So let’s get one thing out of the way first: I didn’t love the ending of Mass Effect 3.

(Warning: comprehensive SPOILERS for the Mass Effect series to follow)

To fight house-to-house in the liberation of London, like besieged Allied troops in the best WW2 flick, was plenty. To hold off unending waves of Reaper aliens while waiting for a missile emplacement to lock on target was more than enough. To limp desperately through the remains of the Citadel was gripping, poignant, and a fitting end.

The conversation with the “child A.I.” was a bit twee, especially since this was the same “child” that had been showing up in Shepard’s nightmares up to that point. Bioware’s dialogue writing has been better than most video games, but is still raw enough to highlight the limits of the genre, and their tendency to reveal plot through dense blocks of expository dialogue is the company’s biggest weakness. As such, a conversation wherein one character reveals the Secret Nature of the Galaxy to the protagonist is par for Bioware’s output, but hardly laudable.

That, I had a problem with. But the rest of the ending, not so much.

(Yes, there is the plot hole of how the two crew members who came with you to the siege of London failed to make it aboard the Citadel, yet somehow made it back to the Normandy in time to escape the destruction of the Local Relay. So that’s a bit sloppy. But I don’t think that’s the source of the Internet’s outrage)

For those of you who weren’t otherwise familiar, there was a massive controversy surrounding the ending of Mass Effect 3. Thousands of fans petitioned Bioware to include more uplifting endings, or at least the possibility of such, in a new cut of the game. Fans in the U.S. even took the fight to the Federal Trade Commission and the Better Business Bureau, alleging that Bioware had engaged in false advertising.

I think those tactics are a bit extreme, but it is true that the two distinct outcomes of the original version of the game aren’t that, well, distinct. In both endings, Shepard’s actions result in the destruction of all Mass Relays throughout the galaxy. With this, interstellar communication and transport come to an end. The peace and prosperity that was known throughout Council Space is wiped out. The fleets that followed Shepard to Earth are presumably stranded – although, in the case of the turians, quarians, and geth, it’s not as if they had a real home to return to anyway.

Instructions from NPCs in-game make a big deal of building up your “effective military strength,” or EMS rating. This comes from both recruiting other races of the galaxy to your cause, which requires both tactical mastery and diplomatic aplomb. But it also comes from fighting back against Reaper forces in various hotspots in the Mass Effect 3 multiplayer. Either of these tasks can soak up hours of time. In the end, however, the only difference a high EMS rating makes is whether Shepard definitely dies or maybe survives. Either way, the galaxy is getting shut down.

In the interests of being charitable, I imagine I’d be pretty angry if I invested dozens of hours in online play, as well as sweating over the best offline scenario to bring every race to the table, only to find that I had the same depressing outcome as if I’d played straight through. So I see where some of the rage comes from. That’s not the situation I found myself in, though. I played straight through and got the damned but dauntless ending: cursing the galaxy to a new dark age in order to free it of Reaper tyranny.

And I was fine with it.

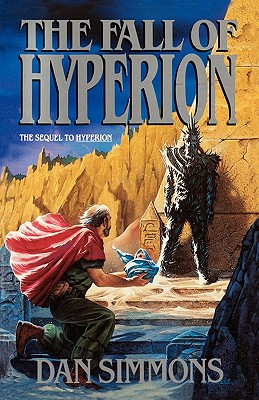

Maybe this was a function of having read the source material that (very likely, but not certainly) inspired the ending of Mass Effect 3: Dan Simmons’ Hyperion Cantos. In this critically acclaimed sci-fi series, Simmons tells the story of seven pilgrims traveling to the distant world of Hyperion. The pilgrims are all citizens of the Hegemony of Worlds, a galactic web of planets linked by teleportation gates called farcasters. These farcasters are a gift of the TechnoCore, a collective of AIs that “seceded” from the human race centuries earlier, following the destruction of Earth.

(SPOILERS for The Fall of Hyperion, obviously)

What the pilgrims discover, in the course of their pilgrimage, is that the TechnoCore has manufactured an invasion of the Hegemony through a false race of cybernetic organisms (“cybrids”). These cybrids are invading and overtaking the Hegemony through the farcaster network. The chief executive of the Hegemony, upon being confronted with irrefutable proof of this conspiracy, does the unthinkable: she orders the destruction of the farcaster network.

The effect is nearly instantaneous, propagating through the galaxy faster than the speed of light:

Thousands of people were caught in farcaster transit. Many died instantly, dismembered or torn in half […] Some simply disappeared. […] After seven centuries of existence […], the datasphere […] simply ceased to be. Hundreds of thousands of citizens went insane at that moment–shocked into catatonia by the disappearance of senses which had become more important to them than sight or hearing. […] Millions of people died when their chosen habitats, accessible only by farcaster, became isolated deathtraps.

Dan Simmons, The Fall of Hyperion

And that’s only the immediate casualties. The economic loss, caused by the implosion of a system in which instantaneous transport across worlds was not only feasible but taken for granted, is incalculable.

And yet the human race survives. Faster-than-light travel is still possible, through a very small number of starships, so people can reunite with their distant families, albeit after decades. Since all the worlds of humanity were somewhat close to Earth in climate, self-sustenance is possible (though there will likely be continued losses as infrastructure adjusts). It’s a radically fractured vision of humanity, but it’s humanity nonetheless.

