Please enjoy this post from frequent guest author Ben Adams.

In the seminal work The Ghost Ship Moment, Matt Belinkie makes the following observation:

…certain movies are divided into two parts: the part before the characters know what kind of movie they’re in, and the part after. The Ghost Ship Moment (or GSM), in its most basic formulation, is when the characters in a film learn what you know…

The Ghost Ship Moment relies on a gap in information between the audience and the protagonists—though the teenagers on screen are excited about going to the lake for a weekend of alcohol and fornication, the audience is excited for the violence to start. After the first body falls out of a tree, the teenagers catch up to the audience and realize that they are in danger.

However, the gap in knowledge almost never closes entirely. In Ghost Ship, Julianna Marguiles’ character “Maureen Epps” catches up with the audience when she finds out that this ship has g-g-g-ghosts! But the audience still has an advantage: Julianna Marguiles got top billing, and the audience has seen horror movies before, so they know that her character is probably going to be the “last girl.” Despite the dangerous events, the audience is never really expecting her to die. Maureen Epps (the character), though, never knows she’s in a movie; she’s running away from ghosts the whole time, scared of dying at any second.

It is almost impossible to walk into a theater or sit down in front of a TV without at least some prior knowledge. Even if you haven’t seen a trailer, read a review or heard a plot synopsis from a friend, you’re likely familiar with the genre and the well-known actors. All of this combines to create a firm—and usually accurate—set of expectations. We know the Meat-Hook killer is going to kill the arrogant jock, so from a plot standpoint we’re not really interested in the fact that he just got killed; we’re interested in seeing how the characters react to learning what we already know.

On rare occasions this relationship is flipped around. Sometimes the audience’s expectations are inaccurate, and the audience finds out just what kind of movie it is really watching. Whether from deliberate misdirection or poor marketing, the movie that we’re expecting to see can sometimes be very different from the movie that was actually made. It is possible, then, for there to be a Reverse Ghost Ship Moment, where the audience’s prior expectations of a movie are turned around and used against them.

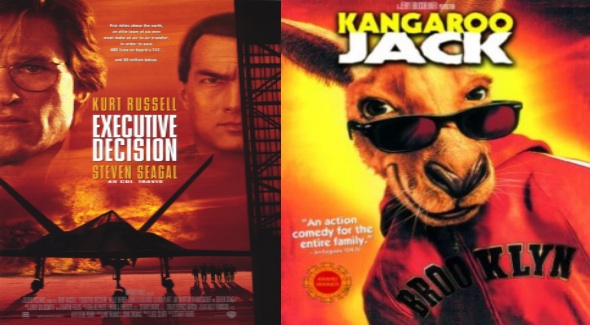

Two specific types of “reverse” Ghost Ship Moments tend to crop up more often than others, and in the spirit of the original Ghost Ship Moment, I’ve chosen to name them after suitably B movies from the late 90’s and early 00’s.

The Actor Bait-and-Switch or “The Executive Decision Moment”

At the opening of Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol, IMF agent Ethan Hunt is in a dire situation. Imprisoned in Russia, he needs to fight his way through an endless array of hard-ass Russian prisoners and prison guards. The character Ethan Hunt believes that anything could go wrong, and he could get stabbed in the gut at any moment. Of course, we know he really couldn’t—they don’t pay Tom Cruise to get shived in the opening scene of the movie, and there’s no way he’s not going to make it to the final credits sequence.

Ho-hum, I’m sure he’ll be fine.

When we see a top-billed movie star on screen, we generally expect that they are there to stay. If they die, it will certainly be no earlier than the third act, where their passing can be given the appropriate amount of dramatic emphasis. Similarly, we expect that the movie’s “star” will feature prominently in the plot: the guy getting paid $20mil to be there is probably not playing “Checkout Clerk #2.”

Which is why it is so surprising when the audience realizes that the “star” isn’t the star of the movie at all. If you went to see Executive Decision in 1996, you were probably expecting “Die-Hard-on-an-Airplane” starring Steven Seagal as Lieutenant Colonel Austin Travis, killing terrorists and snapping necks with his side-kick Kurt Russell. This expectation works out until about 15 minutes into the movie, when Steven Seagal is killed in a freak stealth-fighter-to-747-mid-air-transfer-accident.

The audience has just hit the “Executive Decision Moment” (EDM), where the face on the poster and in the trailer isn’t hero or villain, he’s just some guy who dies so the heroes have something to fight for later in the movie. Before the EDM, the audience is watching a Steven Segal/Kurt Rusell Movie movie. After the EDM, the audience is watching a Kurt Russell movie (whether or not that’s a good thing is left as an exercise for the reader.)

