Blanket Spoiler Alert for The Avengers and The Dark Knight Rises. If you have not seen these movies, this article will ruin your blanket. You have been warned.

The summer of 2012 saw the premiere of two major superhero movies: The Avengers and The Dark Knight Rises. Of course, both being superhero movies it’s only logical that they would have a certain number of things in common – tropes of the genre that make it what it is instead of, you know, something else. There were plenty of extra-diegetic similarities as well: both were directed and co-written by well-respected auteurs (Joss Whedon and Christopher Nolan respectively), both were the culmination of film series that had led up to these as their climax (in DKR’s case it was the final volume in Nolan’s trilogy that started with 2005’s Batman Begins; with Avengers it was the ultimate assembly of characters and plotlines that had been being pieced together since Iron Man in 2008).

But one major correspondence between the two blockbusters is also either a baffling coincidence or an incredible synchronicity (or both): they each have the same damn ending.

So that’s weird. And it hasn’t gone uncommented upon. How could it? However, it seems to me that by comparing and contrasting the nearly-but-not-quite-identical third acts of the two movies, we can gain some fascinating insight into not just how Iron Man and Batman differ as humans and as heroes, but also some of the fundamental oppositions between the thematic and ideological divergences of the two franchises as a whole.

What happens is this: in both Avengers and Dark Knight Rises, there’s a nuclear bomb threatening the city (in the former it’s New York; in the latter, Gotham). In both movies, the hero, a multibillionaire industrialist empowered with absurdly futuristic equipment (Iron Man and Batman respectively – I’m going to be using the word “respectively” a lot in this article, aren’t I?), uses their rocket-powered technology to fly the bomb away from the city and save the lives of millions of people. In both, the hero is apparently killed in this act, but actually survives.

It’s a pretty remarkable resemblance. And it definitely says something about the nature of superheroes tropes and what we want and expect from our society’s protectors. More interesting, though, at least to me, are the ways in which these very alike denouements diverge.

First of all are the origins of the nuclear devices in question. In DKR, it’s created from a fusion reactor that was developed by Wayne Industries to be a source of clean and near-limitless energy; when Bruce realizes that it could – and likely would – end up being used as a weapon, he shut down the project, but, of course, it nevertheless ends up in the hands of the evil Bane, who predictably does intend to use it to destroy Gotham. On the other hand, in Avengers the threat is from a missile launched at New York by the United States’ government; the government believes that the Avengers have failed to thwart the alien invasion currently occurring and hope that the bomb – though they know it will kill millions – will also destroy the mystical portal being used by the aliens to attack Earth.

The very disparate causes of the nuclear threats in these cases speak to the opposing attitudes these films have toward notions of authority. DKR has been largely seen as a not-particularly-veiled critique of the Occupy movement and its perceived indiscriminate rejection of authority and laying the blame for their ill-defined problems on the so-called “one percent.” In DKR, Batman has restored order to Gotham City by sacrificing his reputation to the memory of the deceased Harvey Dent and cleansing the police force of corruption by the resulting ascent of archetypal Good Cop Jim Gordon. That is, in DKR the police are decidedly the good guys, Batman’s army representing the forces of order. The bad guys, led by juiced-up anarchist Bane, his legion of chaos, are Gotham’s own citizens. The ninety-nine percent become Bane’s willing executioners, joyfully turning the city into Ayn Rand’s worst nightmare and unwittingly allowing Bane to gain everything he needs in order to destroy them.

But in Avengers the situation is very different. It’s the government itself that turns its might against its own citizens – for utilitarian reasons and not malicious ones, they decide they need to sacrifice New York to save the entire rest of the planet – but it’s because they’ve lost faith in the Avengers that they themselves assembled under the auspices of Nick Fury’s arms-length military organization S.H.I.E.L.D. The attitude toward authority in Avengers is ambivalent at best; the Avengers are recruited (mostly) willingly, and share in S.H.I.E.L.D.’s and the U.S. governments goals, but S.H.I.E.L.D.’s agents’ willingness to lie to the Avengers in order to achieve their goals is a blow to the already-precarious level of trust that the heroes have for the whole operation. Besides Captain America, the Avengers are all civilians and have very different ideas of what is necessary and what is permissible when it comes to protecting the homeland – or in this case, the home planet.