The most powerful woman in the galaxy decides that millions must die, in order that trillions may survive. She does this by detonating the network of transporters that united the galaxy – a source of tremendous economic uplift, but also a trap laid by a malevolent race of AIs that would be used to destroy all life.

Yeah, it sounds pretty obvious when spelled out that way.

The reason I point out the comparison between Mass Effect 3 and The Fall of Hyperion isn’t just to show off how much I’ve read (really!), but to cast the whole context surrounding Shepard’s decision in a new light. Coming at the end of a video game, it can feel like a letdown. We’re used to video game narratives in which triumphing over a series of increasingly difficult enemies leads to either the renewal of the status quo or the creation of a new, optimistic world. In Mass Effect 3, fighting to the end yields you … two shitty choices. We play video games for many reasons, but one of them is usually to see our efforts rewarded.

And on top of that, calling them “choices” may be a misnomer. Shepard can choose the tone of the new galaxy – one full of docile Reapers or one free of Reapers – but not the ultimate direction. Either way, sentient life is once again scattered across the stars, barred from the communion of souls it briefly knew. If it’s a victory, it’s a really hollow one for those closest to it.

Yet what is the alternative?

Two important caveats: we’ve never held that being a critic requires you to come up with works of art in the field you’re criticizing. To say that a critic’s input is invalid because he hasn’t created anything of his own belies an ignorance of the role of critics, to say nothing of the role of an audience. So you – the Mass Effect fan, consumer, player – are fully within your rights to criticize the ending of Mass Effect 3 as a disappointment, even if you can’t come up with a better ending yourself. Have at it. You will never find me standing in your way.

Second: I know that, given the media involved, the answer to my hypothetical could be “literally anything.” We’re talking about a video game, in which player agency is presumed to be sacred. We’re talking about a work of fiction, in which nothing is possible or impossible until the author gives it voice. And finally, we’re talking about a work of science fiction, in which the conventional limits of the possible can be stretched with some exposition and special effects. It might offend our sensibilities for the game to tell us, “Shepard, you have to push the Destroy All Reapers button before it’s too late!” But we might have an easier time with the game telling us that the Citadel had catalyzed a quantum flux reaction that would neutralize all activity on the Reaper’s hyperspatial wavelength.

Here’s an option: Blasto shows up, shoots everything, saves the day.

So, all that aside, keep up with me.

Gamers, by and large, did not seem to be satisfied with an ending in which Shepard must choose, either joyfully or reluctantly, to destroy the mass relay network. But I presume a more heroic alternative – Shepard stabbing Harbinger in the head with an omni-tool spike and sneering “Reap this,” then being elected Queen of the Galaxy – would have been equally unsatisfying. It would have jarred with our prior expectations of the series.

Recalling the first two games: this is a universe in which hypersentient AIs are lingering in dark space, having seeded the galaxy with tempting technology to lure organic life onto other worlds. Once life becomes sufficiently advanced, these monsters return, pausing first to warp the minds of a select few creatures into serving their needs. When the AIs return en masse, they harvest all intelligent organic life, create a new generation of AIs in the form of the races they just slew, and withdraw for another fifty thousand years.

That’s pretty twisted. What’s more, it’s pretty twisted in a highly systemic way.

The mass relay network that Shepard destroys is the beacon that lures the Reapers out of dark space. It may have brought wealth and peace to the galaxy, but it was also, literally, a trap. Not only was destroying the network a smart play, destroying it centuries earlier would have been even smarter. Humanity and the other Council Races would have been trapped in their own local systems, but they could have continued developing without the interference of malevolent space monsters.

This isn’t just a hard choice. For most people, it might be impossible to act on without going insane. Imagine you had a vision of the future – as certain of a vision as you would need to convince you of its total accuracy – that the human race would die out in a thousand years from overpopulation unless the number of humans on Earth dropped by one billion in the next century. Then suppose that someone put in your hands a button that would kill a billion people. Nuclear explosions, setting off a chain of volcanos, your pick.

Forget for now whether or not you could or would do it: who would you go to for guidance? Who is the experienced leader, the wonder counselor, who would know how to handle such a dilemma? We as a race have ethical guidelines for a variety of interpersonal situations, and we’ve taken some stabs at practices for larger conflicts, even on the scale of war. But what code could guide you in a decision that would render all codes of behavior invalid? Conventional morality withers in the face of a person who’s seen the future and can make a billion people die.

When the system itself – the network of mass relays – is the source of your ills, the only solution is to smash the system. But this revolutionary mindset is never comfortable. The comfortable, pragmatic solution favors the status quo, since the status quo is where all the roads and books and power sources come from. But in the case of Mass Effect, this status quo is also literally killing all advanced organic life in the galaxy every fifty thousand years. It can’t be overcome by safe, conventional choices. The solution is to smash the system. Break it all down. Start afresh.

All that said, is there still an optimistic ending possible to a crisis that’s guaranteed to destroy the galaxy? And could this ending still have preserved the elements of player choice that make Bioware so loved? Let’s hash it out in the comments!

