Matthew Belinkie: Can we have a philosophical discussion of “The Gambler?” Lyrics here. Basically, the narrator is on a train “bound for nowhere.” The Gambler tells him that he can see the narrator is “out of aces,” and offers him some advice. (The advice is perhaps slightly suspect because he demands whiskey AND a cigarette before giving it.) Here are the lines that are a direct quote from the character:

If you’re gonna play the game, boy, ya gotta learn to play it right.

You got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em.

Know when to walk away and know when to run.

You never count your money when you’re sittin’ at the table.

There’ll be time enough for countin’ when the dealin’s done.Now ev’ry gambler knows that the secret to survivin’

is knowin’ what to throw away and knowin’ what to keep.

‘Cause ev’ry hand’s a winner and ev’ry hand’s a loser,

and the best that you can hope for is to die in your sleep.

There’s a lot to unpack there, starting with “if you’re gonna play the game, boy.” He’s implying that this isn’t all-purpose life advice. The Gambler somehow knows that this narrator has CHOSEN to “play the game” and that he’s not very good at it. In any case, the narrator seems to appreciate the advice, declaring it to be “an ace that I could keep.”

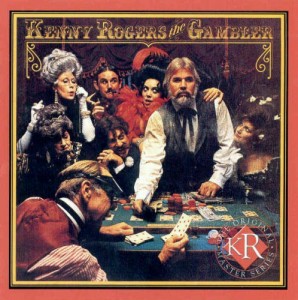

The art direction of this album cover is worthy of a post by itself.

On the one hand, the advice seems very generic. Yes, obviously knowing when to hold ’em and knowing when to fold ’em is a useful skill. The most striking part is the final line: “the best that you can hope for is to die in your sleep.” What exactly does he mean there? That gambling never pays in the long run, no matter what you do? Or that all the riches in the world don’t matter in the face of a painful, agonizing death? Certainly, the mention of death puts the earlier lyric, “there’ll be time enough for countin’ when the dealin’s done,” into stark focus. Perhaps the lesson the narrator learns from the Gambler is not to dwell on either success OR failure, because life goes on in either case. Just focus on the hand in front of you.

Peter Fenzel: I tend to assume “The Gambler” is about a man leaving his wife, probably because of some random thing I heard or read somewhere. It doesn’t have to be, though – but I think setting up the context of a failed marriage is a good way to frame and contextualize the gambler’s advice.

One hint that this direction might be right is that the two people are sitting silently with each other and staring out the window, and the only reason they talk to each other is out of boredom. Also, the train being “bound for nowhere” indicates that the man isn’t traveling toward something, but away from something, but also that he feels aimless and without a future.

But yeah, it doesn’t have to be about leaving a woman, but I assumed it was.

If it is about leaving a woman, then this is what the gambler’s advice says:

I’m good at reading people, and I can tell you’re running from an obligation, that you’re depressed and you feel like you’re out of options.

You need to know when to work through the problems in a relationship and when those problems are not going to be fixable or worth your time. You need to also know when it is time to leave a relationship because it is over, and when to get the hell out of a relationship because it is bad for you.

Don’t sit in a bad relationship thinking about your responsibilities and promises, or how people will judge you if you leave. Everybody is judged when they die. No need to judge yourself now.

At the end of the day, this is your life, and it is shaped by your actions, not your circumstances, and nobody can tell you how to make your choices. Trust your instincts and do do what you feel like you need to do while you’re alive. There’s no special reward upon your death for being a good person, other than peace of mind.

I think “the game” he is playing is the game of trying to live life the way he wants to live it rather than following his apportioned social role – that is, if you’re going to take drastic action like leaving your wife and getting on a train for parts unknown, you should consider that dwelling on the implications of your choices isn’t going to help you.

Kenny Rogers was only 40 when “The Gambler” was released, but Just For Men had not yet been invented. (NOTE: Yes, I actually checked when Just For Men was invented. It was 1987.)