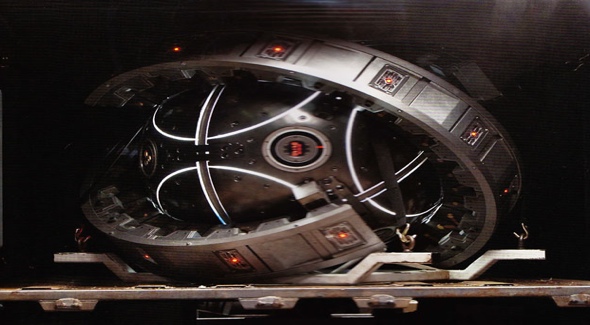

The attitude toward power in both films is investigated by means of a thematic pun – “power” functions both in the sense of authority and in the sense of electricity. Both Avengers and Dark Knight Rises include objects that are intended to provide unlimited cheap electricity: Bruce Wayne’s fusion reactor and the Tesseract which serves as Avengers’ MacGuffin, the object that both S.H.I.E.L.D. and Loki want to obtain in order to achieve their goals. What bears scrutiny is the fact that in DKR, Bruce Wayne himself stops all research into the fusion reactor due to the risks, despite its potential for benefit, and yet the continued existence of the reactor does in fact lead to the nuclear threat at the climax of the movie. Whereas the Tesseract never poses any such threat; the U.S. government, in that case, genuinely does want to use the Tesseract for peaceful purposes, but also wants to use it to create weapons, and the fact that the Avengers have been lied to about the government’s secondary, destructive purpose in their quest for the Tesseract is what causes the heroes to rethink their relationship with the authorities. But not only is the argument in favor of weaponizing the Tesseract actually pretty convincing in light of the events of the film – the fact that Earth is now very much aware of the existence of hostile aliens with vastly superior technology means that humans had better get to work on leveling the playing field if they want to remain safe and free – the threat to New York City at the end of the movie is not directly a result of the Tesseract at all. Loki uses it to open a portal through which the invasion begins, but the government’s solution is to attempt to destroy New York, thereby destroying the portal and the Tesseract at the same time; the government is not willing to risk losing the world to invaders even if it means potentially destroying the object they hoped to use to protect themselves from those very invaders.

So while the Avengers, as both de-facto government agents and simultaneously non-authoritarian forces, live out the complicated attitude toward authority in their movie at times supporting and at other times opposing the will of S.H.I.E.L.D., Batman, the “power source” of the threat to Gotham is contrastingly simple in his attitudes and goals – the very possibility of the fusion reactor being used as a weapon is enough for him to shut down the project. Batman considers himself to be the highest authority, and the idea that anyone else can use his power is abhorrent (and indeed his distrust is proven to be appropriate, since the citizens of Gotham turn on the forces of order as soon as Bane gives them the choice). The Avengers, though, have a more nuanced approach. They neither consider themselves as paternalistic authority figures, nor do they inherently distrust either the organization or the motives of the government they (occasionally) report to – even when they disagree with their methods to the point of actively opposing them.

How the heroes dispose of the bombs and save the cities in question is also similar but different: while Batman manages to fly the fusion reactor far enough off the coastline and over the Atlantic Ocean (Gotham is in New Jersey, apparently) that the explosion fails to kill anyone, Iron Man flies the government-launched bomb through the portal and uses it to destroy the alien invaders’ mother ship. Of course there was no way that Batman, under the circumstances, could have used his bomb as a weapon against that film’s antagonists, Iron Man could easily have simply flown his bomb out over the ocean. But he didn’t; instead, he again subverted the power of the authorities and channeled it in order to accomplish their mutual goal in his own way rather than theirs. That ambivalent relationship to authority is here demonstrated yet again; Iron Man and the Avengers don’t object to the use of weaponized nuclear power per se – they just want to make sure that it’s pointed in the right direction, unlike Batman, who apparently saw no possible positive use for his fusion reactor if it were weaponized even if it were in the hands of the U.S. government, because Batman sees himself as the only legitimate authority in the story, and even Commissioner Gordon, in a sense, works for him rather than the other way around.