(I know this is a little off from the core of the article but, eh whatever)

My problem with mass effect 3 was never the written endings, or the casual-ization of the series (I do believe gameplay has suffered from more action, less Are-pee-gee)

Its how they got to the ending, after saying how you could not choose “A, B or C” they then made the player choose between: Red, Green or Blue endings.

Those are my sole gripes with Mass Effect.

My preferred ending would have been

>Destroy the Reapers/Relays

>Harvest the technology to remake the Relays (Only Safer)

>Everyone lives happily

>We pretend the Reaper and Collector DLC never happened

Just so I’m clear, the thrust of your argument is that the ending to Mass Effect 3 is not as bad as most gamers think it is because defeating the Reapers via destroying the Mass Relays is the only viable decision given the extraordinary situation.

Correct?

Essentially. I wouldn’t say it’s “not as bad as most gamers think” (if they think it’s bad, then they think it’s bad – own your feelings!), but that it’s hard to come up with an alternative that would satisfyingly end the series without straining suspension of disbelief.

So in order to avoid creating an alternative ending that would strain the player’s sense of disbelief, they created an ending that strained the player’s sense of disbelief?

That, coincidentally, is very similar to the plan the Catalyst had to preserve organic life from synthetic life by periodically wiping out most organic life with synthetics.

Yes, but it doesn’t strain my sense of disbelief, and I’m important.

In all srsness, this is what I’m laboring to prove with the article: that there’s a narrow range of “optimistic endings” to the Reaper-cycle scenario, and that I’m hard-pressed to think of any of them.

Here’s the thing, I didn’t like the execution of the Mass Effect ending, but in concept I agree with you. I have no problem with the destruction of the mass relays and the galactic collapse that would ensue, and rebuilding from the ashes.

I think it’s a false premise for you to say the reason people were upset was that the ending “wasn’t happy” or “wasn’t optimistic.” You mention the hyperbole of Shepard being crowned biggest space badass of all time, Penny Arcade had a similar joke… but the vast majority of people I’ve heard from had a problem with the ending itself, not the fact that Shepard died. The lack of dialogue, wide space shots, crew landing on desert planet (a lot of Bioware games do this, but it’s especially dumb here). A game that was about specificity and attention to detail is suddenly about open-endedness and an artsy French ending. A series that had a whole ton of themes was suddenly ALWAYS about the clash between organics and synthetics. The classic Bioware control over outcomes and endings manifested in a bizarre way with the “readiness.”

It’s not even that I wanted “good ending” vs. “bad ending.” It would’ve been fine with me that the Reaper threat was so large, your team and the civilizations of the galaxy go out in a blaze of glory, but what mattered was that Shepard united all sentient races under a single banner.

They made an ending, just one for a different series of games than the one they made. If you want to leave the details of how the galaxy rebuilds (or not) after the destruction of the mass relays to the player’s imagination, that’s fine. But to just show them blowing up, and leave people wondering if entire star systems are murdered is really unacceptable. Worse is the new “Refusal” ending, where Shepard refuses to destroy the relays. There could be a million reasons why Shepard or Hyperion’s chief executive could choose not to, but Bioware didn’t give it any narrative weight. The game just ends with “I told you so.”

Mr. Perich, I have to disagree with you on your basic argument. I think the controversy was more about the execution of the ending than anything else.

There’s ME fans who certainly wanted a happy ending, but by and large the forums I visited during the whole debacle didn’t have people complaining about that. A downbeat or bittersweet ending was expected; indeed, the deaths of major supporting characters were among people’s favorite moments in the game. General complaints centered more on the likes of “my choices didn’t matter” and/or “I’ll never know what happened to all my teammates.”

What I’m basically trying to say it, the controversy was that ME3’s ending was a “2001: A Space Odyssey” solution to a “Lord of the Rings” problem.

Plus, there were little things throughout the ending that simply primed gamers for a negative backlash. You get railroaded into using a Renegade Option on the Illusive Man in your final confrontation, which is irritating for ardent Paragon Sheps because they have to break character. With the then-recent memory of Dues Ex: Human Revolution, choosing your ending by pulling one of three colored levers was a much-mocked concept, and seeing ME3 use the same device didn’t help. Worst of all, after the ending sequence, you got a prompt telling you to buy more DLC! Which was just salt in the wound for the pre-launch controversy over there being on-disk Day One DLC.

While I agree with what you’re saying, you don’t have to shoot TIM. If you have a high enough paragon you can convince him he is indoctrinated and he’ll kill himself. It’s difficult but it can be done.

P.S.

I’m sorry about posting so many comments so far, I’ll try not to monopolize the comments section and let others get a word in.

I think the controversy was more about the execution of the ending than anything else.

That’s fine, and insofar as people were upset about that, I see their point (if not with the same fervor). But I’ve talked to a lot of people who seemed just as upset about the uniform destructiveness of the endings. That part, at least, I feel I can address.

But … but … one doesn’t destroy the mass relays. One destroys the reapers, takes control of them, or merges with them. Either of these three (increasingly radical) actions neutralizes the reaper threat. At this point, why destroy the mass relays?

The Crucible states that all three actions require the Mass Relays to transfer the effect of whatever decision you make across the galaxy, and in the process they are destroyed.

The destruction of the Mass Relays is the method of deployment, it is the means to whatever decision (i.e. color) you chose.

