Hogwart’s School of Wizardry and Witchcraft is all about teaching young magicians the laws of magic – say this spell, and you get that result. Magic may allow you to defy the normal rules of life, but you can never escape all rules. In any fiction involving magic, there are always laws or rules that constrain what you can do with magic – Aladdin can’t wish for more wishes and we are told that even Albus Dumbledore can’t conjure up gold from nothing. Without rules, the conflict is too easily solved and the story is boring.

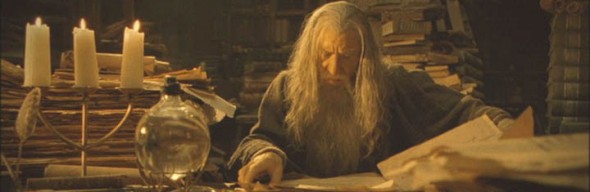

Because it’s so bound up in these rules, the treatment of magic in fiction can be compared to how we deal with the more mundane laws of black letters on white pages. Magicians and lawyers are similar in that they rely on nothing more than their ability to turn words into power. They toil over long lost tomes and puzzle over the meaning of baffling arcana to find that one turn of phrase or trick of logic that allows them to accomplish their goal. This transformation of language into power is scary and frequently seems craven or backhanded. It creates hatred and distrust among the general population for both the Wizard and the lawyer – until you need an incantation or a contract written. Magicians, like lawyers, are both the cause of and solution to all of our hero’s problems.

The first party to the second party owes the third party…I don’t understand ANY of this.

When we hear about the downfall of King Midas, it’s easy to imagine some lawyer behind the scenes, figuring out how to construe the wish “Everything I touch turns to gold” in the most evil way possible. Fiction is full of stories in which the rules of magic come back to bite someone, a single errant word bringing their entire plan to ruins. We hear those stories and are reminded of the “2 Million Dollar Comma” and our friend who lost his house because of an obscure clause in his mortgage contract. Words are slippery, tricky things, and magicians and lawyers both rely on mastery of them for power.

Our own everyday laws are based on a kind of magic. In the United States, when you’re being interrogated by a police officer, the phrase “I want a lawyer” has roughly the same effect as a magical spell. A particularly powerful incantation, those four words alone will both ward off the government employees threatening you with the death penalty and conjure up a different government employee that will do everything in their power to get you off scot-free. If the spell doesn’t work right away and the police ignore you, it induces amnesia at trial, making the court “forget” everything you said after invoking the right to an attorney.

Law is full of “magical” words and actions. Instead of waving a wand to seal a bargain, we sign our names, but if has the same “magical” effect of turning words on paper into a binding agreement. We don’t have “Avada Kavadra,” but a Judge saying “I hereby sentence you to death” has the same practical (albeit delayed) effect. Put the right people in the right room and have them all say “Aye” and a bunch of symbols on the page become binding law.

The “magic” of law is perhaps most apparent in the fiat money system. Money is valuable because the law says so. A dollar bill is valuable only because it was minted in a particular place and the right person waved a Federal Reserve Wand over it and said “this is money now.” Imagine that you know how to make a 100% perfect replica of a $100 bill. While you might be able to get away with spending that money, the law is very clear that the object you’ve just created is not worth $100. Even though it’s physically identical to a “real” bill, the fact that no one waved the government’s Legal Tender Wand over your bill makes it a counterfeit, regardless of physical properties.

It’s not surprising, then, that in fictional universes that make use of magic, magic often serves as a direct substitute for law. King Arthur’s kingdom didn’t have complex election rules or billion dollar elections – a magic sword just picks the right person. In Harry Potter, the marriage of Fleur Delcour and Bill Weaseley isn’t sealed with a state certificate and the signature of witnesses – they use a magical spell. Nowhere is the Magic-Law substitution more apparent than in the magical bargain – from Faust and Rumplestiltskin to Harry Potter and Pirates of the Caribbean’s Davey Jones, magical agreements drive the plot to many magical tales. Perhaps because it is the type of law that most of us encounter in our day-to-day lives, the magical-agreement-gone-wrong is one of the most common tropes in stories involving magic.

