In the Global War on Terror, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups. The CIA, who investigate terrorists, and Navy SEALs, who shoot them in the face. These are their stories.

A few weeks ago, we here at Overthinking It did our podcast about the Oscar-nominated Zero Dark Thirty. Pete Fenzel and I were clearly in disagreement over the relative merits of the film. I enjoyed it (with some reservations), while he clearly had serious issues with the way it portrayed American power and the use of torture specifically. I struggled a bit to explain exactly what I liked and didn’t like about the film. I couldn’t quite put my finger on the “Why” of a project like Zero Dark Thirty: why this movie in this way.

I started with a rejection of the theory that Zero Dark Thirty is just a straightforward retelling of the hunt for Osama bin Laden. The movie opens with a 25-minute sequence centered around the brutal interrogation of a detainee. Even aside from the political controversy they created, these scenes color the entire artistic project. The entire movie is not about torture, but it’s hard to shake those images. That said, torture had ultimately very little to do with the actual success or failure of the hunt for bin Laden. As the movie itself admits, the crucial piece of intelligence came from tricking the detainee, not (directly) from torture. A film that strove to just “tell the story” would have no need for long, lingering shots of a detainee being waterboarded.

I also rejected the theory that the movie can be described in more general terms as a “war on terror” story that aims to capture the post 9/11 “experience” as a whole. While that would explain the inclusion of the torture scenes, it doesn’t explain the exclusion of a crucial chapter in the history of the War on Terror – the invasion of Iraq. For better or worse, you can not understand the American response to 9/11 without talking about the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Massive resources (of both blood and treasure) were pulled off the hunt for Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and poured into the invasion and occupation of Iraq. Zero Dark Thirty, on the other hand, essentially ignores this – the war is mentioned only briefly and in passing.

So I started thinking about one thing that stood out to me in the final act of the movie. The last act of Zero Dark Thirty is a 40-minute portrayal of the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan. The raid is masterfully directed and staged – despite knowing what’s going to happen, it has you on the edge of your seat. I’d compare it to Apollo 13 in that regard – I have seen that movie dozens of times, but still get a bit nervous that this time the parachutes won’t open upon reentry.

That said, the film spends a seemingly inordinate amount of time on a rather mundane task: opening doors. Blowing up or knocking down doors, (“breaching”), takes up a huge amount of screen time. It stuck out to me in part because of my personal experience – I am by no measure whatsoever a Navy SEAL, but have some limited training in the breaching tactics associated with boarding ships. So when the SEALs yell “Breacher!” my ears perked up a bit. (Though they would not have yelled anything in the actual raid – hand signals would suffice).

Aside from that, it’s still remarkable how much time is spent on such a mundane task. At several points in the film, the entire raid is held up while the SEALs figure out the best way to knock down a door. This is of course entirely realistic, but interesting nonetheless. In most action movies, opening doors is taken for granted – even in the rare instance that a door is locked, our hero can just kick really hard and down it goes.

I could only think of one other genre of entertainment where the opening of a door is so important to the story telling – video games. In the Zelda games, for instance, the “boss door” is frequently right there at the beginning of the dungeon. You know where to go and you frequently even know what you’re going to find when you get there. You just don’t know how to open the damned door. I was reminded of Josh McNeil’s article about the “Well Made Video Game Plot” and his categorization of stories into “Whodunnit”, “Whydunnit” and “Whendunnit”.

BREACHER!!!

Zero Dark Thirty is not a whodunit – we know who is going to die (bin Laden), who is going to find him (Maya) and who is going to kill him (Navy SEALs). It’s not a “whydunnit” – we don’t really have a sense at any point for what motivates the characters in their hunt. As discussed above, Zero Dark Thirty’s liberal handling of the truth means it’s not really even about what was done. Rather, it tells the story of how this sort of thing is done.

In this sense, Zero Dark Thirty is really just a procedural. We know what’s going to happen and who it’s going to happen to, but we don’t know exactly how it is done. It’s really just a “Ripped from the Headlines” episode of Law and Order. I’m of course not the first to make this observation, but it’s worth going discussing just how deeply the structure of Zero Dark Thirty resembles a typical episode of Law and Order.

First of all, as I alluded to above, the structure of the film is similar. As the title suggests, Law and Order is always neatly divided between “Order” (finding the bad guys) and “Law” (punishing the bad guys). Zero Dark Thirty is not quite as equitable in terms of screen time, but it is just as clearly divided up into finding the bad guy (the CIA) and then killing him (Navy SEALs).