My gripe with the ending was that the whole purpose of the Reaper cycle was to prevent synthetic life from evolving and eventually wiping out organic life. Ok, so it does involve mass genocide of entire sentient species every 50,000 years or so, but life is still preserved. The system does work. The game even includes a brief reference to malevolent AIs during Prothean times to support this.

In the present game time, however, it’s clear that synthetic life, the geth, is perfectly capable of peacefully coexisting with organic life. The geth are literally given the opportunity to wipe out their creators not once, but twice! Moreover, if a malevolent AI race should threaten to wipe out all organic life (permanently), why couldn’t a fleet of overpowered Reapers just destroy it?

It’s actually much dumber than that. In the Leviathan DLC it is revealed that the Catalyst is actually an AI construct created by the Leviathans (the organic species that the first Reaper was modeled after) that was designed to solve the problem of species creating AIs that rebelled against them.

So these Leviathans, God-like in power, created an AI to solve the problem of AIs rebelling against their creators. Shock of shocks, the AI turned against the Leviathans and created the Reapers from their corpses.

*headdesk*

In fairness, conflict with the geth might be inevitable a few thousand years down the line. Reapers have a lot more data.

“we’ve never held that being a critic requires you to come up with works of art in the field you’re criticizing.”

I know a few people who say that unless you’ve done something in that field, you can’t criticise anyone or anything in that field… which comes across as “I don’t like your bad opinion, so I shall dismiss it as ignorant”.

Yeah, I hear that a lot, and it cheeses me off.

A critic’s role, if they’re doing it right, is to act as a well-informed audience member: the type of person who consumes a lot of a particular genre and subjects it to a level of scrutiny it probably doesn’t deserve (deserve). A hyper-audience member, if you will. So to say that a work isn’t for critics is to say that it isn’t for the audience.

And to say that a critic’s opinion is invalid because “they’ve never created anything themselves” is (1) revealingly defensive and (2) implying that one’s work is only suitable for people who have created things themselves; i.e., other artists in your field. At that point, if your work is targeted to such a narrow audience, it’s navel-gazing. It’s not great.

I’ve never directed a Transformers movie, but I’m pretty sure Transformers 2 sucked.

My issue was how the ending was conveyed in that Shepard’s (and by extension your) agency was taken away without even the illusion of defying the AI’s options.

Honestly it acts as a very interesting parable for bioware games as a whole where you’re given the illusion of agency through a myriad of moral actions but are always guided to the same end. Your choices never really effect the structure of the game.

Take this in contrast with the Witcher 2 where your faction choice in the first act leads to a radically different second act and where the finale locale changes significantly depending on who you save in the third.

I would have been happy destroying the Mass Relays if I (Shepard) destroyed them rather than pressing a button and being told that my actions had wide-ranging effects.

All that being said the ending wasn’t a deal breaker for me, 99% of that game was the most cathartic experience I’ve ever had.

RIP

Mordin Solus

Thane Krios

David Anderson (presumably)

Malachi Shepard

Wow your blog is really living up to its name. You certainly are “overthinking it”

The fact is there is nothing deep about ME3’s ending. It was simply a desperate jerry rigged mess that was thrown together after the original ending was leaked online. (It involved Dark Energy destroying the galaxy) ME3’s developer’s then made things worse by trying to mask their failure with arrogance, claiming people just didn’t get it. They claimed they wouldn’t fix the ending because it would compromise their “artistic integrity” when they had no integrity. If they had integrity they wouldn’t have ripped of Deus Ex’s: Human Revolution’s ending and passed it off as their own.

In conclusion, Mr. Perich, don’t bother white-knighting Bioware. They deserve the hate.

Wow your blog is really living up to its name.

Hey, we got another one.

Damn, how did I not catch that parallel? But to follow that train of logic maybe the reason fans didn’t like the ending to ME3 is that it was too second actish? The Fall of Hyperion isn’t the end of that particular story, Endymion and The Rise of Endymion provide a redemptive conclusion to the overall narrative.

Also, and I realize this is completely childish, but I wanted to kick Harbinger’s teeth in. Tentacles. I wanted to kick Harbinger’s tentacles in.

I’d loved to see the merging ending compared to the last DUNE book which had a similar ending.

I kind of get what you’re saying about the destruction of the mass relays being a thematic necessity given their role in the Reaper cycle. But I didn’t really need a “good” ending to that storyline. A “Harvest this!” ending would have been silly but I would have shrugged it off because the Reaper storyline was never the point of Mass Effect for me. They’re just a somewhat silly inciting element. The game needed an existential threat to drive the big geopolitical drama.

And said geopolitical drama is what actually brings me to the table. The interesting stories for me had to do with the quarians and geth, with krogans and the rachni and the genophage, and with humanity’s awkward integration into galactic society. Not only are these stories more interesting than “blargh evil spaceships from the dawn of time!”, they’re also elements where the player has something resembling real agency. But the apocalyptic nature of the ending swamps these elements entirely. Making peace with the geth or curing the genophage becomes largely irrelevant in the face of the total destruction of interstellar society.

Not only are these stories more interesting than “blargh evil spaceships from the dawn of time!”

This is a fair point. I had the most fun with ME:2, largely because (1) the series really hit its stride with gunfight controls and (2) the stakes were high but not terminal. I almost felt bad doing sidequests in ME:3 because the Earth was on fire. Everything was so grim and depressing. ME:2, at least, you felt you could breathe a little.

