Minority Report, released ten years ago this past June, drew critical praise not just for the intensity of its action or the sophistication of the free will questions its team of crime-fighting precogs provoked. It also boasted a unique, glossy vision of the future, more exciting and at the same time more plausible than anything audiences had seen. Crime scene techs studied footage from thousands of surveillance cameras on swipeable touch screens, while advertisements adjust themselves to conform to the user viewing them.

A decade later, that sort of technology has become commonplace. And many of the movie’s devices and concepts are in development – electronic paper, insect security robots, crime prediction software. But that’s not what this is about.

Rather, this article is going to ask which came first.

In order to come up with his vision of 2054 D.C., Steven Spielberg famously convened a three-day think tank of technologists and futurists in 1999. Those in attendance included Stewart Brand (editor of the Whole Earth Catalog), writer Douglas Coupland (Generation X, Microserfs) and VR pioneer Jaron Lanier (also author of the anti-technocratic manifesto You Are Not a Gadget). Between them and the architects and doctors in attendance, they created a future that was sleek and efficient, but with plenty of grime left between the seams.

One of the most striking design elements of the film was Chief John Anderton’s translucent touchscreen display. He used this to quickly organize and manipulate vast amounts of data. No one ever explained how this interface worked – which I loved; excessive exposition is the curse of most science-fiction – but it seemed intuitive. It wasn’t always clear which gesture of his corresponded to which action, but he was clearly commanding something.

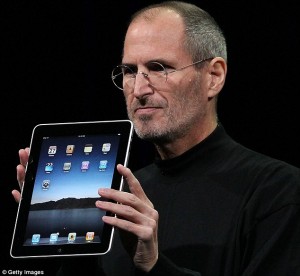

This design was a product of Spielberg’s think tank, as recorded by Alex MacDowell in the movie’s “2054 bible,” and the vision of technology advisor John Underkoffler. Spielberg told Underkoffler he wanted an interface that looked “like conducting an orchestra.” The console that we saw was the result. Today, ten years later – and over a generation before the movie’s 2054 start date – you might be reading this article on a tablet that incorporates that same design.

So which came first? Did Minority Report predict the iPad? Or did Steve Jobs set out to make a computer like Minority Report?

While Jobs may have had a vision of gesture-based interfaces for years (given the hype surrounding Jobs’s design chops, it’s hard to say for sure), there’s a reason the iPad came out when it did. Apple wanted to get into tablet computing as early as 1993 with the Newton MessagePad, but the technology couldn’t support it: AAA batteries, poor handwriting recognition and overall lack of connectivity. It took the saturation of the U.S. cell phone market to create an environment, both in terms of market penetration and cellular infrastructure, where a portable computing device with touch-sensitive interface could be feasible. Then, because demand for phones outstripped demand for notebook computers, Jobs had to build the iPhone first. Fortunately, with some help from Cingular, Apple was able to build out the iOS to the ubiquitous presence it is today. The iPad may have been “an idea whose time has come,” to quote Victor Hugo, but it was also an idea whose time couldn’t have come any sooner.

And part of the enthusiasm for touchscreens may have, of course, come from Minority Report. Seen by millions of Americans while in theaters, it put the idea of swiping through multiple screens into the popular consciousness. It’s an almost statistical certainty that at least one of the members of “Project Purple,” Apple’s 2004 think tank that conceived the iPhone and iOS, saw Minority Report.

So, on the one hand, Apple’s interest in tablet computing and the touchscreen interface predates Minority Report. But Apple’s successful tablets and touchscreen products, like the iPhone and the iPad, postdate Spielberg’s movie. So did Minority Report predict the iPad or cause it?

Cosmo: Posit: People think a bank might be financially shaky.

Martin Bishop: Consequence: People start to withdraw their money.

Cosmo: Result: Pretty soon it is financially shaky.

Martin Bishop: Conclusion: You can make banks fail.– Sneakers

For decades, the West has been building a future in the shape of past prophecies. Popular culture inspires a generation of young thinkers, who grow up, enter the lab, and then build the visions of their childhood. The Department of Defense keeps investing money in heat rays, despite their limited utility or cost-effectiveness. The notion of colonies on the Moon or Mars may have inspired millions of physicists and engineers, but it’s indisputable that it would be easier to colonize Antarctica than the Sea of Tranquility. And modern cell phones owe as much to Star Trek-era communicators as to WW2-era radios. These visions of the fantastic drive us onward, whether they’re realistic or not.

A flip-top? What is this, 2005?

Of course, the authors who gave us these visions – H.G. Wells, Ray Bradbury, Arthur Clarke, Gene Roddenberry, and the like – usually weren’t writing as prognosticators. They wanted to create fantastic scenarios and depict adventures. Roddenberry in particular wasn’t concerned with how warp drive or beaming might work. Despite the generations of physicists who’ve followed, insisting that warp speed might one day be possible if certain theories prove true, it’s clear that this was one of Roddenberry’s less realistic visions.

