By now, surely you’ve seen the viral music video sensation “Gangnam Style” by Korean singer PSY. If not, do yourself a favor and watch it now:

And if you’re a fan of pop culture analysis, you’ve probably also read one of the many articles that offer interpretations of the meaning of the song and the video. Long story short, it’s a clever critique of South Korea’s culture of conspicuous consumption and growing economic inequality.

Show of hands: how many of you got that, just from watching the video? You, with your hands up. You’re either Korean or have lived in Korea long enough to reach a high level of linguistic and culture fluency. Put your hands down. For the rest of us, the Overthinkers included, the meaning or message of this song is totally lost upon us without outside explanation.

This is not a horse from the video. This is @horse_ebooks.

We made a concerted attempt to decipher the video, starting with the visual aspects that aren’t dependent on understanding the lyrics. But even with the help of translated lyrics, our interpretations were incomplete at best and laughably off base at worst. (Using my thin-but-nonexistent knowledge of Korean culture, I wrote several paragraphs analyzing the symbology of the horses through the lens of Chinese astrology. I was mostly talking out of my ass just to be clever, but I thought it had a fighting chance of being accurate. It turns out I was just talking out of my ass.) In other words, we were all missing the point of the video, and we would have continued to have missed the point were it not for those articles that explained the meaning for us.

Here at Overthinking It, we’re no strangers to episodes of pop culture misinterpretation. We’ve traced the source of Ronald Reagan’s misappropriation of “Born in the USA,” we’ve taken down Fox News’s allegation of communist ideology in The Muppets (with a Marxist interpretation of The Muppets, ‘natch), and we’ve written thousands upon thousands of words about how critics and audiences repeatedly fail to appreciate the critique of fascism in Starship Troopers.

Not communist. Marxist.

When thinking about our failure to fully understand “Gangnam Style,” I considered it in the context of these examples. We missed the point, but not in the same way that Fox News missed the point when it saw a nefarious communist subtext in The Muppets. The meaning of “Gangnam Style” is nearly impossible for a non-Korean to get, whereas the meaning of The Muppets should be obvious to anyone who isn’t trapped in a nightmarish right-wing propaganda machine. The consequences of us not getting “Gangnam Style” aren’t particularly severe. Sure, we’re missing out on some interesting social criticism, but it’s targeted at a different cultural context, and our not getting it is not some indicator of lack of intelligence or sensitivity on our part. The consequences of misinterpreting The Muppets, however are more severe. Someone who actually believes that The Muppets is a liberal conspiracy to brainwash children is missing out on the positive themes of an entertaining movie and, more importantly, exhibits the lack of sound reasoning that goes along with being trapped in a nightmarish right-wing propaganda machine.

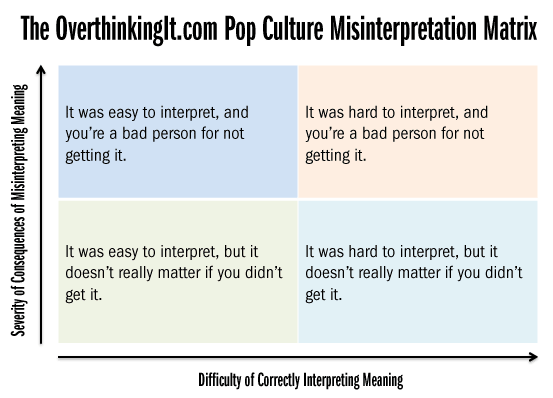

In other words, there are two variables at play when it comes to the misinterpretation of pop culture:

- How easy or difficult it is to correctly interpret the meaning

- How severe the consequences are of misinterpreting the meaning

(Note: for the sake of this post, we’re going to bracket any discussion of what it means to “correctly” “interpret” the “meaning” of a piece of pop culture. I of course acknowledge the inherent subjectivity of any such exercise. That being said, feel free to duke it out on the comments.)

Using these two variables, let’s create a handy two-by-two matrix to illustrate four archetypical scenarios for misinterpretation of pop culture:

(I swear, I have not been to business school. I just happen to think that the two-by-two matrix is a convenient way of visualizing scenarios controlled by two variables. Which it is.)

Let’s start with the top left hand corner and work counterclockwise through the different quadrants.

Greed. Is. Not. Good

1. It was easy to interpret, and you’re a bad person for not getting it.

This is far and away the worst way to misinterpret pop culture. The Fox News example of communist brainwashing in The Muppets fits into this quadrant, but the best example of this type of misunderstanding is Wall Street and Gordon Gekko’s “Greed is Good” ethos. Michael Douglas complains that he receives misguided praise from financial professionals who see his Gordon Gekko character as a hero and “greed is good” as words to live by. Misinterpretations in this quadrant reflect poorly on the judgment and value of the misinterpreter.