When you sign a contract, the only thing that changes is the threat of legal sanction for non-compliance – if the other side changes its mind, a piece of paper with a signature has no special powers over them. If you want to get compliance, you have to sue them and convince a judge that they broke the agreement, who will then order them to follow it, with various civil and criminal penalties attached. With magic, you can cut out the middle man and literally force the other side to comply with the agreement. The magical contract is typically portrayed as sacrosanct – in the Little Mermaid, Ursula’s contract with Ariel is so binding that even King Triton is powerless to undo it. In Harry Potter, House Elves aren’t bound to their masters with something as flimsy as a piece of paper and the threat of legal sanctions, or even as fickle as the threat of violence – House Elves are literally unable to resist their master’s commands, in the same way that they are unable to resist gravity.

Throughout the Wizarding World, magic is used as a substitute for traditional contracts and enforcement of agreements. When Hermione is worried about the other students telling Dolores Umbridge about Dumbledore’s Army, she doesn’t pull out Non-Disclosure Agreements and threaten to sue the other students if they don’t comply – she just hexes the parchment and the punishment for breaking the rules follows automatically. When Narcissa Malfoy wants to be sure that Snape is going to help her son, she doesn’t pull out a contract – she makes him take an Unbreakable Vow.

Guys, seriously, this would all be a lot easier if we just talked to my cousin, he’s a partner at DLA Piper.

The problem with magic substituting for law is that it’s not a very good substitute. Consider the magical will of Sirius Black. Just by reading it, the Order of the Phoenix can’t figure out what it means or whether they actually have ownership of their headquarters. Dumbledore has to conduct an experiment to determine if it’s binding or not.

Hermione’s “Dumbledore’s Army” contract doesn’t work because the people signing it don’t know what the consequences of breaking it will be. A Non-Disclosure Agreement would probably have been more effective, because such an agreement would have to spell out exactly what the consequences of breaking it will be. Lucius Malfoy is essentially tricked into losing control over the Dobby the House Elf when he hands him a dirty sock. While we cheer the result because of the parties involves, that’s not how normal labor relations do or should work – if you want to get out of a contract at your job, you can’t just trick your boss into signing a letter releasing you. Even if you did, no court would enforce it. In the Wizarding world, however, the laws of magic are also the laws – Malfoy has no contract to enforce with Dobby because up until that minute, he didn’t need one.

Magical laws are simply too inflexible for the replacement of textual laws construed by reasonable adults. In Goblet of Fire, Harry Potter is forced to compete in the Triwizard Tournament because the “rules” of the Tournament could be changed without the knowledge or consent of anyone running the Tournament– Barty Crouch., Jr. changed the rules by casting a spell on the Cup. Because the rules were fixed by a magical cup and not just a list of rules, there was nothing that could be done and Harry was forced to compete. Imagine if the Super Bowl decided that this year the offense could use 13 players instead of 11 because someone at the printer’s office fat-fingered the latest edition of the Rulebook. Magic gives you powerful tools to accomplish the goals of law, but it’s too inflexible and unforgiving to be a permanent substitute

Even worse, the substitution of magic for law also means an erosion of faith in black letter law. To someone who works with real magic every day, the magic of the law is mundane and unconvincing. How could you possibly explain to a Wizard that your $100 bill is real, and the pile of copies he conjured with his wand are worthless? Reliance on magical law necessarily decreases faith in – and hence the power of – the rule of law.

This has disastrous results for the magical world. The judicial system of the Wizarding World is a mess. At nearly every turn, rights are trampled, impromptu trials are held and innocent people are sent to Azkhaban. Voldemort is able to upend essentially the entire civil society in just a few weeks because the power of the Ministry of Magic doesn’t come from the collective will of the people, it comes from a bunch of guys with wands. This doesn’t start with He Who Must Not Be Named – in Order of the Phoenix, Fudge is ready to imprison Harry and then Dumbledore on the thinnest of pretexts, and is thwarted only by the sheer badassery of Albus Dumbledore.