So some assertions about a non-existent universe prove true. Some assertions about a non-existent universe prove implausible. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it’s also a key plot point in Minority Report.

Agatha (Samantha Morton), in one of Fenzel’s least favorite scenes in 21st century cinema, tells John Anderton (Tom Cruise), several times and at piercing volume, that knowing the future allows him to change it. However, by the time the movie enters its final act, we know that to be false. The process of discovering the future that he wants to change puts Anderton in a position where he inevitably completes it: Leo Crow grabs the gun that Anderton holds, discharging it in the scuffle. Agatha insists Anderton has a choice, but maybe there are too many factors beyond him (Crow’s intentions, Witwer’s actions, Burgess’s plans) for him to stop it, just like no one person could get the Pentagon to stop researching heat rays. The future is set once enough causative factors start pointing in the right direction.

Does seeing the future change it? The plot of Minority Report says no: Anderton knows his future, even dragging a precog along with him, and can’t even postpone his future by more than a minute. The outcome of Minority Report as a cultural property says yes: by making Anderton’s interface a gesture-driven touchscreen, rather than a voice-activated holosphere or some other mechanism, Spielberg and Underkoffler shaped the future of portable computing and front-end design.

This raises the question: is a prediction that does not match the future it predicts incorrect or transformative? If the precogs see a murder (John Anderton killing Lamar Burgess, for instance) and it doesn’t happen, is it because they got it wrong or because the act of prediction changed the future? If 2054 comes and the police aren’t using spider robots to scan tenements, is it because Underkoffler was wrong about robotics or because municipal police universally agreed that spider robots would be way too creepy? How do we distinguish our futures?

Sokka: Hey you, I bet Aunt Wu told you to wear those red shoes, didn’t she?

Villager: Yeah. She said I’d be wearing red shoes when I met my true love.

Sokka: Uh huh. And how many times have you worn those shoes since you got that fortune?

Villager: Everyday.

Sokka: Then of course it’s gonna come true!

Villager: Really? You think so? I’m so excited!– Avatar: The Last Airbender, S1E14, “The Fortuneteller”

This is the trouble with all predictions, especially the public ones. Telling someone what’s likely to happen biases them in that direction, just as observing a particle impacts it with a quantum of energy. Making a prediction and keeping it secret removes this risk, but takes all the fun out of making predictions.

So you have two options. One is to seed the future with thousands of predictions, some likely and some outlandish. If enough of them come true, you’ll get a reputation for amazing foresight (like Jules Verne). The other, as Underkoffler did with gesture-based computing, is to make your vision of the future attractive enough that others will step up and make sure it comes true.

There’s a Terminator 2 quote that might fit here, but I’m not giving Mark the satisfaction. I know how he’ll react, though.

One thing I never got was how three precog were meant to control all the murder in the U.S, I mean they would simply have been too much crime for them to be able to see it all

They weren’t supposed to. It’s been a while since I’ve seen the movie, but I believe the murder prevention only took place in a zone around Washington DC.

Lavanya’s right – they were only in the DC area at the opening of the movie. The whole murder conspiracy was part of an effort to expand the program nationwide (though they never say how they’ll do that, since getting more pre-cogs would require deliberately giving pregnant mothers drugs so there babies would become pre-cogs. Kind of dark, even for Minority Report.

In my view, the technology that comes closer to what was envisioned in Minority Report, is Microsoft Kinect, because it’s a three-dimensional input system. You don’t have the orchestra-conducting like on an iPad yet (it’s a little bit clumsy in tracking your body movements) but I’m pretty sure that’s going to come as the technology gets more fine-grained and reliable. Add some 3D technology (already available on TV screens), and you have your science fiction come true.

Almost – we still need the software that provides the bridge between the input system and the large amounts of data. Waving your arms and gesturing with your hands and translating that into virtual movements is one thing. But how does that help you in plowing through tons of data (visual, texts, audio). THAT actually seems the hardest to implement in our current time.

Ah, yes. You must be referring to the philosophical keystone of the Terminator franchise and rallying cry to all who vow to fight the dire predictions for our future: “Chill out, dickwad.”

OK, now for some more substantive commentary.

We’ve been talking about technology up to this point, but this is also relevant to other fields like economics and politics, where predictions are abundant but consequences for inaccurate predictions are virtually nonexistent. Check out this episode of the Freakonomics Podcast if you want to hear more on this topic.

I guess this is a little less “no fate but what we make” and more “shit happens it’s folly to try to predict it.”

What I find with M.R. is the plausability of the forced tech. Everything that was used to advertise, like the eyeball ID scanners into the store “for a more personalized shopping experience” and the cereal boxes, will happen far more sooner than anyone thinks.

