[Enjoy this guest post by Ariel Herrlich, who took Matt Belinkie’s raw data for the astoundingly thorough analysis on the age of Academy Award nominees and winners for acting awards and subjected it to an even higher level of statistical scrutiny. – Ed.]

A couple weeks ago, Matthew Belinkie wrote a great piece about the effect of age on one’s likelihood of winning an Oscar. Boldly daring to do what I had only ever fantasized about, he created a comprehensive database containing every single nominee and winner for any acting-related Academy Award along with their respective ages. His findings supported the common notion that aging actresses face limited opportunity in Hollywood, although being older can help actors and actresses earn accolades in some respects.

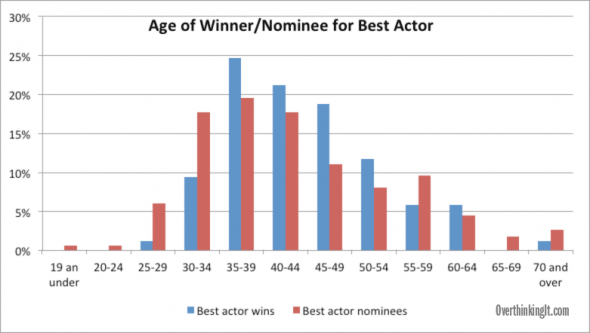

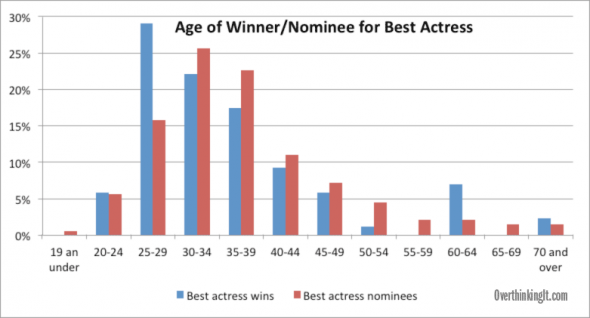

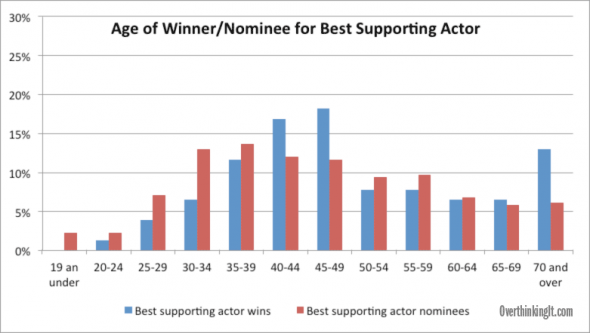

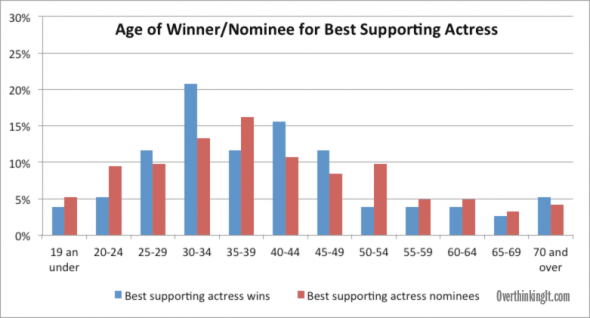

Lucky for me, the dataset used to create this work is available for public download. I hypothesized that the graphs of age by percentage of Oscar winners/nominees would look different if ages were grouped into 5 year-ranges. This allows us to observe general trends without the influence of anomalies and outliers.

Below are the results (click on the graphs for larger versions):

These graphs highlight four basic conclusions—two of which emphasize the points made in the original post, and two of which strengthen those original points with further insight.

As was concluded previously:

- If you want to win or be nominated for a best actor/actress award, it helps to be younger. For supporting acting roles, age plays less of a factor.

- In both acting categories, women who are nominated and win Academy Awards are younger than their male counterparts

The second pair of conclusions address gender discrepancy with regards to age:

- Male winners of either acting award are more likely to skew older than the rest of the nominees. For women the opposite is true: winners tend to be younger than the other nominees.

- As actresses get older, their chances of being nominated or receiving an Academy Award spiral downwards at a steeper rate than actors. This is especially true for best actress awards.

These trends do not bode well for actresses, as none are exempt from the inexorable process of aging. If the nominees of a category are all more or less of equal skill, then it is disconcerting to see that being younger also separates the winner from the rest. Although the best actor bell curve is weighted slightly heavier on the younger side, it is far more evenly distributed than the best actress curve, which peaks just as an actress is beginning to establish her career and decreases almost exponentially shortly thereafter.

For supportive acting categories, there is more flexibility in casting older (and much younger) actresses as well as actors in supporting roles. The higher proportion of older nominees and winners in this category suggests that these actors and actresses have “paid their dues” but haven’t gotten their statue yet. Although older supporting actors enjoy only somewhat more frequent nominations than older actresses, they are much more likely to win, especially when over 70. On the other hand, the Academy seems more willing to take risks in the supporting categories with younger nominees than in the leading categories. However, although supporting roles equalize age and gender somewhat, very young supporting actresses are more likely to win than very old supporting actresses, whereas the opposite is true with supporting actors.

The stark difference between leading actors and actresses is more puzzling. The women who win best actress are enormously talented, and portray deeply complex characters. Although some, such as the latest winner Jennifer Lawrence, play romantic leads in a film that is mostly about a man (other examples include Reese Witherspoon in Walk the Line, and Gwyneth Paltrow in Shakespeare in Love), many more do not. Marion Cotillard in La Vie En Rose, Natalie Portman in Black Swan, and Hillary Swank in both Million Dollar Baby and Boys Don’t Cry – these roles require serious acting chomps more so than youth and beauty.

But while acting in front of the camera may be immune to biases against women of age and appearance, Hollywood is first and foremost a business; no one wants to see a box office bust, no matter the critical acclaim. If youth and beauty isn’t a factor in front of the camera for Oscar-nominated films, it certainly still matters for press interviews and late night talk shows. Why else cast Charlize Theron as Aileen Wuornos or Nicole Kidman as Virginia Woolf? For actresses in a leading role, half the job is gussying-up and to walk the red carpet at their premiers, at Cannes, and ultimately, at the Oscars.

The sheer beauty of youth as a factor that helps young adult actresses to secure best actress or best supporting actress nominations and wins – and then works against them after age 30-35 – is a factor also tangibly present in other public-facing professions. Dr. Erika Show, who hosts a science TV show for children, was crowned Miss Massachusetts in 2004. LA mayoral candidate Wendy Greul was formerly a cheerleader. Oprah was Miss Black Tennessee in 1972. Sarah Palin was the 2nd runner-up in the 1984 Miss Alaska Pageant. Other former beauty queens turned politicians include Shelli Yonder (2nd runner-up for 1993 Miss America, running for Congress), Erica Harold (2003 Miss America winner, also running for Congress, Laura Cheape (2011 Miss Hawaii, also running for Congress, and Caroline Bright, 2010 Miss Vermont, running for Senate in Vermont. The “beauty track” is a gender-specific career booster in the formative years, a “value add” that speaks to our unconscious celebration of female young adult beauty.

Sorry to respond to this so late (I’ve been traveling a bunch) but I’m delighted you took this and ran with it. Those are some pretty-looking graphs!