The Wizarding World is still stuck on a gold standard of money in the 20th Century. One can only imagine the Weaseley’s would have a much easier time getting out of poverty if it weren’t for a massive liquidity problem. Harry is portrayed as being vastly wealthy and all of his gold is literally sitting in a vault. For the first 15 or so years of his life, it sat untouched, earning zero percent interest. The magical protections of the vault at Gringott’s keep the gold safe, but not nearly as safe as your money is sitting in a bank with Depositor’s Insurance – and you at least get a couple percentage points of interest while it’s there.

“Let’s see, 5% compounded annually for 12 years, comes out to….you bastards!”

Magical people spend their entire lives learning the rules of magic – at the expense of nearly every other pursuit. There are seemingly no novels in the Wizarding World, no English or rhetoric classes at Hogwart’s School of Wizardry and Witchcraft. The only words with any power in the magical world are the tiny subset that happen to have magical properties. Words that can persuade or words that move the soul get no attention. A Wizard would look at the Declaration of Independence at the National Archives and wonder what magical properties the paper is supposed to have, or what spell we were trying to cast with “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” No spell ever freed more slaves than the Emancipation Proclamation or moved more people to tears than Romeo and Juliet. Words should have power because we give them power, day by day and person to person.

How interesting that this article shows up just as I am reading “Three Parts Dead“, a book in which the parallels between magic and law are pretty explicit. In this world, magic is based on contracts between people, gods, and powers of the universe, spelled out in complex detail through the use of “Craft”. It can be sensed and understood by trained experts with a professional degree, but is too subtle and confusing for most laypeople to understand. The chapter I just read has a great depiction of what is essentially a magical EULA enforced upon entering a building (to paraphrase, “by entering here, the entrant is bound to do no harm to others while inside, where harm is defined as one or more of (a) … (b) …”), and a fascinating courtroom scene where a contract dispute becomes a wizard battle, where each party uses magic to demonstrate, manipulate, and reinterpret the terms of the contract. I can best describe the book as a combination fantasy novel and legal thriller. I’m thoroughly enjoying it… if you are interested in the intersection of magic and law, you should consider it a must-read!

1) You point out that Harry’s gold is earning zero percent interest, but the entire reason fiat currency needs to earn a return over the long term is that potential future inflation will make a set number of dollars (or whatever) worth less. You will lose money in a deflationary period, but trends tend toward inflation. Assuming that gold had been in a Muggle vault (in the US), it would be worth probably 3 times what it was at Harry’s parents’ death. That beats the silly 1% return of a savings account. Granted, we do not have consumer price index data for the cost of things in the magical world, but the idea that interest rates in bank accounts are even reasonably a sound investment is a misconception. A federally insured savings account at 1% interest would have lost money compared to gold in a vault, at least in the Muggle world.

2) You state that the terms of Sirius’ will are not specific enough, (which often happens to real wills), and Dumbledore has to resort to an experiment. I don’t see how this is necessarily much worse than having a bunch of people read it and try to interpret the wording; if a legal test could be settled without experienced jurists interpreting contract law but EMPIRICALLY, isn’t that a vast improvement?

3) Magical contracts compel behavior, as with the Goblet of Fire and the Unbreakable Vow. It is crazy that Harry has to compete because the contract was tampered with (which I guess is akin to inserting fine print you’re hoping no one will read). But there are also clearly loopholes to these contracts: Kreacher is bound to never leave Number 12 Grimmauld Place, but is able to interpret Sirius’ command to leave as literal permission to leave the dwelling and collaborate with the enemy. Similarly, Harry is compelled to participate in the Triwizard Tournament, but there is no reason to believe he cannot intentionally disqualify himself– he is nearly disqualified several times.

4) I also disagree that money is made magical by official sanction: that official power of the government derives from the people. Money is not imbued with that quality by the government, it is done so by convention of the people. No number of government treasurers can change the state of things when people collectively believe their government’s currency has become worthless and use something else as currency instead.

In regard to point 1) you’re assuming that gold has also experienced asset price inflation in the wizarding world as it has in the muggle world.

