Damn Yankee?

[Correction: the tables and statistics have been updated to accurately reflect the 34 states that were in the Union and Confederacy at the start of the Civil War.]

The movie Lincoln is, by any measure, a hit with both critics and fans. According to Rotten Tomatoes, 90% of critics give it favorable marks, it’s slated to pass the $100 million mark at the box office this weekend, and IMDB users give it an 8.4 rating. Even the hard-to-please OTI podcast panel was unanimous in its approval of the movie.

But is the movie widely loved across the United States? The movie portrays the Confederacy unsympathetically and places the slavery issue front and center. In the South, Confederate apologists have spent 150 years trying, to varying degrees of success, to place the Confederate cause in a positive light, one that emphasizes states rights and Northern aggression and downplays slavery and racial animosity. (One example of this movement is the 2010 proclamation of “Confederate History Month” in Virginia which made no mention of slavery while calling on Virginians to “understand the sacrifices of the Confederate leaders, soldiers and citizens during the period of the Civil War.”) It’s hard to say how prevalent these views are, but they certainly exist in the former Confederate states. And if they do, it’s not much of a logical leap to suggest that audiences in these states might not be particularly enthusiastic for the movie Lincoln.

If you have a rebel flag iPhone case, you might be a redneck. And you might be less likely to see the movie “Lincoln.”

Can we prove this quantitatively, though? I scoured the Internet for state-by-state box office statistics, but came up empty. So lacking those numbers, the answer is no, we can’t. But we can try to use proxies like Google searches to gauge the differences in popularity of the movie Lincoln among US States.

I used Google Trends to return state-by-state search statistics from September 9 to December 7, 2012. The search term “Lincoln” was too ambiguous; it resulted in too many false positives in states like Nebraska and Rhode Island that have prominent cities named “Lincoln.” So I used the name of the starring actor, “Daniel Day Lewis,” as the next best proxy. Granted, this is an imperfect method at best, and a misleading one at worst. But lacking any other state-by-state data on movie popularity, it’s the only option on hand, so let’s roll with it.

Statistics of the DDL, by the DDL, for the DDL.

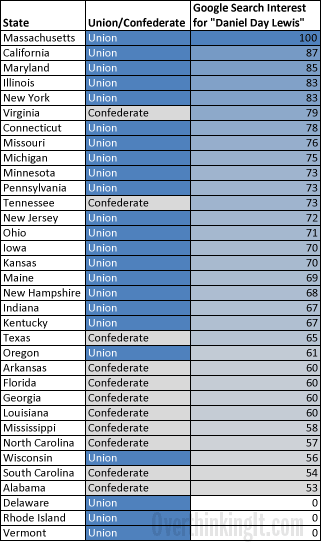

First, let’s take a look at the state-by-state results for “Daniel Day Lewis.” The following table shows Google’s normalized calculation of search popularity by state, relative to the state with the most (normalized) search activity. I limited the results to just those states that existed at the time of the Civil War:

Updated 12/10/2012

Note that just because Delaware, Rhode Island and Vermont show up as “0” on this chart doesn’t mean that anyone in those states was searching for “Daniel Day Lewis” during the time period. It just means that the volume of searches, relative to the overall search activity in those states, was too small to register in Google’s calculation.

Eyeballing this chart, it’s pretty clear that Union states dominate the upper half, while Confederate states dominate the lower half. The aggregated numbers support this assessment: excluding Delaware, Rhode Island, and Vermont, the average value for Union states is 74.20, while the average value for Confederate states is 61.73.

Statistics of the vampire, by the vampire, for the vampire.

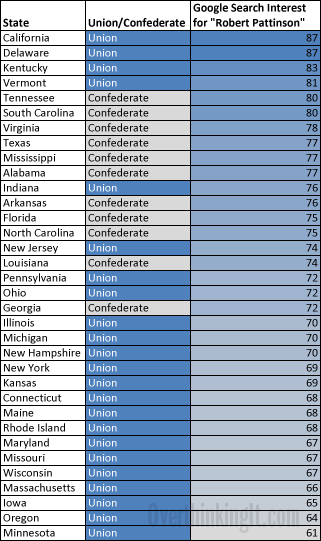

Based on this broad assessment, there seems to be a clear regional difference in Google searches for “Daniel Day Lewis,” but is that just because people in Northern states are more likely to search for leading actors in their movies? To test this, I applied the same methodology to the actor Robert Pattinson of Twilight fame to see if the same geographic disparities existed for this less politically charged topic:

Updated 12/10/2012

In this case, the Union average is 70.25, while the Confederate average is 76.45. Obviously, it would take a more thorough examination of state-by-state search habits to say anything definitive on this, but for the scope of this article, let’s proceed with the idea that Union states are searching more for “Daniel Day Lewis” than Confederate states.