If you step away from it being about a woman and consider it more generically, I think it is definitely about looking to yourself as the arbiter of your choices, while at the same time recognizing the effects things are having on you – that you are ultimately the person who decides what is worthwhile, but that if your gut is telling you something isn’t worthwhile, then you should own up to that and distance yourself from it.

It’s about not letting your conscious volition’s insistence on external ideas of right and wrong or your mind’s insistence that it can bear all things to prevent you from listening to your instincts, your heart, and your better judgement about what you actually want to do.

And it’s also about recognizing the extent and scope of your life – as well as its limits. That this freedom to follow your instincts comes with a realization that both there isn’t a Sword of Damocles hanging over your head (yay!) or anybody waiting to pat you on the back for a job well done when you die (boo).

I assume the gambler is a poker player, which seems reasonable, since he talks about people hiding how many aces they have. In poker, the externalities of the game are random – the deck doesn’t care whether you win or lose, and it is ambivalent toward the cards it deals you.

I assume the gambler is a poker player, which seems reasonable, since he talks about people hiding how many aces they have. In poker, the externalities of the game are random – the deck doesn’t care whether you win or lose, and it is ambivalent toward the cards it deals you.

But just because your cards are random and you can’t control them, that doesn’t mean you have no control of the game once the cards are dealt. Taking that control comes with advantages and disadvantages, freedoms and restrictions – but the gambler seems to think it is necessary for coping with the way the externalities of life work – and the Kenny Rogers character finds strength and a coping mechanism in it that gives him a renewed sense of direction (his “aces,” which along with being good cards, also tend to guide you in poker toward putting your money out on the table).

Jordan Stokes: I remember reading somewhere, at some time, that the thing that separates a good poker player from a bad one isn’t their ability to get good cards, but what they do with the cards that aren’t good. Successful players will not bet on a bad hand. I mean, they’ll bluff on occasion, but they fold after the initial deal MUCH more often than than a bad player, who will get emotionally invested in the progress of the individual hand and keep trying to draw that inside straight, or whatever. In this sense, the fact that the gambler’s advice is mostly about when to get out of a situation is just good practical advice for a beginning gambler.

The bit about not counting your money illustrates another important point, which is that the odds in gambling are stochastic: nobody’s ever “due” for a big win. Your odds of drawing good cards in this particular hand are the same if you’ve been winning all night as they are if you’re on the world’s worst losing streak. As a result, how much money you have or don’t have should never really influence your bet — not once you’ve committed yourself to playing. (Deciding whether you can afford to play, or whether you can afford to keep playing, or whether you should quit while you’re ahead, is something else again, and probably falls under the category of “when the dealing’s done.”)

Now, I tend to agree that the titular gambler is not really talking about cards (although I don’t see any reason to suppose that he’s talking about romance in particular). So consider these lessons as general life advice: first, be prepared to abandon a lot of things that most people would tend to cling to. The specific form that this takes in gambling (i.e. bail at the first sign of trouble) is probably less important than the underlying injunction to value the valuable and shun the valueless… and the implication that telling the difference between the two is not always easy. Second, taking the right action in any given context is more important than the outcome of those actions in the long term. Which is a crazy thing to say (in that theories of value are almost always utilitarian, deep down), but on the other hand kind of a cliché: you can’t take it with you, life’s about the journey, etc. etc. etc.

Peter Fenzel: One of the contradictions in what I said earlier is around “judgement.” The gambler talks both about counting his money when the game is done and also about how the best thing he can hope for is dying in his sleep.

The best time to count your money is when a ghost gives you a glimpse of the outcome of the game. But this is a violation of standard tournament poker rules.

Well, can’t he count his money when he’s dying or dead – look back on his life and determine whether he came out ahead?

According to the song, apparently not. Or, at the very least, he’ll find “breaking even” was the best he could do.

This might mean that the “money” in the game of poker of life actually doesn’t matter – that the “money” in life, which could also be virtue, happiness, kept promises, any of that, is a McGuffin – that really any satisfaction you get comes from playing the game well and in accordance with, again, your instincts, your gut, and your better judgement.

