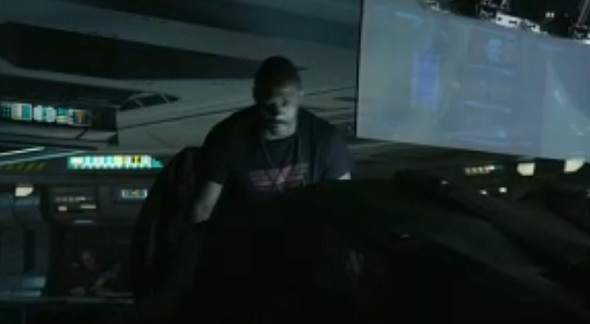

Early on in the film Prometheus, the sort-of-prequel to Alien, the Captain of the eponymous space vessel, Janek (Idris Elba) can be seen wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with the logo of the company for which he’s taking on this mission, the Weyland Corporation. As I sat in the theatre during this scene, I had a very strange experience. The movie hadn’t become all-out ridiculous and terrible yet (it wouldn’t be much longer, though), but I already knew that I wasn’t particularly enjoying it. However, at the moment that Janek appears wearing that shirt, two simultaneous thoughts occurred to me, one of them unsurprising and the other very surprising indeed – One: that shirt is definitely available for sale somewhere; and Two: I want that shirt.

You’re wearing the shirt of the corporation you’re working for? Don’t be that guy.

It was not surprising that I knew the shirt would be available because we all now know and expect that any media product is itself, from a certain perspective, just a commercial for its associated merchandise. If FOX thinks they can make money selling Weyland Corp t-shirts, they’re going to sell them.

The reason that my desire for the shirt was surprising was because I didn’t like the movie. Am I just so brainwashed that I want anything that happens projected on a screen in front of me? I have all kinds of stupid (by which I mean awesome) crap associated with media products that I enjoy, but that kind of makes sense – my Nine Inch Nails t-shirts and Ninja Turtles action figures symbolize and reify my connection to these things, and also communicate something about me and my interests to others who might see them. But I don’t particularly want to be associated with Prometheus, do I? The Frank the Bunny figure that sits on my bookshelf makes me think of Donnie Darko, which is a movie I like, which makes me happy. But if I bought the Weyland t-shirt, according to the same logic, it would make me think of Prometheus, which was a movie I didn’t like, which should make me feel bad. Plus, anyone who saw me wearing the shirt and recognized it would probably think that I was trying to signal that I did like the movie. So what exactly is going on here? I have no desire to own the DVD of Prometheus when it comes out, so what was the source of my desire to own the shirt?

I think that the difference is that the shirt is not just “a Prometheus t-shirt” in the way that my Nine Inch Nails t-shirts are just Nine Inch Nails t-shirts; it’s not an object that represents something related to the movie in the way that my Ninja Turtle figures are representations of the characters from Ninja Turtles. The Weyland Corp shirt is an object that appeared in the movie as itself, which is also an object that now exists in real life. This phenomenon of objects from media getting produced into real-life artifacts is often referred to as “defictionalization,” and it seems as if defictionalization is becoming more and more commonplace not only to help diversify corporate income streams, but as a means of restoring a shrinking sense of the authenticity of art as our consumption of media occurs in increasingly non-physical ways.

Authenticity in art is sort of a weird concept. Philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote an essay in 1936 called “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” wherein he argues that there once was a sort of metaphysical authenticity associated with works of art – by which he meant a painting, a statue, some physical object created by an artist that you could look at, walk around, touch and/or vomit on – but that since around the beginning of the Twentieth Century, when industrialization for the first time made mechanical reproduction a trivial and affordable task, the aura of art was beginning to fade. Because it was now possible to create arbitrary numbers of things by purely automated processes, the authenticity of any given work became essentially null and void.