We could end the analysis on that note, but I did think of one other way to assess the degree to which the former Confederate states are adverse to Lincoln, and that is of course, slavery. The hypothesis is that Confederate states that had larger slave populations had more to lose from the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment, and that lingering animosity in those states translates to less interest in the movie Lincoln.

We could end the analysis on that note, but I did think of one other way to assess the degree to which the former Confederate states are adverse to Lincoln, and that is of course, slavery. The hypothesis is that Confederate states that had larger slave populations had more to lose from the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment, and that lingering animosity in those states translates to less interest in the movie Lincoln.

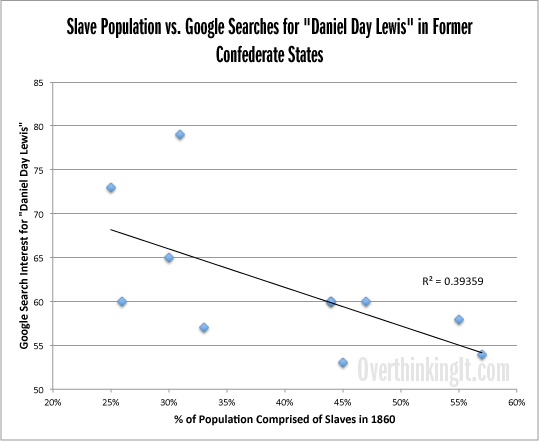

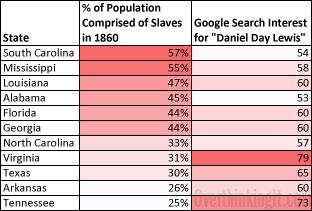

A basic linear regression that plots the percent of populations comprised of slaves and Google searches in “Daniel Day Lewis” reveals a negative correlation between the two:

In other words, the more slaves there were in a former Confederate state, the less searches there were for “Daniel Day Lewis.” Here’s the data for the graph above in chart form:

I should be very clear about the conclusions that we can and can’t make from this data. We can say that state-by-state slave population levels in 1860 do have a negative correlation with state-by-state Google search interests for “Daniel Day Lewis.” Without additional data, we can’t take the logical leap and say that this data proves that states with higher levels of Confederate sympathies are less receptive audiences for the movie Lincoln, although the data that we do have on hand is consistent with such an idea.

So where do we go from here? Obviously, if we had state-by-state box office numbers, we could answer this question definitively, but without it, there’s still plenty to talk about. Was my methodology sound? Is there a better proxy, Google or otherwise, to measure state-by-state interest in a movie? Is there a simpler explanation to all of this–that Lincoln is targeted at a higher-income audience, and that such an audience is less likely to be found in the South by nature of per-capita income and education levels? If you live in a former Confederate state, do you have anecdotal evidence of Lincoln’s popularity, or lack thereof? Sound off in the comments, for you are the readership of Overthinking It, clothed in immense power!

Have you tried simply controlling for income? I’ll admit, that’s not technically sound because of the high degree of correlation between present-day income and 1860 slave %, but it should give you a first impression. If it looks promising, you can do a 2SLS.

I am not sure that is necessarily very informative for these sorts of low-cost purchases. It would probably be more informative to control for the number of movie theaters or theater seats in the state, since that would give some indication of the overall popularity of watching movies.

I’m an AP United States History teacher at a mostly-white school in the Deep South, and I took kids to see “Lincoln.” They loved it. That said, do I know people who still try to argue that Lincoln was some kind of tyrant, that slavery didn’t cause the Civil War, and that the South has been unfairly picked on for its whole history? Sadly, yes.

Maybe the moral here is that the up-and-coming generation is finally going to leave a lot of that nonsense behind.

http://www.xkcd.com/1138/

Not sure how this fits, since there are obvious differences in the Rob Pattinson and Danny D. Lewis results (the comic implies that the results should be the same).

Unless you’re saying this is proof that the answer to the titular question of the post is yes?

(Also, how is Pattinson not yet included as a word in my browsers spell check?)

