Lee

You’re all familiar with the Prisoner’s Dilemma, right? Can we apply this famous game theory thought experiment to everyone’s favorite prisoner du jour, Jean Valjean, aka Prisoner 24601?

Fenzel

The game with the bishop and the silver could be diagrammed either in a tree structure or in a matrix, depending upon whether you run the moves as sequential or simultaneous.

I’m a little rusty, but it would be possible to speculate on a mixed-strategy equilibria, adjusted for the probability of JVJ getting caught.

It’s generally not going to be a prisoner’s dilemma, since the bishop gets to see Valjean’s move before making his own, but it might be possible that it works out that way for certain utility values of silver and salvation.

Stokes

There’s a better one right there in “Who Am I?”

If I speak, I am condemned/ If I stay silent, I am damned!

Valjean has two options: he can admit that he’s Jean Valjean, or he can be quiet and let the other guy take the fall. If he lets someone else go to jail for his crime, he goes to hell (which is an infinitely undesirable outcome — this stuff gets weird when you throw religion at it). On the other hand, because he’s a job creator and his workers depend on him for their livelihood, speaking up isn’t a totally moral action either… and of course he’d rather not have to go on the run again.

Now, the guy falsely accused of being Valjean (henceforth Pseudo-JVJ) isn’t even playing the game. He has no action to take. But there is another player, sort of, which is the whole apparatus of the law and the courts. In the film version, Valjean busts into a courtroom where Pseudo-JVJ is being sentenced. The judges and lawyers aren’t making a choice exactly, but presumably they at least have the option of doing their job well enough to avoid convicting an innocent man.

Now, the guy falsely accused of being Valjean (henceforth Pseudo-JVJ) isn’t even playing the game. He has no action to take. But there is another player, sort of, which is the whole apparatus of the law and the courts. In the film version, Valjean busts into a courtroom where Pseudo-JVJ is being sentenced. The judges and lawyers aren’t making a choice exactly, but presumably they at least have the option of doing their job well enough to avoid convicting an innocent man.

There are some reasons why they might not want to do this — presumably they’ve got 19th century French Clarence Royce pressuring them to get their numbers up — but again if we throw religion into the mix, they are damning themselves somewhat by sending an innocent man to jail. And again, this means that the downside of letting the man go to prison is a much bigger than the downside of letting him go free. The unambiguous existence of God within the narrative is a doozy of a force multiplier.

It’s still not a classic prisoner’s dilemma. The courts doesn’t know that Valjean is out there, so they can’t take his actions into account; also, they don’t know for a fact that Pseudo-JVJ is innocent. (When I’ve seen the musical done live, they sometimes stage it to suggest that Javert does know both of these things. But we’re basing this on the film.) Nevertheless, it has some of the same features as the prisoner’s dilemma, especially if (like me) you tend to think of the morally right choice in the prisoner’s dilemma as staying silent — honor among thieves and all that. The prisoner’s dilemma has the following outcomes:

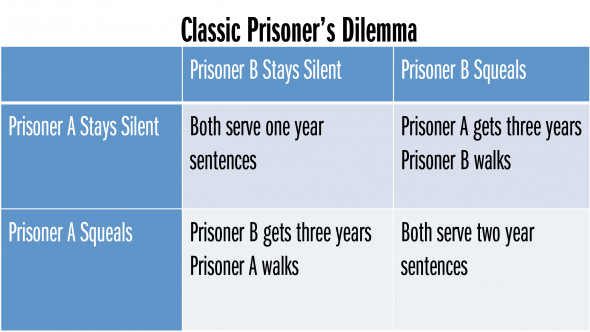

- Prisoner A and prisoner B both do the right thing, keeping their silence: both serve one year sentences.

- Prisoner A stays moral, but prisoner B squeals like the rat he is: Prisoner A gets three years, prisoner B walks.

- Prisoner B stays moral, but prisoner A sins: Prisoner B does three years, prisoner A walks.

- Both prisoners do the wrong thing, both serve two years.

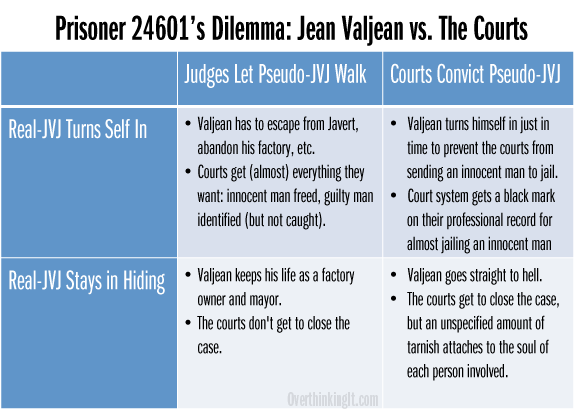

Valjean vs. the courts is similar, but not quite the same.

- Valjean and the courts both do the right thing: the judge lets Pseudo-JVJ walk, and then the real Valjean turns himself in anyway. Valjean gets hurt about as much as he does in the actual plot (he has to escape from Javert, and abandon his factory, etc.) The courts get everything they want — this is optimal for them.

- Valjean turns himself in just in time to prevent the courts from sending an innocent man to jail. (This is what happens in the play.) Nobody goes to hell, but the court system gets a black mark on their professional record — almost convicting an innocent man isn’t the kind of thing that gets you promoted.

- Valjean stays in hiding, but the courts do their freaking job and let Pseudo-JVJ walk. Valjean’s outcome is optimal. The courts don’t get to close the case, but this is less embarrassing for them than the previous outcome.