We. Are. Not. As. Young. As. We. Used. To. Be.

2. It was easy to interpret, but it doesn’t really matter if you didn’t get it.

When I say “doesn’t really matter,” I mean that I won’t think you’re a bad and/or stupid person for missing the point. Examples for this quadrant aren’t nearly as easy to think of compared to the first quadrant, but I think there’s one to be had with The Expendables and its sequel. If the movies are “about” anything, they’re about older men struggling to remaining relevant beyond their primes. This theme isn’t buried under layers of subtext, and it should be fairly evident to anyone with even a passing knowledge of the careers of the movies’ stars. But I’m sure it was lost on plenty of people who walked away from that movie thinking “EXPLOSIONS STALLONE SCHWARZENEGGER WILLIS YEEEEEAAAAAHHH!!!!” and little else. But that’s not any sort of character indictment in the way that watching Wall Street and thinking that greed is good is an indicator of poor judgment and lack of values.

Vegetarians are annoying?

3. It was hard to interpret, but it doesn’t really matter if you didn’t get it.

Our misreading of “Gangnam Style” isn’t the best example for this quadrant, due to the enormous language and culture barriers that stood in the way of any non-Korean’s full understanding of the music video’s message. A better example is actually Troll 2. The creators of this screamingly bad horror movie have claimed that this movie was meant to be a criticism of vegetarianism, but you’d be forgiven for failing to pick up on this amidst the cringe-worthy acting and nonsensical storyline.

?

4. It was hard to interpret, and you’re a bad person for not getting it.

This, my dear readers, is where you come in. I can’t come up with any examples that belong in this quadrant. Can you? Is there a piece of pop culture that’s difficult to “get,” and if you don’t “get it,” then that reflects poorly on your judgment or character?

It’s possible that no scenario for misinterpreting pop culture can fit in this quadrant, or that my two-by-two matrix is insufficient in capturing the nature of this phenomenon. Or that I’ve created the world’s first two-by-two matrix model with only three quadrants. Which isn’t likely, since I’m pretty sure you have to go to business school to learn how to do that. But I digress. If you have any thoughts on how to fill the 4th quadrant or if my quadrants reflect poorly on my judgment and values, let me know in the comments.

As an example of “hard, but important, to interpret” I’d go with basic, archtype-level traditions and mythologies from a culture that is not one’s own. I know that’s not exactly “pop culture” (it pretty much is a non-overlapping set), but by virtue of the fact that these stories are important or significant to (and not merely “popular in”) the culture from which they come is precisely what makes them important to understand.

My nominees for the fourth quadrant are pieces that are theoretically critical of their subjects, but portray them with such empathy and/or glamour that it’s easy to read them as uncritical.

Whether this is a failure on the part of the audience or incoherence on the part of the text is left as an exercise to the art philosophers.

Prime example: Fight Club. I think the movie is, in the end, a rejection of Durden-ism. Confronted with the destructive consequences of unleashing his violent, nihilistic movement, the narrator puts a gun to his own head to kill the part of him that thought it was a good idea.

On the other hand, Durden is played by Brad Pitt. And before he plots the bombing of skyscrapers, he starts out by delivering a hugely resonant critique of consumerism and the confusion left in the wake of the decline of traditional masculinity.

And the end result is college kids with the rules of Fight Club on a poster.

Similarly, there are piles of war movies that are textually delivering a “war is hell” kind of message but can be read as straightforward action/heroism narratives where war is just providing the justification. Depending on the coherence of the movie in question, this could slide from the first quadrant (cheering at “Apocalypse Now”, for instance) into the fourth.

I personally have a whole category of movies that I’m not sure if they’re fourth quadrant or not– 300 and The Boondock Saints are the leaders. If the thematic question is “Isn’t this awesome?”, they’re kind of problematic. If the thematic question is “Isn’t it a little sick that we think this is awesome?”, they’re pretty great.

I will agree with you on that one. Fight Club, on its surface, seems to be a critique of consumer culture, which is then turned into a revenge fantasy on the corporate world perpetrating that consumer culture. But underneath all of that is the message that revolutionary movements never really work. The lessons Durden tries to impart to his compatriots end up getting turned into chanted mottos. He tells them, “Do what you want! Think for yourself!” and they all chant back in unison, “Think for yourself!”

If there is any reason why I don’t think it quite fits into the fourth quadrant, it is that the movie changed the ending of the book. At the end of the book, the bombs don’t go off, and after Jack shoots himself, he wakes up in a hospital, and he thinks that he’s in heaven. At the end of the movie, though, he stands with his arm around Helena Bonham Carter as they watch skyscrapers crumble into dust, and the Pixies start playing. The most obvious reaction to an ending like that is “FUCK YEAH!”