The data is normalized for relative search volume.

“Are” normalized. Sorry.

http://www.google.com/trends/explore#q=daniel%20day%20lewis%2C%20robert%20pattinson%2C%20twilight%20movie&geo=US&cmpt=q

Pick Metro in Regional Interest section and flip through the tabs. Compare with http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:USA-2000-population-density.gif . Also note the paucity of searches for Daniel Day Lewis in general; most metro areas score out at 0. That means a relatively small overall sample size with more noise accordingly.

My intuition is that search volume scales at a greater than linear rate with population, meaning a linear correction is insufficient.

Hate to nit pick, but Nebraska and New Mexico were not states during the Civil War. Nebraska was admitted in 1867 (slight mistake) and New Mexico in 1912 (not so slight mistake).

Thanks for pointing this out. I’ll make corrections to the charts and numbers soon.

The charts and numbers have been updated to accurately reflect the states that existed at the start of the Civil War. In addition to Nebraska and New Mexico, I also removed Nevada, which wasn’t admitted until 1864, since I originally excluded West Virginia, which wasn’t admitted until 1863.

Note that this actually slightly increased the difference in averages between Union and Confederate searches for DDL.

Searching “Daniel Day Lewis” seems like an unnecessary complication to your analysis. Why not just search for “Lincoln movie” in quotes? The results seem to mirror yours, but I think that’s a more likely search for people interested in seeing or learning about the movie.

As to false positives, looking at the Nebraska data over time, the relative search volume is zero in September, and peaks November 18-24 (right after the release) so I think it’s safe to say were only looking at searches for the movie Lincoln, as opposed to searches for movies in Lincoln, NE which should be more or less consistent over time (the year long data seem to support this, with the only spike in November).

Of course Nebraska isn’t in my analysis, but it’s a good check on the relevance of the data.

Some differences:

– Virginia is 100 (probably due to northern VA being suburban Washington, DC).

– Median average of Union (minus VT and DE with indices of zero) is 71.5. Median average of Confederate is 62.5. Almost the same but a little closer to each other.

I don’t know if this analysis (yours or mine) means anything (which is of course par for the OTI course). I would assume doing the same analysis for a series of big movies and comparing the results would highlight any stark differences.

“Lincoln trailer” might also be an informative search.

Alternatively, could you search for “Lincoln showtimes” or similar?

But what about Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter???

I just learned via Wikipedia that Mississippi’s state flag prominently features the Confederate battle flag, and that voters chose to keep it in a 2001 referendum by a 64-36 margin.

Not that my point about ongoing Confederate sympathy was under contention, but I thought this made a powerful point about the enduring legacy of the Confederacy and the Civil War in the South.

The confederate battle flag is also an ongoing issue in South Carolina. And where I grew up there’s a line of clothing and products recognizable because they put the flag on *everything* (including some truly offensive stuff. Like the shirt that depicted slaves picking cotton under the banner “I wish I was in Dixie”). Here’s proof that it’s real, since as an adult living in NYC I learned that this sounds totally insane outside of the South. http://dixieoutfitters.com

But as much as I hate Dixie Outfitters and strongly believe we should stop with the damn flag already, I will say that for the people who purchase the products they have almost nothing to do with the Civil War. They are trying to use it as an emblem of Southern heritage, and will act as if you are deliberately and unreasonably misconstrue their meaning if you bring up the Civil War. It’s “history, not hate” and people want it to represent pride in one’s home, loyalty to family, self-sufficiency, as well as conservative political messages often imbued in the “Don’t Tread on Me” flag. (That flag was designed by a Charlestonian during the Revolutionary War. So maybe we’re inordinately into communicating with flags here).

That is not to say that the events of the Civil War don’t still heavily influence Southern culture. They do, in very powerful ways. But effects are pretty complicated. I’m not really sure “Confederate sympathy” is the right term, because you’d be hard pressed to find a lot of people who would say, “I think slavery was the way to go, succession was a good call, and that Lincoln fella got what he had coming.” The contentions about the Civil War tend to be about memorialization and definitions, and the broader cultural effects are so deeply embedded that they would difficult to recognize as such.

What I’m trying to say is that I’m sure a lot of people in Mississippi who voted in favor of keeping the flag also went to see Lincoln and loved it, and don’t recognize any dissonance there.

FYI, using “Lincoln movie” as the search term, Mississippi gives by far the lowest search popularity, 45, with the next lowest being Florida at 56.