Finally, even their death-and-resurrection has this same contrast. Iron Man destroys the alien mother ship and then falls to Earth in the wake of the explosion and the dissolution of the portal. He seems, for a minute, to be dead. But it turns out he’s perfectly okay after all. Batman also survives the nuclear blast (his plane turns out to be remote-controllable), but he uses the explosion as an opportunity to fake his own death and go into retirement. This, again, is all about authority. Just as Iron Man makes no effort to conceal from the public the fact that he is Tony Stark, the revelation that Batman was Bruce Wayne would be tantamount, in the Caped Crusader’s mind, to the death of both facets of his personality. By “killing” Batman, sacrificing the part of himself that has responsibilities due to the power of authority he wielded (because of having taken it for himself), Bruce Wayne is free to go on living. It’s implied that John Blake takes over as Gotham’s protector, that’s not because Bruce has done anything to pass the cowl to a protégé; apparently he decides that he’s done enough for Gotham, and leaves it to its fate. He can do this because authority, to Batman, is about maintaining control more than about protecting people as such – it’s an ideological concern rather than a humanitarian one. For Iron Man and the Avengers, it’s not the authority that’s important; they all need to be convinced to act as the government’s weapons and are all, at first, happier to let Nick Fury and S.H.I.E.L.D. deal with threats on their own, however they please. In The Dark Knight Rises, notions of power are fundamentally associated with deception and hiddenness – when truths are revealed, when people are unmasked, the result is destruction and anarchy. The world of Avengers, on the other hand, is in a sense democratic, viewing power as a dialogue between more-or-less equals (if occasionally a very heated one), wherein openness and honesty are what gives authority figures legitimacy.

Astounding work, as i’ve come to expect from the OTI website, but alas 1 glaring mistake. The group that Nick fury and S.H.I.E.L.D. answer to is not the U.S. government but actually a group World leaders from around the world. The United States Government was approached by Joss Whedon and the Avengers crew, but declined to be indicated in this movie as it was unclear as to where SHIELD and Fury would fit into the current Administration. this was mentioned on some website and i don’t have the link, but i remember thinking it was dumb of the American Government, not to get behind what was at the time thought to be a groundbreaking movie event. After reading this I realized that (in my personal opinion) They were scared that other countries would not like the idea of America essentially overseeing a group of people who would become the next Nuclear Deterrent.

Basically the US is quite Frankly the home base of nearly every superhero/metahuman/Alien/mutant/other group of beings ever. I know other countries have supeheroes, and i know that America, isn’t responsible for everything but it does seem to have the monopoly on the genre. I appreciate the opportunity to voice my beliefs and reconize that I could be completely wrong. I look forward to people responding and possibly changing or refining my focal point. Thank you.

-Dok

While not involved in the nuclear weapon itself, Stark also has invented a clean energy source that gets turned against him, in his case, his clean energy generator is used to run the tesseract and open the portal to begin with.

In both cases the billionair playboys’ technological philanthropy is used against them by the villains.

I really appreciate your articulation of the films’ differing approaches to legitimate power, particularly in the Avengers. The Nolan films view of people and the need to hide the truth (and the terrible effects of revealing it) have been something I’ve been chewing on since The Dark Knight. I believe you lay everything out quite effectively here.

“The bad guys, led by juiced-up anarchist Bane, his legion of chaos, are Gotham’s own citizens.”

How sure are you about this? I’m pretty sure that Bane’s “legion of chaos” was almost entirely his mercenary army/freed prisoners from Blackgate. They were the ones who negotiated with the Army, they patrolled the city, and they were the ones who fought with the police at the end. The most we see of Gotham’s citizens participating in the chaos is during one scene were some people party in a luxurious apartment and maybe during the trials in the peanut gallery.

I mean, it just wouldn’t make any sense. Batman correctly stated that Bane would never really give great power over to the people of Gotham (he gave the detonator to Talia), so why would he use a bunch of middle/lower class citizens to rule Gotham and fight the police? The Occupy rhetoric was just a cover to inspire his mercenary army/Blackgate prisoners; the only reason he conquered Gotham was to break Batman.