He identified authenticity with genuineness; an original, say, Picasso, might be atom-for-atom identical with a forgery, but only the original is authentic even though there’s no physical difference between the two objects. Mechanical reproduction, though, can make it so that a work has no original and therefore has no aura of authenticity, and Benjamin identifies the still-emerging medium of film as the perfect illustration of this evolution of the nature of art: one copy of a reel of film is in principle just as good as any other. “From a photographic negative,” he says, “one can make any number of prints; to ask for the ‘authentic’ print makes no sense.”

Benjamin actually thought that the elimination of the aura of authenticity from art was a positive thing, because he felt that divorcing artworks from the mysticality of the aura would help art to progress beyond what he saw as the magical and religious connotations of its cave-painting ancestry and become instead a form of purely political expression. “Mechanical reproduction,” he wrote, “emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual.”

How much more so does the aura decompose as we become less and less dependent on even physical transmission of media for our consumption. A first edition of Ulysses can still sell for €400,000 even though we’ve been mechanically reproducing books since 1440; but in an all-too-plausible future in which all books are electronic, the idea of an “original” of, say, the Twenty-Second Century’s greatest literary masterpiece becomes totally absurd.

The Aura Strikes Back

But the aura refuses to go gently. In the wake of the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, media art has adopted two main tactics in the attempt to recapture the aura of authenticity: performance, the complete abstraction of a work into an event – and defictionalization – the reification of an appearance into an object.

The rise of performance and installation art is an obvious reaction to mechanical reproduction. Instead of the artistic process culminating in a product, you get an event, bounded in space and time, and when it happens you have to be there, or else you miss it forever. This strengthens the aura of the art to a degree even greater than before mechanical reproduction – you can still go see a Picasso wherever it happens to be, but you can’t see The Artist is Present unless the artist literally is present – you can go watch the documentary, but it’s decidedly not the same thing; it’s about the art, rather than the art itself. It’s not as authentic. This is also behind the whole “event movie” thing. Big movies are marketed now not just as entertainment but as participatory experiences. The easier it gets to separate an artwork from its means of consumption, the more important it is to portray that consumption as somehow an artistic statement in itself. Having seen a big movie on opening night has a sense of authenticity to it. Sitting there in the theatre with a few dozen other people, watching it together, somehow feels more authentic than watching a pirated copy of it at home on your iPad or whatever.

Defictionalization is the other thing. When an object that appears in a work itself becomes a work that you can pick up, or listen to, or, most importantly, own. A recentish example of this is the soundtrack to the movie adaptation of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim series of graphic novels. The titular character plays bass in a garage band called Sex Bob-Omb. In both the comics and the movie, it’s explicitly stated that the band is terrible. But while in the comics, because it’s a silent medium, we have to take the character’s word for it, in the movie they’re obviously going to have to play some music for us (unless they decide to go the “tell-don’t-show” route, like with Babydoll’s hypnotic dance routines in Sucker Punch that we never get to see, significantly reducing that movie’s…I don’t want to say “believability,” but certainly its relatability). Director Edgar Wright could easily have chosen to make Sex Bob-Omb genuinely terrible, but since their music is involved in several major plot points, he instead decided to take it very seriously, having Beck compose several original songs for the band, and the actors playing band members’ parts to literally play their parts, guitar and bass and drums and vox all being performed by the people we see on screen.

This is a form of defictionalization. Whereas before the movie, we could, for instance, be a fan of Sex Bob-Omb on Facebook or whatever, it would have been a joke, because the band and their music were not something that actually existed. Now, though, because these songs are now real, you can go out and get the Scott Pilgrim vs The World soundtrack and rock out to them to your heart’s content, this fake band could actually be your favourite band. This is now real music. What that does is ground the world of the movie more solidly in the real world. It makes the diegetic music non-diegetic in a way that connects the viewer/listener with it in a more physical sense than would have been possible before.

We are SEX BOB-OMB and we’re here to make you question the boundaries between fiction and the social order! ONE, TWO, THREE, FOUR!