Second, the characterization is similar. Law and Order is famous for being extremely sparse with personal details about the cops and prosecutors that are the main characters – the history of Lenny Briscoe and Jack McCoy are elided and mentioned in passing, but we never see them at home. Every once in a while we see them at a bar, talking shop with a whiskey in hand. Similarly, Jessica Chastain’s “Maya” is a cipher – we get a few details here and there and she socializes with a colleague, but the mission is always front and center. For a procedural, the institutional role is what matters, not the person behind it.

I’d rather have the Navy SEALs after me.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the two are similar thematically. While L&O was firmly in the pro-police-and-prosecutor-camp, the show was also not shy about showing some of the messier aspects of the legal process. Briscoe was known to twist a few arms and Jack McCoy was never shy about using trickery and deceit to get the desired outcome, often skirting or crossing the lines we might expect them to follow. Zero Dark’s torture scenes fit this mold as well – while we’re clearly meant to root for the CIA, the movie is not meant to make us entirely comfortable with everything that is done in the name of our protection. L&O and Zero Dark Thirty share a common theme – these are the things that happen in the name of law, order and security, and they are being done on your behalf and in your name.

When L&O has a “ripped from the headlines” episode, we’re not concerned with whether or not that’s really what happened in a given case, but rather whether or not that’s really the kind of thing that cops and prosecutors do in a high profile case. Zero Dark Thirty isn’t striving to be 100% true to the events it portrays. Rather, what’s important is the “truthiness” of the film – that it accurately portrays the kind of events being shown. We don’t care whether or not that particular door in bin Laden’s compound actually needed to be breached, but we are meant to understand that locked doors are part of the process – just like we’re meant to understand that witnesses change their minds on the stand and judges suppress evidence.

And as a procedural, Zero Dark Thirty is a masterpiece of truthiness. The torture sequences are included not to show that torture was necessary to find bin Laden, but to show that torture was done, in exactly the same way that L&O shows Briscoe and Green sidestepping the warrant requirement to search the apartment of the suspect (even though it turned out to be the husband the whole time.)

Zero Dark Thirty is even true to the bureaucracy that’s involved – the days upon days it took the make a decision to attack. It shows that the last piece of the puzzle was under the CIA’s nose the whole time, found by a brand new agent looking through old files – a common occurrence in the world of intelligence. To borrow a phrase from Mr. Fenzel, the real world of intelligence is sometimes just about “getting pissy and filling out forms.”

Like L&O, Zero Dark Thirty shows that the “Law” and “Order” sides of the house have different priorities. While the cops may only be concerned with getting the bad guy, the prosecutors have bigger concerns of due process and the law to worry about. Similarly, Maya and the SEALs are differentiated in their goals and methods. When bin Laden’s body is brought back to the SEALs base camp, Maya, who has been single-mindedly hunting the man for years, can do nothing but stare at the body bag. The SEALs, who have “been on this mission before,” are already focusing on the next task, collating intelligence found in the compound.

What’s interesting is that Zero Dark Thirty is not the only movie about history, or even the only historical procedural at the Oscars this year – both Argo and Lincoln are fundamentally concerned with events whose outcomes are known. There’s no doubt going into Lincoln that the 13th Amendment is going to be passed – what’s interesting to the audience is what Lincoln has to do to get the job done. Similar to Zero Dark Thirty, we fully support the goal that the protagonist is trying to achieve – killing bin Laden or freeing the slaves – but we are also left with questions about the moral compromises that have to be made along the way. Lincoln has to essentially bribe Congressmen to get the votes he wants, and Thaddeus Stevens has to compromise his deeply held principles on the House floor. All of this is done for a goal we support, but we are not necessarily meant to be fully satisfied with the means used to bring about the end.

This brings us to another concept that came up on the podcast. Pete Fenzel posited that Zero Dark Thirty was too realistic – that because it was accurate in so many of the details, the creative license taken by the filmmakers are likely to get swallowed up in the minds of the audience. The focus on breaching doors and a minute-by-minute telling of the raid obscures significant liberties with the truth. Real people with real families are portrayed, but shown in a negative or incompetent light that doesn’t match up in any way with reality.