“It’s implied that John Blake takes over as Gotham’s protector, that’s not because Bruce has done anything to pass the cowl to a protégé; apparently he decides that he’s done enough for Gotham, and leaves it to its fate.”

Could you elaborate more on this? From what I remember, Bruce DID do a lot to pass the cowl. He remade the Batsignal for Gordon, reestablishing the link between the Police and Batman,and he led John straight to the Bat Cave, where he would find all the necessary equipment/information necessary to continue the Dark Knight’s legacy.

Now this next part is a stretch, but I would also claim that Bruce was subtly preparing John to become the city’s protector, both directly and indirectly. He tells him why a wearing mask is important, why there are times it is necessary to operate outside the law, and most importantly he (Batman and Bruce Wayne)served as an inspiration to John when he was growing up in the orphanage.

I now I’ve been going on for a while now, but my point is that Bruce DID care about what happened to Gotham after he left and what would happen to its people. He took several steps to ensure that it would still have a protector after he retires.

To quote Bruce Wayne from Batman Begins: “Gotham isn’t beyond saving…There are good people here.”

In support of this question I’d suggest thinking about TDKR not in terms of ‘occupy’ but rather as a reaction to ‘The Arab Spring’. At the time when TDKR was in development (I believe) there were questions (which have since been proven true) about dissident elements in some counties that were co-opting they public support for change as a way of gaining control themselves; leaving the original complaints of the public unaddressed.

Like TDKR the people in the streets were just as active as anyone, but the momentum was driven by ‘brotherhoods’ supplying heavy weapons to any thug and outcast they could influence to follow them. In several countries (like Egypt) the original protesters continued through the entire regime change, and are now being oppressed by the new boss (same as the old boss).

As a secondary consideration, the radical form of deregulation that Bane implements is “like the Tea Party on steroids”.

Either interpretation offers a similarity that ‘occupy’ didn’t… a power base pretending to be in alignment with popular frustration.

Even with this difference in perspective great article!

I think the army fighting the police at the end is a mix of Gothamites and people brought over from… wherever… by Bane. It’s implied during the raid scenes of the houses that it’s angry mobs of private citizens dragging out the rich people. Further, there are women in the crowd at the end, and up until that point, any thug shown near Bane had always been male- so unless he suddenly had females in his personally selected ranks, those must be citizens of Gotham. The rhetoric was a load of crap, yes, but keep in mind Bane’s rhetoric serves the same purpose as the test with the ferries in The Dark Knight, but on a grander scale. Talia, through Bane, “introduces a little anarchy” and this time, the citizens of Gotham fail to show that they’re good. This gets brutally reiterated by the prison break- which, yes, is spear-headed by Bane, but the citizens of Gotham are totally fine with it and mix and mingles with the prisoners. Talia’s main goal was to finish her father’s legacy, meaning destroy the city that had become so dark and terrible- allowing Gothamites to wallow in their own mistakes for a few months was to prove to the world that Gotham was beyond saving, as her father had said it was in Batman Begins.

So, in other words, no, I don’t find it hard to believe some of Bane’s men were in the crowd; I find it hard to swallow that the entire army fighting the police in the climax was Bane’s followers.

I do, however, agree with you 100% about Blake. :)

I just re-watched the fight at the end and I didn’t see any women in Bane’s army. I did see some female police officers, so they may have just been mixed in with the crowd and that’s what you saw (I could totally be wrong here though).

As for the looting scenes though, I’m pretty confident that those were Blackgate prisoners. The looting montage comes right after Banes frees them, so a certain amount of time has passed between the football game declaration (perhaps a sly reference to the Tennis Court Oath?) and when the looting starts, perhaps a few days (it takes time to move Tumblers and men across the city, not to mention they probably needed to sweep the city to make sure there was no resistance). If Bane’s speech really had the effect of unleashing the bad in Gotham, why would the citizens wait that long to start looting? The fact that the scene where Bane frees the prisoners immediately precedes the looting montage leads me to believe that it is the recently freed and armed prisoners doing the looting.

I didn’t see any specific instances of mingling between citizens and prisoners. I mean, just because the city has fallen into chaos, doesn’t mean that its safe to hang out with convicted rapists and murderers.

