This week, the YA world is abuzz about The Madman’s Daughter, a new piece of historical fiction about the teenage daughter of Dr. Moreau. (Yes, that one.) (Yes, there is a love triangle in it.)

This week, the YA world is abuzz about The Madman’s Daughter, a new piece of historical fiction about the teenage daughter of Dr. Moreau. (Yes, that one.) (Yes, there is a love triangle in it.)

When I first got wind of the title, my mind immediately went back to one of the very first articles I ever wrote for OverthinkingIt.com. (Don’t read it. It’s meh.) In that piece, “The Unoriginal Writer’s Daughter,” I took writers – mainly women writers – to task for continually naming their books The Such-and-Such’s Wife and The Such-and-Such’s Daughter. A quick jaunt over to Amazon will show you that this trend is still very much in play today.

However, today I’m not going to criticize. I know how hard coming up with a title is. My publisher and I went through a list of maybe 50 titles before settling on Hammer of Witches, a name called “cool” by some and “huh?” by others. (It makes sense in context.)

Instead of criticizing, I’m here today to quantify and analyze. In other words: overthink! And, as is true in every good overthink, There Will Be Charts. My big questions for today are

- Which family members get it the worst? Are there more daughters, sons, wives, husbands, mothers, or fathers in these titles?

- Are these titles more common in certain genres of literature?

- Do certain genders get this sort of title more than others? Put another way: is there sexism afoot?

- Is The Such-and-Such’s Family Member really that common a title anyway?

Let’s find out!

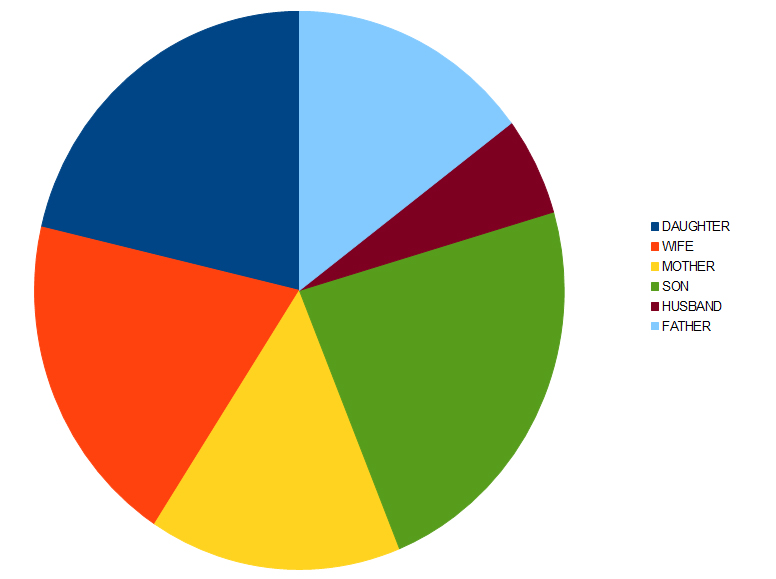

1. Which family members get it the worst? Are there more daughters, sons, wives, husbands, mothers or fathers in these titles?

To answer this question, I hopped over to Amazon and did some simple searching. To make things easier for myself, I limited the searches to all works of fiction released after April 2008, which was when I wrote my last Overthinking It article on this subject. Here’s what I found:

As suspected, there are lots of daughters and wives in fiction titles, but there some fathers and mothers, too. Most surprisingly, there are a ton of sons – you can see “sons” has the highest share of the above pie.

Okay, easy-peasy. Now let’s move on to the more difficult and I think more interesting questions.