The police robots and funky cars much, much later.

One of the things about the funky interface pieces (see also The Island with the MS table) is that none have input abilities. Everything is about manipulating the already present data. It means that these things would never be common place but be playthings of upper hierachy mgmt with floors of drones doing the input down below.

As an aside, the biggest flaw with MR is the last 5 min. It’s meant as a given that success was shutting down the precog unit. Why? It was a massive success in that it prevented all murders in its area. The lawsuit from the first murder after the unit shutdown would be ferocious I would wager.

The main point about the whole precog thing was that it was possible for the precogs to be wrong… which means that, given the cops stopped the person from doing it, they can’t prove, other than the possibly flawed precog viewing, that the murder was going to happen. Intention is going to be a tough sell to a jury…

(insert quote here about waiting after someone has thrown a brick through a window before arresting them, as opposed to acting first and allowing the ‘I wasn’t really going to do it’ excuse…)

Rather than the possibility that the precogs might be wrong, my aversion to the whole scenario was that people were being punished for crimes _they did not commit_. The purpose of the precog unit was to *prevent* crimes by allowing officers to stop them before they occurred. Once that had been achieved, there was no crime committed – right? So why were the people being locked up for who knows how long? They were being punished for simply *thinking* about a crime….

But, but, but…

It *worked*. There were no murders. It was never explicitly stated what the percentages were to generate 0 murders, but it certainly wasn’t a 1:1 ratio. That means, yes, precrime grabbed innocent people. As John said, did some of them change their minds once grabbed? What is the process for precrime? Automatic psych counselling? Immediate arrest? Where is the line drawn?

And of course, we come to the minority reports themselves. Where they generated by one precog more than another? Does that make that one more or less reliable? And we’ll bypass the whole issue of the director since that is more a policy function. Remember this is a pilot project, there are bugs to work out.

Still, the object was met, no more murders.

That was always kind of my thought on this one as well. The old argument that “Better 10 guilty men go free than one innocent man go to prison” applies primarily to RETRIBUTIVE justice, applied after the fact. Where we’re talking actually PREVENTING crime, that logic may or may not apply to same extent.

Put another way, what margin of error would be acceptable to make the precog scheme work? If the false accusations are 1 in 3, that would give one pause at punishing people based on their predictions. If the false accusations are only 1 in 1000 or something like that, would that be acceptable “collateral damage?”

It seems to me that the solution to the “Minority Report” problem (i.e. there may be more than one possibility) is just to lessen the punishment for “pre-murder.” Anger management classes and a fine are probably more than enough – you still have the pre-cogs, so it’s not like there’s a risk that if you let them go they will go out and kill people. Probably only use the mind prison for serial pre-offenders.

I’d have liked to have seen a scene (I forget if it happened with the scissors guy) where the cops come and stop a pre-crime and the murderer just breaks down with relief that they’ve been stopped in advance. Just for interest – the reactions of the pre-criminals, esp. on red ball – are likely to be strongly emotional, but would they be more relief or anger?

I’m sure there’s a vital point to be made from _Payback_, but I can’t think of it.

Gah, I mean _Paycheck_, dammit!

It’s possible that both the technology in MR and real-life touchscreens could come from an earlier, possibly even instinctual, source. I mean, when people see an object — even on a computer screen — it only feels natural to want to move it with your hands, not a seemingly disconnected button. We unlearn that instinct pretty quickly, but there’s still something about modern GUIs that naturally leads to dragging things around with your fingers.

I remember the first time my grandmother sat in front of a computer (probably in the late 90’s when she was about 80. I told her that she needed to move the mouse in order to move the pointer on the screen, and she immediately picked up the mouse and moved it around in mid-air. Seemed to her that it was only natural to move things in the three-dimensional space.

“Does seeing the future change it? The plot of Minority Report says no: Anderton knows his future, even dragging a precog along with him, and can’t even postpone his future by more than a minute.”

Enjoyed the article, but this point is completely wrong. Anderton DOES change the future. Instead of him shooting Leo Crow like the precog’s vision, he tries to arrest him and Crow grabs the gun and shoots himself.

Also, at the end, John Anderton doesn’t kill Lamar, the vision had Lamar killing Anderton. Instead, Lamar kills himself, showing again the future can be changed.

It’s amazing how well this movie sticks even if I haven’t seen for a decade.

The whole premise of M.R. is that the future IS changable. Not one of the precog’s visions comes true because of the precrime unit. That’s their whole reason for being.

And as for Anderton, also don’t forget he is the focus for the M.R. The precogs agree on the incident, the time, the place and at least one of the participants, but the actual incident is murky. As it turns out, it’s because even tho someone dies, it’s a suicide which must be different than murder. It’s never explicitly setup in the movie that I recall.