I could keep going, but my main gripe with the articles claim that it was Gothamites vs. GCPD is that there is very little textual evidence supporting it. It just makes more sense to use the vicious criminals and experienced mercenaries to run the city and fight the police. I saw the fight at the end as a fight between the best and worst elements of Gotham(Bane and the criminals vs. Batman and the police), a culmination of Batman’s efforts to help Gotham save itself from itself.

I just think that if Christopher Nolan wanted it to be the citizens of Gotham doing all this, he would have made it a bit more obvious, you know?

Fair enough. I haven’t watched it since December, so if you just did, I’ll take your word for it. I do remember seeing an angry woman in the front of a crowd at some point, but maybe that’s the beginning of the looting scenes- the image struck me the first time I saw it in theaters, and I can’t help but focus on her every time I’ve watched it since that first viewing. So to me, that implies that even if it’s during the angry looting, women would be part of the ranks during the standoff at the end. And also, like with other Nolan movies, I’m taking a lot of implicit luxury, basing this off of the fact that since they never directly show the prisoners in their own encampment or something, they’re re-incorporated into what’s left of Gotham’s society. I honestly may be remembering this incorrectly, too, but does he give his “let’s free the prisoners because the Dent Act was BS” speech to Gothamites? Or is it just his minions? If it’s the former, then that, too, implies they’d be part of the crowd.

I guess my feeling is Nolan wouldn’t make it super obvious, because that’s not his style- sure, some things are hitting you in the face with a hammer of subtlety, but others, not so much. He prolly left it ambiguous on purpose to generate the kinds of thought exercises and discussions we’re having right now, in fact. He very well may have a solid idea in his head, but there are a million things in his movies that are left to interpretation on purpose, and just who’s fighting whom at the end of this could be one of them.

Thank goodness to! I feel like Nolan’s movies are exceptions to the rule that Hollywood appeals to the lowest common denominator. Not everything is explained and you can really chew on it for days afterwords.

Also, I think his “let’s free the prisoners because the Dent Act was BS” speech was televised, so he was probably talking to the citizens of Gotham.

Gab makes a really good point about Nolan’s intention, I definitely think he leaves certain things subtle or ambiguous to prompt analysis and discussion… even though he himself knows exactly what the “real” details are.

Going back to his first 2 movies there are numerous visual contradictions of the narration, specifically shown at times when the narrator isn’t being entirely honest. But you’d never catch them on the first watch.

One of those visual cues that seems particularly meaningful (to me) in TDKR is the presence of weapons and armor, and using it as a key answers a few of the questions you pose.

Bane’s “True Followers” are in full mercenary “uniform” from their first appearance on. The degree to which this uniform is present or lacking in various scenes then explicitly gives the true narration in spite of what Bane says.

So during the Blackgate speech the only ones who actively “free the oppressed prisoners” are fully uniformed Bane-archists. The Gothamites are represented almost solely by the TV cameras (which is Bane’s true audience). The prisoners are immediately armed by Bane.

In the montages that follow we are given representations of 3 levels of involvement.

3 – Unarmed Gothamites – Presumably the genuinely disenfranchised, swept up in the momentum of the storm. Primarily active in the looting montage.

2 – Armed Gothamites – Primarily the thousands freed and armed in the Blackgate scene. The majority presence in the “Revolutionary Tribunal” and “Final confrontation” scenes. Remnants of “The Mob” who have become “the mob”.

1 – Uniformed Banearchists – Since an unspoken line of separation is preserved it’s likely these are all men who are on Bane’s side from the underground days. Consisting of a large group of mercenaries and a core of True Believers who are probably League of Shadows initiates.

In all strategic scenarios (like guarding the police and in patrolling convoys) we see ONLY uniformed men.

So for the looting scene we see a mix of groups 3 and 2, but I think it’s safe to agree with your logic that this does not not happen without the instigation of the freed prisoners (as demonstrated by the timeline).

In fact we don’t actively see any members of group 3 harming anyone, I’m not saying they’re guiltless, but they’re not singled out individually as evil. (That difference between Guilty and Evil has been a constant dialogue in Nolan’s Batman series.)

Watching with this narrative cue in mind we see that the heavier the “People of Gotham” rhetoric gets in a scene the less likely it becomes for an average citizen to be present.