The Wizard economy would likely be very poorly off because it is apparent that Gringotts engages in no fractional reserve lending with its gold, although it must be engaged in some low leverage lending as it must be paying for all the very expensive security and employees somehow. This would mean loans for businesses or houses would be prohibitively expensive or conditional to attain, stifling the emergence of new competitors and stifling the chances of any family’s social mobility.

And for all that, if your vault is robbed Gringotts says “too fuckin bad we ain’t replacing it”

I don’t think we have enough data to conclude whether or not the wizarding world has experienced asset price inflation, or consumer goods inflation. I simply meant that without this data, there is no basis to conclude that a vault of gold is inadequate– the author’s suggestion of a savings account is wrong on two counts. First, that wizarding long-term inflationary trends necessarily mirror those of the Muggle world, and second, that a savings account is a good vehicle for preserving capital in the real world. I’m not assuming anything, I’m simply pointing out that the author has no basis for the wizarding financial recommendations he’s making.

Also, how is it apparent that Gringotts engages in no fractional reserve lending? The vaults themselves may be essentially safe deposit boxes as a courtesy for old wizarding families, there may be other general accounts that are used for such lending. Muggle-borns and wizards that marry Muggles still may need their own accounts. And presumably, Gringotts has to operate the Muggle/Wizard currency exchange.

Given that the bank appears to operate with a Ministry-sanctioned monopoly, if business or real estate loans could not be obtained by wizards/witches, something could be done about it. The US government goes to great lengths to ensure credit is freely available to those who need it so that the economy will continue to function (including bailing out institutions that engaged in really questionable behavior). I see no reason to believe that the wizarding world would be any different.

Spankminister: two things that i think point to the fact that the Wizard economy is rather dissimilar to our own. The first thing to keep in mind when thinking about Wizard economics is that, through magic, almost everything can be made and transported practically free. Yes, there are some things that can’t be “made” out of thin air, like food and gold, bu they can be multiplied ( though it’s never made clear if there’s a difference). I would argue that this means that there is probably never much inflation in the price of assets and commodities since it can just be made or multiplied for free. ( I’m assuming that Galleons and other official currenceis have anti-multiplying spells built in)

Second, there’s at least one instance that seems to indicate that there is a credit crunch in the Wizard world: George and Fred’s shop. When the twins want to open a brick and mortar version of their gag business (previously an owl-post order business) they bet their life savings on a Quidditch match and eventually borrow Harry’s Triwizard prize money. Why, i’ve always wondered didn’t they get a loan? They must have been of legal age if they could buy property. They also had an established customer base very near their desired locale and a set of products that had proven profitable. But I don’t remember anyone even mentioning that they apply for a small business loan.

“While you might be able to get away with spending that money, the law is very clear that the object you’ve just created is not worth $100.”

Actually, that is not the case. All the law indicates is that it is not a genuine $100 bill produced by the Treasury Department. If you give your counterfeit bill to a merchant in exchange for $100 worth of goods AND the merchant is aware of the fact that the bill is counterfeit but STILL provides you with said goods, your counterfeit bill was worth $100 after all.

Yep. Look up J.S.G. Boggs. It may not be currency but it still can be a medium of exchange.

“Money is valuable because the law says so.”

This is just incorrect. It’s true that you can’t print your own and pass it off as the notes printed by the Treasury, but then you can’t put fries in a box with a yellow M and pass it off as McDonald’s either. Trademarks are one kind of magic, yes, but not the kind that gives money buying power.

Money has buying power because *people believe it has buying power.* The shop owner accepts a $100 bill because she believes she can spend that $100 bill elsewhere (or deposit it in a bank and use her demand deposits for the same thing). Legal tender laws do not require any seller to accept the $100 bill as payment, nor do they prohibit the acceptance of alternatives like Euros or Ithaca Hours. Most people in the US won’t accept Euros or Ithaca Hours because they know most others around them won’t accept these forms of payment. If everyone around you thinks they’re money, though, you will too. And you’ll be right. In short, Money isn’t Magic; Money is a Fairy.