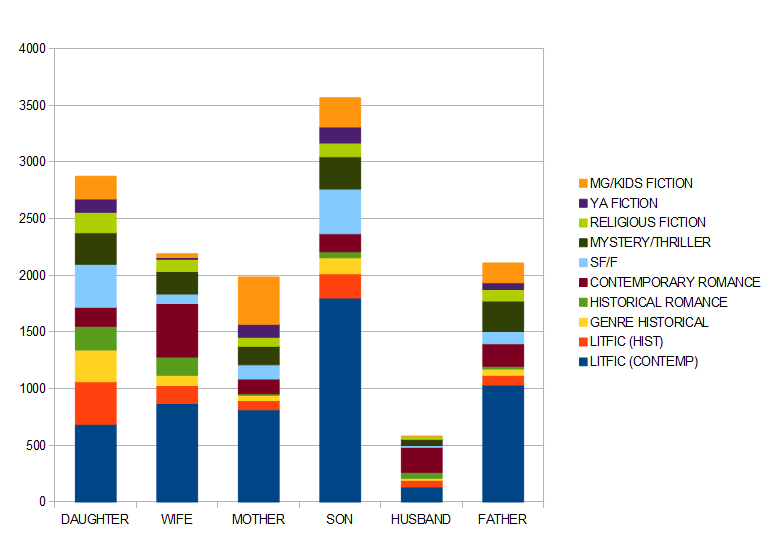

2. Are these titles more common in certain genres of literature?

To answer these questions, I had to get my hands dirty with some advanced searching. The following data won’t be super-scientific, because Amazon doesn’t categorize its literature perfectly – I’ve found non-fiction in fiction genres and Harlequin romances in “literary fiction” – and there’s a bit of overlap between genres. For example, if The Madman’s Daughter were not YA but an adult book, it would be slotted in under “Horror,” “Historical Fiction,” and possibly “Romance” and “Literary Fiction.” I tried my best to separate different genres – you’ll notice when you look at the following graph that I separated regular historical fiction from literary historical fiction and romance-historicals as best as I could.

First, the raw numbers:

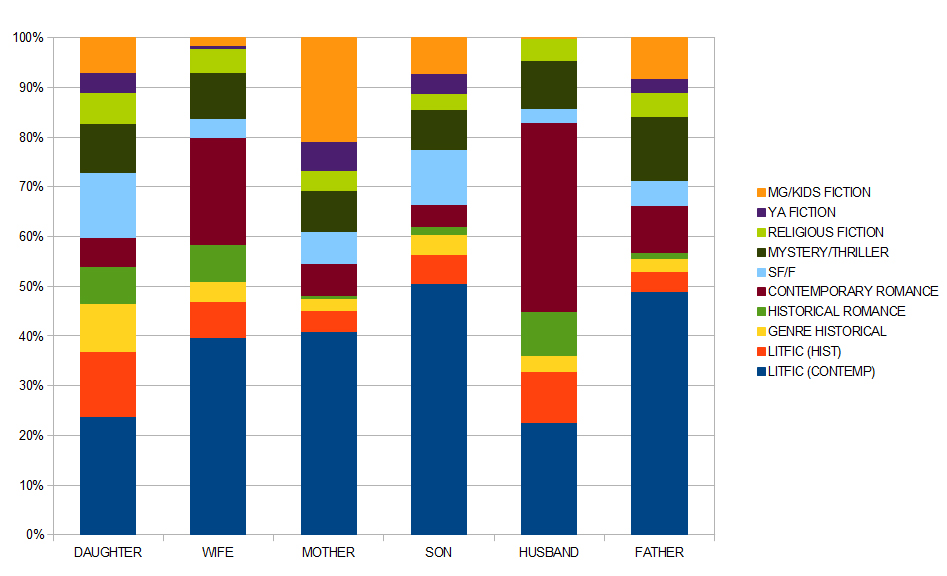

Next, the percentages:

You can see that family-based titles are extremely popular in literary fiction, which might be why many of us get the impression that these titles are more popular than they actually are. Literary fiction is the kind of fiction that gets the Pulitzer Prize, the Man Booker, the prestige film that doesn’t actually do very well at the Oscars. I’m sure if you think for a second you can easily come up with the name of at least one big award-winner or Oprah book that has the name of some family member in the title.

