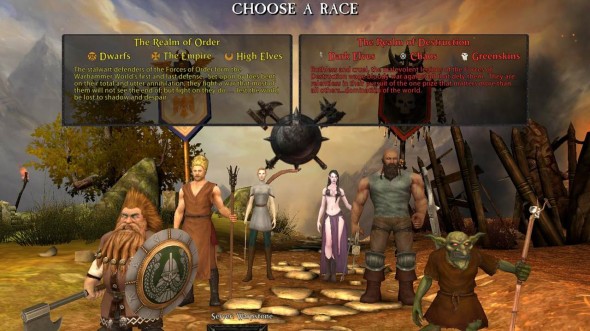

Because this is Overthinking It, we can’t quite stop there. The question of “How should we design our game” is closely paralleled by a much older question: “How should we design our society?” A good game designer is going to make a game that’s fun regardless of what team you play for. Even if a particular game designer likes to play as a Night Elf, he needs to make sure that Orcs and Humans have an equal chance of succeeding in the game. He has to essentially forget what he likes and create a game that everyone will want to play.

The same goes for societies, and that idea is older than video games. In his seminal work “A Theory of Justice”, philosopher John Rawls argues that we should create societies the same way. When we’re deciding how to order our values, we should based it on a sort of willful blindness about initial conditions.

Rawls argues that a just society is one organized along certain rules. Those rules should be written such that they would get the consent of all rational, unbiased individuals. Unfortunately, there’s no such thing as a truly “unbiased” individual, so he makes use of a thought experiment known as the “Original Position.” He imagines that all of the individuals in a society are placed behind a “Veil of Ignorance” where:

…no one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, nor does anyone know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like. I shall even assume that the parties do not know their conceptions of the good or their special psychological propensities.

If you don’t know whether you’re going to be black or white, chances are you’re going to make the rules the same, regardless of your race. If you don’t know what gender you will be, you’re going to want to make sure that the principles of justice apply equally to both sexes. Because the people in the Original Position are ignorant of their future place in society, they will endeavor to create a society that is as fair as possible. [1]

This is similar to the position that game makers find themselves in. They need to create a set of rules for a world that will be consented to by a wide range of potential customers. Game designers, though, have two advantages over would-be society builders. First, they get to define the rules of the universe entirely: if you don’t want people to be able to kill each other, you don’t have to write a rule that says “No killing”, you can just change the flag to “PlayerToPlayerDamage=False”. Second, they get to start from scratch: no baggage from previous failed attempts.

In the end, this means that the video games are far more just than anything you’d find in the real world. In a video game, the “city guards” might react when you kill someone or they might not, depending on the programming, but it probably doesn’t matter much who you kill. In the real world, the odds of the “city guards” reacting changes depending on the race of the victim. In a video game, the same quest gets you the same suit of armor. In the real world, your pay varies with your gender.

Gold farming is one of those things that make you want to quit writing science fiction because you could never come up with something that crazy. – Neal Stephenson

Admittedly, this ignores one aspect of gaming that most developers go out of their way to try and defeat: the impingement of real-world inequality on the otherwise “equal” gaming world. The ability to use real-world money to buy in-world objects has recently eroded the standard “fairness” goal of game design. A rich guy can just buy a top-level character, without doing all of the work that everyone else has to do to get there. And of course, this pisses people off. We don’t like it when our “fair” world of video gaming gets upended by the “unfair” real world.

But we can use the principles of good game design to help design a better society. Game designers have to work hard to create rules and practices that everyone can abide by, because no one will play if they don’t. You wouldn’t buy a game where the rules are always stacked in favor of one team. You wouldn’t buy a game where some players get to break the rules and others get banned. So when confronted with a problem of inequality or fairness, ask yourself, “Would I buy that game?”

-

A lot of people take serious issue with Rawls’ argument for what people would actually agree to. He uses the Original Position and Veil of Ignorance as a framework to justify capitalism and (limited) inequality of outcomes. That’s outside my mandate a bit, so I’ll just say that I think the intellectual framework is an interesting one from which we can reason. ↩