Sir Not Appearing in this Film

In Executive Decision, the mismatch between the film’s marketing and plot was a conscious decision by the moviemakers to play on the audience’s expectations. In other cases, false expectations are the product of an ex post facto decision made by the film’s marketers. The marketing campaign for 2005’s Stealth played up Jamie Foxx’s role heavily as a result of his 2004 Oscar nomination for Collateral and win for Ray.

Stealth had been filmed well before those successes, so Jamie Foxx, who between filming and release had become the biggest star in the movie, is killed before the halfway point of the movie in a freak stealth-fighter-fighting-an-evil-artificial-intelligence-in-a-narrow-canyon accident.

The actor bait-and-switch can happen in less dramatic ways than stealth-fighter-related death. The trailer for 2011’s Limitless clearly sets up Robert DeNiro as the main nemesis of Bradley Cooper’s medication-enhanced main character.

The movie itself opens in media res with Bradley Cooper deciding whether or not to throw himself off of a high-rise balcony before flashing back to the beginning of the story. If you had seen the trailer, the clear expectation is that DeNiro’s robber-baron banker is going to be the prime driver for whatever trouble Cooper is in at the opening of the movie.

In actuality, DeNiro’s character is primarily a background character until the very end, while the Russian mobster “Gennady” who barely appears in the trailer proves to be the “big bad” of the movie. The confrontation between Cooper and DeNiro shown in the trailer is tacked on to the very end of the film and is resolved with just a handful of lines of exposition.

An Executive Decision Moment isn’t, however, a complete inversion of expectations. It’s surprising that the marketed “stars” of Executive Decision and Stealth are killed so early on, but that’s just a change in the face of the movie, not the shape of it. Executive Decision is still Die-Hard-on-an-Airplane, only with the part of John McClane being played by Kurt Russell instead of Steven Seagal.

Genre Mismatch or “The Kangaroo Jack Moment”

After watching that trailer, anyone going to see Kangaroo Jack would assume that they’re about to see a whimsical kid’s movie in which the sunglass-wearing, sass-talking kangaroo is the star. Meanwhile, over here in reality, the movie is an adult-skewed comedy about Jerry O’Connell trying to recover the money he’s supposed to be delivering to the mob in Australia from a (non-talking/non-magical) kangaroo that runs off with his hooded sweatshirt. The kangaroo only talks for one short scene in which the main character is hallucinating.

At the end of the hallucination scene, the audience has hit their Kangaroo Jack Moment – they’ve realized that that’s it, that’s the only talking kangaroo they’re going to get. They’ve been duped by whichever marketing guru at Warner Brothers decided that the world would only ever to pay to see a movie about a kangaroo that steals a mob courier’s blood money if the kangaroo can also talk for some reason.

The Kangaroo Jack moment is the moment you realize that the movie you’ve paid to see and the movie you are actually seeing are two very different things. This type of complete genre-mismatch isn’t unique to marsupial heist movies.

In this two-minute trailer for Bridge to Terabithia, a solid minute is devoted to talking trees and fantastical creatures. The trailer is clearly trying to sell a high-fantasy action vehicle a la The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The actual Bridge to Terabithia has only a small handful of scenes with fantasy and action, and all of those scenes are quite explicitly in the imaginations of the main characters—the action sequences are meant only to be representational of the movie’s larger, sadder, story about childhood friendship.

Marley and Me’s trailer uses a combination of “Bad to the Bone” and a series of zany canine hijinks to sell you on a light-hearted family comedy revolving around a dog. Spoiler alert: if you Netflix either Marley and Me or Bridge to Terabithia looking for a light popcorn movie to unwind after a rough day, STOP. JUST STOP. Neither of the movies’ marketing departments got the memo that these movies are made of nothing but pure sorrow and tears.

While there may not be a specific moment that the audience realizes they’ve been had, both of these movies are far, far different movies than what is represented in the previews. As a result, their devastatingly sad endings pack that much more of a gut punch precisely because of the Kangaroo Jack moment.

The Ghost Ship Moment is interesting because it highlights the power of expectation in film—the asymmetry of information between audience and character creates dramatic irony. In a Reverse Ghost Ship Moment, when that gap in information is exploited or subverted, it can have a jarring effect on the audience. Done correctly, it can be powerful, as anyone who’s seen the first season of Game of Thrones can attest. Done incorrectly (as most of the above examples show), it can alienate and confuse the audience.

Ben Adams is a Naval Officer living in Southern California who should probably be using his time more effectively. When he’s not driving warships or fighting pirates, he maintains a blog.