It could also mean everyone will be judged, and it will be bad – that your chips will be counted, but don’t stress about the chips, because the final count will definitely not be in your favor. That you can and will spend the time after you’re dead bemoaning all your shortcomings in life, so no need to dwell on it now.

Also, “counting your money” could be equated with “judgment” in terms of how sometimes judgment just means everybody dies, without an eye toward good or bad or any unearthly reward. Judgment Day will break all bonds, cast the high low, etc. – meaning that the ultimate judgement is we are all equally condemned to die, regardless of our virtue.

But yeah, it’s a contradiction in the song that is I think pretty deep in the fiber of country music and American folk literature – that we’ll all be judged, but that when it happens, it won’t matter what we did, one way or another.

Matthew Belinkie: I think it’s important to remember that we only know two things about the Gambler character:

1. He is a professional gambler

2. He cannot afford his own whiskey and cigarettes

Would you take gambling advice from this man?

Is it possible that he simply got on the train without whiskey and cigarettes, and that he has a whole ROOM full of them back at his mansion? Sure, but I’d say the songwriter is implying that this Gambler is hard on his luck, worse off than the protagonist, who is not doing so well either.

Now on the one hand, why should we trust a broke gambler? This guy can’t possibly have anything to teach us. But it’s precisely BECAUSE the man is broke that his advice means something. The song is more about loss than it is about winning. (I really love the line “Know when to walk away… know when to run.” There’s a little joke there, since you expect the second half of that to be the OPPOSITE of “walk away,” a la “hold ’em/fold ’em.” But I think the writer is also telling us that you’ll be folding MORE than holding, in cards and in life. You should play very cautiously.)

I think the gambler isn’t so much telling us how to win at life, but how to bear loss gracefully. One must have the humility to run, and the zen not to dwell on how our chips have dwindled to a pitiful little stack. I see two guys in a train car, the narrator who thinks he’s got it bad, and the gambler who has it even worse. The narrator is depressed, but the gambler is not. The gambler is telling him how to let go of that worry.

By the way, for some reason, Phish covered “The Gambler” at a live show this summer… with Kenny Rogers singing:

For some reason, they didn’t make it last 25 minutes.

Peter Fenzel: One of the cool things about the “know when to run” line is that the most archetypical reasons for a country gambler to run are:

1. He cheated in the game.

2. He won a lot legitimately, and the other players are after him to get their money back.

When to run.

There’s a poetry to that – that sometimes you run because you did everything wrong – and sometimes you run because you did everything right.

It’s a cool contrast to “walking away” – which you sometimes do because you’ve done a little well or a little poorly. And it reinforces that the gambler’s philosophy is somewhat disconcerned with whether the reasons you’re doing something are good or bad reasons. The Gambler is definitely against guilt.

Yeah, he’s a poor gambler, but he’s an old gambler, and that’s the main reason to listen to him – because he’s stayed in the game for this long. He doesn’t promise the secret to prosperity – just the secret to survival.

It’s characteristic of gamblers in this tradition that they avoid commitments and attachments, and prefer freedom to stability. So, yeah, if your preferences run the other way, you’re not “playing the game,” and the Gambler’s advice won’t interest you.

I definitely agree that the advice is primarily about psychological health, well-being and what can be gotten in the direction of happiness – and that coping with loss is a huge part of it.

Matthew Belinkie: Here’s another angle. The gambler is described as “too tired to sleep.” But after he passes along his advice, he does. He even puts out the cigarette that he bummed off the narrator. Perhaps the advice was a huge weight on him that he had to unburden himself of before he could die. Or perhaps passing along the advice gave him a tremendous source of satisfaction that allowed him to die at peace. In any case, it’s interesting to consider the gambler’s frame of mind. Does he know death is coming? Does he know this might be the last conversation he’ll ever have? Certainly, the line about “the best you can hope for is to die in your sleep” is a little different if the gambler actually thinks that’s about to happen. I wonder if, despite what the narrator says, the gambler is really “too tired to sleep” at the beginning of the song, or whether he’s afraid to sleep. Maybe the song is really about an old man making a deathbed confession.