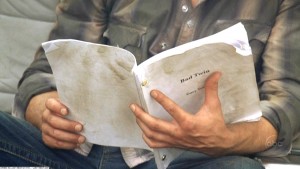

Maybe an even better example of this is the novel Bad Twin, ostensibly written by Gary Troup. Bad Twin is a mystery novel whose author was a character on the ABC TV series LOST. Though the author doesn’t ever appear onscreen, dying namelessly in the pilot episode, another character can be seen reading the original manuscript of the book left behind later on in the series. The version of the novel in our world (currently out of print, but which you can easily find used on Amazon or wherever) was largely a marketing ploy; fanatical fans would buy anything that they thought would give them some hint as to what the hell was going on with that show.

While the novel was passably good, it wasn’t brilliant, and though no secrets were given away, certain themes emerged that, in retrospect, further elaborate on the tropes and concerns that the show was interested in but either never got around to using, or decided to keep ambiguous, depending on how you felt about the finale (I, for the record, liked it). The fact that Bad Twin is framed as something real, an actual physical book nevertheless written by a completely fictional person, again, connects the reader who cares into the world as depicted by the show in a more visceral sense than just sitting in front of the television does. It breaks down the need to suspend your disbelief a little bit more, because here’s a real object, an actual product, a book just like any other book you might want to read – and books are written by people. Real people. Somebody had to write it, and the bio on the inside cover flap tells you that it was Gary Troup, who mysteriously disappeared along with the rest of the inhabitants of Oceanic Airlines Flight 815. The reality of that unreal event, its aura of authenticity, is enhanced by your new ability to hold and read something that you can watch Sawyer hold and read as you watch the show.

Got your manuscript! A few notes . . .

Which brings us back to Prometheus and the Weyland Corp t-shirt. Why did I want it so much, even though I didn’t like the movie? I think it could be because I didn’t like the movie. But I wanted to. Oh, how I wanted to like that movie. Because I’m a fan who’s invested in the world in which the Alien series takes place. I even liked David Fincher’s oft-bemoaned Alien3. Quite a lot, in fact. But this t-shirt incident reminds me of how much I ended up desiring the really awesome New Rock boots worn by Winona Ryder’s character, Annalee Call, in Alien Resurrection, the Joss Whedon-scripted fourth installment in the series that deserved to be much better than it was. Those were real boots already, expensive, stompy, $400 boots that you could go out and buy. And that fact grounded the movie, somehow made it more believable and less of a travesty.

I think that’s what’s going on with the t-shirt thing, too. Yes, Prometheus was dumb. But the more you accept the plausibility of some event, the more connected you feel to it. If you can wear a t-shirt that was also worn by Janek on the bridge of the Prometheus, it lends at least a little bit of plausibility to the whole train wreck. Probably that’s an irrational reaction, but it also works. Our reactions to art – even failed art like Prometheus – don’t have to be rational, as long as they’re genuine. Owning and wearing a piece of that world makes us feel like we have a stake in it that we otherwise don’t, because the characters are so stupid and the scenario so ridiculous. Defictionalization gives us a means of partially rehabilitating Prometheus.

Not too long after watching the movie, I did, in fact, see that shirt for sale at Hot Topic. I didn’t buy it. However, I’m holding out hope that the Director’s Cut of Prometheus may turn out to be salvageable. Remember Blade Runner? Remember that awesome gun Deckerd has? Same thing. It’s not too late, Ridley Scott! It’s not too late to redeem yourself!

Sex Bob-omb aren’t meant to be objectively “bad” in the Scott Pilgrim books or film. Naive, stupid, misjudged, sure – but also fun, raucous and energetic. It would be terrible if they were the only music in the world, but it would be terrible for the characters if Sex Bob-omb didn’t exist. The books and film make a very solid case for garage bands being the one of the greatest things in the world.