I definitely get what you mean about 300 and Boondock Saints. I feel like the latter is easier to enjoy, because even though the only female characters (that I can remember) are hookers and strippers, there was some sense that what the guys were doing was justifiable. To borrow from TVTropes, the uncomortableness of it is more of a “fridge moment”–right when it’s over, the movie feels like it was awesome, but then later you’re thinking about it and realize, “Huh, that was actually kind of… messed up.”

In the case of 300, well… they took a text that was already misogynistic and hypermasculine, and decided that it needed an extra rape scene. And ninjas. (I don’t remember ninjas being in the graphic novel, but maybe it’s been a while.) The result was so ridiculous that it seemed like a parody, but I knew that it was not possible to read it as such. These dudes were serious.

That ambiguity is actually exactly why I think Fight Club is 4th quadrant. If it were clearer in its rejection of Durden-ism, it would be 1st quadrant.

Fincher is really good at this, actually. The Social Network pulls a similar trick. If you just read the script, Social Network would seem like a straightforward, almost didactic tale about the alienating effects of ambition. Fincher’s direction is, I think, more sympathetic to Zuckerberg’s character than the script is, and finds some glamour and empathy in him that ends up elevating the movie while also making it less morally clear. Very similar to what happens to Durden.

I think our readings of the artists’ intentions in Boondock Saints and 300 are pretty well aligned. Fortunately, I don’t believe in the primacy– or even relevance– of artistic intention, and I like them both better with my contrarian, ironic readings, so I’m sticking with them.

Absolutely agree with “pieces that are theoretically critical of their subjects, but portray them with such empathy and/or glamour that it’s easy to read them as uncritical.” as the 4th quadrant, though the first thing that popped up in my mind was Lolita (the book and perhaps the SK movie), which is a little less difficult to interpret. In fact, I’m not absolutely sure this doesn’t fall into the first category.

I have met people who think HH is can be forgiven for being a paedo because Lolita seduced him or because he “loved” her or whatnot, and I would put them in the first category of not hard to interpret (paedophilia is terrible and ruins the life of a child); reader did not interpret correctly; this reflects badly on the reader. On the other hand, those who didn’t pick up on Nabokov’s parody and humour and think HH is a horrid man, but that Lolita the book supports his position, which means the book is horrid filth and should be scorned. It certainly doesn’t help that HH as a narrator is intelligent, witty, and has a way with words that helps elicit sympathy.

I think 300 is a great example of multiple levels of misinterpretation that ultimately falls victim in the same way that The Expendables does, but then because of the misconception, causes people to be “bad” people. So it’s more like Quadrant 1. Because in the end, I think the YAY SWORDS thing is what a lot of people take out of it (book or movie), but the critiques of misogyny and imperialism (among other things) get missed and ignored by the audience (readers and viewers alike, and, as you said, hyped up in a way that is just really hard to take as overexaggerated as critique or satire. I honestly don’t think Frank Miller wrote it as a pro-war/masculinity/etc. thing- that’s not his modus operandi at all. I tend to think his original intent was to critique the stuff that gets enthusiastically exaggerated by the movie-makers and ra-ra-ra’d by the fans.

I don’t know about Miller at the time, but recently he actually has been really pro-war pro-masculinity, writing angry blog posts questioning the masculinity of war protesters and the Occupy Movement.

Hrm, so that makes me wonder, does the artist’s own interpretation of the piece evolve? Like it means X to them during the inception phase, but then Y decades later? And is one more legitimate than the other????

I’ll play the ugly American otaku and suggest that Neon Genesis Evangelion is difficult for most non-Japanese anime fans to interpret and failing to to do so makes one a horrible human being. (I truly believed this when I was younger, maybe a week ago.)

It’s a pretty thorough deconstruction of the well-worn “super robot” genre. The creators’ flimsy handling of Christian symbolism distracted some viewers I know personally from paying attention to the important stuff: giant robots are awesome, watch them kill things, children are monsters. Anyone who comes away from that show as a statement on Man’s relationship to God instead of, “Go Nagai wasn’t as deep as I thought he was,” is obviously a bad apple.

I might back you up on this, as I thought Evangelion was supposed to be an allegory for the history of religion (not Christianity specifically). It would be about how sequential, episodic, pointless, and recurringly self-destructive the things we’ve found sacred have been over time.

But obviously I probably missed the boat on this one.

I’m putting away my ham-fisted irony to say that you present a very interesting way of interpreting the show. It seems to me you might think Evangelion is one of those ultimately pointless things that people treat as sacred. I don’t disagree with that.