My theory going into this article was that these titles would be very popular in historical fiction, too. I was wrong, sort of. If you look at the percentage graph and look at all the historical bars (the orange, yellow, and apple green ones), you’ll see that only “daughter” was really big in the historical field. The husbands got some play in the historicals, too, but if you look at the raw numbers above you’ll see that there are very few husbands in titles in general.

Husbands were more likely to be seen in romances, just like wives, which is probably not too surprising seeing as the words “husband” and “wife” have to do with romance (or at least sex and hot hot paperwork).

Mothers were quite popular in kids’ books, although this number is inflated by the ubiquity of Mother Goose books. There were also more mothers than fathers in YA titles, which likely reflects the fact that most YA readers are women and girls.

Something that surprised me but made a lot of sense when I thought about it: daughters and sons were featured relatively frequently in science-fiction and fantasy. In these cases, the titles tended to be along the lines of Daughter of Time: A Time Travel Romance and Son of Eden. We’ll talk more about the significance of this type of title in a sec.

3. Do certain genders get this sort of title more than others? Is there sexism afoot?

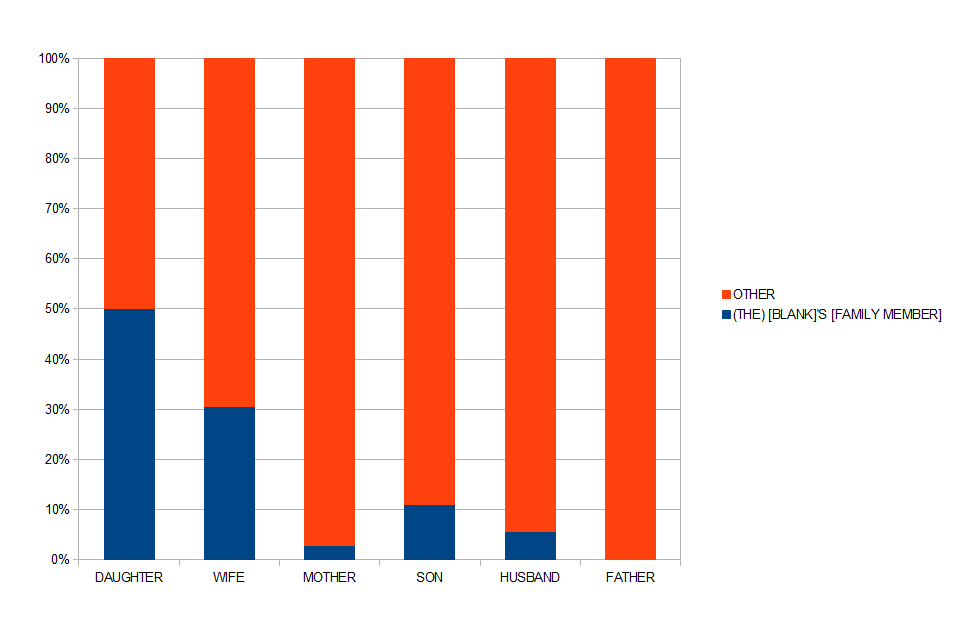

To answer this question, I took a small sampling of titles from the first 3 pages of fiction within each search. So I typed in “fiction” for topic and “daughter” for title and analyzed the first 36 titles that popped up (not including same-named sequels). I first counted all titles that followed the format (The) [Blank]’s [Family Member]. “The” is in parentheses here, because I also counted books without the definite article (Pharoah’s Son, for instance). The “blank” stands for some occupation or proper noun, and “family member” stands for a family member like “wife,” “daughter,” etc. Examples include The Vampire Hunter’s Daughter, The Witch Doctor’s Wife, Liberty’s Son, The Forest Ranger’s Husband, and The Rabbi’s Mother.