“Failed art” is also a bit of a provocative statement, especially in relation to a financially successful and critically well-recieved production like Prometheus. You may not like it and you may not be on your own, but Fox don’t have to sell t-shirts to redeem themselves – they just took in $330 million dollars and they haven’t released to retail yet. Contrast that with Scott Pilgrim (a film I genuinely adore) – critics liked it only a little more than they did Prometheus, but audiences liked it a lot less. Is it more of a failed art or only slightly less of a failed art?

From Scott Pilgrim, Vol I:

“Hey Kids! Now you can play along with Sex Bob-omb at home! It’s easy because they’re kind of crappy!”

I always got the feeling that Sex Bob-omb was the type of band it was great to be in – as you say, raucous and fun, but more in the nature of a hobby for the characters than a serious musical venture. Bad bands are still a lot of fun for the people in the band, and note that what kills Sex Bob-omb in the end (in the books) is Stephen’s attempt to turn it into a “real band”.

I find your ideas about defictionalization very intriguing, even if I completely disagree with you about calling Prometheus “dumb.” You didn’t enjoy it, fine; it’s currently the best film I’ve seen in theaters this year.

Back to defictionalization. I think the filmed object/T-shirt/whatever, when made available for ownership, becomes a totemic artifact which, in some psychic manner, causes the owner to enter the fictionalized world. It’s like the production is the two-way street, the channel by which fictionalized objects are reproduced and real-people become slightly fictionalized.

On a side note, your ideas on defictionalization complement Grant Morrison’s concept of the “fiction suit” very well. He talks about it in Supergods, his book on the history of superheroes. It is definitely worth reading.

There’s a site that specializes in selling t-shirts featuring fictional company or military logos from movies or tv shows, lastexittonowhere.com. Outpost #31, OCP, Winchester Tavern. A little pricey, but fun ideas. I’m pretty sure they had some Weyland-Yutani Corp shirts available before Prometheus came out, in reference to the earlier Alien movies. (I guess Weyland merges or gets bought by Yutani at some point after Prometheus, before Alien?)

Twin Peaks put out a couple defictionalized bits of merch: the Secret Diary of Laura Palmer (written by Jennifer Lynch) and “Diane…” (the tapes that Agent Cooper was supposedly dictating for a secretary to transcribe later). I vaguely remember stores selling “Mumford Phys Ed Dept” t-shirts back in 1984 or so, based on the design that Eddie Murphy wore in Beverly Hills Cop.

When it comes to assessing art, YMMV, there’s no objective good or bad. But I agree with your assessment that Prometheus was dumb. As far as the story and characterization, there were lots of amateurish mistakes.

Thanks for telling me about the Twin Peaks stuff, I have so looked up where I can find that online now.

There’s also a travel guide to Twin Peaks that includes hints as to what they had planned for the third season (as, possibly, does the Cooper autobiography).

I own that Weyland-Yutani shirt. It has been my favourite shirt for about five years now. Excellent quality and very cool (so long as I make sure I only associate with the right sort of people). I would recommend that site to anybody here as I think it has just the right sort of knowing commercialism that would likely appeal to overthinkingit.com people.

So far as the films go, Weyland and Yutani come together at the end of AvP: Requiem, but as Prometheus rewrites that history then yes, we can only assume that Weyland and Yutani meet up sometime in the future.

Awesome!

I wore this through a few airports recently, and the only person to comment was an adorable, little, old lady working at the security check-in in Pittsburgh, PA: http://6dollarshirts.com/product.php?productid=12047&mail=251

I was surprised- a little old lady “gets is,” and the young guy beside her, brooding over the screen the way Bruce Wayne broods over… everything… doesn’t?

Hot Topic is pretty big on the fictional corporation merchandise- I gave my sister an Umbrella Corporation shirt from there for Christmas, for example.