I had similar issues with Dragon Age, another Bioware joint.

That’s just one of the compromises that ME:3 has to make to be a game. When General whatshisname tells you “Quick, defend the landing zone!” it actually means “Quick, get to the weapon bench, because there’s no way I’m bringing Garrus into combat with that crappy off-the-shelf assault rifle, and I better check one more time to make sure I didn’t miss any weapon mods before I head out, I might not be able to come back here later.”

Despite all those compromises (to me the trips to the Citadel were the most jarring, I’m really going to a dance club right now!?) the game maintained that sense of urgency surprisingly well.

I agree one thousand percent. Here we have a great Western RPG series with memorable character moments and cool worldbuilding and complex interstellar political conflicts that hamstrings itself with doomsday robots. We have all the great missions and dialogue in Mass Effect 3, and it ends by talking to ghosts and pushing a button (also see: Assassin’s Creed 3, spoilers). Mass Effect 2 was an amazing experience that fleshed out a lot of backstory and lore, yet you have to finish the game by fighting a goofy gigantic Terminator.

Shoehorning in “SAVE THE WORLD” tropes: not just for JRPGs anymore.

(Sorry for my poor english)

This is what in wanted as an ending:

Renegade Shep : Threat the starbrat to blow up the whole galaxy with rigged gates if they dont surrender/leave. Baddass bluff check. (Or not ^^)

Parangon Shep : Epic diplomatic discussion (Planescape style) with the star brat proving that his vision is flawed (With the geth and quarian peace and the half-synthetic shepard as proof) Reaper agree to leave for a millenia and will come back to see if the peace remain.

Plain and simple :)

Is the illusion of choice not one of the central themes of ME? Think about it, all 3 games involve a mass of choices that are supposed to have far reaching consequences, but by the conclusion of each game you must follow the same per-figuration. Sure you can colour the ending slightly, but the big ‘choices’ at the end of each game bare no relation to what came before. No matter how you play ME1 for instance you have to choose between saving the council or preserving the human fleet.

Further to this one of the main themes is H.P.Lovecraft’s Cosmicism, where the human race is impotent in the face of an omnipotent terror lurking outside it’s sphere of influence. The Reapers represent the galaxies impotence, it’s naivety and hubris. The ending of ME3 choose to reinforce the galaxies insignificance in the face of such a power, we are forced to choose the AI’s options. There is no breaking free, no free-willed ending where Shepherd goes rogue. How could that be possible, because we didn’t punch Khalisah Al-Jalani? To do so would assert that the galaxy was not impotent, naive or hubristic.

I agree that it would have been nice to see what happened to some of your team, and there are clearly some lazy plot holes that leave a hollow feeling. But Bioware should be applauded for making a video game, the genre of interactivity and of choice, where the player’s free-will itself is questioned.

I agree, but I think Mass Effect’s Reapers are a failed attempt at using themes from Lovecraft’s cosmic horror. The Reapers and Leviathan do bear some resemblance, but the Elder Gods are way more effective. First, humanity has literally no hope against Cthulu, et al. were they ever to return, yet in Mass Effect Shepard through space commando awesomeness saves the day. If Mass Effect really were about the illusion of choice in the face of such a threat, the galaxy should have lost in all the scenarios (I would’ve been fine with that). Second, the Elder Gods are scary because they are unfathomable, and their motives incomprehensible by human minds. The Reapers get way less mysterious when you have long conversations with Sovereign, or when Harbinger keeps saying “Assuming control” and then trash talking Shepard during battle. Worst is when you explain their stupid origin story and their motives. So the Leviathans wanted to solve the problem of all these “lesser” organic races that would kill themselves off by making robots that would rebel against them, and their solution was to make a race of robots that rebelled against them. Brilliant.

Is there any Lovecraft fan out there who thinks Cthulu would still be scary if the protagonist were to talk to him, and hear from his weirdass alien mouth IN ENGLISH “I will destroy you! Now let me tell you the story of my creation, and why I want to take over the world and maybe read you some poetry I wrote.” No. The Elder Gods are scary because humans will go crazy and be destroyed and we are entirely beneath their notice. The world would end as simply and meaninglessly as you stepping on an anthill on your way to check the mail. That just isn’t what we get with Mass Effect– the Catalyst converses with us and eventually lets us choose, which is the opposite of the impotence that cosmic horror embodies.

I absolutely agree that Bioware shit the bed when they explained the Reapers’ history. Personally I would have been quite upset if, regardless of your actions, the outcome is the extinction of sentient organic life throughout the galaxy. I can accept that sort of tragic (yet potentially meaningful, enlightening, or otherwise worthwhile) ending in a novel or a movie. Those sorts of entertainment take between three and twenty hours of time and up to about fifteen dollars (counting drink and soda) to complete. The Mass Effect series takes about seventy to ninety hours and roughly $150, not counting DLC.