After my first comment being so negative, though, I should say good job on the post! The parallels are quite interesting.

I think I made a mistake in focusing on the money aspect so much – the relationship between magical enforcement of contracts and legal enforcement was really my main point, but I’ll address a couple of the complaints above.

1. My point with the money example was more on the value of the counterfeit bill than it is on the actual source of money’s value – we can argue semantics about where “real” money gets it’s value, but I don’t think it’s philosophically or legal controversial to say that a bill made in the Federal Reserve has a very different status than an identical bill made in my basement. You may still be able to GET $100 worth of goods for the money, but the bills still aren’t identical objects – if the government finds out you’re passing off your bill as real, you go to jail, regardless of it’s physical properties.

That was my main point – that the force of law gives very different status to two physically identical objects, which is a “magical” effect.

2. My point wasn’t that a savings account is necessarily a better investment than gold – though I will point out that canonically, Harry was born in 1980, and gold nearly halved in value between 1980 and the middle of the 90s. That wasn’t my point though – it’s not like the executor of the Potter estate decided that gold was the best way to invest Harry’s money.

My point was that the LEGAL protection of Depositor’s Insurance is stronger than the MAGICAL protection of vaults, dragons and goblins. Harry’s money can be stolen because it’s a physical object sitting in a vault – my bank account can’t be stolen because it’s just a legal agreement between me, the bank and the government.

My larger point about money is just that the Wizarding world’s reliance on magic has essentially blinded them to alternatives – they’re stuck on the gold standard not because they’ve decided it’s the wisest policy, but because something like fiat currency would simply not make any sense to them.

I’m trying to remember any money ever changing hands by any characters and I don’t think so. While Hogwart’s may be an all-inclusive sort, Diagon Alley certainly isn’t. My feeling that the economy is mostly made up of barter, talent for goods. As you get more powerful the equation gets skewed and talent allows for accumulation. After a while you become your own federal reserve backed by Gringott’s name. Harry is wealthy because his chop is backed by real gold, underwritten by Gringott’s signature of authenticity.

What this means is that though Gringott has power, it’s limited, doesn’t work in the Muggle world, and won’t be politically a force. Inflation doesn’t enter the picture either. Either you have real assets on deposit or you don’t. Spend/assign your chop to more things than you can use your talent for and your assets start getting used up by on demand accounting. What Gringott’s brings to the table is accounting accuracy and security. Fairly elegant and workable as long as the society is relatively small. You can’t process too many transactions that way and still stay accurate.

I wonder what the copyright rules are on spells? Hermione is probably going to be the wealthiest of them all since she comes up with new ones all the time which would be where the value lies.

Since this economy is talent/labour based, inflation, counterfeiting, fractional reserve lending et. al. won’t be an issue.

They do use money (Galleons, Sickles and Knutts if memory serves), but my sense is that the medium of exchange is actual physical gold – Harry has to go to his vault in Gringott’s to get his money. He doesn’t get a gold-backed Gringott’s note – he gets actual pieces of gold. As far as I know, at no point in the series does anyone use paper currency of any kind.

I realize I’m making a leap in assuming that the Wizarding world hasn’t even considered fiat currency, but I think it’s the logical assumption to make. There’s no evidence anywhere that there’s anything resembling a finance ministry, there’s no use of paper currency or other kind of investment instruments. The best schools in all of Wizard-dom have no economics or mathematics courses – who in the Wizarding world would even have the ability to MAKE a policy determination behind currency.

It goes back to my original point – a society that relies entirely on magic has no REASON to get into all of these legal debates. It’s why the magical world is so lacking in traditional muggle technology (they don’t watch TV, use telephones or have access to the internet). A Wizard sitting in physics class would laugh in the professor’s face when he started talking about Newton’s laws, in the same way that they’d laugh at you when you tried to explain why people give any value to pieces of paper with pictures on them.

Re: Depositor’s insurance, you’re simply trading one set of uncertainties for another. If the government were to become insolvent or overthrown, both the currency and the insurance are worthless, and galleons suddenly look very stable. There’s also nothing to say that Gringotts is so convinced of their security measures that they guarantee the money of their depositors– and instead of faith in the government, they put their faith in the Gringotts security system.