I can’t help but feel a little cynical and believe there’s a (perhaps subconscious at least, perhaps sometimes deliberate) desire to be somewhat exclusive, in-group, hipster-ee with things like that, though. As in only a true fan would 1) go so far as to purchase that merch and 2) recognize it on someone else. It’s a way of saying you’re that awesome, because you understand, and to feel part of that small, elite group that would. But it may not necessarily be an outward expression of being better than anyone else. Admittedly, I feel kind of awesome when I wear my Wayne Enterprises shirt, and my sister feels likewise when she wears the Umbrella Corporation one; we don’t go around sniggering because people don’t outwardly acknowledge them, though. It’s the difference between arrogance and confidence, and I suppose depending on the person, you’ll get different concentrations of each.

And it’s different than wearing the series logo or something. It’s one thing to wear the Batman symbol on your shirt; the Wayne Enterprises logo is a different story, sort of like a higher step or level on the hierarchy of fandom.

Also, the books written by the titular character in Castle, another ABC show, are available. They’re not that good. But they keep selling, and they keep getting made. And here’s a bit that’s sort of the opposite of your Prometheus experience, Belinkie: I really, really enjoy the show, and there’s a part of me that would really love to have those books, just to say I did. And, truth be told, I gifted the first one to a friend, and she was giddy as can be when she opened it up; intriguingly enough, even after telling me the book was a piece of crap, she keeps it on her TV stand in a place of honor between a snow globe that belonged to her grandmother and a family portrait. The most reasonable explanation is because her genuine affection for the show trumps her dissatisfaction with the book as a mystery novel. As you said, it’s a piece of the Castle world, and she can own it, and thus be a part of that world a little.

I do think your desire for that specific shirt stems from your overarching love for the Alien movies, as well as your desire for Prometheus to be good because of that love. And there’s really nothing wrong with that- I think it’s a concrete example of how art can move us, stir us inside and cause feelings and thoughts that are just as confusing as everyday life. A big part of day-to-day existence is various degrees and forms of cognitive dissonance and contradictory feelings and behaviors. You know your favorite route to the store is filled with traffic, but you take it anyway; you hate beer, but you agree to go have a brewskie with the buds; you keep the channel on TNT to watch Air Force One when it starts soon, despite the current movie being Bio Dome. I’m starting to ramble, but my point is there are myriad ways our connections to objects and each other manifest themselves, sometimes simultaneously; and it’s natural to gravitate toward the positive feelings and experiences, even if it means the route isn’t the most pleasant. Ends versus means and all that kinda jazz.

Oh, and as an aside, the viewing experience of Prometheus hauntingly parallels that of Terminator: Salvation.

Very interesting piece. ‘Defictionalization’ got me thinking about an entirely more trivial scenario which has perplexed me over the years and does prompt serious thoughts about my overthinking of it. This may have been covered regarding a similar scenario elsewhere – if so, let me know.

In Australian soap opera ‘Home and Away’ back in the early 90s (I think) actor Craig McLachlan played a high school teacher. Scenes regularly took place in the local diner, where the jukebox was always on. On numerous occasions, McLachlan’s character would be in the diner, and the jukebox would be playing songs from McLachlan’s ACTUAL album (he had scored a number of top 10 hits around the world). It always drove me to distraction that no-one else in the diner would say ‘hey (name of teacher, which I have now forgotten), do you realise you look EXACTLY like this guy *gestures at jukebox*?’ Obviously it was simply a way of plugging an actor’s songs, but it crashed through the fourth wall and has perplexed me ever since.

I think a less throwaway form of defictionalized literature than “Bad Twin” would be the Rick Castle series of detective novels, based on the ABC TV show “Castle”. In the show, Rick Castle (played by Nathan Fillion) is a popular detective novelist who pulls strings to be attached to a real-life detective, who is used as an inspiration for his new heroine, Det. Nikki Heat. In 2009 ABC published the first Nikki Heat novel, “Heat Wave”, under Richard Castle’s name through Hyperion, and it reached #6 on the New York Times’s bestseller list. The fourth novel, “Frozen Heat”, is due to be published Sept. 11, 2012.