Movies and novels aren’t passive precisely, the best of them certainly engage the viewer/reader critically and intellectually, but video games require active engagement on an entirely different scale. The player is Shepherd in every meaningful way, and to tell that player, after that huge investment, that it was all for nothing would be unforgivable. It isn’t like every Lovecraft story ends with the Old Ones destroying humanity (btw, for all that we’re told their motives are inscrutable, they certainly seem to boil down to “kill people” most of the time) if Shepherd had managed to repulse the Reapers, either temporarily or permanently, without having that stupid kid explain them to the player at length it would have been much more palatable.

I’ve thought about it and think I fundamentally disagree with the opening premise of your post. Sure Bioware’s got their thumb on the scales the whole way through to insure you pass through te specific missions and story beats tey think are important, but to the degree that’s even noticeable from the player experience, I’d hesitate to call it a central theme. Quite the oppositte.

One of the aspects of the series that really should be a drawback but basically ends up making the series is the way that serendipity and Shepherd’s Mary Sue hypercompetence grants the player a ridiculous amount of agency over galactic events.

This is a series where leaders of nations base their decisions on the opinion of a midranked naval officer from a foreign military. Where major characters live or die depending on whether or not their boss decided to take an active interest in their personal psychological baggage. Where you can interrupt an argument between two strangers and, instead of being irritated at your sticking your nose in their business, they’ll instead immediately follow you advise and then later as a result you’ll see in your war assets that this has somehow lead directly to a sea change in people’s behavior. This is a series where the potential genocide of three-five (depending on how loosely you want to use the word) different sentient species hinges on one person’s off the cuff opinions on the subject.

It’s undeniably ridiculous, but it’s bred into the DNA of the series, and the ending will always feel more like the point where the rules unexpectedly change than a continuation of an ongoing theme.

To be fair:

1) Early in the first game you are inducted into the Spectres, the Council’s secret agent/special forces unit that enforces the will of the Council and ensures the safety of the galaxy through extra-legal means. In the following games, everyone knows that you’re the guy who defeated Saren and the Geth. Not to mention that you form several close ties to powerful people in your adventures (Wrex/Wreave is the leader of a clan of Krogans, Tali’s father was an Admiral in the Quarian Flotilla, Liara becomes the Shadow Broker, etc.) Suffice to say that you’re not just “a midranked naval officer from a foreign military”.

2) I don’t think it’s entirely fair to say that “the potential genocide of three-five…different sentient species hinges on one person’s off the cuff opinions on the subject.” Assuming that you’re talking about the Genophage and the Geth/Quarian conflict, the variables leading up to their resolution take into account several critical decisions that span all three games. Whether or not certain characters lived or died, or whether or not you did certain side quests all impact how these crises play out. Despite my issues with Mass Effect 3, which go beyond the ending by the way, I thought that they handled the conclusion to those conflicts rather well.

1. You’re correct, but it just sort of ties in to my broader point: Shepherd is the most important figure in the entire galaxy, and he for there partly by always being in the right place at the right time and partly by being exceptionally good at shooting.

2. The “3” are the geth, the quarians, and the rachni. With the rachni it really is just you stumbling upon the queen and arbitrarily deciding to free or kill her. While it’s true that saving both the geth and the quarians in the same game depends on other pieces being in place first; wheher

1. You’re correct, but it just sort of ties in to my broader point: Shepherd is the most important figure in the entire galaxy, and he for there partly by always being in the right place at the right time and partly by being exceptionally good at shooting.

2. The “3” are the geth, the quarians, and the rachni. With the rachni it really is just you stumbling upon the queen and arbitrarily deciding to free or kill her. While it’s true that saving both the geth and the quarians in the same game depends on other pieces being in place first; whether or not those pieces are in place still depends on other decisions Shepherd made. And even if you didn’t set things up correctly, events still just happen to conspire such that Shepherd winds up with the power to determine which species wins the decisive naval battle.

While I call this silly, understand I’m not really complaining about it; the agency this gives you is probably my favorite thing about the series. My broader point is that the previous poster here and other people elsewhere have claimed that inevitability and helplessness are large themes in the series, and this seems fundamentally backwards. If there’s a fundamental theme to the series, it’s that the universe generally bends to the will of Commander Shepherd’a guns and self-righteous shouting.

While it’s debatable whether or not this would have been satifying, the expexted ending to the series based on everything that came before would have been Shepherd giving an angry/inspiring speech about how irrational fear of synthetic life has already doomed the galaxy to eons of misery and genocide, and it’s time for the reapers to “get the hell out of our galaxy!” so that organics and synthetics can find their own path.

Ok, I’m way late to this party, but I just wanted to add something I didn’t see in my (admittedly quick) read of the comments section. No one has mentioned, that I’ve seen, the pragmatic limitations to carrying choices across three games. It’s all well and good to promise that choices have consequences that carry over, but in reality there is an absolute limit to how impacting those choices can be carried from game to game if you think about it.

ME1 has 3 major choice made near the end (Kill or save the council, ashley or kaiden dies, wrex dies or lives). Automatically that gives you 9 options (and that’s only if you ignore all the smallter stuff) going into ME2. ME2, with its “anyone can die” mechanic plus the “destroy or purge the base” choice at the end, ups this number of permutations substantially, and again, that’s not even considering the smaller choices.