My larger point about money is that we do not have sufficient historical and economic data to conclude that the way the Wizarding world does this is BECAUSE they are reliant on magic. You assume that the alternatives the Muggle world uses are viable, which they may not be. I think it’s more entertaining to assume their system arose for a variety of good reasons. In Star Trek, cash societies use latinum, not because they are blind to the advantages of paper money or computer credit, but because while objects can be replicated and computers can be hacked, latinum cannot be faked. You have no basis to conclude that they have not chosen the wisest policy other than your assumptions that their world’s economy mirrors ours.

The Wizarding World is still stuck on a gold standard of money in the 20th Century. One can only imagine the Weaseley’s would have a much easier time getting out of poverty if it weren’t for a massive liquidity problem…..

….?

Oh, you children.

You want to know WHY that would be an even bigger disaster, read up on the Weimar Republic and the collapse of the (completely fiat) german mark. The gold standard only has “liquidity problems” for people who desperately want to cheat the system. And its fiat replacement always, invariably, inevitably strikes a point where it collapses because the “magic” of Fiat can no longer cast the illusion that the money printed by the bank is a fake receipt for an imaginary commodity.

Investments, interest rates and the like existed long before fiat money. The fact that Harry’s wealth simply sat in a vault doing nothing is attributable to either his parents being shortsighted, or to the author simply not going into detail about trust funds and investment procedures (we’re here, after all, to watch Harry become a wizard, not an investment banker.)

Great article.

I have a bunch of thoughts on the whole wizard ecnomy/money thing, but I”m going to saty away from that for now (I got into a pretty involved conversation about it in the comments of another article that had very little to do with HP).

I do want tor bring up the idea that Law, through out much of history, was in fact considered and treated exactly like “magic.” The only difference was that it wsn’t called magic but Nature or God. Until the Enlightment, laws were considered to be part of the natural order, or they were handed down by representetives of supernatural (Magical to us non-believers) beings. Some of the first laws were also religious texts or edicts, e.g. the ten commadments. Later, in Europe, the word of te king was considered to be law because he had access to a power no one else had: being a direct representative of God. In fact, it was the same process that began the de-magification of Nature tha began the de-magicalization of law. Until many of the discoveries of the Enlightement, Nature was thought to be controlled by concious supernatural beings or elements whose will is to be interpreted by priests, oracles or other “experts.” By discovering and writing down the forces that goverened Nature, people like Newton made the understanding of nature potentially accessible to everyone. Around the same time (brodly speaking) people like Hobbes were trying to discover the forces that goverened society. Unlike Newton, however, Hobbes doesn’t discover any natural forces that demand the existence of a lawmaking authority. He discovers that it’s the goverened that are consenting to being goverened in order to keep people from constantly screwing each other over. This idea will ultimately sever the lawmaker from his “magical” source of power and bring it to a much more prosaic, material and understanable source: humans. This eventually leads to the proliferation of democratic and constituntional philsphies and movements.

As you point out, however, in HP the laws aren’t created by a person or institution that governs, but by a natural, physically evident set of forces called “magic.” The laws of magic are as unchangable at the laws of physics. Wizards can’t wrest the control of lawmaking from the authorities any more than we can wrest the control of gravity from the mass of objects. Perhaps the immutability of laws means The Age of Reason skipped right past the magical community and that’s why their government, education and banking systems seem so strange; there were no Wizard versions of John Locke, Denis Diderot, or Adam Smith. Finally, if we take this logic to an extreme conclusion, we realize that magic makes any form of constitutional government practically impossible.

This should definitely be part of some podcast/article, with likely involvement of Cognac.

I liked the discussion about substituting law with magic, but I am not entirely sure with part of the conclusion. Wizards don’t merely concern themselves with magic (“and breathing,” to quote a Spongebob episode). For one thing, literature does exist in the Wizarding world, as Tales of Beedle the Bard played a central role in the last book / movie. Oral tradition does exist (I seem to recall some proverbs tossed here and there in the book), and the history of magic matters (especially that which concerns Dumbledore). The humanities matter to wizards too, though they might call it differently (wizardities?)