To over-imagine the role of average citizens means completely missing the theme of “Evil rising where we tried to bury it”.

Metaphorically that means organized crime, and literally it means Blackgate. So it’s very significant that Dent Act convicts are very active in these events.

Also consider how John Daggett has taken organized crime to a new level. There’s at least implications that he has begun to fill the void left by the crumbling Falcone empire. Even though we’re not shown the extent of his underworld ties, it’s plenty to say that this is a man who has engineered a coup in Africa and has smuggled in a mercenary army. He may have dropped the mobster persona, but he is the Evil of organized crime rising again.

“Banearchists”= awesome.

The looting definitely involved non-Blackgate folk including Selina’s friend. “It’s everyone’s house now.”

As for the composition of Bane’s army, don’t forget that he had recruited the homeless and orphans.

I’ve been meaning to write something for a while about how the whole trilogy is basically about whether the people of Gotham City are assholes or not. In the first movie, Liam Neeson says, “These people are assholes,” and Bruce Wayne says, “No, they’re actually totally decent human beings.”

In the second movie, the Joker says, “They’re only as good as the world allows them to be. I’ll show you. When the chips are down, these… these civilized people, they’ll eat each other.” But Bruce Wayne seems to be right, and the people on the ferries surprise the Joker by not killing each other. “This city just showed you it’s full of people ready to believe in good!” Batman says triumphantly.

But the third movie seems to prove Joker totally right after all. The people of Gotham ARE actually assholes after all.

We don’t know that Bane recruited homeless people orphans/orphans into his army. The biggest clue we get comes from the boy John talks with near the beginning, who says some people are saying that there’s work underground.

Now which fits better…

1) Bane recruits these inexperienced and socially maladjusted individuals into his army, which keep in mind already contains a large number of trained and dedicated (not to mention well-armed) mercenaries.

OR

2) Bane uses the homeless/orphans as secret (and cheap) manual labor to build his underground hideout and lay out his explosive-laden concrete across the city, an undertaking which would require a lot of manpower.

Also, to Matthew

We never really see everyday Gothamites participating in the chaos, outside of a small portion joining in the looting.

The breakout at Blackgate, moving the bomb around the city, the fight at the end: all these things are done by the Banearchists/Blackgate prisoners.

Gotham isn’t so much full assholes as it is full of damsels in distress, waiting for a hero to save them. Batman is the hero they deserve; a person to inspire the people of Gotham to rise up and take back the city (if this sounds familiar, it’s because Bane corrupts Batman’s rhetoric to serve his own ends). The massive fight at the end represents the climax of this struggle; Gotham’s police are finally fighting for the good of Gotham.

Sorry for the double post!

Christian – I don’t think it’s nearly as cut and dried as “It’s the criminals that are doing all the bad things, and the average citizen is cowering in fear waiting for a savior.” Selina Kyle warns Bruce Wayne: “There’s a storm coming, Mr. Wayne. You and your friends better batten down the hatches, because when it hits, you’re all gonna wonder how you ever thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us.” And sure enough, once the police are gone we see rich people getting kicked out of their Brownstones. It’s the freaking French Revolution, but with a frozen river instead of a guillotine.

I agree that Nolan makes it (purposely?) murky by freeing all the criminals. We’re never sure how much of the anarchy is the Scarecrows of Gotham getting free reign, and how much is “giving Gotham back to the people,” as Bane would say. Certainly, he WANTS Gotham City to look bad, so it makes sense that he might SAY he’s putting the common man in charge while simultaneously leaving everyone at the mercy of mass murderers.

You know what I would have wanted to see? Regular non-police citizens of Gotham rising up against Bane’s guys in the final battle. It’s JUST the police standing on their own.

So I’d say that the question of Gotham’s true nature isn’t really made clear. Are they animals who will tear each other apart the second they can? Or are they good people who are put at the mercy of thugs they can’t possibly oppose? Or to put it another way, is Occupy Gotham a real grassroots movement (like Selina thinks) or is it just an “astroturf” campaign?

Apparently when we’re this many levels deep we lose the “reply” button :-)

I’d love to see a “Referendum on the Assholyness of Gotham” Article.