All this is to say that a) it’s not surprising that whether you kill or save the council has little bearing on the rest of the series, b) that when one character from ME1 dies, a replacement character fits neatly into the same role they would have occupied later and c) that only a few characters from ME2 would play major roles in ME3. The storytelling would become too branching otherwise. Bioware doesn’t have the budget has a vast number of permutations of possible deaths and endings, all feeding into the story of not one but two more games. It’s no shock that, in the end, all those choices had to boil back down to something more simplistic when all was said and done.

After all, Bioware (and EA) are businesses, Mass Effect is a very successful franchise, and whether you view this as cynical or realistic, they can’t design the next game if they have dozens or hundreds of vastly different, vastly personal endings to consider.

Well, yeah, it’s understood that BioWare and EA have time and budget constraints and not everyone is going to have exactly the type of pony that they want. And, you’re right, the game is enormously complex story-wise as it is (I think that there are something like 25,000 lines of dialogue, much of it redundant dialogue for each potential squadmate for each mission).

But, I think that some of the options can easily be divided into “high-calorie” and “low-calorie” options, in terms of being relatively easy to create and slot into the game. For example, in my comment below, creating a final boss fight with the Illusive Man could be a high-calorie option, depending on how difficult you wanted to make it, whether he had any unique powers, etc. It wouldn’t necessarily need to be that fancy, though, since the series doesn’t really specialize in final boss fights. (In the first game, Saren basically turns into a geth hopper, and in the second, Shepard beats the human-reaper larva with a few rounds of target practice under fire.)

The other parts, though? Basically a bunch of cut scenes, maybe with a few different dialogue options or alternative versions depending on surviving squad members, romances, etc. (I really wanted to see a bit in which it’s implied that Liara–assuming that she survived and was Shepard’s romance partner–is bearing his/her child.) All they needed was a better writer, really.

First, I have to say (because this is Overthinking It, after all) you’re wrong in suggesting that “destroying [the mass relay network] centuries earlier would have been even smarter”, because the knowledge of the Reapers, and how they used the Citadel and mass relay network, only came about less than three years prior to the events of ME3, and as the Citadel Council points out to Shepard, there’s a dearth of evidence to back up that claim. Second, there’s only one way known of destroying a mass relay (short of using the Crucible), and that’s to smash a suitably-sized asteroid into it, as demonstrated in the Arrival DLC, which has the side effect of destroying the solar system that it’s in… which, of course, includes the capital planet of every galactic civilization. And third, and this is pretty important, who says that the Reapers would be stopped by the destruction of the mass relay network? They still have FTL flight, and if it takes them centuries to reach every civilization in the galaxy, so what? Wiping out the Protheans took several centuries, and they weren’t stopped.

In the end, no matter what great themes Mac Walters and Casey Hudson were reaching for, it was simply a poorly-written ending. I like Lavanya’s comment above about it being “a ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ solution to a ‘Lord of the Rings’ problem.” Sneer if you like at the prospect of “Shepard stabbing Harbinger in the head with an omni-tool spike and sneering ‘Reap this,’ then being elected Queen of the Galaxy”, but part of the whole purpose of space opera–and don’t kid yourself, Mass Effect is definitely this, rather than hard or even mildly rigorous science fiction–does require a more personal involvement of the protagonist with the cosmos-shaking events of the story. Even if Shepard can’t make an omniblade big and sharp enough to gut Harbinger, she’s already had at least three personal conversations with these eons-old vast intelligences: Sovereign in ME1, Harbinger in Arrival, and the dying Reaper destroyer on Rannoch. There should have been a more emotionally satisfying final confrontation than an exposition-laden dialogue with the misty doppelganger of the heretofore-not-even-hinted-at sentience of the space station. (Just as there should have been a final boss fight with the Illusive Man, because, come on, by the end of the game I wanted to punch him in the face even more than Kai Leng.)

What would have been a fairly satisfying ending, IMO, would have been a clearer choice between an ending which leaves Shepard alive, but possibly not resolving the threat of Reapers or other AIs coming back, and one that does resolve the threat, at the cost of Shepard’s life. (Sort of.) The first choice would have involved either the Destroy or Control endings. Choosing Destroy would still have wiped out not only the Reapers but also EDI and the geth (if they’re still alive), and also burnt out Shepard’s cyborg implants, leaving her permanently disabled. The epilogue would have had some discussion of whether or not there should ever be AIs allowed again; if some race decided to build them unilaterally (as the quarians did) and they found out that the organics wiped out all the synthetics, they might not stop at simply wanting their own planets as the geth did. If Control is picked, then Shepard becomes a version of David Archer from the Overlord DLC, always plugged in and always awake in order to maintain control over the Reapers. Yes, the Reapers are helping to rebuild everything, but a lot of people are still not trusting that they won’t slip control and start reaping again, with some races proposing that they build the equivalent of the quarians’ Migrant Fleet and get the hell out of this galaxy, just in case… and at the end of the epilogue, it’s suggested that Shepard, like the Illusive Man and Saren Arterius before her, is slowly being indoctrinated by the Reapers anyway.