Right after I re-watched the NGE series, I came away with some kind of interpretation of it that made sense of everything. I didn’t write it down, though–but I’d really like to give it another go. Part of the problem I had was that, in the span of one week, I watched “End of Evangelion,” the series finale for “Puella Magi Madoka Magica” (which I think all anime fans should watch) and the series finale for “Superjail!” All of them are both mind-blowing and confusing.

The way that I interpreted its deconstruction of the giant robot genre was, “You want a series where 14 year olds pilot giant killing machines? Okay. I’ll show you what that would really look like. Because, really, have you even *met* someone 14 years old?”

You’ve made me realize that this break-down of “misinterpretation versus consequence of interpretation” doesn’t account for the possibility of an incorrect interpretation being more positive than correct interpretation. A certain character dies in Madoka and the scene is supposed to be horrifying. The whole anime-viewing internet, however, treats it as comedy. Tons of Madoka fans have produced artwork depicting the scene that are flipping hilarious and enrich everyone’s lives.

It’s a mistake to say that Evangelion isn’t about religion. It just isn’t about WESTERN religion. The rightly called “flimsy” Christian symbolism floats atop a very Buddhist story.

…plus all that other stuff about pedophilia, incest, suicide and robots. :)

Also, I might have to stand up for the ease of interpretation of Gagnam Style. I mean, no, I didn’t get the social satire on first listen, but that’s because *I don’t speak Korean*. Les Miserables would be pretty impenetrable in the original if you didn’t speak French. If you gave me a translation and a quick background on the cultural significance of the Gagnam region, things snap into place pretty fast.

The visuals match up up with the message: The humor is derived from Psy’s exaggerated swagger contrasted against placid bourgeois backdrops. He doesn’t belong there, but he’s trying to act like he does by puffing himself up and strutting, and it’s not coming off as well as his character thinks it is.

If it’s difficult to interpret, it’s because Western music videos have pushed the celebration of consumerist hedonism and conspicuous consumption past the point of parody. Contrast, f’r instance, “Like A G6”, which is “Gagnam Style” without the irony– a list of stuff the speaker’s character can afford, accompanied by awkward dancing. Psy brings his own ironic distance through his calculatedly exaggerated swagger; the viewer has to bring their own taste for the ridiculous to make the Far East Movement funny.

It seems to me that there’s going to be a tendency for any potential candidates for quadrant four to slide into one of the other quadrants. If I manage to interpret something all by my lonesome, I’m less likely to count it as hard to understand in the first place (Fight Club being a good example, actually). And if the interpretation needs to be explained to me, I suspect that it’s either going to seem inherently unimportant, or else, well, trite (‘Hey, kids, Nazi’s are bad!).

That’s not to say I think there won’t be anything in quadrant four at all.

I’d like to throw in Scarface (1983) as another prime example for the first quadrant, I remember countless wannabe gangsters in high school idolizing Tony and his world-view.

I’ve always suspected that The Matrix belongs in the 4th quadrant. It’s pretty much a glorification of terrorists, right? Or at least it takes a group of people who, to the perspective of any normal person, are terrorists, and creates a framework for their actions that make it okay. The climatic action sequence is an assault on a federal building in which a lot of innocent people are killed.

Don’t get me wrong, I love The Matrix. But I sort of suspect we shouldn’t be so comfortable with what the protagonists are doing.

That comes down to what are Terrorists? Depends on who’s telling the story. It’s a loaded word that is very useful for propaganda purposes but poor for descriptive purposes.

Actually, I think “terrorists” has a pretty clear meaning. According to the UN, terrorism is “Criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the general public.”

And now that I think about it, the guys in the Matrix don’t actually meet that definition. They AREN’T trying to terrorize anybody or make a statement. But to the people inside The Matrix (except for the Agents) their actions are indistinguishable from terrorism.

Perhaps what you’re alluding to is that sometimes politicians or the media will be hesitate to label “homegrown” terrorists as terrorists. In the public imagination, terrorists are scary foreigners. I have no such hesitation: if you are committing a crime to terrorize people, you are a terrorist.

Despite this, I think there’s a good OTI discussion to be had (perhaps a future post) about The Matrix.

On the quandrant:

I think that that box is badly labelled. In our culture the whole mythos is that good/bad are easily indentified and you are a bad person for making the wrong choice. If interpretation is hard then you can’t be bad for not getting it, it’s the originators fault for not being clear.

I think a good candidate for quadrant four, depending on how you look at it, would be “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”, by Ursula K. LeGuin. Read it if you haven’t–it’s short, but very powerful. I believe LeGuin meant it to be a paean to those who have the moral courage to walk away, but it’s not clear to me that they’re actually making the right choice in that scenario. And getting this one wrong could conceivably make you a bad person (or at least provoke serious disagreement).