As you can see, daughters get the worst. My hunch was right: The [Blank]’s Daughter is the most popular, followed by The [Blank]’s Wife. The two parents got almost no action in this template (just one The [Blank]’s Mother and no The [Blank]’s Fathers). Husbands also weren’t popular in this kind of title. If you peruse Amazon, you’ll see that most “husband” books have a female protagonist, not a male one. These books aren’t about the husbands. They are about getting the husbands (or getting revenge on them).

Interestingly, there were few sons in this kind of title. As mentioned above, sons are the most popular family members in fiction titles, but those titles are almost never The [Blank]’s Son.

The reason for this is that “son” tends to be popular in [Family Member] of [Blank] titles like the aforementioned Son of Eden. In fact, 8 of the 36 son titles I looked at followed this form. That’s 22%, not minor. In almost all of these titles, the “blanks” stood for a place, as in Augustus: Son of Rome, or a concept, as in Sons of Encouragement and Sons of Blood. Where the blank stood for a name, it was never the name of the son’s actual, physical father. Instead it was a symbolic name, as in Sons of Cain.

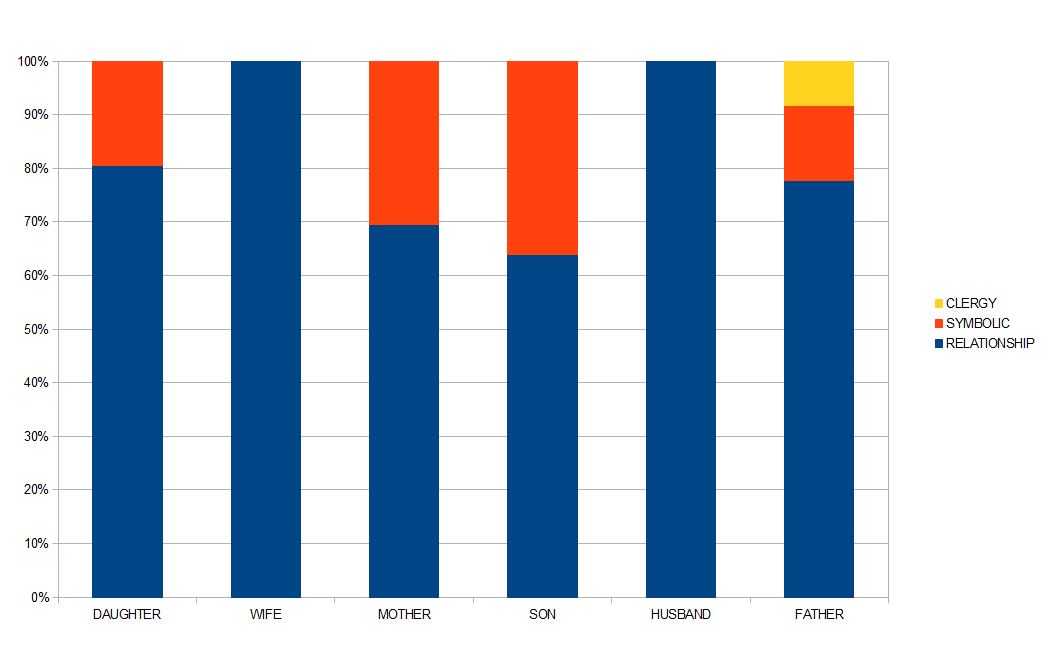

When I noticed that, I began to wonder if the female family members in titles were more likely to be envisioned as part of a relationship with another person, while the male family members were more likely to be heroic or evil archetypes. To see, I counted up the number of “relationship” titles and “symbolic” titles.

Some examples of “relationship” titles:

The Quilter’s Son (he’s only important because he is related to the quilter)

Mozart’s Wife (she’s only important because she’s related to Mozart)

The Traitor’s Daughter (she’s not the traitor; she’s just the less interesting offspring)

Some examples of symbolic titles:

Daughter of the Sea (she’s not really related to the sea)

Sins of the Fathers

Mother Earth

Liberty’s Son

I also found I had to make a separate column for “clergy,” because there were a significant number of titles that used “Father” in the ecclesiastical sense. These I couldn’t really count as either relationship titles or symbolic titles. In these cases, the “father” was actually the protagonist, and “father” was part of his name.