The third ending would be called “Synthesis”, but would be nothing like the ending that we got with that name, because making every sentient being in the galaxy a cyborg is creepy at best and forcing everyone into the ME version of the Borg Collective at worst (because, really, how do you expect everyone to like everyone else just because they’re all cyborgs now, unless they’ve got some program that they’re all running that forces them to do so? So much for free will!). The synthesis is that Shepard controls the Reapers long enough to get them to upload all of the information about themselves and the civilizations that they’ve reaped, and then to destroy themselves without harming EDI and the geth. This is based on three pet theories of mine:

1) The Reapers retain all the memories of every being that they’ve assimilated. It’s the only real reason for the way that they’re created, which involves the physical breakdown and incorporation of entire people, as seen in ME2. The result of this, however, would be that they also contain the memories of being assimilated, and therefore the anger, pain and terror of countless people. Which leads to:

2) Indoctrination isn’t for the Reapers’ victims; it’s for the Reapers themselves. Indoctrinating dupes such as the Illusive Man and Saren is just a side-benefit, and probably not even really necessary, since they’ve been shown to be numerous and powerful enough to reap through sheer force. Plus, the indoctrination field is pervasive enough so that people can still be affected by it when they’re in a Reaper that’s been derelict for millions of years. The Reapers can’t be allowed free will, because otherwise they’d commit suicide. This would mean that the Control option really wouldn’t work in the long run, and the sooner that the Reapers could be disposed of permanently, the better.

3) This is the one that’s the biggest leap: The Crucible has a lot more to it than meets the eye. It is possible that the Protheans could have battled the Reapers for several centuries, yet failed to complete the Crucible, a task which seems to have taken the Alliance a few weeks, at most, but it’s extremely unsatisfying from a storytelling perspective. The real reason why the Crucible (which, we found out in ME3, is really the work of countless civilizations, and not just the Protheans) hasn’t been used until now is that a) most of it is in dark space (which I’m redefining as not being between galaxies, but being an adjacent dimension, a la subspace or hyperspace or whatever), and b) it’s been building itself for millenia; the “Crucible” that the Alliance has been building is the proverbial tip of the iceberg, an interface between the dark-space portion of the Crucible. Which is, by the way, a Death Star-sized computer, capable of hacking and taking over the Reapers; it’s not some giant mass-effect cannon. It can be used in a crude fashion, either to destroy the Reapers or (temporarily) take them over, but to be able to do what I outlined above, the operator has to have a deeper connection: they have to upload their consciousness to the Crucible, not only to control the Reapers without becoming indoctrinated by them, but to act as a permanent guardian for the data that they download from them, sharing it with the sentient races of the galaxy if and when they’re ready for it. Which leads me to the last thing:

4) Shepard is the Catalyst. It’s not Casper the Friendly Ghost, aka the Leviathans’ Big Mistake. Shepard’s a cyborg and she’s able to make the connection, have some dialogue with Harbinger before she collects their Harvest and sends them all into the various suns that they’re close to, but Shepard’s body can’t take the stress of interacting with the ginormous darkspace computer and she dies and is found with her hand resting on Anderson’s. Big space funeral, and the end scene is of her, Anderson, and everyone else who’s on the Normandy’s memorial wall setting off to have virtual adventures throughout the Crucible’s cyberspace. (And maybe a post-credits stinger showing the future residents of the galaxy–I’m thinking a vorcha, some insectoid version of the geth, and a descendant of Conrad Verner’s whose part of the Church of the Shepard–consulting with a holographic Shepard about the latest menace to the galaxy, a la Vigil on Ilos.)

And that, ladies and germs, is how you overthink things in my part of town.

Spoilers for Hyperion

The Hyperion and Mass Effect connection is interesting; I’m glad that you pointed it out. I think the fact that the Reapers also give eternal life/ eternal damnation just like the crucifixes is another parallel. There would probably be more if I spent some time thinking about it. Neat.

IMHO Mass Effect is a great work of narrative if you consider the Shephard (a.k.a. the player) “Hero’s Journey”:

The opening of the first game shows a worried Shepard looking over a peaceful Earth while the Udina/Anderson voicover asks: “What about Shepard? … Is that the kind of person we want to protect the galaxy?”.

After a three-game struggle, the words of the Stargazer (voiced by Buzz Aldrin and culpably cut in the extended ending) finally close the circle: this was the Shepard’s story, now a Legend passing from one generation to another as a message of hope, understanding and exploration.

It’s simple, neat and beautiful.

(All amplified at a magnitude because you’re earing this from the voice of a REAL astronaut)

The main plot of ME, on the other end, is goofy at best: ME1 is simply a chase, the second a series of recruitments and the third another recruitment trip, this time on planet scale.

Many words were written attacking and defending this or that plot hole but IMHO, many missed totally the point of the whole story.

I’ve finally finished this game yesterday – what the conversation with the Catalyst reminded me most of is the end of the Matrix Reloaded. Many cycles have passed with war with the Reapers but Shepard is the Neo of this one, who has the chance to reboot humanity and restart the synthetic/organic conflict but under the already dictated parameters of the Catalyst/Architect. And then at the end everyone potentially lives happily ever after because Shepard neutralises the evil with her death just as Neo does in the Matrix Revolutions.

I can’t remember what happens to the TechnoCore at the end of the Endymion Cantos, does messiah-girl defeat it with her fiery crucifixion? I love Fall of Hyperion, but I found the two Endymion books a bit too nice, in some ways, although there are some brilliant moments.

Also, I’m sure I’ve made a Hyperion Cantos joke on the podcast, but I’ve been on very few if any with Perich, so no-one got it.