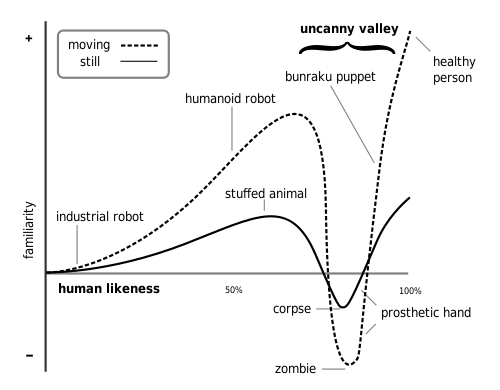

This led us to the idea of an “Uncanny Valley” of historical fiction – that if an artist portrays an event that is almost accurate, but not quite, it can actually be worse than if the film hadn’t bothered with accuracy to begin with. The audience should be able to tell that what they are seeing is a story. The phrase “ripped from the headlines” does a great job of this – Law and Order never made their “real life” episodes in such a way that led you to believe it was really what happened. Rather, L&O was all about the way that institutions behave when faced with these real-life dilemmas. It was firmly on the left side of the uncanny valley, while still being far enough to the right to be informative.

Argo is probably far enough from the truth to avoid this trap – the car chase at the end is a dead giveaway that liberties have been taken. In Lincoln, the liberties are less obvious, but the distance from the source material and intimate conversations between Lincoln and his family make clear to the audience that the film might be “truthy”, but it’s not true.

The best illustration of this principle is yet another Oscar nominee – Django Unchained. Like a hand-drawn caricature portrait, we’re never under any illusion that the events of the film are even close to what happened, but that’s not the aim of the film. A caricature can be even more recognizable than the most photo-realistic portrait because it emphasizes certain recognizable features. Django is an inversion of films like Zero Dark, Argo and Lincoln – instead of showing how things happened without taking a position on whether or not it was good or bad, Django uses a story of what didn’t happen to take a more forceful moral stance.

Ultimately, I think it’s hard to tell exactly whether Zero Dark Thirty falls into the Uncanny Valley or not. From the opening title card to the exquisite attention to the intricacies of door breaching, Zero Dark Thirty tries it’s best to make you forget that what you’re watching is not actually footage from Abbotabad. It’s often successful in this regard – it’s sometimes hard to convince your brain when you’re watching it that those are just actors on a set. The film is a top-notch detective thriller and an edge-of-your-seat thriller. But the people involved are real, and it’s at least a little worrisome how easy it is to forget that fact.

Dear Ben Adams,

You should not be using your time more effectively. Instead, you should just wax on and on about movies and TV shows.

LOVE the idea of using the Uncanny Valley to discuss naturalism in historical fiction. It kinda of drives me up the wall when people assume that all historical fiction must be completely accurate in every respect. As you say, it would be absurd to judge Django Unchained against Lincoln, even though both ostensibly take place in roughly the same era. Not that you can’t criticize the way Django takes liberties with the truth — but if you slam it because, say, Leonardo DiCaprio’s belt is more 1870s than 1850s, you are missing the damn point!

In case you’re wondering: yes, I take this issue a little personally. (Historical fantasy represent!)

In my more cynical moments (ie. most of the time), due to how badly I judge the average American education, I do wonder how many people take what happens in movies like this as portraying what actually happened.

How many people think what happened in Black Hawk Down is 100% accurate? How many people think Americans really were the ones who got the coding machine in U-571? Or that the bomb was used only because of Pearl Harbour?

And now we have this neat narrative telling of how Osama was taken out.

People are seeing a movie, but all too often I get scared that people are watching a documentary.

What stuck out to me most when reading this article is the fact that, when referencing the cops from Law & Order, you went with Briscoe and Green. Why that choice? Why not Briscoe and Benjamin Bratt? This is what I was supposed to take away from this article, right?

I’ve also pondered the truth in moviemaking thing often, and it’s gotten to the point where I don’t assume what I am being told is true except in the vaguest of senses, and then I delve into the historical fact afterwards. I am helped by the fact that after I watch any movie, even if I dislike it immensely, I always read about it on the internets because film is interesting.

Obviously, there is a practical purpose for why this is done, because movies are trying to entertain, so sometimes excitement, or romance, or drama, or what have you need to be added. They gave Russell Crowe’s character a kid in American Gangster and had a whole custody battle thing going on, which wasn’t the case in real life, and I was perplexed by that after watching the movie, because it was fairly significant, but I suppose they felt they needed to give the character depth and make him more vulnerable and such. My prevailing feeling is, as long as they don’t egregiously change a real person’s personality, which is to say turning a decent person into a monster or vice versa, I’m cool with it.