I just finished reading the other comments, and I see Gab already mentioned this. Sorry.

One of the first examples of this that I really noticed is “The angels have the phone box” shirts from Doctor Who. It’s interesting, because the shirt is never actually shown in the show – a character just says “I’ve got that on a T-shirt”, and now there are countless variants on the design floating around. None of them is the actual shirt from the show, because it was never shown, but all of them have that defictionalised aura – possibly moreso, since people make them themselves.

For my part, I wonder if it was an intentional ploy by the show’s producers to make these shirts into a thing. Like “you’re not a true fan unless you’ve made your own ‘Angels have the phone box’ shirt.”

That was a really enjoyable post, although I’m probably being stupid but I couldn’t see who the guest writer is?

I wrote my undergrad dissertation on film merchandise: “film merchandise: bridging the gap between fiction and reality” in 2000 – I love all this stuff! At the time Toy Story 2 had just come out and the merchandise confused me as much as it seems the T-Shirt confused you. The dolls that were sold (Woody and Buzz) weren’t just representations of characters in the film – they were dolls in the film so the dolls in the shops seemed somehow REAL. Forest Gump was another good one where they actually opened a chain of Bubba Gump shrimp restaurants – this is all a while back now. I think one of the reasons you wanted to get the T-shirt, and the reason I love hearing about all these ‘defictionalizations’ (which I’d never heard of) is because we think what they have done is clever – irrelevant of the film it originated from. True, people often buy these things because they want to extend their ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ (Samuel Taylor Coleridge) beyond the confines of the cinema, but I think a lot of it has got to do with the fact that we like to show that we ‘got it’.

I’ve extended my own interests in WB’s aura and authenticity in an article due to be published in The Information Society. It was called ‘Larger than Life: Death in the Age of Digital Reproduction’ for those with a knowledge of Benjamin, but I changed it to ‘Larger than life: Digital Resurrection and the Re-enchantment of Society’. If you’re interested I’d be happy to send you a copy – lots of similar interests I think! I’d like to see more of your work so it’d be great if you can get in contact.

This article I think really describes why fans respond so well to really good viral campaigns.

The Dark Knight famously had an awesome viral campaign that had fans performing missions for the Joker finding websites for organizations and businesses in Gotham, watching fake news stories and uncovering backstory for the time in between Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

Part of the viral campaign was the fictional organization known as “Citizens for Batman.” They had a website and fake forums and everything. It was a window into the fictional world. At one point in time there was a mission to turn in “Batman sightings” where people here in the real world were encouraged to stage or photoshop pictures of Batman. In return I received a package of Citizens for Batman bumper stickers and keychains along with a letter from the organizations leader “Brian Dogson” who posted on the forums often as “B-dog”.

Fast forward a few months to when The Dark Knight Finally comes out. In the film, members of Citizens for Batman are seen in one of the opening scenes of the film, dressed in hockey pads and acting as imposter Batmen.

Later one of these fake batmen is captured and killed on film. The Joker asks him what his name is. His reply “Brian Dogson”.

For me watching the film, after having interacted with this fictional character, the scene packed a serious punch. What could have been just an unfortunate end for an extremely minor character became one of the most affecting moments in the film for me. Its a media experience that I will never forget.

It’s very strange for me to read this sentiment of “it’s a real object, therefore it lends the weight of authenticity to a piece of fiction”. For me, peripheral and franchise objects almost universally cheapen my connection to the fiction, and break my suspension of disbelief, in much the same way that a video game cutscene, lovingly rendered in hi-def animation, breaks my connection to the lower-quality but *consistent* gameplay graphics; I’ve gotten used to them, and they have become inextricably linked with the characters and story. The change is jarring to me, because it’s in a different medium. It causes me to actively think about believability and suspension, which for me is usually the death-knell of connection. Are there any others like me reading this? It seems from the existing comments that mine is a minority view.