So:

In fact, one gender is not more likely to be “relationshipped” than the other. As a matter of fact, the numbers came out almost equal for the two genders. Husbands and wives were both considered relationship fodder 100% of the time in my small sample. Sons and mothers were most likely to be symbolic. Daughters and sons tended to be in symbolic titles when they were in science-fiction/fantasy books, I guess because in comparison to galaxies and elves, we humans are pretty young. Someone less charitable toward the speculative fictions might say it’s because SF/F tends to be more childish. (To which I stick out my tongue and say, “So?!”) If we have to say one thing about gender, it’s that daughters are a bit more likely to be defined by their relationships than sons, which is, as we say in the literary world, poopy.

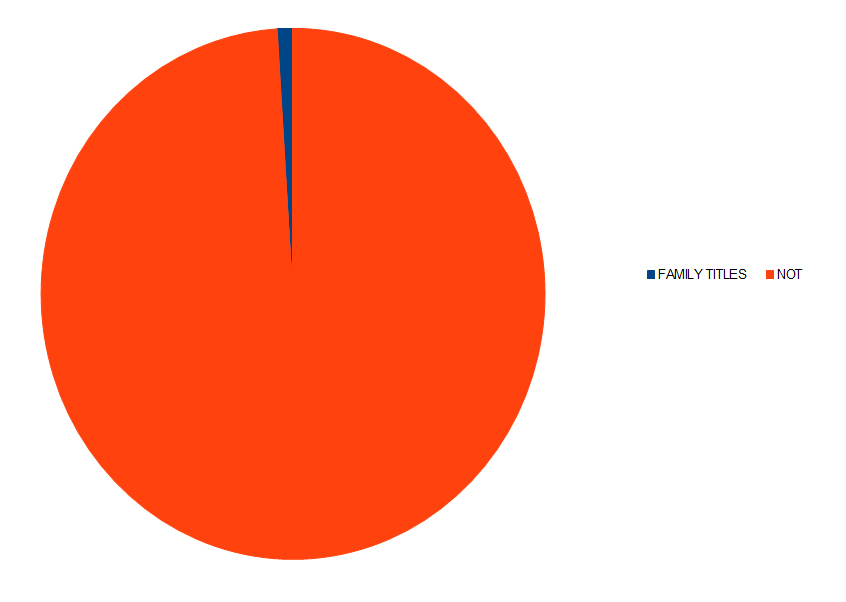

4. Is The Such-and-Such’s Family Member really that common a title anyway?

Ultimately, family-based titles aren’t as popular as we think. Though it may seem that every other book is named The Such-and-Such’s Wife or Son of the Cool Thing, they make up only slightly more than 1% of the 1.7 million works of fiction released on Amazon since April 2008. Here’s a graph:

That said, slightly more than 1% is still more than 20,000 books in only five years. So although I’m not about to criticize writers and publishers for being unoriginal with their titles, I can’t really argue if you decide to.

Do you think today’s book titles are too unoriginal? Sound off below in the comments!

Seems like I’ve seen fewer women on the internet using “JanesMom” or “Brent’sGirl” for email addresses or internet handles. But you rarely saw “I-define-myself-in-terms-of-my-girlfriend-or-children” theme in male handles. I assumed there was some internalized sexism in that, women traditionally being told that their most important roles in life are as mother or wife or girlfriend.