More generally, I don’t agree that only a specific subset of words matter in Harry Potter. Words are as important for wizards as for muggles. Trickery, coercion, and deceit abound in their world, and non-magical words are very much involved. Expressions of faith, hope, and love are still being done through non-magical words. I even think that the presence of magic makes non-magical words all the more precious: everyone can do magic with enough skill, but not everyone can make a wizard or warlock love or trust someone.

(Of course, it would be a very different thing if wizards can only speak using magical words. On the other hand, given that a human mind needs to think of that story, human elements would still come into play eventually.)

BTW, the way the discussion focused on the fiat currency made me think of this as a possible podcast topic, something like magic and the monetary system. I smell Fenzel involvement here.

While we’re on the subject of magic, I would like to mention the treatment of magic in The Fairly Oddparents. In there, they specifically have a big book of rules (aptly named Da Rules), which ties both magic and law pretty nicely. I also like their focus on the inability to “interfere with or create true love” (however comical it could get), which illustrates the moral compass of the show.

Oh, and their set of rules is very interesting indeed: http://fairlyoddparents.wikia.com/wiki/Da_Rules

Awesome! Was this inspired by that conversation on your last piece that DeanMoriarty is referencing? ;)

I suppose as a supplemental or example to bolster your claim that written law isn’t as powerful as magic: The Unforgivable Curses. Why are they forbidden? Because humans (wizards are never said to be non-human, after all) attempt to impose human-made rules onto them. But one only gets punished for casting a Unforgivable Curse by getting caught doing it by another wizard/witch that reports it to the Ministry of Magic, and, further, the Ministry then has to apprehend the person (and they may or may not have a trial). The spells exist on their own, but the significance of them being “unforgivable” only exists post-hoc in the sense that the law cannot physically prevent them being cast. So someone without any care for Ministry rules could go avada kedavra-ing all they want.

But then I’d like to push something Dimwit said further, but take his point away from currency and back to words and law.

I wonder what the copyright rules are on spells? Hermione is probably going to be the wealthiest of them all since she comes up with new ones all the time which would be where the value lies.

Hermione isn’t the only character we know of that invents spells. Snape also does it, as we learn. And where did the spells come from originally? A witch or wizard somewhere came up with the right words to make the right thing occur. So I think the implications then would depend on your interpretation of what magic “is.” Is magic a force out there that gets manipulated in ways depending on the word(s) used, wand, individual magic ability? Does the ability to do X exist before or after the words are assigned? So, for example, was the spell for fixing glasses, occulous reparo, floating out in the ether, unnamed until a witch/wizard metaphorically stumbled upon it when pissed about some broken frames?

I guess what I’m getting at is the question of whether new spells come about as a result of innovation or discovery. And then if the witch/wizard responsible for making it known should be seen as the progenitor or caretaker.

Bah, sorry to assume you’re a male, Dimwit. I should have said “their” up there.

De nada. You were right.

Also, some other examples I can think of to go with the Unforgivable Curse one are the use of magic in front of muggles or by minors during vacations.

>> And where did the spells come from originally? A witch or wizard somewhere came up with the right words to make the right thing occur. So I think the implications then would depend on your interpretation of what magic “is.” Is magic a force out there that gets manipulated in ways depending on the word(s) used, wand, individual magic ability? Does the ability to do X exist before or after the words are assigned? So, for example, was the spell for fixing glasses, occulous reparo, floating out in the ether, unnamed until a witch/wizard metaphorically stumbled upon it when pissed about some broken frames?<<

It's clear that it's much more difficult than that, otherwise Hogwarts would not exist. You can see in the beginning that pronounciation, intonation, gesture and magic ability are all important. Any one of them is wrong and the spell doesn't work. It would follow that the more powerful and complex the spell, the more likely that the consequences of failure would be higher as well. It would stop idle experimentation. But it would also follow that there are relationships between spells. Snape is a chemist/alchemist. A known scientific bent and logically driven. He would experiment and accrete knowledge. Hermione lives in the library. I can see her creating a codex for spells through previous works. Neither are simply waving their arms about and spouting latinish phrases to make new spells.