Of course, this seems to mostly be an issue with drama. I don’t recall this ever really coming up in comedy. Sure, there are less comedies based on true stories, but they do exist, and I suppose for the sake of humor more stretches of the truth are accepted. Additionally, it is often more clear in comedies when something isn’t true, because the absurdity of what is being posited is in and of itself a joke. People tend to be find with that, which is good for my current dream project of a TV show in the style of the Adam West Batman but with Richard Nixon as the masked superhero.

Also, as I have seen another person with the audacity to share my exceedingly common first name commenting on the ol’ OTI webpages, I suppose now I have to go by my full name to protect my reputation as a bon vivant and man of letters. Unless the Chris Morgan who wrote some of the Fast and the Furious movies starts reading this website. Lastly, nobody cares and I don’t know why I bothered bringing this up since it is pretty self-evident.

On the matter of historical accuracy, I am reminded of the introduction to “1066 And All That” by W.C. Sellar and R.J. Yeatman. The entire (and completely hilarious) book is based on their position that History is not a record of what actually happened, but what we _remember_ to have happened….

What we as the audience need to keep in mind is that movies are not always documentaries. They are made to entertain, not educate, and certain liberties with accuracy are to be expected (though not always condoned).

I like this article a lot. The ultimate reason I had to give up on Law and Order was the liberties the police (and really McCoy) took with the law. And I eventually found it frustrating because they were, in fact, never wrong… so when they took those liberties, it always worked out in the end because the bad guy got punished. I always wanted some case where Briscoe or McCoy did shady things to put someone away when we, as the audience, knew they were wrong and should question the ultimate procedural trope of “cop’s gut.” Because that happens, too, and people should know about it.

Similar here with the torture in this case. 24 spent 8 years asking television fans exactly how far they’re comfortable with going to get this kind of information in the course of a live, unfolding investigation.

The more I think about zero dark thirty, the more I get annoyed with it. The movie can’t decide what it wants to be. Originally I would have agreed with Ben’s article, but the more I think about the film and the historical context, the more I get frustrated.

The problem is that, as far as we know torture was not used to find Bin Laden. Whereas with the film what we tend to get is a lot of violent torture and horrible things ensuing. The director of the CIA screaming, “give me someone to kill” comes off as some kind of harsh satire rather than serious discussion. The meetings at Langley come off as particular satire because of the ridiculous lies and double talk sued by Bush’s administration.

It would be one thing for the movie to come off as a documentation of ‘the price we paid to kill Bin Laden’ and of the kind of horrible things the US did, but that would be an epic of all the horrible things that have occurred for the last decade but the movie treats its characters as heroes; even Dan, who opens the movie by waterboarding a guy.

When the US people learned of the king of horrible things going on in Abu Gareb and Guantanamo there was a disturbing feeling in America that we are becoming the kind of tyrannical, horrible things we have tried to fight for years. America has killed countless numbers of people in the war against error and the drone strikes we implement still continue to slaughter innocents.

Does the director really think that the pain, the horrible, physical pain, induced by our agents is the kind of thing that actually works to get the results we desire? Whether for revenge or justice or other motives, the use of torture has been proved to be useless time and time again and all we do is just hurt innocents through our methods.

Usually I’m not one for taking a stance on torture; as I have a heavy, heavy hatred for terrorists, but in the particular case of making a point for it via convoluted morals in a historical fiction, is just too confounding.

The directors seem to think that their movie does not promote torture. Following the lengthy chain of logic of the film, with the first piece of information obtained via scaring the hell out of a prisoner to the point where he really does not want to be tortured again and then following through the steps of other interrogations to gain similar clues, the movie does actually show that the violence perpetrated by our agents was used to find Bin Laden.

And even at that the movie should mean nothing. Al Quaeda is still active and the Arab world is still rampant with violence and destruction. There are no heroics in this film, but the movie would like to pretend it’s a Tom Clancy novel.

The movie confuses its morals and themes with the actually history and then confuses itself again.

Just want to point out that although the torture itself didn’t elicit the “crucial piece of intelligence”, the trickery was unlikely to occur without the conditioning that occurred during the waterboarding. The detainee WANTED to believe that these people were his friends. Because then telling them what they wanted was justified in his eyes.