I’m not sure that’s fourth quadrant. For it to be fourth quadrant, the the theme of The Matrix would have to be an undercutting of the protagonists’ actions: “Violence may seem justified but isn’t really.” I don’t think the text supports that reading. The text of The Matrix seems, at least to me, to view the protagonists’ actions as justified.

And the reason for that, as you point out, is that it goes to elaborate lengths to justify those actions. And, within the fiction, it works. The argument that “If you ignore the in-fiction justifications, the protagonists’ actions are not admirable” applies to, well, lots and lots of texts. That interpretive scheme would turn Star Wars into a paean for religious terrorism against large civil infrastructure projects and Die Hard into a story about police brutality against European tourists.

It’s possible for a piece to have clear, easy-to-interpret themes and be wrong and/or problematic, which might be closer to what you are arguing. (And would require the addition of a new, controversial, orthogonal “correct/incorrect” axis to the chart.)

I’m honestly not convinced the violence IS justified. Think about how many people Neo and Trinity kill to save Morpheus. Twenty? A hundred? They blow up that building pretty good. Perhaps the characters believe that Morpheus is valuable enough to justify this violence. (They don’t really make this case, though. Neo just wants to save Morpheus because he likes Morpheus, not because the fate of the world depends on it.) But I think the movie’s REAL attitude is that anyone who is still trapped in The Matrix is sort of sub-human. They don’t know the truth, because they’re not enlightened enough to know the truth, so it’s not a big deal if they get caught in the crossfire. And THAT, I think, is the sort of mindset that leads to terrorism.

I think that the justification in the movie is tied to the idea that any of the people still “plugged in” to the Matrix can be taken over by agents, and can be treated as enemies. But I agree with Belinkie – that’s exactly the sort of thinking that most terrorists use to justify their crime, and the Matrix doesn’t really go very far in asserting the argument, other than the fact that we’re rooting for the humans to win, so we’re more OK with them using extreme measures to do so.

I disagree that the “ignore in-fiction” justifications argument would condemn either Star Wars or Die Hard. In Star Wars, the Empire is objectively terrible – they’re willing to kill a billion people just to interrogate one prisoner. In Die Hard, while you can argue back and forth about McClane’s tactics, it’s not hard to justify the general practice of “Use violence to stop terrorists from taking over/blowing up a building.”

The Matrix is a much tougher nut to crack, and requires you being OK with a high degree of collateral human damage in the fight against the machines (which you might be OK with, but Morpheus’ “they’re still plugged in” argument doesn’t really hold water).

I don’t want to completely threadjack Mark’s post, but this is really interesting. I remember watching the opening scene of the movie, where Trinity brutally beats up the cops that come to get her. “No lieutenant, your men are already dead.” Let’s assume they really ARE dead. How does Trinity feel about that? And how are we supposed to feel about HER? She just killed four cops. Is that really our hero? And step back a little: what is the resistance’s goal? To shut down the Matrix totally? Are we SURE that’s a good idea? Is that REALLY going to improve the quality of life for the seven billion people in there? These guys hate the machines so much that maybe they’ve lost sight of what is best for the PEOPLE.

This is, in part, response to the first part about The Matrix.

I think there is a lot to be said about the power of labels and the cultural baggage they carry around versus the technical “definitions” they are supposedly representing. There is huge debate over whether to call James Holmes (the shooter at TDKR) a terrorist, even though his actions clearly fit that UN definition. What one person may call “revolutionary,” another may call “terrorist.” Terrorism may be defined one way, but it’s socially constructed as something quite (although not entirely) different (I’d say more derivative). What constitutes an “act of terror,” anyway? Is there a threshold over which the body count must rise? Is there a minimum amount of property damage? Where is the line that constitutes it being a public act located?

I haven’t seen the movie in a few years, but I believe there’s a throwaway line about how once a person has been taken over by an Agent, they’re no longer human in the real world; and of course, yes, it gets said that anyone can turn into an Agent in an instant. This, no doubt, is plot device to excuse the huge body count and desensitize the audience to the fact that there are innocent people being gunned down. The huge battle where Neo barrels through like a hundred Agent Smiths isn’t thought of as Neo killing a bunch of PEOPLE.

Actually, I think Lee linked to a 4th quadrant movie right in the article, when you mentioned that a lot of people fail to grasp the critique of fascism that is Starship Troopers. It’s an easy enough message to miss, as evidenced by the fact so many people do. But thinking “fascism is good” is a pretty bad message to take away from the movie is you get it wrong.

I don’t really think this is true, but the most obvious example that popped into my head of a 4th Quadrant object was the Bible, although any other complex holy book would do. I wouldn’t say that this lines up with my personal ethics very well, but it’s probably a good description of many other people’s.