And without wanting to contaminate it’s future potential I have some comments and an “ultimate question” to ponder.

I want to say lots of things about Noir, and the hope for individual redemption remaining despite the impossibility of societal redemption… but I’ve gotten into my first batch of homebrew beer and fear that it’s going to make me think I’m smarter than I really am… so I’ll keep it simple.

In TDKR we actually see the fulfillment of Batman’s original mandate “Gotham isn’t beyond saving. Give me more time. There are good people here.” In that individuals are rising up to meet extraordinary demands even if the city as a whole has been complicate or ineffective.

I think the focus has been turned to whether Gotham’s institutions are redeemable or not. The verdict of which I guess depends on whether we see the final battle as the Institution of The Police rising or as a collective expression of individual aspiration.

With those couple of points hanging in the air the question remains to be addressed; Is Jim Gordon the true hero of the series?

Or or or, is it Batman the idea, not Batman the man?

What a well thought out, well written, intelligent piece. I really enjoyed this article. Thanks Richard.

“DKR has been largely seen as a not-particularly-veiled critique of the Occupy movement and its perceived indiscriminate rejection of authority and laying the blame for their ill-defined problems on the so-called “one percent.” In DKR, Batman has restored order to Gotham City by sacrificing his reputation to the memory of the deceased Harvey Dent and cleansing the police force of corruption by the resulting ascent of archetypal Good Cop Jim Gordon. That is, in DKR the police are decidedly the good guys, Batman’s army representing the forces of order. The bad guys, led by juiced-up anarchist Bane, his legion of chaos, are Gotham’s own citizens. The ninety-nine percent become Bane’s willing executioners, joyfully turning the city into Ayn Rand’s worst nightmare and unwittingly allowing Bane to gain everything he needs in order to destroy them.”

There’s a lot of wrong to unpack here (in this otherwise fine article).

-DKR may have been seen as a critique of the Occupy movement, but the film was written (and in mid-production) when Occupy happened (the filmmakers briefly considered filming some scenes in it, but wisely decided that billion-dollar corporate entertainment franchises co-opting anti-corporate social movements was probably a bad idea).

-The police are not just “good guys” and agents of order; they’re seen as ineffectual at best most of the time (the first climax of TDK is Batman fighting off a series of SWAT teams because that’s the easiest way to stop them from accidentally killing a bunch of hostages), and the end of TDK puts them directly at odds with Batman. Arguably their moral standing is even further muddled in DKR, given Gordon’s guilt over his lie and the draconian legal punishments of the Dent Act.

-As noted above, most of Bane’s army are his followers; from what we can tell in the film, most of the 99% are huddling indoors or looting indiscriminately, not taking up arms under Bane’s banner.

-Nor is the film defending the 1%, whose short-sighted greed help enable Bane’s plans.

Overall you have a pretty good and interesting handle on The Avengers, but less understanding of DKR.

I think the latter is mainly interested in interrogating the sources of power/authority. Where Batman Begins concerned itself with the ways in which an individual can retain power in the face of a corrupt collective (Gordon against the cops, Bruce against the mob/the League of Shadows), and TDK used the Joker to examine how people behave in the absence of authority, DKR’s Bane exposes traditional sources of power/authority as false (nullifying the cops, using physical strength against the rich, countering Batman’s toys with skills earned from life experience, turning the nuclear bomb against its creators, etc) so that we can see where the foundation of true power lies.

The “now it’s everyone’s house” scene suggests that the movie is at least in part a critique of, if not Occupy itself, at least the sort of anarcho-socialist ideology that the movement espouses.

I suspect that whatever the true message of DKR was, it got rather muddled in the editing room as it was being pared down to a reasonable length. But basically, Nolan’s gone on record as wanting to parallel the French Revolution, where the short sighted greed of the aristocracy triggers the short cited rage of the proletariat, and everything just gets steadily more awful. As such, it’s basically a critique of neither the 99% or the 1%, but rather the entire 100% of us who aren’t Batman.

The French Revolution connection makes a lot more sense, given that Gordon reads the final lines from “A Tale of Two Cities” during Bruce Wayne’s funeral.