Peter Fenzel: Yeah, one way the old gambler might “break even” is by paying off an unpaid debt.

Maybe the old gambler feels like he didn’t help people enough in his life, and when he helps Kenny Rogers, it balances an account for him and he gets to go – sort of like a ghost tied to Earth by unfinished business.

Maybe it’s owning up to the way he’s lived his life, or owning up to his own guilt and fear of death, acknowledging what he really hopes for.

Maybe it’s the connection with another human being.

The “somewhere in the darkness, the gambler, he broke even” sounds a lot to me like when Zuzu rings the bell on the Christmas tree in It’s a Wonderful Life and George Bailey knows that, somewhere, Clarence just got his wings.

By which I mean Kenny Rogers speaks like he has supernatural, revelatory knowledge that the gambler sharing this advice with him was a Good Thing, and that he was rewarded for it.

Matthew Belinkie: The “paying off the unpaid debt” interpretation seems backed up by Rogers’s appearance on The Muppet Show. In this version of the song, the gambler’s ghost comes out of his body and does a giddy tapdance.

Peter Fenzel: Although if we go with the Wyclef Jean / Kenny Rogers / Pharoahe Monch remix, then the meaning of the song is “make sure to prepare adequately for hip hop performances and DJ gigs.”

Jordan Stokes: Whenever we try to understand the meaning of a song, it’s important to compare it to its Wyclef Jean remix, because ‘Clef can usually be counted on to totally miss the point in a way that’s both interesting and revealing. The Wyclef version of “The Gambler” is obsessed with personal identity. Kenny Rogers introduces himself by name, then Pharoahe Monch delivers a guest verse that begins by quoting pretty much the whole hook from his signature song “Simon Says.” And then Wyclef’s verse is like “Kenny Rogers and Pharoahe Monch? No way, this can’t be.” The whole point of the song is that it’s these particular guys doing it; it’s relevant to us only in so far as we already give a damn about them and their concerns. While both songs are supposed to impart life lessons of a certain sort, the Wyclef version suggests that merit is something that can best be acquired by being Kenny Rogers, Wyclef Jean, or Pharoahe Monch — or failing that, by spending as much time with them as possible in hopes that some of it will rub off. “My destiny is to lead, and y’all follow./ This is Showtime, and I’m Live at the Apollo.”

In that “The Gambler” is as much Kenny Rogers’ signature tune as “Simon Says” is Pharoahe Monch’s, it has become a song where the singer’s personal identity is very important. But looking at the two side by side, I’m struck by the degree to which The Gambler is a universalized parable. None of the people involved are specific — the Gambler is just the gambler, and the Kenny Rogers “I” persona is a stand in for all of us. (Imagine how altered the song would be if it lead off with “On a warm summer’s evenin’/ on a train bound for nowhere,/ I met up with a gambler,/ and his name was Chet.”) So I don’t think the fact that the gambler is broke, or that he’s old, really matters. The advice is supposed to be good advice because it’s good advice, no matter who’s giving it. This also lines up nicely with the idea that living your life the right way, while important, has no real bearing on where you end up at the end of the day. (Death, when you think about it, may be the last truly democratic institution we have left.)

I always thought of “You never count your money when you’re sittin’ at the table” as meaning “Don’t antagonize your opponents by flaunting your winnings in their faces” (dovetailing with “know when to run” as interpreted by Fenzel). “Don’t tastelessly flaunt your success” is reasonable general life advice, too.

‘the best you can hope for, is to die in your sleep’. As a gambler myself, i think he is implying that it’s a tough living and dying is the easy way out.

For me it’s the second part that hits home:

Know what to get rid of that weighs you down and sucks the energy out of you (ie: toxic people, relationships, guilt, emotional baggage), and know what to value in your life (ie; good people and relationships).

You can only play the cards you’re dealt; it’s all up to you to make it a good life or a crappy one.