This was my first thought as well.

At least from the Christian standpoint, understanding the Bible is both a) difficult and b) of utmost moral importance. Ditto for the Quran and Muslims, Torah and Jews, etc. etc.

Unrelated Request: Overthinkingit should produce an in-depth chapter by chapter analysis of House of Leaves, designed for those who’ve already read the book.

That sounds like an admirable goal. I’ll solicit interest in a sequel to The Key To All Mythologies on the forums as soon as the forums are fixed.

I think the problem with the fourth quadrant is its framing. “It was hard to interpret, and you’re a bad person for not getting it” focuses only on the negative angle, but how would we describe the people who *do* get it? An alternative way of framing it is to remove the two negatives: “It was hard to interpret, and you’re a *good* person for *getting* it.”

Are there any movies out there that are genuinely hard to interpret, and we assign more status and prestige to those who can sort them out than those who can’t? Of course. The fourth quadrant is art films.

I would say an example of pop culture in the 4th quadrant is the Insane Clown Posse.

The music is fast and angry and confusing, and the whole arc of the Dark Carnival is albums and years long and tremendously complicated. The message of the music is ultimately redemptive and supportive of love and community, but almost nobody without a whole ton of glossing and help is going to figure that out. Then on top of the idea of love and community are layers and layers of abuse, hatred, fear, violence and trauma, which are really difficult to unpack — and I think judging from what I’ve seen, you really have to be part of the group to intuitively understand it — because the truths in it are really culturally uncomfortable.

However, if you listen to the Insane Clown Posse and your response is “those are terrible violent people” — which is I think an easy misinterpretation to arrive at, especially with contemporary bourgeoise prejudices — you are an ASSHOLE. These are people who are already for the most part ostracized outsiders, they are just as harmless as any other large group of young and not-as-young people, and they are very conscious of being scapegoated, mocked and victimized.

There is just no need to go down that road. No good will come of it. You won’t be correct, and all you’ll do is bash a whole lot of people who don’t need to be bashed.

Perhaps this is a pattern that might be seen in more 4th-quadrant properties — socially, you are better off just ignoring this art than trying to interpret it, because your reaction is much more likely to be harmful to yourself and people around you — and to be misinformed — than to render a benefit.

I was reminded by this post of a juggalo-themed Law & Order episode, where a superficial examination of this community clearly concludes “those are terrible violent people”. Basically the police part revolves around catching the deranged, Insane Clown posse-inspired, family massacring and his impressionable young female accomplice, who has been misled by this unquestionably terrible person. My memory of the episode isn’t perfect, but I can’t remember any attempt in the prosecution (the expostion-rich portion of the show) of the killer for any defence of Juggalo culture. It wouldn’t even be too hard, the killer could have tried to present a partial defence of diminished capacity, which could have involved an attempt by the defence to blame the influence of the Insane Clown Posse on an unstable personality, and seen the climatic scene with the DA ending an aggressive cross-examination with a triumphant, “So it’s not that the band is violent, but that you are!”.

Instead, the show concentrates on the claimed amnesia of the second defendant, leaving the audience with the only conclusion to draw being that Juggalos are deranged murderers. Indeed, that was the conclusion i drew (with a pinch of salt) until I was reminded of the episode by your previous post.

My first question is, does this make L&O a bad show, or merely Dick Wolf a writer with the fatal flaw of being susceptible to being caught out by Quadrant 4 pieces of pop culture. My second question is, does this change the quadrant that L&O falls into? In general I would say that the show is a Quadrant 1 show, if you’re consistently siding with the murderer, then you’re both misreading the show and a pretty bad person. However, in more than enough episodes the issues are vexed enough that depending on which side of an issue you stand (normally a hot button political one, eg. abortion, guns) you could draw an equally correct conclusion, from your own reference points and reasoning, as someone who comes to the opposite understanding I know you wanted to limit subjectivity discussions in this post, but my point is L&O intentionally straddles this line of playing both sides of an argument without deciding which is right, to play to both audiences without alienating either (something they didn’t achieve with the Juggalo episode the internet reaction from that community was a panning). So maybe the test should be a question of having an understanding of the issues raised rather than drawing a specific conclusion. OR we have an Omnipotent Viewer who decides what is the right interpretation of everything and go off that (Omnipotent Viewer is an article I’d like to read).

I didn’t mean to make my first comment a reply to your comment, Norman, since it didn’t address your point – but I’ll address it in this one.

I think that Mark is predisposed in his piece with the danger of being wrong rather than being right, and comparing your correct categorization of art films with one that would get you in more trouble for being wrong — I think it’s a different enough cultural phenomenon to warrant separate classification.