- Valjean stays in hiding, the courts convict Pseudo-JVJ. Valjean goes straight to hell, not passing go, not collecting 200 dollars. The courts get to close the case, but an unspecified amount of tarnish attaches to the soul of each person involved.

Interestingly, only the courts have a clear best action. If Valjean comes clean, they should do their job right to avoid embarrassment. If not, they should do their job right to avoid potential damnation. (And both of those potential outcomes should motivate their actions in every case they try, regardless of how much information they have.) Jean Valjean’s best action depends on what the courts do… but if he assumes that the courts are rational, then he can also assume that they will be moral, and therefore he should rationally stay silent.

And yet in the actual plot, it never occurs to Valjean for even a hot second that the courts might do the right thing! This is makes total sense: he’s seen the courts from the inside, and listened to Javert’s little statement of purpose at least twice, so he can pretty safely assume that they will convict an innocent man given the chance.

The clear implication for public policy: if your criminal class is basically comprised of saintly and rational guys like Jean Valjean, you want to make your legal process as senseless and brutal as possible. Otherwise, they will assume that you’re going to do the right thing, and won’t turn themselves in in these sorts of situations — which, if you have a senseless and brutal legal process, are going to occur pretty frequently.

Adams

There’s another player in the game, albeit before the Courts get involved – Javert. When he suspects JVJ, he has a dilemma of his own because of the high risk to him of being wrong, given Monsieur Le Mayor’s status. His payoffs for being right (A career boost for detecting an escaped felon and the satisfaction of seeing justice done) while substantial, are significantly outweighed by the payoffs of being seen as wrong (or, even worse, being actually wrong – at least how I read the movie, Javert’s sense of justice causes him to be genuinely distressed at the idea of accusing an innocent man – though as you say, there are a few ways of reading this).

There’s another player in the game, albeit before the Courts get involved – Javert. When he suspects JVJ, he has a dilemma of his own because of the high risk to him of being wrong, given Monsieur Le Mayor’s status. His payoffs for being right (A career boost for detecting an escaped felon and the satisfaction of seeing justice done) while substantial, are significantly outweighed by the payoffs of being seen as wrong (or, even worse, being actually wrong – at least how I read the movie, Javert’s sense of justice causes him to be genuinely distressed at the idea of accusing an innocent man – though as you say, there are a few ways of reading this).

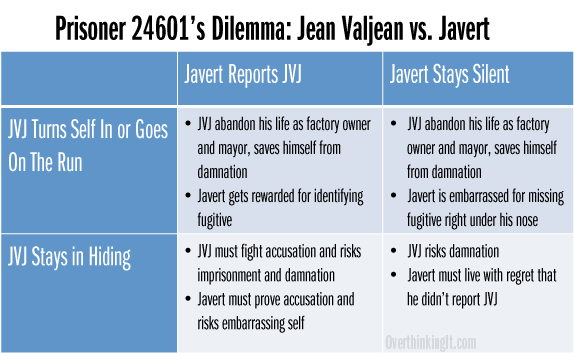

So at the point that Javert has identified JVJ, and JVJ is fairly sure that he’s been caught, there’s a bit of a game going on. Javert has the choice either to stay silent or report him; JVJ has the choice to either stick it out or run (or turn himself in, but running serves essentially the same purpose). Before he knows about the innocent man, the stakes are different than otherwise.

I’m not quite sure how that shakes out as a Prisoner’s Dilemma. From a strictly rational perspective, Javert’s best move is quite possibly stay silent – it’s not like JVJ is Osama bin Laden, while he’s a wanted man there’s no one that’s going to fault Javert for not catching him (though there’s the possibility that JVJ will be caught down the road and Javert will be in trouble for having him under his nose the whole time).

Stokes

Remember, Javert’s sense of justice is so exaggerated that when he’s eventually presented with incontrovertible evidence that he’s been behaving unjustly, he flat out kills himself. If he knows he’s wired that way, then his rational choices have to be adjusted accordingly. (But then you end up with Javert’s rational mind is playing games against his masochistic and irrational superego, which is kind of weird…)

Lee

Here’s my interpretation of the JVJ-Javert Prisoner’s Dilemma:

The “optimal” outcome for both is in the top-left corner; JVJ does the right thing and saves himself from damnation (even though he has to go on the run), and Javert performs his duty properly. The least favorable outcome for everyone is the bottom-right corner. It’s a stalemate in which JVJ stays silent but risks damnation and lives with the guilt for the rest of his life, and Javert doesn’t perform his duty and regrets that he didn’t report JVJ when he had him right under his nose.

You know, I really didn’t like this movie, but I’m glad it gave us this opportunity to talk about game theory. Thanks, Les Misérables.

Victor Hugo’s (the author of the book that the play and movie are based on)

inspiration for JVJ and Javert were in fact a single person.

a former convict that due to politics of Napoleon and stuff would up being a part of the law enforcement.

and even with God in the mix, if it was Utilitarianism (“the greatest good for the greatest number of people”)

JVJ can EASILY choose to remain silent. The pseudo-JVJ vs. the multitude of workers that he employs.

Stokes’s formulation implies that the most-negative outcome for JVJ (eternal damnation) is partially dependent on the actions of the courts. So if he stays silent, there is a possibility that he will be neither condemned nor damned.

But from JVJ’s point of view, his choice leads directly to one of those two outcomes, independent of others’ actions. That’s why he uses the logical form of simple implication “if…then” rather than conjunctive implication “if…and…then”. From the religious perspective, he would say that his damnation comes from allowing an innocent man to unwillingly face condemnation in his place, regardless of whether that man is actually condemned.

To those of you interested in Game Theory, I do hope you’ve seen this game show finale:

http://youtu.be/S0qjK3TWZE8