In Montgomery Alabama across the street from the state capitol building is the ‘Confederate White House’ from when the capitol of the Confederacy was moved from Richmond. They still fly the CSA flag over this tourist destination.

…which is ironically at the corner of Washington and Union Street.

I saw Lincoln in Charleston, SC which is about as Civil War remembering deep South as it gets (home of “Great Nullifier” John C. Calhoun who defended slavery as an absolute good; Fort Sumter, where the first shots were fired; and many plantations. The theatre was crowded and the movie was extremely well received. I went with my grandparents and, judging by the apparent age of other theater-goers that day, a lot of other peoples’ grandparents too. I didn’t hear any tutting about the War of Northern Aggression or gasps of disapproval about the late unpleasantness. For what it’s worth, my grandmother was moved to tears by the opening scene, my aunt tried to get us to leave before the end so we could stay happy, and the passage of the amendment got a round of applause.

Robert Pattinson, what with his heartthrob, gossip headline status seems like someone who would be the subject of a lot of Google searches unrelated to his movies. It also seems like the Lincoln target audience is probably older than the Twilight target, and maybe less likely to use Google. Maybe this is actually an indication that older southerners are less frequent internet users than older yankees. Pretty much everyone we discussed the movie with after our showing had read about it in the paper.

It may also be a rural vs. urban thing. Things tends to be a lot different in southern cities than southern rural areas (as well as northern cities and northern rural areas). So I am not really sure the events in any major southern city could be taken as representative of the state population as a whole.

This might be underthinking it, but I wonder if it might have more to do with the cultural difference between Oscar-bait movies vs. blockbusters. If one assumes most of the union states are associated with a more “elitist” intellectual subset (to stereotype a bit) and confederate states are populated with less educated (again stereotyping) populations, then it would make sense that union states would be more likely to see a prestige period piece. Rather than comparing “DDL” searches to “Robert Pattinson,” I’d be curious to see the results comparing, say, the star of “Silver Linings Playbook” or “People Like Us,” which are maybe more similar to Lincoln in terms of being “intellectual, Oscar-ish” kind of movies.

wouldn’t movie gross by state (divided by pop) be a much more direct and informative statistic?

Well, yes, but the whole point of this article was that the numbers for movie gross by state are not available. Hence the use of Google search volume as a next-best-but-imperfect proxy. If you have any idea how to find those state-by-state movie gross numbers, please do let me know!

An r-squared of (basically) 40 is a result that’s not the worst, but could use some improvement, so some more control variables would probably help the goodness of fit of the model, as well as give you some other contributing factors to which you can compare your key independent variable (to see if it’s more important and whatnot). What’s the p-value, and is it significant at any standard levels (.1, .05, .001, etc.)?

I think someone above suggested it, but how about movie theaters per state? That may work better if you were able to access state-by-state data on box office intake, though.

I’m not sure exactly where it’s at, but I know my officemate (Mike) uses measures for internet access by state in some of his research- that may be a good control variable, as well. States with higher internet access would probably have higher search rates, after all, which could skew results.

Also, what about data on Civil War reenactments? Something to account for the number of people acting in them (not tourists), how often they happen, or somesuch.

Are people in Confederate states less likely than people in Union states to go to Lincoln because the movie deals with slavery?

For this purpose, Twilight is a pretty terrible movie to compare with Lincoln. Do Confederate states search more for fantasy or romance vs historical dramas compared to Union states? More for massive moneymakers vs less popular movies? More for critically snubbed movies vs critically acclaimed movies?

I compared Lincoln with The Social Network. Both are critically acclaimed, both are biography/dramas, both made about the same amount of money over the first few weeks. Similar to what you did, I compared searches for “lincoln movie” in 2012 with searches for “social network movie” in 2010. I used “lincoln movie” instead of “Daniel Day Lewis” since it is more direct, Nebraska isn’t included in the data, as andre the chemist notes searches for “lincoln movie” seem to be mostly for the movie, and the numbers for each search are pretty close either way. I found a similar result to what you found. For The Social Network 5 Confederate states were in the top half of google searching, 6 in the bottom. For Lincoln only 2 Confederate states were in the top half of google searching, 9 in the bottom and most of those near the very bottom of the list.

The tables:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0ApWESg83GIANdExkUVZ0OWozS3gzSzEzVjdsTmV3MFE#gid=0