In our fragmented age, the punishment of incorrectness is kind of a scary social force, and it’s useful to look at how it works as a separate mechanism from the zeal for correctness. I don’t think our culture rewards being right nearly as much as it punishes being wrong.

24. I think it makes you a moral monster if you watch 24 and think “if only we had more heroes out there like Jack Bauer, who are willing to do what it takes and not coddle the terrorists by mock-executing their tiny children,” – but I suspect that’s the way a lot of people (including the creators) understand it.

By the nature of this category, there’s gonna be disagreent over what goes into it – by definition, the meaning can’t be obvious, and you ca’t ju st agree to disagree cos one side is saying the other is a bad person. So there are probably no good examples

I disagree. I think the entire purpose of 24 was to ask the audience “how far down this path of darkness and torture are you comfortable going to save innocent lives.” I would bet that people distribute in a pretty neat bell curve between “none” and “whatever it takes.”

I’m really enjoying this discussion of quadrant 4. This article and the comments are this website at its best.

I was thinking about quadrant 1 and the “you’re a bad person for not getting it” description. I think the most common form of misinterpretation in that quadrant is malicious misinterpretation: “I don’t really think it means this, but I’m going to tell other people (or myself) it means this because it supports some point I’m trying to make.”

In this scenario, the “bad” person is the one doing the malicious/intentional misinterpretation, while the consumers of that misinterpretation aren’t necessarily bad, they just don’t have all the information. For them, the item is quadrant 4, because they have no real hope of “getting it” with the information they have, but their judgement is still questionable based on their chosen source of pop culture interpretations.

“The Muppets” is a perfect example of this. Do you really think Fox News analysts think the movie is communist brainwashing? Or do they “believe” this the same way I “believe” that “John Carter” is an alternate history of the Civil War? Those are both examples of intentional misinterpretation, with the difference only that one is tongue-in-cheek and solely for the purposes of entertainment, while the other is my argument about “John Carter” and the Civil War! Ha!

A subset of this is selective misinterpretation, where you take something out of context and make that the meaning for the whole work. I’ve heard people quote “Wall Street” when justifying why they think greed is good, but often they haven’t actually seen the whole movie.

(One of?) the commentary track(s) for American Psycho includes a brief discussion of the apparently frequent occurrence of men who come up to one of the writers saying “I am Patrick Bateman” in a positive way. Anyway, I’m sorry I only have a quadrant 1 example.

I’m not trying to troll, I’m genuinely curious: Twilight.

Where would that go? Because you have the author’s intent: A timeless love story. You have feminist critique: An abusive relationship. And the Twihard interpretation: A love to which we should aspire.

If your idea of correct interpretation means following the creator’s intent, then “Twilight is a timeless love story” belongs to another category: it’s hard to interpret, you understand it perfectly, that makes you a bad person.

Maybe a polyhedron would be more accurate for classifying how difficult it is to understand works of art and how it reflects on others’ understanding of your moral and critical agencies. By process of elimination, quadrant 4 candidates would emerge as the rest of the polyhedron’s surfaces are filled with their own respective candidates. An excessive version of Norman’s approach to defining quadrant 4.

I never claimed any of those interpretations was correct, though. As was suggested in the podcast, and as others have said up above, some people deliberately choose to think something “is” a certain way/thing, knowing, perhaps, it could b something else. For all we know, Meyer (the author) may very well think the books are terrible for women, but she, at least in interviews and such, says they’re meant to be nothing more than a good, old-fashioned love story for generations of women to enjoy. The Twihards may simultaneously think it’s not to be taken seriously as well as a model for their real lives. Feminists may think it’s both harmless literature and the worst thing to come out “for” women since the history of ever.

So then what would constitute making a person a “bad” person in this sense, then? Deliberately picking something you know is different? Or not even knowing the “correct” interpretation exists and embracing one that’s way off- to the point where that latter interpretation makes you look stupid/insensitive/etc.? And which interpretation are we going by when judging the person, the one they willfully ignore (or naively miss), or the one they embrace?

I’m not ranting at you, just typing my thoughts as they come. But to go back to your point, no, I wasn’t trying to say any of those above interpretations are the correct one, because I don’t know if even the author, let alone her fans, do. That’s why I asked in the first place. So I’m not assuming the “timeless love story” interpretation is correct at all.

And I do think, at least in this case, the movies and books are pretty much the same, overall. If anything, the movies are a bit lighter on the creepy-abusive male, needy-passive female factor (obviously my normative opinion is seeping out, here), but also from interviews and such, the people behind the camera are basically stand-ins and mouth-pieces for Meyer. As has been noted above, lots of movies don’t do that with respect to their source material.