If we’re looking for men who do something similar, “Abu” means “father of” in Arabic, and is widely used as a traditional nickname. Usually refers to the eldest son. (Maybe “nickname” doesn’t convey the seriousness of it though.) Mahmoud Abbas goes by “Abu Mazen”, father of Mazen. Now that I look into it a little more, apparently men and women both do this, “Umm Mazen” meaning Mother of Mazen, but maybe we don’t hear it as much because we don’t hear about many famous Arabic women.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunya_%28Arabic%29

When I created an AppleID for my then 10yo daughter, who was below the 13yo limit Apple and many others impose on kids who want accounts, I called it [email protected] (neither her real name nor domain) in order to get around the system.

I suspect if you really wanted to root at a gendered difference in the relationship titles, it wouldn’t be in the title character, but in the character the title character is being related to. By far the smallest grouping is “husband”, and I would guess that’s because the “related character” is usually straight and male and therefore unlikely to be married to a dude.

This makes an intuitive sense to me. Most books entitled “The X’s Y”, in my experience have Y as the protagonist, and therefore inherently important to the story. It’s the X character who needs to have some sort of “objective” significance outside the story, and that’s going to be easier to sell with a male character, for a variety of reasons.

I could be wrong but don’t most names the begin with “Mac” or end in “son” have their roots in “son of…so-and-so”?

I feel as though I’ve seen/heard of quite a lot of books with “Confessions of” titles.

ugh.

I have nothing insightful to say. I just want to point out that I wish the book that served as the jumping off point was called “Madman Across the Daughter.” I know it doesn’t make sense, but the kids love Elton John, and they don’t mind Bernie Taupin either.

Also, I have sold a TV pilot inspired by your novel. In this show, two warlocks are having trouble getting work because everybody is hiring witches instead. There is a war on warlocks you could say (and I encourage you to, because it will feature prominently into the advertisements). So, they decide to dress like witches in over to get work and hilarity ensues. Obviously, it is called Man Witch, and we’ve already gotten the Manwich people on board as a sponsor.

The most important thing is that instead of using this comment section to further conversation on this article I have used it as a forum for my own jokes.

Fox would love it!

Also: http://youtu.be/cCuuGNc96lw

Obviously, this would be work that requires more time than a reasonable person would have (Even an Overthinking It Writer) but I’d be curious to see how often the protagonist is the family member verses the other person named. You mentioned that “The ____’s Husband” tended to focus on the wives – I wonder if there’s still some inherent sexism there, as we’re still defining the female protagonist by her man. Are there any “The ______’s Wife/Daughter” titles that focus on the male? Are books with female protagonists more likely to define their relationships in the title? Or am I just looking for misogyny in all the wrong places?

I’d be interested to know the answers to those questions, too. See, this is why we need to get better at training monkeys to do data collection for us. Get crackin’, scientists!

One can never look for misogyny in the wrong places. The patriarchy… It’s everywhere. *spooky ghost sounds*

My theory behind all these Occupation’s Female Relative titles is that the female protagonist is able to do what she does precisely because of her relationship to the male…she has some special knowledge or access to certain things that the average person wouldn’t.

OK, I may be stating the obvious here (but when has that ever stopped me before), but why didn’t you use “So-and-so’s BROTHER” or “So-and-so’s SISTER”? It seemed like a familial relationship that was missing to me as I read this.

I think it would actually be interesting to track this trend over time. I’m sure there’s a literary database of titles you could use to do a search. Have people always tried to launch new titles on the success of established properties or even begun novels based on an assumed relationship between the protagonist of the novel and the person that you assume would be the protagonist of the novel? Or, has this been a more recent move (up to a few decades old) that reflects a change in which authors are being published and the kinds of books they get to produce? What I’m saying is, are we getting more “daughters of” and “wives of” now that the people who find those stories more compelling have an easier time getting their stories published (for whatever reason).

Yeah, I was thinking about looking at sisters and brothers, too. Why didn’t I? Time. Maybe one day!

It really would be interesting to look at how this trend has changed over time. If you do it, send it over to OTI. I’d love to see it.

“Hammer of Witches” is an excellent title and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Malleus Maleficarum!

Thanks, Tice with a J! Latin 4-eva!