I feel like I missed something, since a few commenters said the army fighting in the end isn’t made up of Gotham citizens. I just don’t buy that, though.

Anyway, I liked the article, and any critiques I had have already been brought up.

Another, more broadly-placed parallel is that the good guy(s)/gal figure out what the Big Bad is going to do, but are unable to stop it. Black Widow figures out that Loki wants to make Banner angry, but she and the rest of the Avengers are unable to prevent it from happening; Batman knows Bane is going to make a nuke, and he can’t do anything about it. The difference lies in how the Good side figures out the Bad side’s plans- Black Widow does this through interrogation of Loki (and while she plays it off as an act at the end, see Fenzel’s piece about sexual violence to find out why she’s just acting like it was all an act), Bane gives his info up freely as he’s whaling on Batman. Of course, both Bad Guys are totally doing the stereotypical Super Hero Villain Monologue, but what causes them is different.

The original Iron Man comic was basically an illustrated version of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.

http://colossus.mu.nu/archives/311264.php

Batman was originally a rip off of The Shadow who was a rip off of Zorro.

Both Bruce Wayne and Tony Stark inherited their wealth from rich daddies. Both maintain a public worthless playboy persona. Both come up with excellent weapons which the government would love to get their hands on. Essentially they’re both Hank Rearden except one runs around beating up poor people from the shadows while the other blurts out “I’m Ironman” at a press conference. Gotham is a city of slums and mansions. Tony Stark usually lives in LA….which is mostly one large suburb, if he isn’t hanging out in Avenger’s Mansion.

p.s. Bruce Wayne may actually be dead. It’s implied that Alfred hallucinated his vision of Bruce and Selena riding off into the sunset (or rather the diner) together.

Oh, and it’s been pointed out that Batman in 2003 “Batman Begins” is former President Bush and Batman in 2008 ‘The Dark Knight’ is actually Dick Cheney. Which probably explains the anti-Occupy, anti-plebian tone of “The Dark Knight Rises”.

http://washingtonindependent.com/509/batmans-dark-knight-reflects-cheney-policy

http://oxfordstudent.com/2012/08/09/batman-the-bush-years-the-acceptable-face-of-torture/

1) The “anti-Occupy, anti-plebian” rhetoric is all Bane, and is meant to represent a perversion of Batman’s mission to inspire the people of Gotham to do good. As was already said in the comments above, TDKR was in production before the Occupy Movement even started, so whatever connection there is is more from applicability than direct metaphor. Also, as it has been gone over ad nausem in the comments above, it is pretty clear in the movie that the most of the really bad stuff done during Gotham’s occupation was done by Bane’s mercenaries/Blackgate prisoners, so the 99% aren’t the ones at fault here.

2) Alfred couldn’t have hallucinated seeing Bruce, because Selina was there with him. If he was going to hallucinate that Bruce was alive, why would he hallucinate that Selina was there with him as his wife? Wouldn’t making it Rachel make more sense? Also, if Alfred did hallucinate seeing Bruce at the cafe, then why did the movie show us that Bruce fixed the autopilot and that his mother’s pearl necklace was missing (being worn by Selina)?

3) I always thought Tony Stark and Iron Man to be a parody of Atlas Shrugged (Maybe not the comic, but definitely the movies). Tony isn’t playing at being a playboy- he really is a womanizing, alcoholic, egotistical jerk. I always thought the Iron Man movies were playing off that old superhero trope “with great power comes great responsibility”, just from a different angle.

Consider who the villains are and how the government is portrayed. The villains are all genius inventors/industrialists (Obadiah, Ivan, Hammer) who use their “property” for their own benefit to the detriment and destruction of everything around them. Heck, Tony was a big part of the problem, and even when he became a hero he is still wildly irresponsible and frequently puts people in danger.

The government on the other hand is portrayed much more favorably. Tony’s best friend is a Colonel in the Air Force and serves as Tony’s voice of reason, the only one who steps up and tries to rein him in. Also, it was only with the help of the government developed War Machine that Tony was even able to be beat Ivan. Sure that one Senator was a jerk, but in the end he was right about the threat of escalation.

I know that #3 may not have been the point of your post, I was more responding to the post in the link than anything else :)