Absolutely! I didn’t mean to make it sound like people just stumble across spells randomly. As I said, my question is whether spells are a result of a person, through their experiments, finding the exact right way of casting (motion, words, ingredients if necessary), or if new spells develop because a person manipulates magic itself skillfully enough to then add said spell(s) into the ether. Did that witch/wizard come up with that incantation etc. through trial-and-error, or did they FIND it through it. I guess it’s kind of semantical, but I’m getting at the nature of magic itself. Whether it’s its own thing that some are better at unlocking than others, or if it’s a thing some are better at adding to than others.

I guess I did say “stumbled upon,” but I meant it more in the sense that they were trying lots of things and happened across the right one. Sorry. :(

If spells are added ‘to the ether’, is the use of Latin just convention, or is Latin somehow an innately magical language? If the former, what’s stopping a mischievous wizard or witch from making a spell that is invoked by something simple like ‘hi’ and a handwave? Similarly, If the latter, how did Roman wizards go about their day without accidentally triggering all sorts of spells?

Excellent article! I’m afraid you strayed too close to the gold standard sun there though and brought out… a certain element in the comments. Still, it was a very interesting read.

Ben,

The notion that a legal wand makes a physical bill worthwhile is 100% correct, though I quibble with the specific argument made (as well as some of the comments above):

The value of currency is purely transactional: I give you this piece of linen; you give me “my stuff”, that person can now go get some stuff of their own. This never-ending (unless central banks/ accidents/ protests intercede) series of transactions revolving around a physical object works because anyone in a position to sell “stuff” believes they can go somewhere else and do likewise with the object. A contract of sorts is entered into: “I give you my goods, you provide me means to get goods of my own”. However, when a “contract” is entered into and the physical object involved is not what it appears, then the contract being upheld is at risk. Eventually, somehow, the physical objects is scrutinized and the contract is realized to be crap and the current participants are stuck with the problems (even though the original problem likely occurred well-removed from the 2 participants)

Legal sanctioning of physical items (like a police badge for instance) assures participants in a system that a particular set of characteristics are assigned to the person/thing is an act of declaring that an exchange medium is approved and standardized across all market-participants which creates the level of trust required by all the participants to perpetuate the system. The value of legal sanctioning is not derived from some legally binding agreement that certain pieces of linen are great and others aren’t. The mere presence of the system (and subsequent enforcement) leads to the belief by all participants that the system works and therefore insuring the perpetuation of the system until that belief is shaken (inflation,for instance).

Yeah I clearly made a tactical error by focusing so much on the “money” stuff.

I agree with you about the interpretation of money as “You give my goods, I give you the means to get goods of your own.” That said, I think the distinction between the Muggle and Magical world stands. Wizards still have MONEY – they use as gold as their “means to get goods of your own.” Gold is an arbitrary choice as a medium of exchange – it’s not THAT much more intrinsically valuable than any other useful good, but it’s fungible and rare, so it’s a useful way of capturing value in a physical object.

What I think is important to note is that the Wizarding world doesn’t even have gold-backed paper – they literally carry around pieces of gold. I made the mistake of distinguishing the Wizarding world from our own on the basis of what backs the currency – which isn’t nearly as important as what is actually being used as currency.

Even in gold-backed system, where a bill is really just a certificate that you can exchange for gold, there’s still a “magical effect” going on – if the National Bank issues me a piece of paper that I can redeem for gold, I can’t redeem the copies of the bill that I make at home (or if I do, I’m breaking the law).

The Wizarding world would have trouble with the concept – in a world with actual magic, why would you care about the “magic” of a bank saying “This is a Dollar; that isn’t a Dollar.” The distinction between fiat currency and the gold standard was probably a mistake to include – the real difference is between paper money that has representational value (of whatever providence) and physical gold that has intrinsic value.

Also, “Hey Charlie!!!”