One of the problems clouding the issue is interpreting at all. I know of a couiple of mujsicians who just love to hear what people make of their songs and either refuse or make judgements on those interpretations. There may not be a right or correct interpretation, just popular or unusual.

One of the problems with the 4th quandrant is that if it is hard to interpret, any interpretation will have taken some thought and woe betide anyone calling that “wrong”. It’s why 9/11 troofers succeed and also the birthers. Once the compelling arguments have persuaded the adherents, nothing will overcome their loyalty. I guess that makes them bad, per se but it bothers me that they get written off because of their rationalizations.

For an example of a 4th quadrant movie, how about Sucker Punch? This video http://moviebob.blogspot.com/2012/09/the-big-picture-you-are-wrong-about.html makes a compelling argument that Sucker Punch is actually a Starship Troopers type satire which deliberately mocks its own audience. It’s hard to get (as evidenced by the fact that almost no one got it), but if you don’t get it you’re left thinking the point of the movie is that hot girls in fetishwear are fun to stare at, when in reality the point of the movie is you are a disgusting slimebag for thinking that. (Oh and for completeness’ sake here’s part 2: http://moviebob.blogspot.com/2012/09/big-picture-you-are-wrong-about-sucker.html)

I’d put satire in the fourth square, specifically parodies of archetypes that most people automatically take at face value (think Dave Chapelle or Bruno for example). I would also remove the “you’re a good/bad person” part from the equation and focus more on the importance part. Yes, interpreting these things right is very important and character building, but if something is hard to interpret, you’re no exactly a bad person for missing it, nor are you necessarily twisting a clear Message out of malice. More likely, you’re probably set in a context that doesn’t give you the tools to see it.

Also, I’d like to point out that the claeity of Gagnam style isn’t ans unimportant as it seems. It does say something that korean culture specifically is obscure to most of the western world while US culture is not. To use an old example, take Taylor Swift’s “You belong with me” video and show it to a german – they’ll understand. They’ll most likely not understand Gagnam style. There are clear traces of imperialism in how close cultures are to each other.

In thinking on your request, I have two movies to put forth. The first may fit better in “it’s easy to understand” simply because it was easy for me to see, but the majority of people I know didn’t get it, and I don’t know if it makes you a bad or good person. The second would be my prime candidate.

The first movie is James Cameron’s Avatar. Now, first I’d like to put in that this movie wasn’t made on the fly. Cameron had been working and nurturing it for years, which as an artist and storyteller, tells me that there is more context to the story than “guns are bad”.

Secondly, I’d also like to point out that many people who I’ve spoken to who believe in the general stigma of the movie saying that guns and the military are bad, have also blocked up their ears and acted like five year-olds when I point out things in the movie that contradict their point of view.

With that said, I’d like to list some of these examples that counter the idea of the movie being “anti-gun” and “anti-military”.

1) at the beginning of the movie it is said that on earth if you were military you were a hero and any military brought to Pandora was a mercenary and NOT working for the military.

2) if the message had been anti-guns, then it would be a poor choice on the director’s part to use guns on both sides.

3) It was stated that negotiations had already happened and that the people of Pandora didn’t care what they had to offer.

For me personally it was a statement of capitalist pigs doing what they wanted to take what they wanted because out there their own government wasn’t there to stop them. Something I saw as being easy to understand, but it seems to me that so many people found it easier to simply see the “guns are bad” shtick and refuse to see anything else that the message is lost.

Along with that, I think the movie also touched on the importance of taking care of our troops after they leave the military. Jake, who lost his legs was a disabled nobody until his twin died and he was given the chance to do something. Had he not lost his legs, would he have been drawn to Pandora like the other hired soldiers by money and the offering of doing one of the few things he knew how to do? There are a number of men and women who leave the service and don’t know what to do with themselves because what they know is war and they don’t know what else they could be good at. They’re also struggling with PTSD and other psychological effects. Did the other soldiers and mercenaries on Pandora really believe in running people out of their homes? No. And as far as we know they were never told WHY they were there, just that the natives were the enemy. As far as we know, Jake Sully was the only one who was briefed on the unobtanium, specifically because he was being sent in to try and help with negotiations.

*shrug* Like I said, probably not the best fit. So moving on:

The Green Mile

Now… what -is- that movie about anyway? Is it about how blacks are oppressed and charged for crimes they didn’t do? Or how criminals aren’t starkly good or bad? Or how those who keep the peace are necessarily good? Or is it about how sometimes to do a good thing for a friend, we have to do a bad thing to them?

What is the intent of the movie? Is there an intent to it? It’s possible it could be like many asian foreign films where it is more of a painting than a story. Anyone who’s seen it can tell the story, but can we tell the meaning as well?

I wouldn’t say you’re a bad person for not getting it, but more like you’d be a bad person for not trying.